On the road while making Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rain People during the days and evenings of fall 1968, production assistant George Lucas was also rising before dawn to work on his first feature film, THX 1138.

“George was writing the script,” recalls Mona Skager, script supervisor on Coppola’s movie. “He would write and I would type it up.” During postproduction, while sitting with some of the crew in a dingy room, Lucas once spoke about another film he wanted to make. “We were all waiting in a motel room for Francis to come,” Skager says, “and George was watching television—when all of a sudden he started talking about holograms, spaceships, and the wave of the future. Quite frankly, I didn’t even know what a hologram was, but he had a vision of doing some kind of science-fiction film.”

Skager is thus the first on record, but hardly the last, to be perplexed by Lucas’s genre-bending ideas. Only a few years before, he had been a student in the University of Southern California’s School of Cinema, making visual tone poems and abstract shorts with a professionalism that wowed his contemporaries; his last project had been THX 1138.4EB. Recipient of the Samuel Warner Memorial Scholarship, Lucas met Coppola on the Warner Bros. lot, where the slightly older UCLA film school graduate was making Finian’s Rainbow. The two hit it off, with Coppola encouraging Lucas to write and make movies. Up until this time Lucas had figured he would work in the avant-garde documentary and animation fields. Instead, by 1968 he was scribbling out the plot and words for a feature-length version of his last student film while already contemplating a more fantastic, cinematic variation on a theme.

“I had thought about doing what became Star Wars long before THX 1138,” Lucas says. “I’ve always been intrigued with Flash Gordon. It was one of my favorite serials and comic books, along with Tommy Tomorrow and those kinds of things. I really loved adventures in outer space, and I wanted to do something in that genre, which is where THX partially came from. THX really is Buck Rogers in the twentieth century, rather than Buck Rogers in the future.”

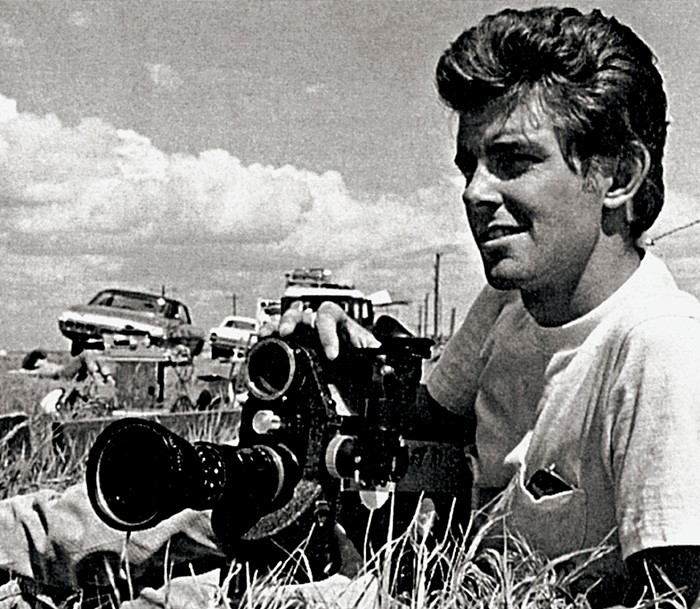

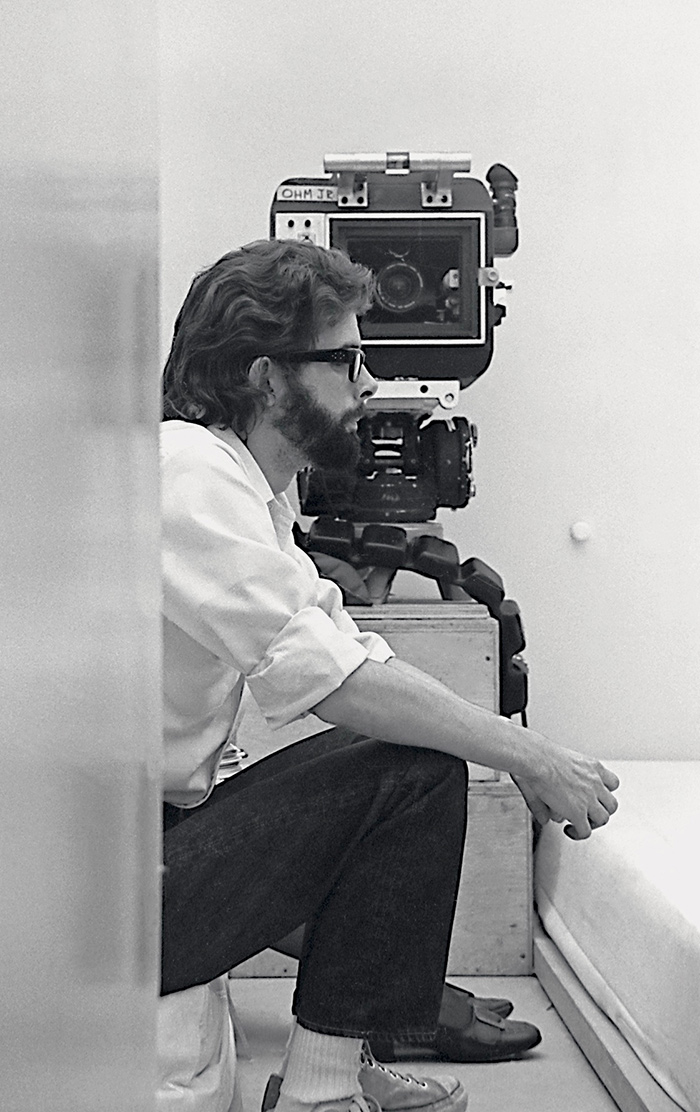

Lucas with camera, circa 1966.

The young filmmaker at work on the documentary short subject 6.18.67 (1967)–a poetic look at the making of Mackenna’s Gold, a Western starring Gregory Peck.

Executive producer and writer George Lucas discusses how his changing perspectives

on the Flash Gordon serials sparked his desire to make the Star Wars saga. (Interview

by Arnold, 1979)

(1:50)

In 1969, following the release of The Rain People, Coppola and Lucas founded American Zoetrope, an independent film company, on Folsom Street in San Francisco. THX 1138 became its first film. “When I met Francis and started working as his assistant, because he is very much the writer, he really started pushing me toward theatrical drama, acting—and writing,” Lucas says. “He had to force me to write my first script. ‘You want to do a film? You write it.’ And I said, ‘No, no, no, we ought to hire a writer to write it. I don’t want to write it. I’m not a writer, I can’t write.’ But he said, ‘You’re never going to be a good director unless you learn how to write. Go and write, kid.’

“So I turned out my first script, THX, and it was terrible,” Lucas continues. “I said, ‘See! It’s terrible. Let’s hire a writer.’ So he hired a writer—but that experience was worse than writing it myself. I may be a terrible writer, but at least I know what I want to say. So I went back and rewrote it with a friend of mine, Walter Murch, and it turned out being what it is.”

Those familiar with the story of American Zoetrope know that what THX 1138 was led to Black Thursday—the day which destroyed the fledgling company in its first incarnation and that could’ve permanently exiled both Coppola and Lucas from the industry.

On Thursday, November 19, 1970, in a screening room on the Warner Bros. lot, the lights went down and THX 1138 was screened for the executives who had bankrolled the film to the tune of $777,777.77 (a tribute to Coppola’s lucky number). After the lights came back up, it quickly became clear that Warner Bros. didn’t understand the film, didn’t like it, and certainly didn’t have a clue as to how they were going to market it. Lucas had anticipated their reaction, and had even planned with his friends to escape with the negative should the executives try to seize it—and they did. Ultimately, Warner Bros. exercised its corporate mind-set by cutting the film by five minutes without really changing or improving anything, though they did succeed in completely alienating the film’s director. They released THX 1138 on March 11, 1971, without knowing what they were selling.

Though it found a small audience and some favorable reviews, the film was no Easy Rider at the box office. The film’s tepid reception and its disastrous screening prompted Warner Bros. to withdraw funding from American Zoetrope; they also asked Coppola to pay back the $300,000 previously loaned for the development of six other films slated for production, among them Apocalypse Now, The Conversation, and The Black Stallion. Lucas’s first film couldn’t have been more disappointing from a commercial point of view—and would have aborted the career of a lesser talent. Personally, however, Lucas was happy with THX 1138, with its humor, its stylized visuals, its documentary-style storytelling, and its tale of an individual who steps outside his mental cage to a more liberated existence. Despite the fact that the creation of THX 1138 left Lucas unemployed and penniless, it led to many positives—and, eventually, to Star Wars.

Lucas and driver Tony Dingman, while making Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rain People in 1968.

Coppola gets a ride astride the vehicles of two motorcycle cops.

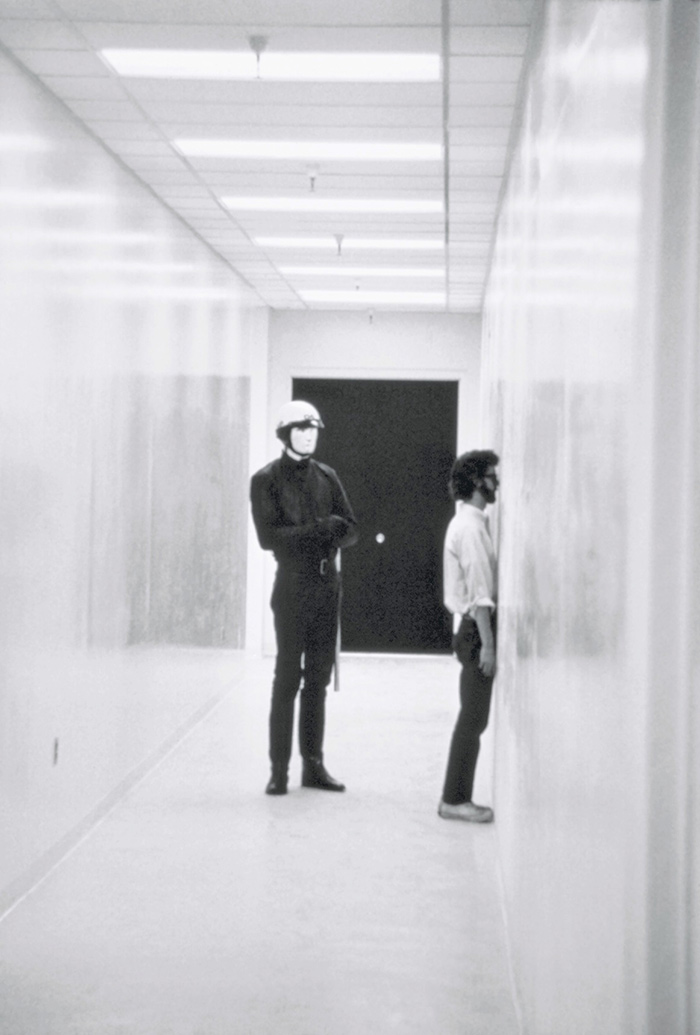

While directing his first feature film, THX 1138, in 1969, Lucas shows one of the robot police how to stand.

Lucas explains how he decided to go to film school at the University of Southern California.

(Interview by Alan Arnold, 1979)

(2:43)

While Lucas was at work on THX 1138, Coppola had delivered a second challenge: to make a happier kind of film. The young director took up the gauntlet, deciding to make a movie about his youth in Modesto, California, where teenagers cruised in beautiful hot rods and listened to great music while looking for girls and growing up. The film would be called American Graffiti, a wink to this vanished pastime. However, Coppola’s first challenge—writing—was not something Lucas was eager to face again.

“When I was in college I took a creative writing class,” Lucas says, “but I really didn’t like it. My real thing was art, drawing, visuals. When I went to USC, my primary interest was camera and editing. That was what I really excelled in, so that was what I really liked. I was bored by scripts, and most of the films I did were abstract visual tone poems or documentaries—those were the things I really loved.

“So as I started out with American Graffiti, I said to myself, I don’t want to write this; I can’t stand writing, and I frantically went around trying to get a deal to develop the script.”

His hope was that his friends Willard and Gloria Huyck (the Huycks) would write the script once he had funds to pay them. To raise the development money, Lucas spent more than six months chasing down possibilities, talking with lower- and upper-level studio executives, such as David Chasman, head of development at United Artists in Los Angeles. But he, like everyone else, declined, much to the frustration of an increasingly destitute Lucas.

Having heard that THX 1138 had been chosen as one of the films to be featured in the Directors’ Fortnight at the International Film Festival in Cannes, Lucas and his wife, Marcia, decided to spend their last few dollars on a vacation in Europe during the month of May 1971 (among the other films featured that year were Alain Tanner’s La Salamandre and Volker Schlondorff’s The Sudden Wealth of the Poor People of Kombach). At the time Walter Murch happened to be going with his wife, Aggie, to visit her mother in England. “I said, ‘If you’re going over there, we’ll come, too—I’ve never been to Europe. I’ll just get a backpack,’ ” remembers Lucas.

On the way he and Marcia stopped for about a week in New York City, where they stayed with Coppola, who was on location shooting The Godfather, partially to repay his debt to Warner Bros. While in Manhattan, Lucas took the opportunity to explore deal possibilities. Even though Chasman had turned him down, he was able to talk “directly” with David Picker, president of United Artists, about his ideas for Graffiti. “Picker said, ‘Let me think about this. When are you leaving?’ I said in a couple of days, on my birthday [May 14]. So he said, ‘Why don’t you call me at Cannes when you get to London, and I’ll let you know.’ ”

On a previous visit with Coppola to New York, Lucas had checked out one avenue for his fantasy-space adventure. “I tried to buy the rights to Flash Gordon,” Lucas recalls. “I’d been toying with the idea, and that’s when I went, on a whim, to King Features. But I couldn’t get the rights to it. They said they wanted Federico Fellini to direct it, and they wanted 80 percent of the gross, so I said forget it. I could never make any kind of studio deal with that.”

But King Features’ brush-off was key in the crystallization of Lucas’s thinking—at that moment, his project went from being a licensed product to an original screenplay. “I realized that Flash Gordon is like anything you do that is established,” he says. “That is, you start out being faithful to the original material, but eventually it gets in the way of the creativity. I realized that Flash Gordon wasn’t the movie I wanted to do; if I had done it, I would’ve had to have Ming the Merciless in it—and I didn’t want to have Ming the Merciless. I decided at that point to do something more original. I knew I could do something totally new. I wanted to take ancient mythological motifs and update them—I wanted to have something totally free and fun, the way I remembered space fantasy.”

Those memories, of course, hark back to Lucas’s 1950s childhood in Modesto, California. In what was then a rural town he, like millions of other children, had been able to dream along with the fantastic imagery of the tail end of the golden age of comic books and cinema. Artists such as Alex Raymond, Al Williamson, and Frank Frazetta illustrated fabulous worlds of the future and the past, while many of the swashbuckling films and 1930s serials were being broadcast on television for the first time.

Lucas and Coppola in discussion at a restaurant, circa 1970.

Back with Francis and his wife, Eleanor, in their apartment, Lucas and Coppola no doubt compared notes on their prospective futures, neither of which looked too bright. “Francis was in the middle of severe trauma at the time, and Ellie was pregnant,” Lucas says. “We had to leave at around 7 AM to catch the plane to London—but Francis and Ellie got up at four in the morning, running through the room on their way to the hospital, because she was in labor. She had Sofia that day. When we got to London and our tiny pension, because we were doing Europe literally on $5 a day, I found a pay phone and called David Picker, who said, ‘I’ve thought about this and you can have some money and you can write it. I’m going to be at the Carlton. Come and visit me there and we’ll talk about it.’ So it was my birthday, it was Sofia’s birthday, and I got American Graffiti all on the same day.”

The “money” was $5,000 to develop the script, $5,000 upon delivery, and $15,000 more in the event the movie was actually made. “I immediately called the Huycks and said, ‘I got the deal. We can write the script.’ But they said, ‘Oh, gee, George, we just got a chance to direct our own movie.’ So I said, ‘Okay, look, that’s a great opportunity; I’ll think of something else.’ ”

Using his Eurailpass, Lucas took the train to Cannes, where he met up with Murch, who had bicycled there from England. Sticking to their budget, they stayed in a “beautiful” little hotel far off the beaten path in the hills above the town. “We even had to sneak in to see THX because we didn’t have tickets,” Lucas says. “There was also a press conference that we didn’t go to, because nobody told us about it. But then I got to visit David Picker at the Carlton Hotel in one of those big suites—that was my first big-time movie experience. Before, I’d only been let into underling executive offices.”

After confirming the details of the Graffiti deal, Picker asked Lucas if he had anything else that might interest United Artists. “I said, ‘Well, I’ve been toying with this idea of a space-opera fantasy film in the vein of Flash Gordon,’ ” Lucas says. “And he said, ‘Great, we’ll make a deal for that, too.’ And that was really the birth of Star Wars. It was only a notion up to then—at that point, it became an obligation [laughs]!”

Lucas didn’t mention to Picker another film he’d been struggling to make for several years, Apocalypse Now, because it had already been turned down by United Artists, after having been rejected by Warner Bros. Born from the tumults of the 1960s, it existed as a script he’d worked on with John Milius and was going to be “Dr. Strangelove in Vietnam,” according to Lucas, filmed in documentary style with handheld 16mm cameras.

“I knew I could barely get off the ground a $500,000 cheap exploitation hot-rods-to-hell movie,” Lucas explains, “so I figured, well at least I’ll get that done. I’d continue to develop Apocalypse Now—it was all ready—but Graffiti would be cheap, it was quick, and I thought it was really commercial.”

After traveling from the south of France to Italy, Lucas made another telephone call to the States—this time from Rome—to Gary Kurtz to discuss hiring Richard Walters to write Graffiti, since the Huycks were busy.

Years before, when Gary Kurtz had been drafted, he’d been one of the first conscientious objectors in the marines. Instead of being thrown into the brig, however, Kurtz had been assigned to the photographic unit. After serving his time, Kurtz worked with Coppola for the king of bargain-basement exploitation flicks, Roger Corman. Years later, when Coppola mentioned to Kurtz that Lucas was filming THX 1138 in Techniscope—a cheap, grainy, but sometimes appropriate anamorphic wide-screen format—Kurtz traveled to Marin County to meet the director and watch a reel of his film, because he was thinking of doing a movie using the same technique.

“Later I came back to San Francisco to get an idea of what the dubbing room was like for THX,” Kurtz says, “and at that time I talked with George at great length.”

Returning from Europe to the United States a few weeks later, Lucas had lunch with Kurtz in the commissary on the Universal lot, across the street from where Monte Hellman was cutting his film Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), which Kurtz was line-producing. Kurtz had been hired in the same capacity by Coppola for Apocalypse Now, which he was producing, but because that film was stalled Kurtz segued into the same position on American Graffiti. Lucas spent the summer of 1971 and most of the following year working on the Graffiti screenplay, first with Richard Walters, then by himself.

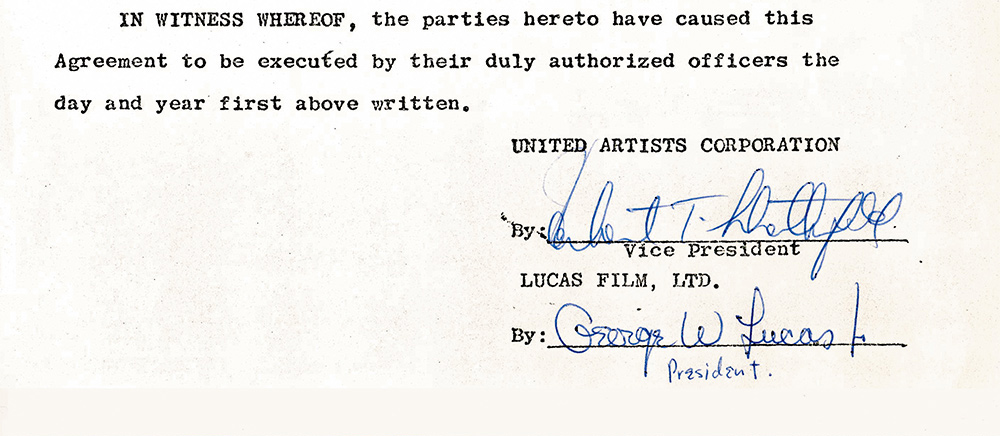

George W. (Walton) Lucas Jr.’s signature on his agreement with the United Artists Corporation to write the script for American Graffiti and to eventually develop “a second picture.”

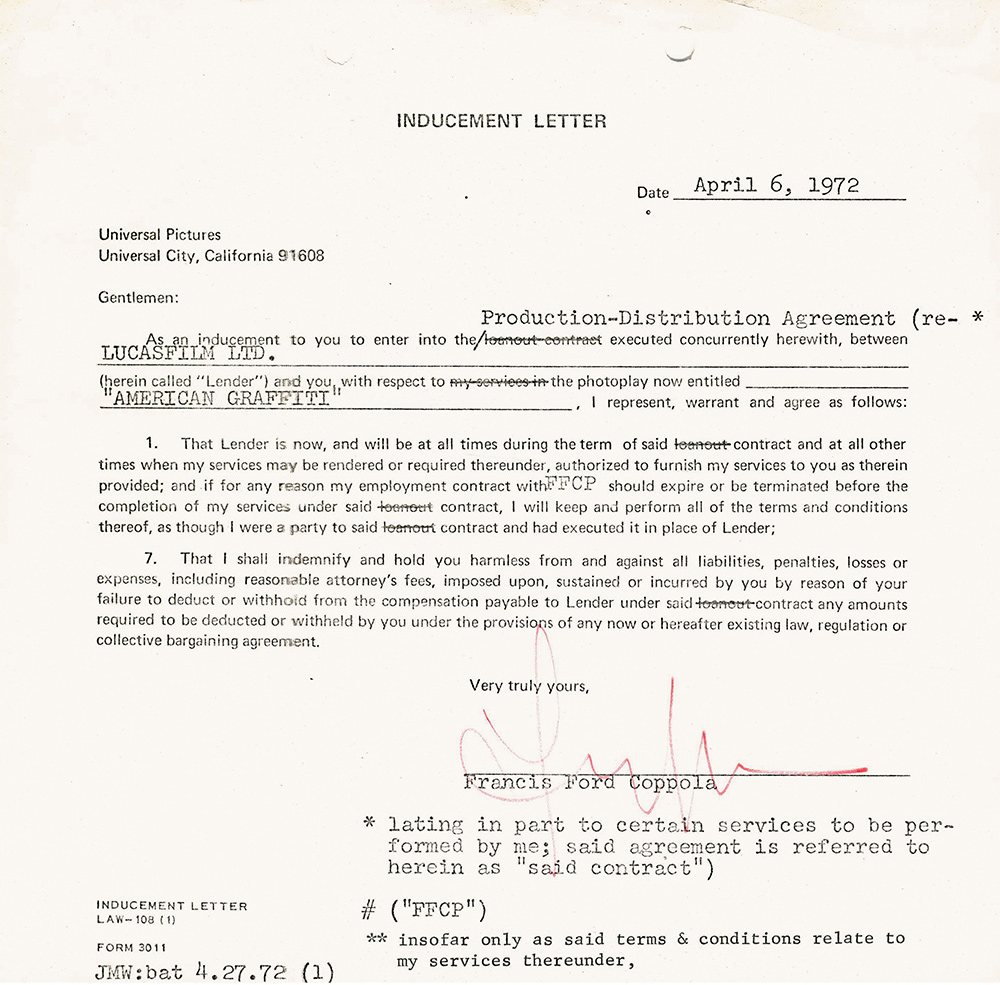

Francis Ford Coppola’s signature on Universal Pictures’ “Inducement Letter,” which enabled Lucas to make American Graffiti after United Artists passed on it, and which gave Universal an option on the “second picture.”

On December 28, 1971, the financing agreement between Lucasfilm and United Artists for the development of two films—American Graffiti and “a second picture”—was made legal. Oddly, even though United Artists had registered the title “The Star Wars” with the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) on August 3, 1971, it is not named as such in the agreement (perhaps because the studio’s contract department wasn’t talking with whatever department was responsible for the trademarking of titles).

Representing Lucas in the negotiations was the law office of Tom Pollock, Jake Bloom, and Andy Rigrod, which had helped the writer-director incorporate his own company, Lucasfilm, earlier that year. The trio had met years earlier during weekly poker games. They joined forces in 1970, eventually evolving their practice into one specializing in the entertainment field, with Rigrod handling contracts, Pollock studio negotiations, and Bloom merchandising—three areas that would be crucial for Lucas in the years to come.

“I worked as the lawyer for the American Film Institute for three years, as their business manager and putting together their new film school,” Pollock says. “Many of my first clients were the filmmakers that I met there. Among them were two young writers named Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood, and they had a friend who needed a lawyer, who was just in the process of making his first feature film, THX 1138. So they introduced me to George, and that’s how we started our relationship.”

Barwood, Robbins, and Lucas had met at USC. The former two had gone on to become filmmakers in their own right, and they all kept in touch. After collaborating with Lucas on the script for his student film, Robbins had even doubled for Robert Duvall when the actor was unavailable for the last shot of THX against the setting sun. Through Coppola, Lucas met Jeff Berg, who had seen THX 1138 and been impressed. Berg became Lucas’s agent—last of the key players brought to Lucas via his first film. The help of all parties was going to be needed to get Graffiti going, despite Picker’s initial enthusiasm.

“I ended up writing Graffiti, and it wasn’t that bad,” Lucas says. “But UA read the script and said, ‘No, it’s not our movie.’ So that meant another six months of taking it all over town trying to get it sold.”

By this time, however, Coppola had recovered from his consecutive traumas. The Godfather had been released in March 1972 to critical and box-office mega-success, reversing the director’s fortunes and elevating his deal-making clout to that of the divine. “Finally, Universal said they’d do Graffiti if I could get somebody like Francis involved,” Lucas says. “So I brought Francis in as the producer.”

The deal was for three pictures: American Graffiti and two future films. The “Lucas Option Contract” and “Inducement Letter” were signed on April 6, 1972. In addition to spelling out that American Graffiti’s production budget was not to exceed $775,000—even less than that of THX—it also stipulated that the two other pictures automatically had priority over any other projects Lucas might develop in the future.

“We were on our way,” Lucas says. “I was starting to get into production, but I still felt the script needed work. By this time the Huycks had finished their movie, so I said, ‘Look, I’m going to start shooting in eight weeks, come and work on my script.’ ” Not really doing a rewrite, the Huycks worked primarily on the dialogue and the relationship between Steve and Laurie, two of the film’s teenage protagonists.

Principal photography for Graffiti began on June 26 and wrapped on August 4, a twenty-nine-day schedule. It was a quick, grueling night shoot, with Lucas directing, Coppola producing, and Kurtz as the line producer/production manager. Harrison Ford, who plays Bob Falfa in the film, recalls his meetings with Kurtz: “He was the guy who told me no more drinking beer on the streets, and then no more drinking beer in the trailer, and then no more drinking beer. Those were my three basic contacts with him. He explained it was a matter of insurance. He was real nervous.”

In November 1972, while Lucas was in postproduction on Graffiti, he sent Kurtz to scout locations in the Philippines and Hong Kong for what he hoped would be his next film, Apocalypse Now. Kurtz stayed on the road until Christmas. Columbia Pictures was showing renewed interest in the film, and Lucas, who had wanted to make Apocalypse Now after THX 1138, was even more intent on not being put off a second time.

Alas, after Lucas had turned over Graffiti to Universal in early 1973, but half a year before its release, Columbia dropped Apocalypse Now. Lucas doggedly took it to several other studios, but no one wanted it. The Vietnam War was just too controversial. Lucas was in a fix: He was desperately poor—and Universal, like United Artists before it, was confused by and pessimistic about the prospects of American Graffiti. It told several stories that were intercut, which was revolutionary at the time, and it didn’t seem to have a plot. Despite a particularly enthusiastic preview, Universal began toying with the idea of releasing it on television instead of in theaters.

It was at that moment of despair that Lucas turned back to the “unnamed science-fiction project”—because at least it had the remnants of interest back at United Artists, where he’d signed the original development deal.

“I was in debt,” Lucas says. “I needed a job very badly, and I didn’t know what was going to happen with Graffiti, so I started to work on Star Wars rather than continue with Apocalypse Now. I had worked on Apocalypse Now for about four years and I had very strong feelings about it. I wanted to do it, but could not get it off the ground. Columbia had just turned it down. It had started at Warner and then it went to Paramount, and it had been just about everywhere in town. Everybody had that script at least once, and the main studios had had it twice. I think everybody was just afraid of the Vietnam War and they were afraid that it was going to cost more than what we thought it was going to cost, and nobody wanted to go near it. So I figured what the heck, I’ve got to do something, I’ll start developing Star Wars.”

Throughout his life up to that point, Lucas had had a number of key interests, apart from cinema and art: anthropology—the interaction of politics, history, and people; mythology, as a representation of cultural conditioning; traditional adventure stories; and … speed. From hot rods to rocket ships. All three interests are present in THX 1138, which contains an ambiguous government, robot police, a judicial system ruled by a computer, and people who are persecuted for not taking drugs prescribed by the state; it opens with a clip from a Buck Rogers serial and ends with an ultra-high-speed car and motorcycle chase. Graffiti also ends with a high-speed vehicular climax and a coda that mentions the Vietnam War—in fact, the whole film takes place within the shadow of that conflict and the impending social upheaval of the 1960s. But with Apocalypse Now on the sidelines, many of its particular political conceits were transferred to the front lines of Lucas’s space-fantasy film.

“A lot of my interest in Apocalypse Now was carried over into Star Wars,” Lucas says. “I figured that I couldn’t make that film because it was about the Vietnam War, so I would essentially deal with some of the same interesting concepts that I was going to use and convert them into space fantasy, so you’d have essentially a large technological empire going after a small group of freedom fighters or human beings.”

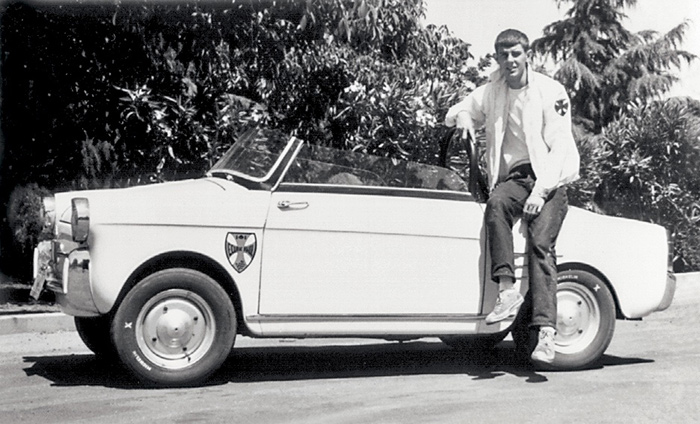

Lucas’s love of fast machines began with his own Fiat Bianchina.

It made the jump to cinema with THX, who roars away in a stolen Lola T70.

It continued with the ethereal glow of John Milner’s yellow hot rod cruising among other gleaming machines in American Graffiti.

“I grew up working on hot cars and I like hot cars,” Lucas says. “It’s something that I am personally drawn toward. Even before I was a teenager, I always wanted a hot car; when I got to be a teenager, I had a hot car and I worked on hot cars. That was my big drive in life—until I got into films. So it’s carried over into film.”

As George Lucas began to write, he moved in his mind from the large to the small, from big themes—such as those inherent in his thinking on conflict, governments, and Vietnam—to details, such as the names of characters and planets. He made lists that often read like streams of consciousness. Perhaps his first writing germane to Star Wars is a roster that dates from early 1973; the name at the top of the page is “Emperor Ford Xerxes XII” (Xerxes was a Persian king assassinated by one of his sons), followed by: “Xenos, Thorpe, Roland, Monroe, Lars, Kane, Hayden, Crispin, Leila, Zena, Owen, Mace, Wan, Star, Bail, Biggs, Bligh, Cain, Clegg, Fleet, Valorum.”

Not long afterward, Lucas started combining first and last names, and assigned roles to them. Alexander Xerxes XII becomes “Emperor of Decarte.” Owen Lars is an “Imperial General”; Han Solo is “leader of the Hubble people” (probably named for Edwin Hubble, the astronomer); Mace Windy is a “Jedi-Bendu”; C.2. Thorpe is a space pilot; Lord Annakin Starkiller is “King of Bebers”; and Luke Skywalker is “Prince of Bebers.”

Lucas used the same process for his locales, listing names, then giving them characteristics. “Yoshiro” and “Aquilae” are desert planets; “Brunhuld” and then “Alderaan” are city planets, capital of the “Border System.” Others listed are: “Anchorhead, Bestine, Starbuck, Lundee, Yavin, Kissel, Herald Square.” Aquilae is where the Hubble and Beber people live; Yavin becomes a jungle planet, whose natives are eight-foot-tall Wookies; Ophuchi is a gaseous cloud planet where lovely women can be found; Norton II is an ice planet; and a “Station Complex” is noted among the space cruisers.

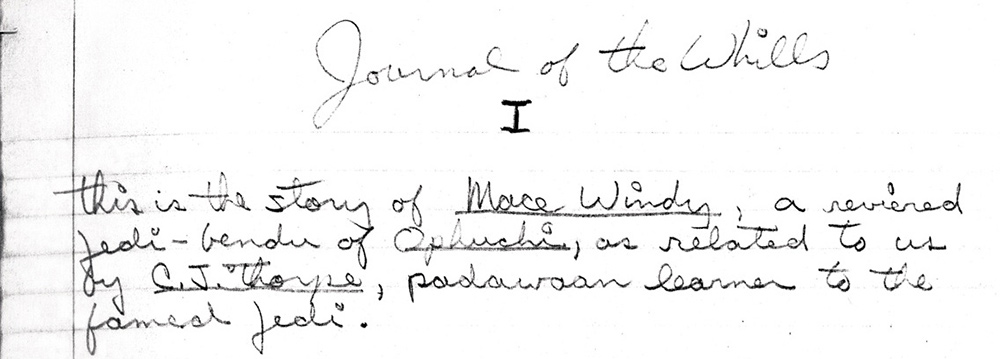

From these lists Lucas moved on to a handwritten two-page idea fragment titled Journal of the Whills, [Part] I, which recounts “the story of Mace Windy, a revered Jedi-Bendu of Ophuchi, as related to us by C. J. Thorpe, padawaan learner to the famed Jedi.”

The initials C.J. or C.2. (it switches back and forth) stand for “Chuiee Two Thorpe of Kissel. My father is Han Dardell Thorpe, chief pilot of the renown galactic cruiser Tarnack.” At the age of sixteen Chuiee enters the “exalted Intersystems Academy to train as a potential Jedi-Templer. It is here that I became padawaan learner to the great Mace Windy … at that time, Warlord to the Chairman of the Alliance of Independent Systems … Some felt he was even more powerful than the Imperial leader of the Galactic Empire … Ironically, it was his own comrades’ fear … that led to his replacement … and expulsion from the royal forces.”

After Windy’s dismissal, Chuiee begs to stay in his service “until I had finished my education.” Part II takes up the story: “It was four years later that our greatest adventure began. We were guardians on a shipment of fusion portables to Yavin, when we were summoned to the desolate second planet of Yoshiro by a mysterious courier from the Chairman of the Alliance.” At this point Lucas’s first space-fantasy narrative trails off…

Handwritten first page of Lucas’s Journal of the Whills.

Although light-years from what was to come, the two-page Journal has a number of elements that Lucas would recycle into subsequent drafts: the Jedi; the phonetics of Chuiee; a great pilot named Han; an academy; and the galactic Empire. “Journal of the Whills came from the fact that you ‘will’ things to happen,” Lucas says. Much like the Disney films that opened and closed with the device of a storybook, “the introduction was meant to emphasize that whatever story followed came from a book.”

No notes bear witness to the transition of Lucas’s thinking from this fragment to his next effort, but he probably did what he would do again and again when creatively stuck: He started making new lists, with new plot points, before writing another tale. This time the plot points were hard coming—until he remembered a particular Akira Kurosawa movie he’d seen. Lucas had already been leaning in that direction, as the name Yoshiro in the Journal is a variation on Toshiro, the first name of the great Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune, who starred in many of Kurosawa’s films, including Yojimbo (1961).

Lucas’s ten-page handwritten treatment, titled “The Star Wars” and dated May 1973, relies for its structure on another Kurosawa classic, Kakushi-toride no san-akunin (The Hidden Fortress, 1958). Lucas had first encountered the work of the great Japanese director at USC, where he was impressed with Shichinin no samurai (Seven Samurai, 1954). Not only was its master-disciple relationship of interest to the young student, but Lucas also admired Kurosawa’s fast edits.

“Hidden Fortress was an influence on Star Wars right from the very beginning,” Lucas says. “I was searching around for a story. I had some scenes—the cantina scene and the space battle scene—but I couldn’t think of a basic plot. Originally, the film was a good concept in search of a story. And then I thought of Hidden Fortress, which I’d seen again in 1972 or ’73, and so the first plots were very much like it.”

In Kurosawa’s black-and-white masterpiece, two bickering peasants become entangled with a princess and a general (Mifune) who are hiding out during a civil war, and end up helping their social superiors in their adventures. Certain scenes in Lucas’s treatment are reminiscent of Hidden Fortress, notably where General Skywalker can’t check his bird-steed in time and barrels into the camp of his enemies, much like Kurosawa’s general who can’t check his horse and gallops into a hostile camp. Skywalker’s one noted mannerism—he scratches his head—is taken from Mifune’s performance in several of Kurosawa’s films. “Having the two bureaucrats or peasants is really like having two clowns—it goes back to Shakespeare,” Lucas says, “which is probably where Kurosawa got it.”

Lucas on the set of THX 1138.

John Ford’s 1956 film The Searchers was also an early influence. Its saloon scene partially inspired the treatment’s cantina sequence. All in all Lucas’s exotic creatures and aliens, space battles and bird-steeds come from a mind formed by the reading and viewing habits of a typical 1950s kid—but these influences were just beginning a long transformation. One can already see how the “lost” boys of Peter Pan have become, given the political sway of the writer’s mind, jungle rebels with just a hint of the Vietcong. Lucas’s idiosyncratic mental amalgam would continue to reformulate ideas and materials—while Lucas the deal maker would try to procure the necessary funds to create a cinematic venue for their expression.

Having decided to develop the quasi-science-fiction film sometime early in the spring of 1973, Lucas approached United Artists again, and according to Lucas’s agent Jeff Berg they talked about “an epic space fantasy.” On May 7, 1973, Berg met with David Chasman, who was now vice president of production under David Picker, and gave him the fourteen-page typed treatment. On behalf of his client, Berg asked for a $20,000 development fee to transform the treatment into a screenplay. To give United Artists an idea of what kind of visuals he had in mind, Lucas had attached ten images to the treatment: four NASA photos (astronauts in space, satellites, spaceships with peculiarly shaped flat wings); a photo of US Army amphibious tanks; and five fantasy illustrations, consisting of a skull-faced, muscular man holding a dead woman, pietà-like; a sci-fi fantasy hero, crouching and holding a blaster; a swarm of warriors fighting a giant furry creature; another sci-fi hero standing next to a futuristic vehicle; and a goggle-faced alien staring out at the viewer.

Once again it was the time of the year for the International Film Festival, so Berg wired Chasman at Cannes on May 14, 1973. “I wrote something like, ‘Hey, we’re waiting [for] word from you on the science-fiction project—do you want to proceed with it or not?’ ” Berg says, “but they wound up passing on it.” United Artists’ official negative response came on May 29, 1973. “United Artists passed on it, and money was the main reason as I recall,” Pollock adds. “We had told them from the beginning that it was going to cost $3 million. We wanted to go with UA, but we then had a contractual obligation to submit the project to Universal, because when they made Graffiti they made George sign a deal for two options.”

In June 1973, however, Lucas was not enamored of Universal. In its continuing incomprehension of American Graffiti, the studio—in an almost exact replay of Warner Bros.’ handling of THX 1138—had cut five minutes from the film. “We did not want to go with Universal,” Pollock says. “At the time George was very unhappy with them, during the months of April and May, when the studio was recutting the movie.”

Nevertheless, on May 30 or June 1, Lucas’s treatment was duly submitted to studio executive Ned Tannen. Under the terms of the agreement, Universal had ten days to say whether or not they were interested. “We sent them a letter saying, this is the movie we want to make, it’s going to cost $3 million. We want this fee, we want this percentage of the profits,” Pollock recalls. “The only official word we ever heard was Ned calling back asking for more time. He couldn’t make a decision in ten days. At the end of the ten-day period, we sent him a letter saying, ‘Since you haven’t said yes, the answer is no.’ ”

Later stories circulated that perhaps Tannen wanted it, but Lew Wasserman, the legendary éminence grise of Universal, had said, “We don’t make science-fiction movies.” Pollock’s recollection, however, is that “Ned was in a waffling state because he was in a waffling state about American Graffiti at the time.”

“The question becomes, Did Universal screw up and let the letter go unnoticed—were they derelict in some kind of procedural area?” Berg says. “The answer is no—Universal works like clockwork. They never screw up in that area. They have the most efficient notification follow-up department of any studio in town. They didn’t proceed with the project because either they didn’t believe in the idea, or they were not comfortable with George making a picture of that size, $3 million, which in 1973 was still regarded as an expensive picture. It was before the advent of the $8 to $10 million movies. Although Universal has a history of making expensive pictures, George had always presented himself as an underground, independent filmmaker. Psychologically, they weren’t prepared.”

Although this last rejection probably didn’t hurt Lucas, the consistently pedestrian behavior of the studios almost certainly sharpened his distaste for Hollywood. “UA was very cool,” Lucas says. “I just think they thought of it as a big, expensive movie and they didn’t understand it. Universal was the same way.” Maybe dreaming of a more ideal studio, Lucas adds, “I think Disney would have accepted this movie if Walt Disney were still alive. Walt Disney not only had vision, but he was also an extremely adventurous person. He wasn’t afraid.”

While Universal was still scratching its corporate head over The Star Wars, Jeff Berg had already started informal discussions with vice president for creative affairs Alan Ladd Jr. at Twentieth Century-Fox, which is located in Century City, Los Angeles, just west of Beverly Hills. “I’d been talking to Laddie about George Lucas. This was before American Graffiti came out, but Laddie had heard sensational things about it,” Berg says.

Son of the well-known actor Alan Ladd (The Blue Dahlia, 1946; Shane, 1953), Alan Ladd Jr. had been recruited by Jere Henshaw only months before, in January. The result of a merger in 1935 between Fox Film Corporation and Twentieth Century Pictures, the studio in 1973 was operating under the presidency of Gordon Stulberg and the chairmanship of Dennis Stanfill. One of the old-guard Hollywood juggernauts, the studio’s last few years had been rocky under the fading direction of longtime head Darryl Zanuck, who had finally left the company in 1971. According to Warren Hellman, who became one of the eleven directors on the board a few months later, the sole source of viable income in June 1973 was the television show M*A*S*H, which had started airing in 1972.

“Essentially Fox was going broke,” Hellman says. “We were in violation of all the important bank covenants. We were in intense negotiations with Chase, who was the leading bank, and who was being very harsh on us.”

New management was therefore looking for new ways to make hits, and the nearly incomprehensible Sean Connery vehicle Zardoz (1974) was Ladd’s first project.

“I was having drinks one day with Jeff Berg, who was talking about what a fabulous picture Graffiti was,” Alan Ladd Jr. says. “Universal was very unhappy with the picture, but Jeff thought it was a terrific film, so I said that I’d love to see it. Universal didn’t want it off the lot, but I was able to arrange a screening. I saw it on the Fox lot at nine one morning—and it absolutely bowled me over. That’s when I just said to Jeff that I’d like to meet George and hear about what ideas he’s working on.”

Berg arranged the meeting after making sure that Ladd understood that Universal still had right of first refusal. “George said he had this idea about Star Wars,” Ladd continues, “so I said, let’s make the deal. Having met George, I felt that Graffiti was further from what he was really into than Star Wars.”

Moreover, at Fox, the science-fiction genre was currently hot. Their sequels to Planet of the Apes (1968) had been good business. The fifth and last film in the series, Battle for the Planet of the Apes, had just opened on June 15, 1973—and the “furry alien” in Lucas’s treatment may have sparked dreams of a similar franchise. “When the Planet of the Apes series did so well for Fox, it’s possible that people’s interest was rejuvenated,” Kurtz says. “I’m sure there were people there who felt that there were other things that could be done in science fiction that also would make money.”

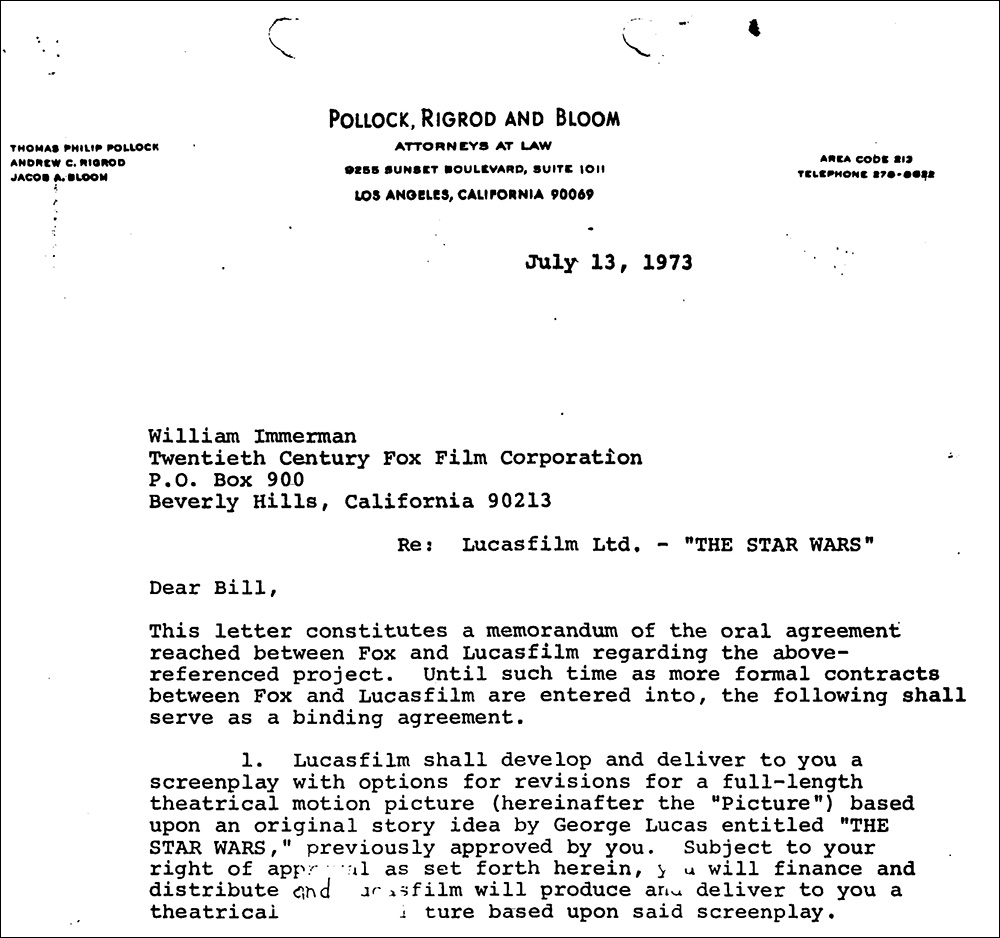

With Ladd’s interest assured and Universal officially out of the picture, Tom Pollock sent Twentieth Century-Fox a letter on July 13, 1973, outlining the same terms they’d proposed to Universal. “It was a very lowball deal,” he says, “with $15,000 for the development, $50,000 to write the script, and $100,000 to direct, some of which was even pledged to the completion of the movie. A $3 million budget and that’s it. We had no negotiating power. They were the only ones that wanted it.”

Pollock’s letter to vice president of business affairs William Immerman also stipulated that the first-draft screenplay would be written by October 31; that Lucasfilm could hire a secretary at $175 per week; that Gary Kurtz would produce for $50,000; and that Marcia Lucas and Verna Fields were “preapproved as editors and Walter Murch is preapproved as postproduction supervisor”—a logical clause given that they’d all worked well together on American Graffiti. Forty percent of the net profits of the picture would go to Lucasfilm, and 60 to Fox. Another clause addressed the issue of power: “[Twentieth Century-Fox] shall not have the right to assign an executive producer or exercise any other production controls other than standard location auditors.”

“I’m very, very adamant about my creative work,” Lucas says. “Even when I was young I was not that willing to even listen to other people’s ideas—I wanted everything to be my way. Over the years, starting in film school, I did start to work with others, because film is so collaborative, but I was still pretty closed-minded. I didn’t mind getting input from the creative people around me—but not the executives. I grew up in the 1960s. I was very anti-corporation, and I was here in San Francisco, where anti-authority is even more extreme. On my first two movies I was really left alone. No one watched dailies, no one really read the script. And when the studios interfered at the end, I thought it was the end of the world. It really wasn’t, but I felt it was. So I fought for many years to make sure no one could tell me what to do.

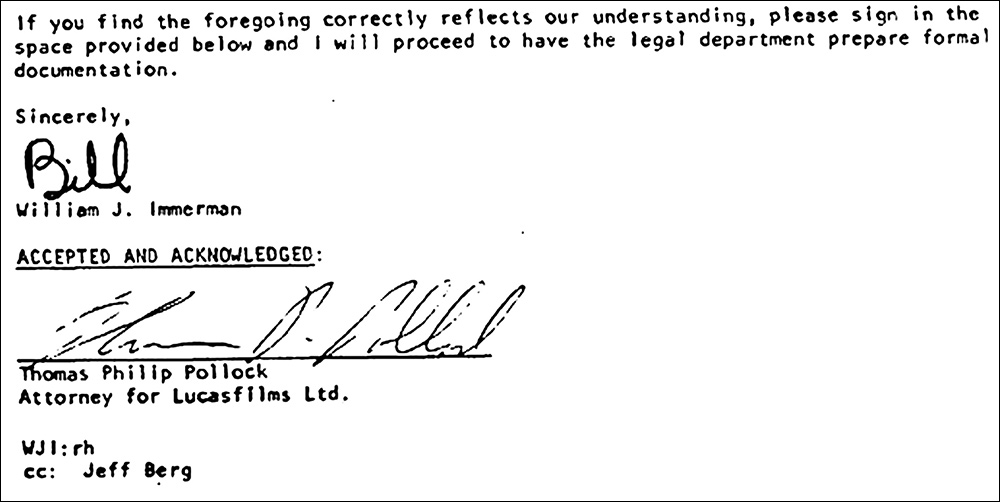

A letter of July 13 from the law offices of Pollock, Rigrod and Bloom became the basis for the deal memo between Lucas-film and Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation for The Star Wars.

As the legal representative of Lucasfilm, Thomas Pollock signed William J. Immerman’s return letter/deal memo of August 20, 1973, including it in his August 24 letter to Fox.

“I’m realistic enough to know that you have to make compromises when filmmaking,” he adds, “but if I can avoid them, I will.”

On August 20 Immerman sent back modifications to Pollock’s eight-page memo. On August 24 Pollock sent a letter with more amendments—including another preapproved Graffiti holdover, Fred Roos, as casting director—along with a note stating that United Artists had agreed to “waive its registration of the title [Star Wars] to any company designated by us.” The “Memorandum Agreement” between Twentieth Century-Fox and Lucasfilm Ltd. was signed retroactively on August 20—just nineteen days after Graffiti was released to surprisingly strong box office—but based on the pre-release July terms. The timing illustrates another motivating factor for Fox: Besides having faith in Lucas, Ladd, by acting fast, was able to sign up the promising director for very little.

“I actually needed the money in May because I was so far in debt,” Lucas says. “That’s why I made the deal. In September, by the time they sent me a check, Graffiti was already a big hit and I was okay financially. It’s ironic. If I’d just waited until Graffiti came out, I could have made the deal much better.”

A month after signing, Lucas received $10,000; he would receive another $10,000 “upon delivery of the first draft screenplay,” and $30,000 upon commencement of principal photography. The actual making of the film, however, was far—very far—from being assured at this point. The memo represented only an agreement to go to the next step; there was no formal production-distribution contract. The “Election to Proceed—Turnaround” clause made it clear that the studio could withdraw its financial support at any time “until Fox’s next Board of Directors meeting,” at which time they could “elect either to go forward with the project or not go forward with the project.” Lucas’s own commitment, as stated in an additional clause, was subject to his previous three-picture deal with Universal. If that studio elected to proceed with his film Radioland Murders, which Lucas had also been developing with the Huycks simultaneously with The Star Wars, then the former film would take priority.

Fox had simply decided to go ahead with the first phase: the development of the screenplay. They could read it and bow out, or go ahead with a revised draft and then bow out, which is the way any studio deal works.

“As with most companies that go through a lot of problems, the board had become quite obstreperous,” Warren Hellman says. “In theory Ladd reported to Stanfill, but he also had to bring his productions to the board—and it was always a moronic conversation. We were talking budgets and nobody knew anything about movies.” The one semi-exception was real-life princess Grace Kelly, a board member and former mega-star—but from the world of 1950s movies, which meant she had little grasp of the intricate mechanics of large-scale modernized filmmaking. Nevertheless, the board of directors gave Ladd permission to proceed with the first step.

While Berg notified Universal that Lucasfilm had accepted the deal at Fox under the same terms proposed earlier to them, Lucas attended a screening of American Graffiti at USC. A young man named Joe Viskocil was in the audience, and he remembers that “somebody asked George what his next project was, and he said ‘Star Wars’—and bells started ringing in my head because I realized that this was going to be a big show. I just felt it was going to be something really big.”