While the story of Star Wars was still just a few key scenes in his mind’s eye, Lucas’s completed film American Graffiti was released on August 1, 1973—but only after Lucas had arranged additional screenings and strategies to garner support for his movie, all of which ultimately persuaded Universal to finally book it into theaters. Probably to the studio’s great surprise, the seemingly disjointed film coalesced into one of the biggest moneymakers of all time—even more so in light of its profit-to-cost ratio, because the film was made for so little. For many kids, seeing Graffiti was a revelation: It was one of the first films to have humor that was for kids, while Lucas’s and Murch’s sound work made the music so alive that thousands of those same kids ran out and bought their first soundtrack ever. American Graffiti also sparked what has now become an American tradition of looking back on its immediate past—the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s—with fond recollections.

For Lucas the success of Graffiti meant many things, not least of which was the ability to pay off his many personal debts. He was also able to pay the mortgage on a home he’d bought in a burst of optimism just before the movie was released. Located in San Anselmo, a small town in Marin County (just north of San Francisco via the Golden Gate Bridge), it wasn’t far from a second building he purchased in January 1974—a one-story Victorian house originally built in 1869, which Lucas began remodeling as offices, with its dilapidated carriage house eventually transformed into editing rooms.

The success of the film also led to various obligations and ceremonies, all of which slowed the transformation of the Star Wars treatment into a rough draft. “When I was writing Star Wars, for the first year, there was an infinite number of distractions,” Lucas says. “Graffiti was a huge hit, plus I was restoring my office at the same time. Building a screening room kept me going for nine, ten months.”

Lucas did not hire a writer to work on The Star Wars, despite the myriad preoccupations. It hadn’t worked before, on THX and Graffiti, so there was no reason to try again. Instead, every day he’d walk up the stairs to his writing room at Medway—“it’s like a little tower”—and plug away on a desk he’d built from three doors. “I grew up in a middle-class Midwest-style American town with the corresponding work ethic,” Lucas explains. “So I sit at my desk for eight hours a day no matter what happens, even if I don’t write anything. It’s a terrible way to live. But I do it; I sit down and I do it. I can’t get out of my chair until five o’clock or five thirty or whenever the news comes on. It’s like being in school. It’s the only way I can force myself to write.

Lucas’s office in his former home in San Anselmo, as it appeared in 2006. Sitting at the desk he’d made from three doors (which is still there), Lucas could stare out of 180-degree wraparound windows while writing and suffering through the first drafts of The Star Wars.

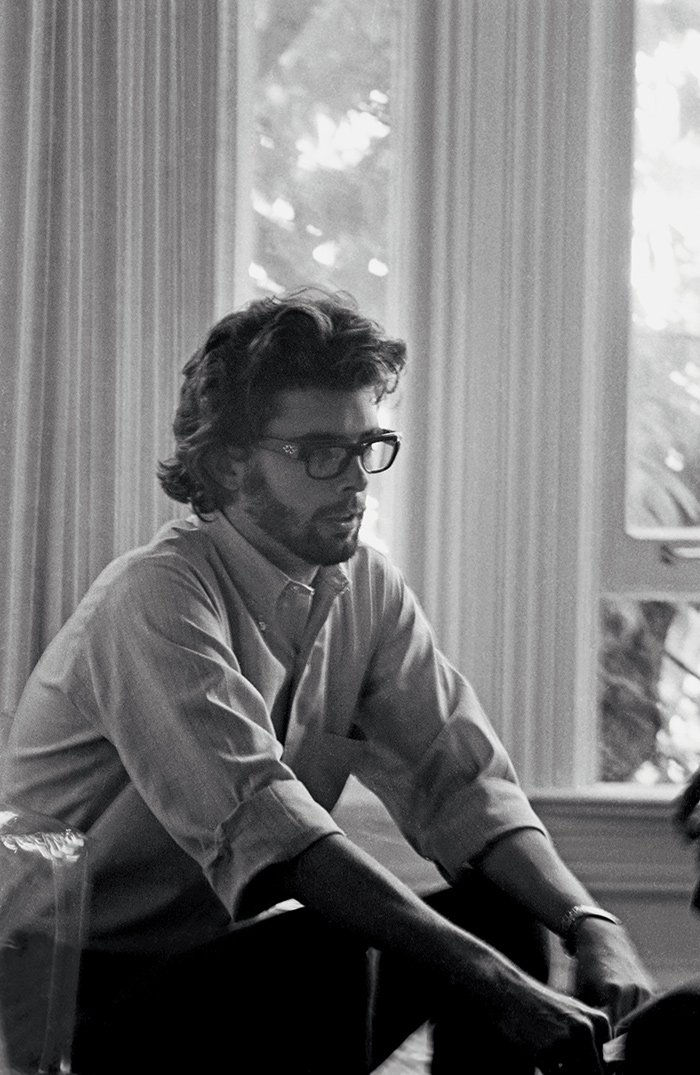

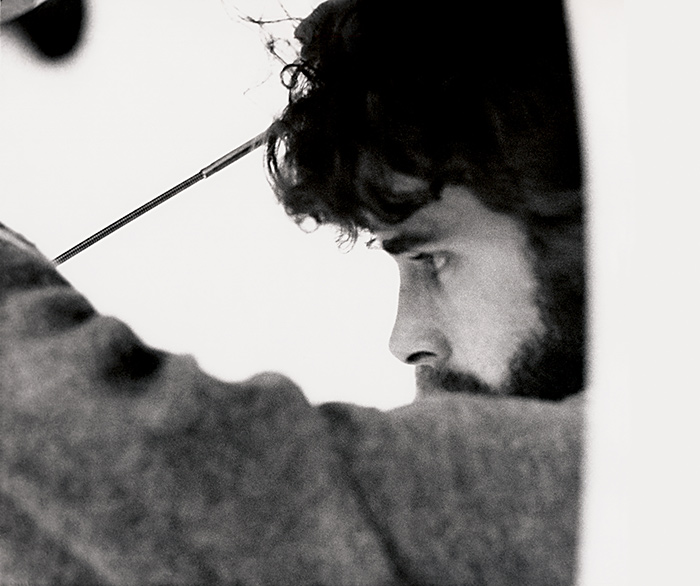

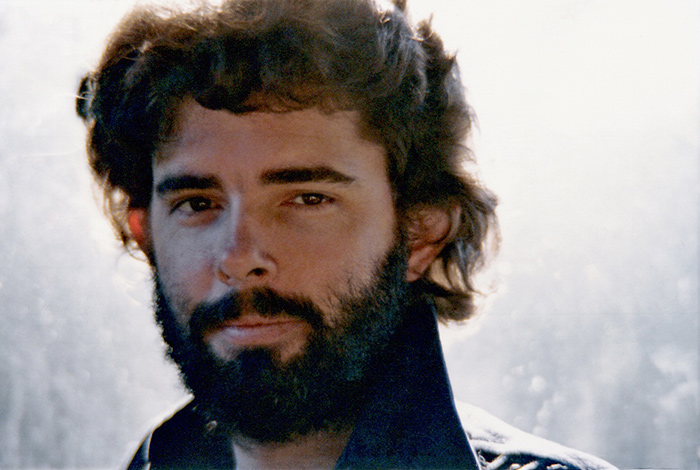

Lucas in the early 70s.

“I work with a hard pencil and regular lined paper,” he adds. “I put a big calendar on my wall. Tuesday I have to be on page twenty-five, Wednesday on page thirty, and so on. And every day I ‘X’ it off—I did those five pages. And if I do my five pages early, I get to quit. Never happens. I’ve always got about one page done by four o’clock in the afternoon, and during that next hour I usually write the rest. Sometimes I’ll get up early and write a lot of pages, but that doesn’t really happen much.”

Like most writers, even when not at his desk, Lucas was working. “A writer is, every waking hour, constantly pondering scenes or structural problems. I carry my little notebook around and I can always sit down and write. That’s the terrible part, because you can’t get away from it. I’ll lay in bed before I go to sleep, just thinking—or I’ll wake up in the middle of the night sometimes, thinking of things, and I’ll come up with ideas and I’ll write them down. Even when I’m driving, I come up with ideas. I come up with a lot of ideas when I’m taking a shower in the morning.”

Perhaps to celebrate the release of American Graffiti, Lucas sat down with a group of friends at a restaurant in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1973: (from left to right) Gary Kurtz, USC professor Ken Miura, Mona Skager, Bob Hall, Aggie and Walter Murch, filmmaker Michael Ritchie, Lucas, and Kurtz’s wife, Meredith.

Watching television also became part of the screenwriting process in the latter part of 1973, when Lucas began to collect real footage of flying planes in anticipation of creating his movie’s aerial space battle. “Every time there was a war movie on television, like The Bridges at Toko-Ri [1954], I would watch it—and if there was a dogfight sequence, I would videotape it. Then we would transfer that to 16mm film, and I’d just edit it according to my story of Star Wars. It was really a way of getting a sense of the movement of the spaceships.

“Because one of the key visions I had of the film when I started was of a dogfight in outer space with spaceships—two ships flying through space shooting each other. That was my original idea. I said, ‘I want to make that movie. I want to see that.’ In Star Trek it was always one ship sitting here and another ship sitting there, and they shot these little lasers and one of them disappeared. It wasn’t really a dogfight where they were racing around in space firing.”

On January 10, 1974, Lucas signed a necessary if somewhat surreal legal agreement with himself, whereby Lucasfilm Ltd. loaned out “George Lucas” as director to “The Star Wars Corporation,” a subsidiary formed to facilitate the upcoming budget and legal dealings with Fox.

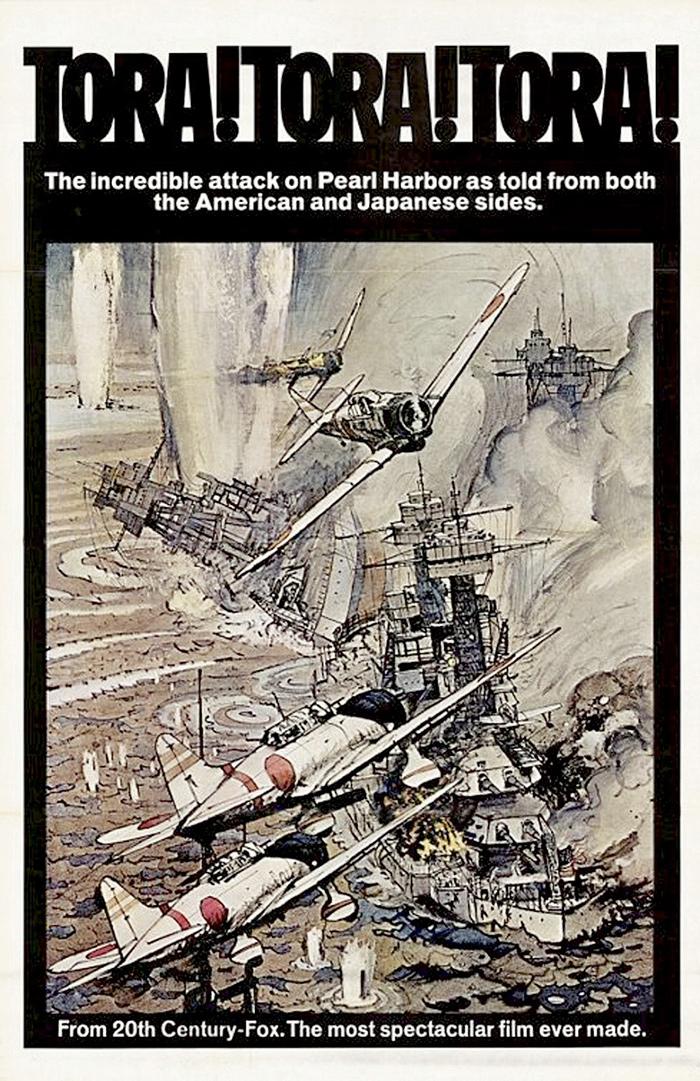

Lucas videotaped the aerial battle sequences from films such as Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) and The Dam Busters (1954) to create his 16mm film.

Throughout the winter of 1973–1974, Lucas worked on the script, writing and living most of the time alone, as Marcia was often in Los Angeles, where she was editing Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974). Kurtz was busy trying to get Apocalypse Now off the ground and thinking about developing his own films. In the spring of 1974 Lucas sometimes traveled to Tucson, Arizona, when Marcia was on location cutting the same film. He would sit on the patio, perhaps with a book or two, and write during the day. “I’ve done a lot of reading for this picture. It’s not really research so much as mythology and fantasy are taking over my life. I read everything from John Carter of Mars to The Golden Bough, so obviously all of that influences you in a certain way. I’m trying to make a classic genre picture, a classic space opera—and there are certain concepts that have been developed by writers, primarily Edgar Rice Burroughs, that are traditional, and you keep those traditional aspects about the project.”

“I remember George was writing Star Wars at the time,” Martin Scorsese says. “He had all these books with him, like Isaac Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, and he was envisioning this fantasy epic. He did explain that he wanted to tap into the collective unconscious of fairy tales. And he screened certain movies, like Howard Hawks’s Air Force [1943] and Michael Curtiz’s Robin Hood [1938].”

Lucas on his feelings post–American Graffiti. (Interview by Arnold, 1979)

(1:38)

In enlarging the treatment to what became a nearly two-hundred-page rough draft, Lucas was continually aided by the transference of his Apocalypse Now ideas to the fantasy realm. Some of his notes scribbled on yellow legal pads are: “Theme: Aquilae is a small independent country like North Vietnam threatened by a neighbor or provincial rebellion, instigated by gangsters aided by empire. Fight to get rightful planet back. Half of system has been lost to gangsters … The empire is like America ten years from now, after gangsters assassinated the Emperor and were elevated to power in a rigged election … We are at a turning point: fascism or revolution.”

While these ideas helped Lucas begin to form a plot that would go through several iterations, part of the tension inherent in his writing process stemmed from divided loyalties. On the one hand, he needed a solid structure on which to build his images: “The biggest thing was just finding a story that was interesting but not a gimmick,” he says. “I had to find a story that would do all the things that I wanted it to do.” On the other hand, Lucas’s personal tastes tended toward more abstract storytelling, in the style of Jean-Luc Godard and other directors of the French nouvelle vague. Their filmmaking style, a big influence on Lucas’s student shorts, was known as cinema verité, and it forsook much of what Hollywood had created in favor of a more emotional cinematic language. “I like Godard films. They excite me,” Lucas explains. “In film school I tended away from storytelling; I just didn’t like it—and it grew from a point of dislike to a point of real hatred. Then I forced my way back into storytelling. I thought that maybe I hated it so much because I couldn’t do it. This is one of the reasons why with Star Wars I want to attempt a storytelling film.”

Lucas’s written records from that period bear witness to just how intent he was on plot and character development as he struggled to create a strong tale: “Notes on new beginning … for three main characters—the general, the princess, the boy (Starkiller)—make development chart … Put time-limit in children’s packs … every scene must be set up and linked to next … make scene where Starkiller visits with old friend on Alderaan … Han very old (150 years)…Establish impossibility of attacking Death Star … Should threat be bigger, more sinister?…A conflict between freedom and conformity … Tell at least two stories: Starkiller becomes a man (not good enough); Valorum wakes up (morally speaking)…Valorum like a Green Beret who realizes wrong of Empire … Second thoughts about Plot … Make Owen Lars a geologist or something … The general addresses men … Skywalker leaps across (ramp being pulled away)…thundersaber …”

Lucas’s notes, scribbled before writing the rough draft, make clear the transference of his thoughts from Apocalypse Now to The Star Wars.

When Lucas changed the two bureaucrats into robots, he was tapping into a long tradition of mechanical characters, including the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Silent Running, Forbidden Planet, and even Woody Allen’s Sleeper.

He also made more lists of names and roles—“Kane Highsinger/Jedi friend; Leia Aquilae/princess; General Vader/Imperial Commander; Han Solo/friend …”—and for the first time two others are noted: “Seethreepio” and “Artwo Deetwo.” They are both listed as “workmen.” A later note contains a key transition from treatment to rough draft: “two workmen as robots? One dwarf/one Metropolis type.” The latter reference is to the mechanical woman in Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis (1926). The change of the treatment’s bureaucrats into robots may have been a result of Lucas’s sci-fi reading habits. “The law of robotics is obviously where the robots came from,” Lucas says. “Isaac Asimov invented those robots. They may not have evolved very far at all from what Asimov’s position was, or they may have evolved a great deal.”

The idea must have been pleasing to Lucas, because soon the question mark of the first note was replaced by the enthusiasm of a still-later note: “Make film more point-of-view of robots”—a thought that would have ramifications throughout the filmmaking process.

Lucas completed the rough draft in May 1974. It is a sprawling story, though once again many elements that would make it into successive drafts are present—the Jedi versus the Sith, two bickering robots, Princess Leia, Han Solo—but as before, nothing is in its final form yet. Structurally, the story contains two motivating factors that push the characters from one scene to the next: “The princess and the general were going to a neutral planet,” Lucas says, “which made it more of an escape movie, with them trapped in enemy territory and trying to get to safety. But I decided that didn’t work and that it would be much better to have it be a rescue movie instead of an escape movie.” This decision seems to have been made about halfway through the writing of the rough draft: In the first half Leia is part of the escape; once she is captured, her rescue, first on Yavin and then on the space fortress, becomes the plot’s prime mover.

Although Lucas finished the first draft two months after the rough draft, in July 1974, their stories and dialogue are identical. Only the names have been changed for many of the characters and places; Lucas had originally intended those of the rough draft to be only placeholders. One element common to both drafts is “the force of others,” which can be seen as an extension of the idea of “will” in the earlier Journal of the Whills. Lucas actually first wrote of this concept in a deleted scene from THX 1138, in which THX speaks with his friend SRT:

THX

…there must be something independent; a force, reality.

SRT

You mean like OMM. [the state-sanctioned deity]

THX

Not like OMM as we know him, but the reality behind the illusion of OMM.

From an early age, Lucas had been interested in the fact that all over the world religions and peoples had created different ideas of God and the spirit. “The ‘Force of others’ is what all basic religions are based on, especially the Eastern religions,” he says, “which is, essentially, that there is a force, God, whatever you want to call it.” It is the common denominator, a source of strength, and at this point in his writing process only the good guys seem to be aware of it. (In Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays, Laurent Bouzereau points out that the expression is a variation on the Christian phrase May the Lord be with you and your spirit—in Latin, Dominus vobiscum et cum spiritu tuo, which was often written by Saint Paul at the end of his letters.)

Lucas on the importance of myths for children and how Star Wars was designed to fill that gap. (Interview by Arnold, 1979)

(1:35)

At the time only four copies of the first draft were made. Someone got hold of a government stamp and humorously marked the copy sent to Alan Ladd, who had been waiting for some time, EYES ONLY—DO NOT COPY UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES.

“The first draft was a long time coming,” Ladd says. “We had a number of conversations about it, and seemed to be in sync about certain things.”

In addition to Ladd, Lucas gave his draft to several close friends for their feedback. His notes at the time include a list of readers— (1) Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood; (2) Bill and Gloria Huyck; (3) John Milius; (4) Haskell Wexler; (5) Francis Ford Coppola; (6) Phil Kaufman—all filmmakers.

“I run around with a crowd of writers,” Lucas says, “with the Huycks and with John Milius, and both the Huycks and John Milius are fabulous. John can just sit there and it comes out of him, without even trying. It’s just magic. The Huycks are the same way. With the first draft, I showed it to a group of friends who I help; having been an editor for a long time, I usually help them on their editing and they help me on my scriptwriting. They give me all their ideas and comments and whatnot, then I go back and try to deal with it. All of us have crossover relationships, and we are constantly showing each other what we are doing and trying to help each other.”

In a spiritual continuation of the temporarily defunct American Zoetrope, Lucas’s converted Victorian house, now known as Park Way, became a haven for many of these same friends and colleagues. “I came up and started working at Park Way in 1974,” recalls Lucy Wilson, Lucas’s first hire (who still works for Lucas), whose office was on the main house’s sunporch. “Hal Barwood and Matt Robbins shared an office there, and Michael Ritchie was there on and off. Matt and Hal were writing their movie The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings [1976]. Michael Ritchie had just done The Candidate [1972], and he was working on Smile [1975]. I think he had props down in the basement of the house. Anyway, that was fun because they were all very entertaining. George had invited these filmmakers basically to share his house with the same goal: that it would be a film community.”

“George rented out rooms in his house to various filmmakers,” Hal Barwood recalls. “And George of course had his offices there. He was living in another little house down in San Anselmo. And we would all stroll down the hill and walk off to various venues in San Anselmo and have lunch. And it was just a wonderful way, through enthusiastic conversation, to keep our interest in the movie business alive. Because the movie business is very difficult for most of us; we don’t usually get a majority of our projects to completion. Most of our dreams turn into screenplays, but then stall out at about that stage. So it was a great way for us to encourage each other.”

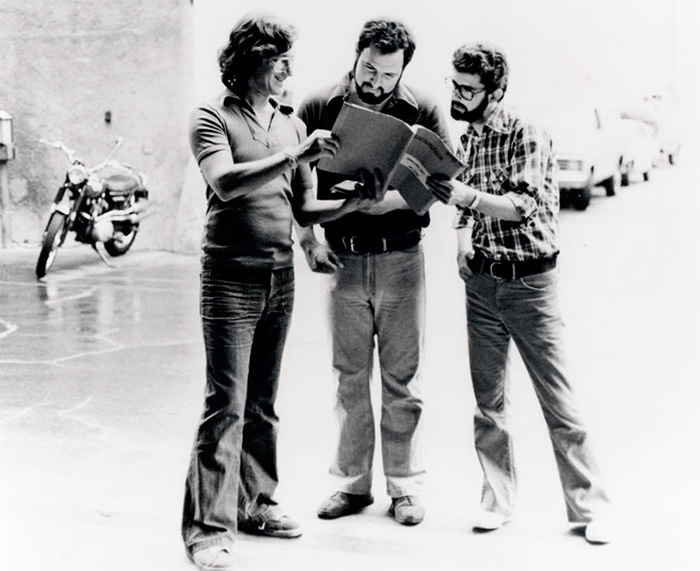

At Universal Studios, Lucas examines a script with friends Steven Spielberg and John Milius.

Lucy Wilson at Park Way.

Although experienced filmmakers, Lucas’s friends struggled to visualize his consecutive written drafts. “When people read Star Wars originally, they didn’t have a clue really,” Willard Huyck says. “It wasn’t until George acted it out or told you what a Wookee was, and what it was going to look like, that it started to make sense. Because it was really a universe that nobody could understand from the scripts.”

Nobody included Ladd, by all accounts. But by August 1974 Lucas was a well-known and respected director of a giant hit: American Graffiti had been nominated for five Academy Awards and had won several other awards, including a Golden Globe. “Fox had a very good deal,” Jeff Berg says, “a hot new name in Hollywood for very little money, and it didn’t matter too much what he wanted to do. I think that influenced Fox a great deal, because several times Laddie read the screenplay and said he just wasn’t sure what George was trying to say.”

“After Graffiti became a big hit, they couldn’t refuse it,” Lucas says. “They couldn’t not do it. Just in terms of politics and the political intrigue of Hollywood. That’s what it came down to in the end.”

Not surprisingly then, Fox decided to go to the next step in the process of making The Star Wars: a second draft, which was actually Lucas’s preference, because the movie he wanted to write into existence was proving elusive.

“I find rewriting no more or less difficult than writing,” says Lucas. “Because when you write, sometimes you rationalize away particular problems. You say, I’ll deal with that later. So I struggled through the first draft and dealt with some of the problems. But now the next step is even more painful, because I have to confront the problems in a more serious way.”

Even as he went through the headaches of writing a second draft during the summer and winter of 1974, another source of disquiet began to gnaw at Lucas: the contract. Although he had an agreement with Twentieth Century-Fox, they were hesitating before taking the next legal step. Standard practice at that time in Hollywood was for the production-distribution contract to follow two or three months after the initial agreement, as had been Lucas’s experience with Universal on American Graffiti. But the question of how The Star Wars was going to get made, and how much that answer was going to cost, was causing anxiety at Fox. So in lieu of doing something decisive, they delayed doing anything.

“I got mad about a year after I had started working on it,” Lucas says, “working and working and working, and they wouldn’t give me a contract. They were saying, ‘Well, he didn’t really finish the script, either’—but writing a contract is different from writing a script. A script is a creative work that you are trying to eke out while coming up with something good.” Or as Lucas’s lawyer Tom Pollock puts it: “It was not until late 1974 that we even got a piece of paper out of Fox because they are so fucking slow.”

Lucas used the law offices of Pollock, Rigrod and Bloom to translate his anger into what were to become harder- and harder-edged negotiations—if Fox was going to be nonresponsive, he was going to concede nothing. Pollock instigated several discussions with studio exec William Immerman, followed by a meeting with Immerman and Jeff Berg on August 23, 1974. The upshot was Pollock’s summation letter dated September 4, with further amendments to the Memorandum Agreement (deal memo), some of which had long-ranging implications. Paragraph 1 states: “The Star Wars Corporation will own … all sequel rights [to] the screenplay ‘The Star Wars.’ ” Paragraph 5 addresses “merchandising rights and commercial tie-ups,” with 5.B stipulating that “Either party may license merchandising rights … subject to the other party’s bettering the licensing deal.” Item 5.D states “SWC shall have the sole and exclusive right to use … the name ‘The Star Wars’ in connection with wholesale or retail outlets for the sale of merchandising items.”

Fox responded with another period of silence, followed by a second letter from Pollock, written on December 17, 1974: “It is very important to me and to George Lucas that these matters be settled at once.” Immerman finally replied on December 27, optimistically writing, “I believe … we can therefore proceed with preparation of a formal contract.”

But at that point, with nothing actually agreed upon, the correspondence petered out. Oddly, the rights being argued about were not considered potentially valuable, as the studio, with the exception of Ladd, had very little faith in the film or its director. Other forces were at work. “My perception is, there was a lack of respect for George,” Warren Hellman says. “The movie industry is a very vituperative and petty industry most of the time—and part of the negotiations was just to see how much they could push George around because they felt like they could.”

Though Lucas was not pleased with how things were going with the contract department, he dutifully did his part in advising the studio’s production department on his own progress. “George went off to write and the next draft was to be delivered twelve weeks later, according to the deal memo,” Alan Ladd says. “In twelve weeks’ time, George called to say he hadn’t forgotten about it and that it would be here soon. Then some more time went by, but I always kept thinking to myself, Well, next week it will be here…”

While Marcia helped edit Scorsese’s next film, Taxi Driver (1976), Lucas spent more time alone, making notes before committing to the second draft. “Sith knights look like Linda Blair in Exorcist [1973],” he wrote, as the bad guys are rechristened the Sith. “Vader—do something evil in prison to Deak,” he wrote, as General Vader becomes a Dark Lord of the Sith, and Deak reappears as a brother, this time to Luke—the name of a boy, not a general, who replaces Annikin/Justin as the story’s main character. “Luke reluctantly accepts the burden (artist, not a warrior, fear); establish Luke as a good pilot … farm boy: fulfills the legend of the son of the sons; pulls the sword from the stone. All he wants in life is to become a starpilot.” Leia is also brought back from the rough draft, as Luke’s cousin, a secondary character: “Leia: tomboy, bright, tough, really soft and afraid; loves Luke but not admitting it.” Lastly, Solo metamorphoses from alien to humanoid in Lucas’s notes: “Make Han in bar like Bogart—freelance tough guy for hire.”

Other notes for the second draft contain pieces of scenes and ideas that didn’t make it into the actual script: “Jabba in prison cell”; the love relationship between Leia and Luke Starkiller is divided into “seven stages/crucial scenes,” with her being crowned queen at the end; “Han Solo a Wookiee? Wookiees talk to plants and animals.” Lucas also analyzed and wrote notes on films he saw, such as John Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945) and Ben-Hur (1959).

Lucas’s habit of working and observing no matter where he was helped create and crystallize the character of Chewbacca the Wookiee. For many years, Lucas had an Alaskan malamute named Indiana, who would often sit in the passenger seat of his car. People driving by would sometimes express surprise that what they perceived from behind to be a person turned out to be an enormous canine. Amused, Lucas slowly combined Indiana, the Wookiees of Yavin, and the name Chewbacca into Han Solo’s copilot: a great big, intelligent, friendly-but-fierce dog-creature sitting by his side.

As the weeks and months wore on, however, the difficulties of facing the blank page only increased for Lucas. “You go crazy writing. You get psychotic,” he says. “You get yourself so psyched up and go in such strange directions in your mind that it’s a wonder that all writers aren’t put away someplace. You can just get so convoluted in what you’re thinking about that you get depressed, unbearably depressed. Because there’s just no guideline, you don’t know if what you’re doing is good or bad or indifferent. It always seems bad when you’re doing it. It seems terrible. It’s the hardest thing to get through.”

Lucas struggled to meld many diverse influences into one story: swashbucklers, comic books, science fiction—and creature features, such as The Wolfman (1941). Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) had been banned in the U.K. for thirty years and in many cities and states in America, but was notably revived during the 1960s, when it played in the LA area at the Cinema Theatre.

Still in a state of dissatisfaction, knowing it was still far from a shooting script, Lucas finished his second draft on January 28, 1975. A copy in the Lucasfilm Archives features a red cover with a Frank Frazetta–like illustration of a man holding a sword with an adoring, voluptuous woman wrapped around his leg.

Lucas had clearly made major changes to the structure of his story between the first and second drafts. It’s at this point that the well-known break occurred, when, having written something that was far too long for one movie in the first draft, he decided to begin the second draft in the middle of the first—at the moment the robots escape. In the first draft, they flee the Death Star; in the second, now on the side of the good guys, they flee a besieged rebel starship. One of his notes summarizes Lucas’s thinking: “Whole film must be told from robots’ point of view,” a further development of the device of the two peasants in Hidden Fortress.

While at one time Lucas contemplated making two movies out of the first draft—ending the first with the escape from the Death Star, and having the second start with the crash landing on the jungle planet, and close with the attack on the space fortress—instead he combined and juxtaposed many of the more exciting scenes into a shorter, tighter single film. Another of his notes on structure reads, “time lock” to add suspense: “the empire has a terrible new weapon, a fortress station so powerful it can destroy a planet, possibly even a sun. It must be stopped before it can be put to use.” By transforming the space fortress from a floating, somewhat meandering locale, in the first draft, into a horrific planet-destroying weapon, Lucas turned it into a character as well as an all-important structural element.

Though augmenting the role of the two robots, he jettisoned other Hidden Fortress elements. The general is no longer a major character, literally sleeping through some scenes, and the princess has disappeared completely; in their place, the character of Justin/Annikin, now Luke, has taken center stage. His adventures with the robots, while still picaresque, form the line that goes through the story. Indeed, the character of the young Jedi Annikin/Justin has been split in two: Han Solo takes on his womanizing ways and cavalier attitude, while Luke embodies his serious side, his metaphysical side. Both possess the attributes of the time-honored bildungsroman character—the one who comes of age before our eyes.

Luke’s journey is told in part through his relationship with the Force, which in the second draft is more thoroughly analyzed. It now has a dark side, which the bad guys can use—thus enhancing their power to almost equal that of the good guys, conforming to Alfred Hitchcock’s observation that the greatness of a hero is defined by the magnitude of the villain he or she must overcome.

All in all, the second draft is a radical reworking of the first. “While I was writing the rough draft, they ended up in this cantina about halfway through; they walked in and there were all these monsters,” Lucas says. “When I wrote the second draft about the only thing that remained was the cantina scene and the dogfight.”

The cinematic swashbuckling element was represented by Errol Flynn in Captain Blood and The Adventures of Robin Hood (with Basil Rathbone), and by Stewart Granger in Scaramouche.

A photo of George Lucas taken in March 1973.

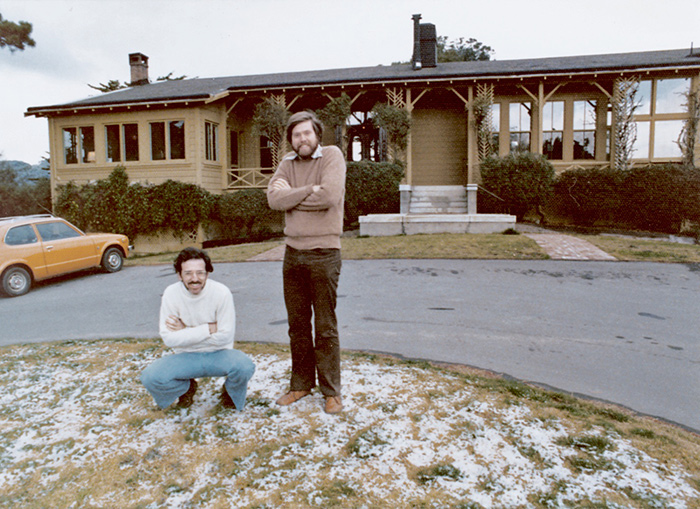

On a rare snowy day in Marin County, Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood pose for a photo taken by Lucy Wilson in front of Park Way house.

Not surprisingly, Alan Ladd was a bit perplexed. “In came another script and it had a lot of different scenes and a lot of character changes,” he says. And though the script was more streamlined, Lucas’s idea of the serial—crystallized with the addition of Episode I to the title, and an end roll-up that promises more adventures—must have added to Ladd’s confusion. For that matter, anyone reading through these drafts would be alternately amazed and thoroughly befuddled by the constant shifting of sands, the experience affording a glimpse into the mind-set that Lucas consistently describes as unsettling.

Even Coppola was startled: “My recollection was that George had a whole Star Wars script that I thought was fine,” he says, “and then he chucked it and started again with these two robots lost in the wilderness. I remember thinking that the first script he showed me was really good and I was sort of curious as to why he was, you know, dumping that.”

“It started off in horrible shape,” Hal Barwood says. “It was difficult to discern there was a movie there. It did have Artoo and it did have Threepio, but it was very hard for us to wrap our heads around the idea of a golden robot and this little beer can. We just didn’t know what that meant. But George never gave up and he worked and worked and worked.”