The delivery of the second draft in early 1975 didn’t make a difference in The Star Wars Corporation’s negotiations with Fox, which still declined to make a financial or legal commitment. The studio remained extremely dubious as to how much Lucas’s ambitious scripts were going to cost to film, particularly because no official budget had yet been submitted. “For a couple of years after the initial negotiations,” Andy Rigrod says, “there were no formal agreements and basically George was working out the script and working out the budget, which started at about $3 million.”

Office stamp for the company formed as a subsidiary of Lucasfilm during production of The Star Wars.

To remedy the situation, in addition to making notes for a third draft, Lucas employed Kurtz to formulate a more realistic budget. “After the second script, Gary really wanted to get started on something,” Lucas says. “I had already taken a year and a half to write, and he wanted to get the production going.”

The budget stall came from the fact that no one knew what anything was going to look like, so no one could calculate costs. The solution was to hire artists to create production illustrations and models that would provide something tangible on which to base estimates. Lucas had actually hired one of the artists back in November 1974, though he wasn’t able to actually start a painting until late January, finishing it a couple of days later on January 31, 1975.

“I had been doing a stint as an animator at this little industrial film company [circa 1968],” Hal Barwood recalls. “One of the clients for the film company was the Boeing aircraft corporation, which at that time was designing the supersonic transport, the SST. I met a guy who was doing concept paintings for it, and they were just stunning. It was this guy named Ralph McQuarrie.

“A few years later [circa 1973], Matt and I were working on our film Star Dancing,” he continues, “so we tracked Ralph down in LA and he turned out these paintings. When we were ready to go see them, it just happened we were having lunch with George and he said, ‘Hey, I’ll tag along.’ So we looked at these paintings and George said, ‘You know, I’m gonna make a science-fiction movie someday. Maybe we’ll get together.’ And that was the beginning of the relationship with George and Ralph.”

“George saw the work that I did for Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins,” Ralph McQuarrie says. “They had a real neat science-fiction script that they wanted to do, which a lot of people were interested in, though it never did get done. George talked about his idea for an intergalactic war picture. And I thought, ‘Gee, that sounds ambitious.’ And we said good-bye and I never expected to see him again. But a couple of years later [laughs] he comes back with the idea of me doing some illustrations like I did for Hal and Matt. I said, ‘Great, I’d love to.’ So George came over with the script one afternoon, and we arranged for a weekly salary.

“From what I understand,” he adds, “Fox was all set to go, just on the strength of the basic idea, but they hadn’t picked up their option. There might have been some slight hesitation. It seemed to me the paintings were of interest to them because they were concerned about how these things would look. I think they were done as a substitute for arm waving and verbal descriptions, and to start budget talks.”

At their first meeting, Lucas showed McQuarrie the same illustrations he’d originally attached to his treatment, plus a couple of inspirational pieces pulled from comic books for Luke’s landspeeder, and a drawing of a lemur for Chewbacca. He also made several sketches to demonstrate what he wanted.

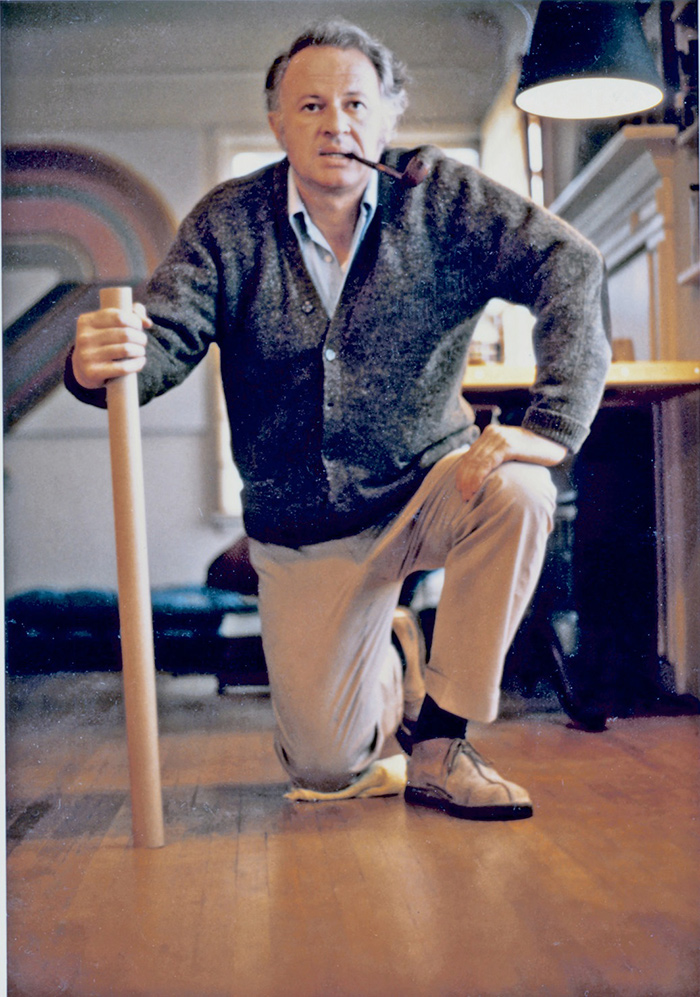

Ralph McQuarrie at work on the CBS News Apollo coverage.

McQuarrie posing for his Winterhawk poster.

His painting for Star Dancing, a Hal Barwood/Matthew Robbins film that never got off the ground, shows an astronaut on a planet covered with wheat. (The astronaut discovers an underground alien installation; later he meets the aliens themselves, who come back every year.)

During their first meeting in November 1974, Lucas drew three sketches—a TIE fighter, X-wing, and Death Star—to show Ralph McQuarrie what he had in mind, perhaps the first conceptual record of these designs.

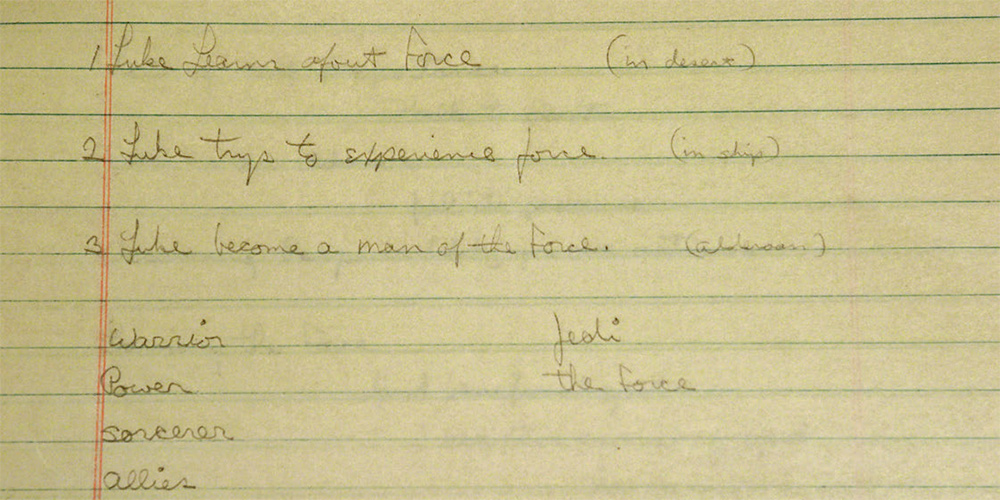

Born in 1929, McQuarrie had attended Art Center from 1954 through 1956, studying advertising design. If he had answered American Graffiti’s question, “Where were you in ’62?,” his answer, according to a bio he wrote, would have been, “dropped out; read books; walked on beach; Zen; not sure what I want to do.” The stopgap solution was to return to Boeing, where he had first worked in 1952 following two years of military service in Korea. As of 1968 he began working on the CBS News Apollo coverage, eventually segueing into freelance illustration work for filmmakers. For the somewhat itinerant artist who had been drawn to the fantastic since he was a child, the chance to do space-fantasy illustrations for The Star Wars was great fun. “I felt, oh yes—this is what I was meant to do.”

“George would come into Universal Studios [to Kurtz’s office] and go visit Ralph at his home in Los Angeles,” remembers Kurtz’s assistant, Bunny Alsup. “And basically, I felt that Ralph McQuarrie was very quiet. He’d come in as if he weren’t there and he would listen, and they would talk and they were all enthusiastic; they were all happily working, trying to tune in to the same finite idea.”

Describing their collaboration, Lucas says: “I have a list of about ten scenes that I want to have painted. He does a rough sketch and then I correct the rough sketch, and then he does another rough sketch and I correct that, and we keep doing it until I feel we’re close enough to where he can do a big drawing. So he does a big rough sketch just as big as the painting; I correct that and then he paints it. But Ralph also adds in an enormous amount of his own detail, his own textural and design elements, which are a great help. I just describe what I want and then he does it. I show him a lot of research material, a lot of things I’ve picked out, and he combines that with other things and invents a lot.

“That was the first step,” he adds. “I really trusted him. Sometimes it was great, and sometimes we had to go back and change it and start over again.”

“George wanted me to do sketches, and we did those in the course of getting straight between us both what the thing should look like,” McQuarrie says. “He wanted the illustrations to look really nice and finished, and the way he wanted them to look on-screen—he wanted the ideal look. In other words, don’t worry about how things are going to get done or how difficult it might be to produce them—just paint them as he would like them to be. So we approached it like that, and I finished four key moments that he felt he definitely wanted to see. So as much as I designed this, George really designed it, too.”

Although often counted as four, McQuarrie actually painted five moments from the second draft (the reasons why only four are counted will become apparent later). One of those was the confrontation between Vader and Deak Starkiller.

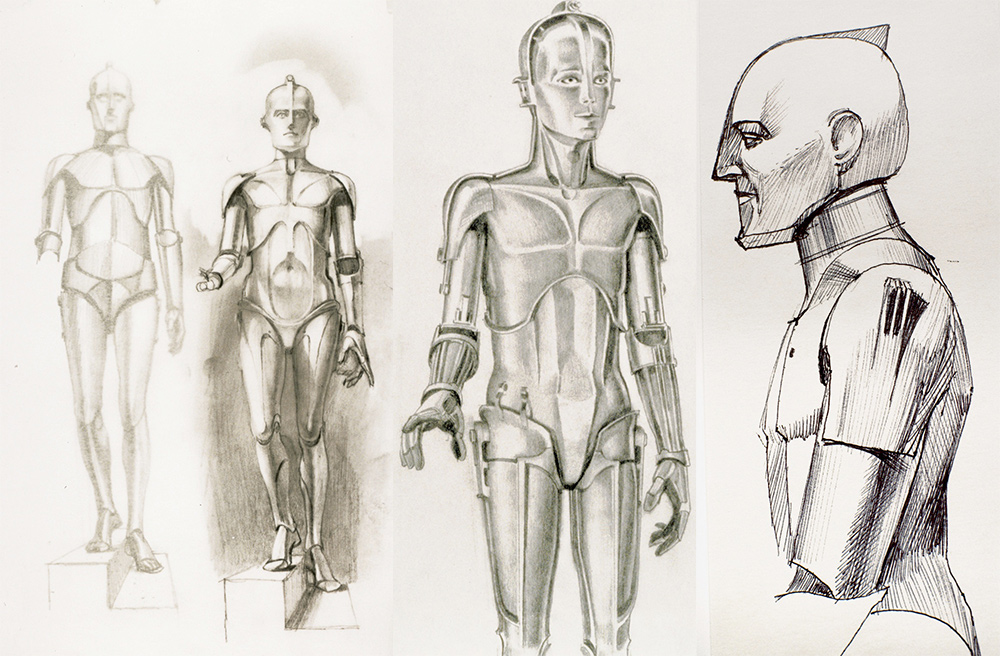

“For Darth Vader, George just said he would like to have a very tall, dark fluttering figure that had a spooky feeling like it came in on the wind,” McQuarrie says. “He mentioned the look of Arab costumes, all tied up in silk and rags. He liked the idea of Vader having a big hat, like a fisherman’s hat, a big long metal thing that came down. George wanted him to have some sort of mask, because they were supposed to leap down from this big ship to a smaller ship that the rebels were in. The space suits began as being necessary for their survival in space, but the suits became part of their character. I made three or four little sketches, which he looked at and said, ‘That’s not right, I kind of like that hat, but maybe you should fool around with it a little bit more.’ So I made some more sketches. He was going up to San Francisco to work on the script, and came down in another week and a half or two weeks to see what I was doing.”

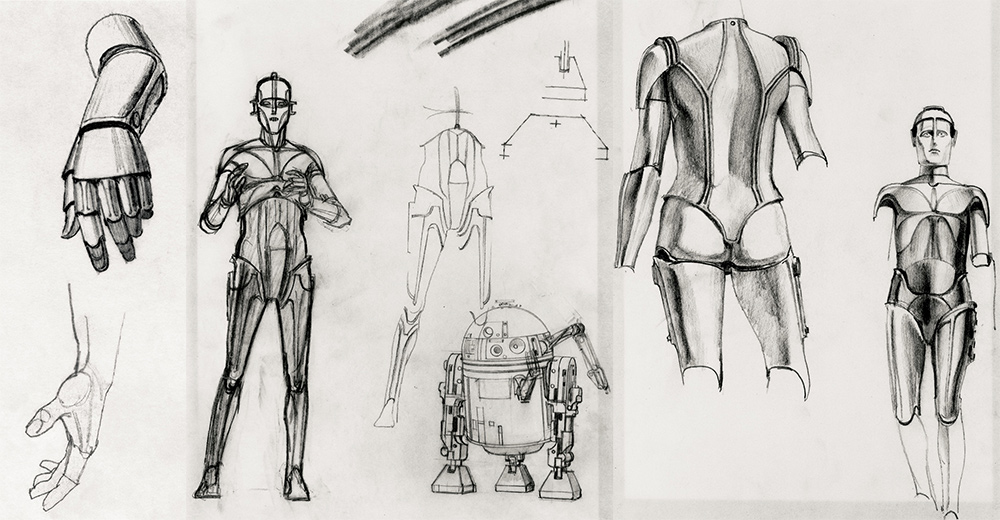

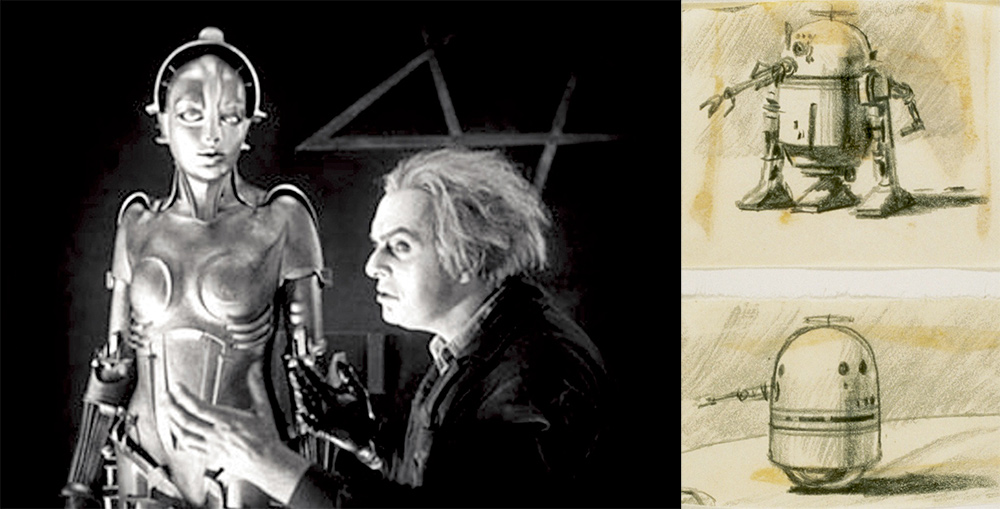

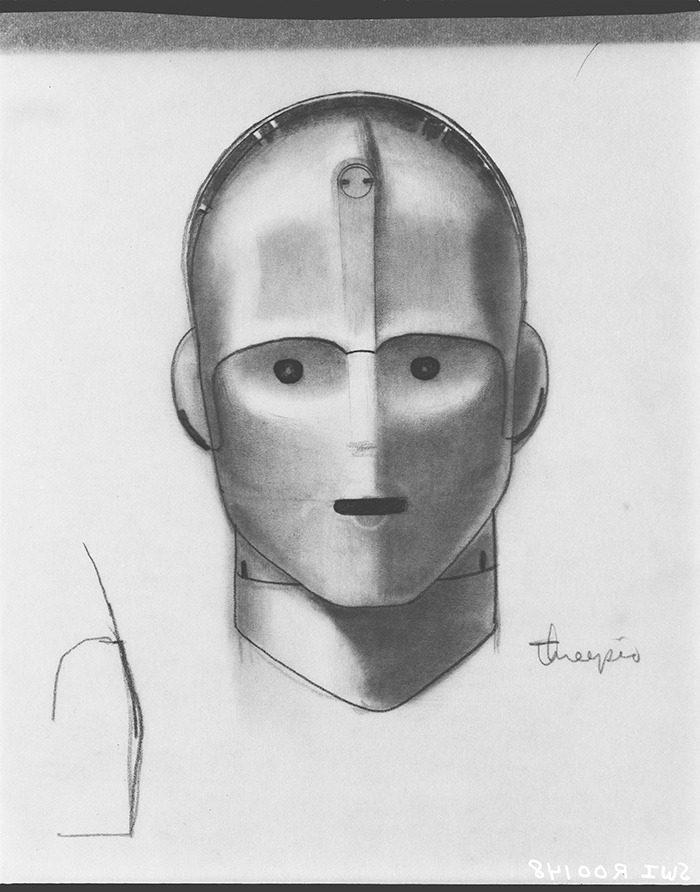

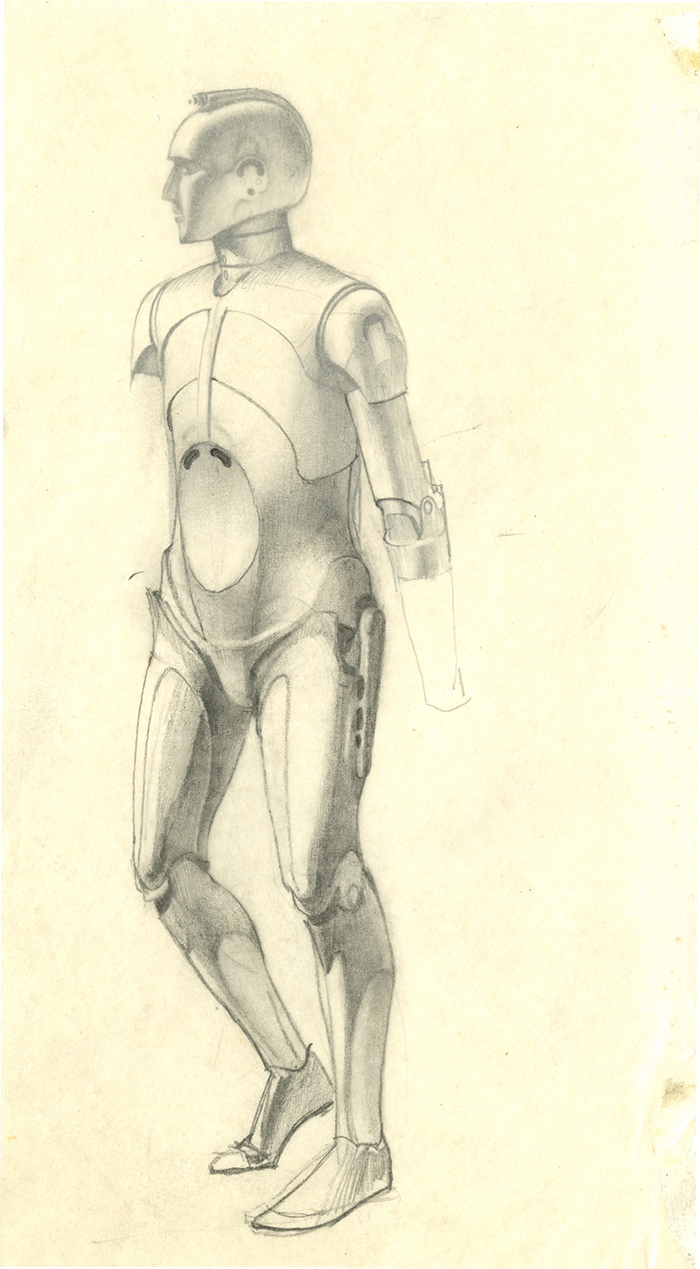

Starting in November 1974, working from Lucas’s verbal descriptions and visual references, and using Fritz Lang’s Metropolis as a guide (with Alfred Abel), McQuarrie drew his first sketches of R2-D2 and C-3PO. One sketch contains a tiny figure that recalls the alien from The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Another artist hired was Colin J. Cantwell, whom McQuarrie says was on the production before him, but only by days or weeks; accounting records show that both began to be paid in November 1974. Once again Hal Barwood was instrumental, having recommended the model maker to Lucas. “I went out to see this thing he was doing for the San Diego planetarium space show,” Lucas says, “and I hired him to help me with some models.”

Like the production paintings, the models were being built to help formulate the budget—but they were also important to the film’s special effects, which Lucas knew would make extensive use of miniatures. Cantwell was one of “the class of 2001,” having worked with Douglas Trumbull on Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1968 film, as well as with Trumbull again on The Andromeda Strain (1971). An experienced model maker, Cantwell also had a tremendous collection of space models and gadgets at his home, acting at times as a “space consultant.”

Lucas worked with Cantwell as he did with McQuarrie, providing reference material, verbal descriptions, and his own sketches. Work with the model maker went more slowly, but as Lucas signed off on approved spacecraft, McQuarrie incorporated them into his paintings.

The third artist the director hired was Alex Tavoularis, who started in mid-February 1975 to draw out storyboards of the opening sequence to help calculate the costs of those special effects shots. Alex was part of Coppola’s circle, the brother of production designer Dean Tavoularis, who had worked on The Godfather.

Although the trio’s work was specifically designed to get the film made, Fox would not pay for any of them. And the $15,000 they’d given for development was nothing near what was needed; Cantwell alone would cost $20,000. Lucas was thus obliged to pay them out of his Graffiti profits. If not for his cash, it’s very possible that The Star Wars might have irretrievably stalled.

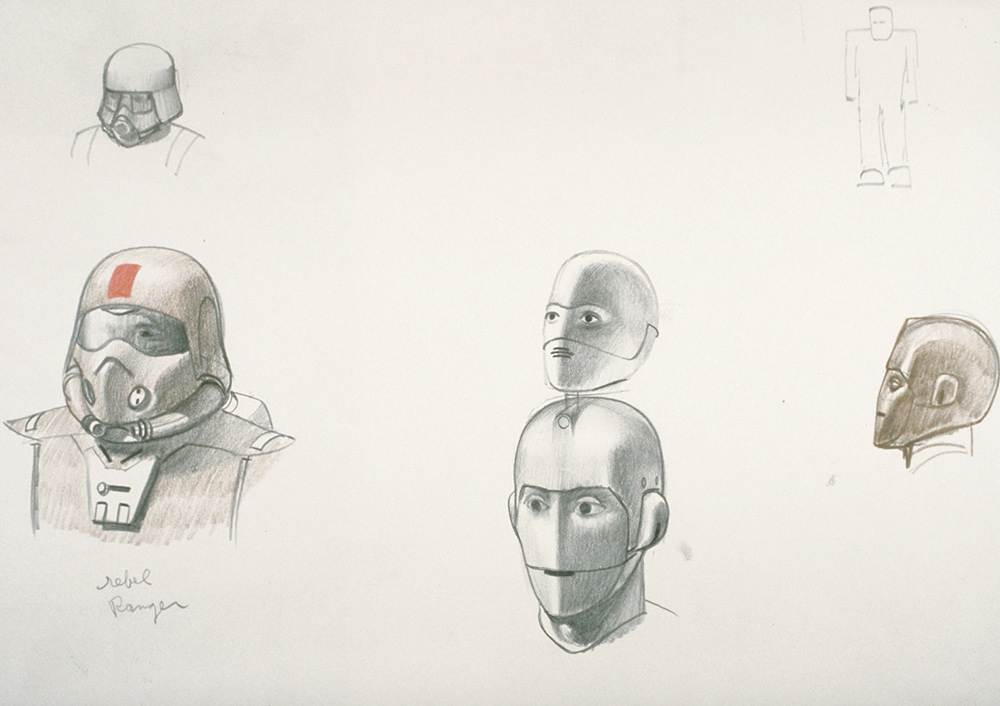

McQuarrie’s early sketches for Darth Vader. In one (top left), Vader brandishes what looks like an épée from a swashbuckling film.

“There was basic apathy toward the project within Fox,” Warren Hellman says. “The studio hoped a lot of times that it would just go away.”

“It was the same thing with American Graffiti,” Lucas notes. “The only thing in the end that got Graffiti done was my persistent, dogmatic attitude that the movie was going to get made one way or the other. I was really in no position to get a movie made, but I knew that that movie was going to get made and I just did everything that I possibly could to have it happen. There was never a question in my mind that it wasn’t going to be finished. Star Wars was a little more dubious …”

Or as Kurtz says, “Each step we dragged Fox along.”

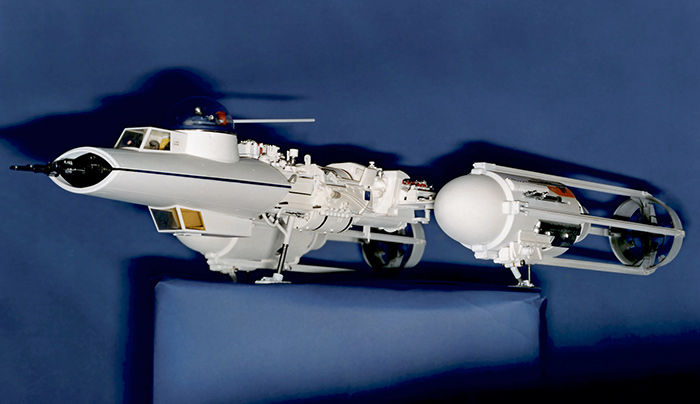

Perhaps the first concept model approved was Colin Cantwell’s Y-wing—which the model maker showed in his studio to Lucas. Like several artists who were hired for The Star Wars, Cantwell had worked on Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001, which also served as early inspiration for Lucas.

“In the first conversations George said that he wanted to do something very different from 2001,” Cantwell says. “He wanted the movie to be as immersive and as new as 2001 but George wanted to make this action saga with a comicbook nobility.”

April 1975 marked the beginning of what can only be described as a mind-boggling overlapping of activity for Lucas and company. If the first two years were marked by the horror of the blank page and the agony of writing, the next two years very likely left little time to feel anything. On or a few days after April 5, 1975, Kurtz traveled to London, taking all of McQuarrie’s paintings with him to use as reference when interviewing potential department heads, because the next step was getting things going in England. Moreover, the more The Star Wars operated as a working production, the more likely Fox would begin to back them financially.

“Why England?” Kurtz asks rhetorically. “Because it was the solution to a multifaceted problem. There was the cost factor. Certain things are cheaper in certain parts of the world. We had investigated Spain, Yugoslavia, and several other countries, and we’d come up with what we thought was the best compromise. We also wanted locations for the desert planet to be in North Africa, and it’s much closer to North Africa from England than from the United States. We could find deserts elsewhere—New Mexico, Arizona, or Old Mexico, Central America, either very good or spectacular—but we wanted slightly bizarre architecture that still looked real. Also we wanted an English cameraman, with a certain level of technological sophistication.”

Lucas and his producer had done the math that showed the United States would cost almost twice as much as England in some below-the-line areas: that is, crew costs. With Fox already panicked about the budget, these savings were essential.

Before joining Kurtz in London, Lucas made a significant alteration to the second draft during the last couple of days in March 1975: He changed Luke into a girl. “The original treatment was about a princess and an old man,” Lucas explains, “and then I wrote her out for a while, and the second draft didn’t really have any girls in it at all. I was very disturbed about that. I didn’t want to make a movie without any women in it. So I struggled with that, and at one point Luke was a girl. I just changed the main character from a guy to a girl.”

Lucas then flew to England for a one-week stay. “We started interviewing cameramen and art directors first,” he says. “Because those are the two key people you have to line up early. They are booked way in advance. First, I made a list of all the people in England whose work I admired and all the films I thought were well shot. I had certain ideas of a few guys that I was really high on. Then we interviewed lots and lots of people, practically everybody.”

Among the cinematographer candidates were David Watkin, Gil Taylor, Anthony Richmond, Dick Bush, and Peter Suschitzky; among the art directors, Michael Stringer and Brian Eatwell. At the time, Lucas was trying to decide between going with younger, less experienced people, who would perhaps have more enthusiasm, or choosing more experienced but perhaps less flexible veterans.

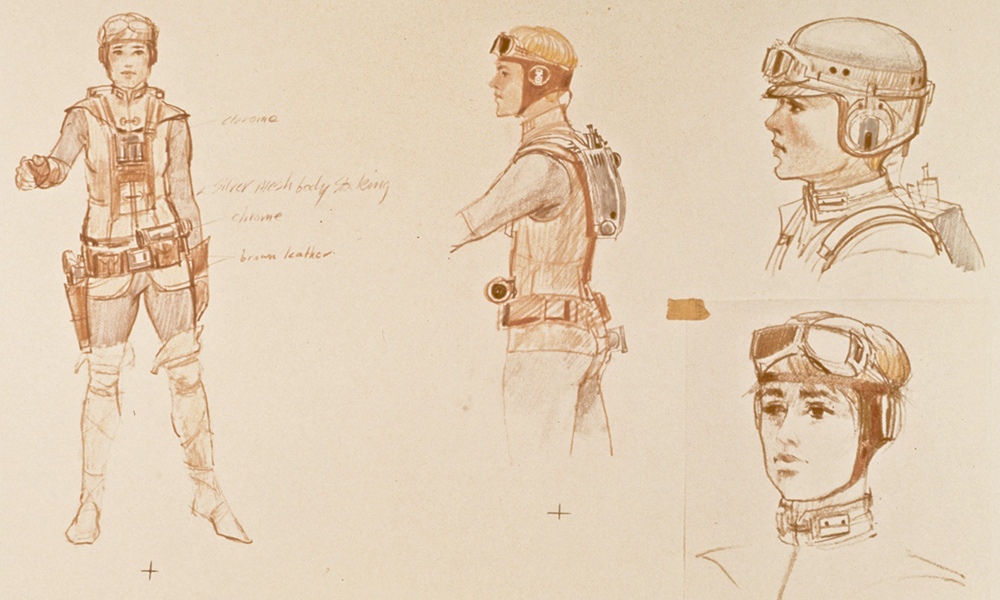

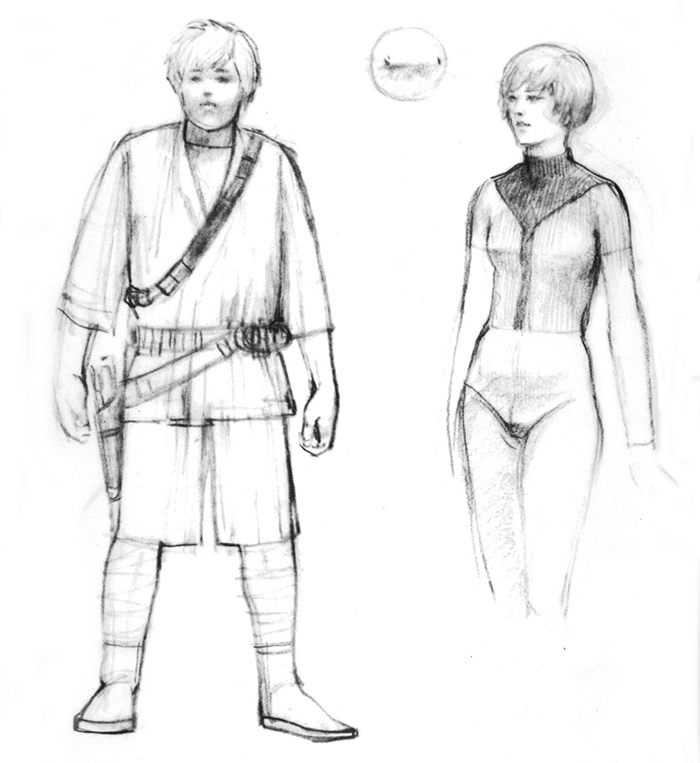

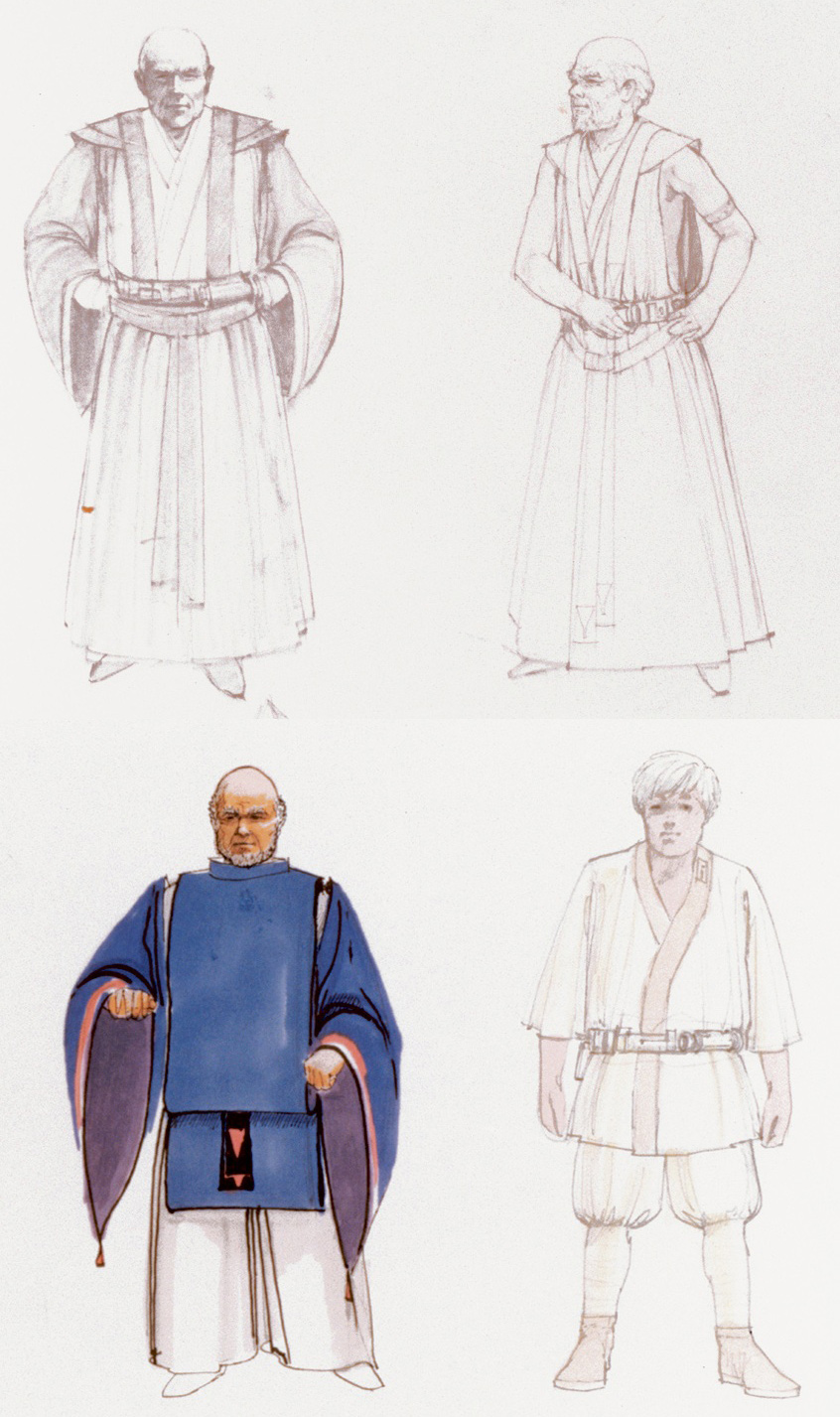

A McQuarrie sketch shows costume concepts for the Luke-as-girl character.

“I talked with them to find out what their personality was like and about their philosophy of film,” says Lucas, who had dinner with at least one. “Then we narrowed it down to two or three people of each. Some of them couldn’t do it because they already had other commitments.”

Separately, Kurtz saw production supervisor candidates and surveyed all the London studios during a “whirlwind” trip, compiling a list of sound stage sizes and investigating postproduction facilities. To help with budget estimates and hiring, Fox hired a local consultant for two weeks: production designer Elliot Scott, who began by reading the revised second draft. One of his first recommendations was special mechanical effects supervisor John Stears.

“Scott called me,” Stears says, “and said he had a picture with a certain amount of problems effects-wise in it, and would I like to go and talk to him, which I did. I read the script as it was then, and I started a feasibility study for Fox. It was a question of talking to the director: long talks about the feel of the movie, and what’s physically, technically, and financially possible within the budget.”

A former matte painter who also had a license to work with explosives—essential to his work on several James Bond films of the 1960s—Stears began by talking with electronics and engineer specialists, along with camera mechanics.

“Stears had actually gotten on the movie before I even got to England,” Lucas says. “He had been brought in by Fox to do some preliminary estimates, so when I got over there to look at it, they had done a preliminary budget; he and Elliot Scott had worked on it, and Stears stayed on because he had such a good reputation. Everybody said he was one of the best and there weren’t a lot of other guys of the same caliber available.”

But even with the aid of concept art and consultants, Kurtz found it difficult to pin down a realistic budget. “I came up with a $15 million and a $6 million and $10 million budget,” he says. “And it was totally arbitrary. You have to design the sets before you know how much things are going to cost.”

Between the second and third drafts, Lucas wrote a six-page story synopsis. Dated May 1, 1975, it served as a primer for Fox executives short of time who needed to understand what the movie was about. Not long afterward Lucas, uncharacteristically, typed out a new outline in four single-spaced pages as he continued to fight his way toward a story. The combined efforts contain key developments. About a month after changing the main character into a girl, Lucas changed her back into Luke, while at the same time resuscitating the princess.

“It was at that moment,” says the writer, “that I came up with the idea that Luke and the princess are twins. I simply divided the character in two.”

The concept had already been germinating in his mind: Biggs and Windy began as twin-like princes in the rough draft, becoming actual twins in the second draft. The desert planet also has twin suns. No doubt in his readings Lucas had come to appreciate the mythological significance of twins, which have been regarded as sacred by many cultures since the beginning of recorded history. Their use as a literary device for defining characters in relation to each other was also helpful: “The princess is everything Luke wants to be,” Lucas says. “She is socially conscious, whereas he is thrown into things; intellectually, she is a strong leader, and he is just a kid.”

Indeed, her character is so strong, even in the abbreviated synopses, that she eclipses Deak, who nearly disappears from these notes, surviving only as an unnamed “Captain.” On the other hand, an unnamed older Jedi appears for the first time. This elderly man is, quite literally, the wizard on the side of the road, whom the hero meets on his journey. In exchange for his teachings, the old man requests payment in the form of food, which recalls Kurosawa’s seven samurai who are paid with rice by farmers to protect their village.

In the outline Lucas refers to the old man’s mystical powers as being like those of “Don Juan”—a reference to The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge by Carlos Castaneda, which was first published in 1968, with sequels in 1971 and 1972, followed by Tales of Power in 1975. Castaneda’s fictional Don Juan Matus is like a shaman, with the ability to shape-shift, who teaches the mastery of awareness—to the point where one may keep it beyond death. His mystical influence seems to have been key in transforming Lucas’s concept of the Jedi from a samurai warrior into a more mystical warrior.

A sketch by Alex Tavoularis is one of the first to show Princess Leia.

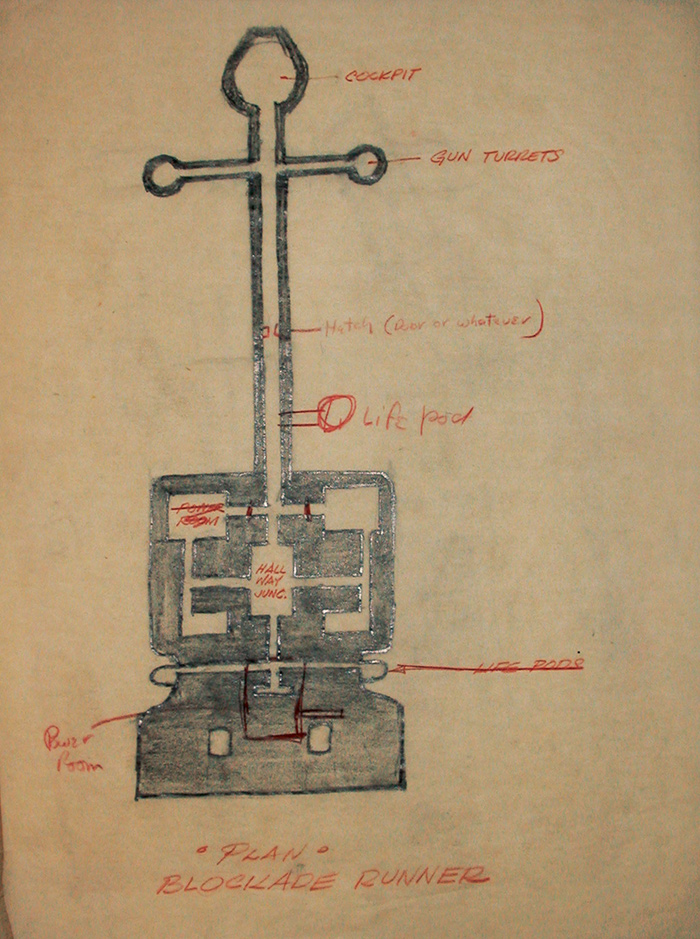

A sketch by perhaps Colin Cantwell shows her rebel ship, with notes indicating which action takes place where.

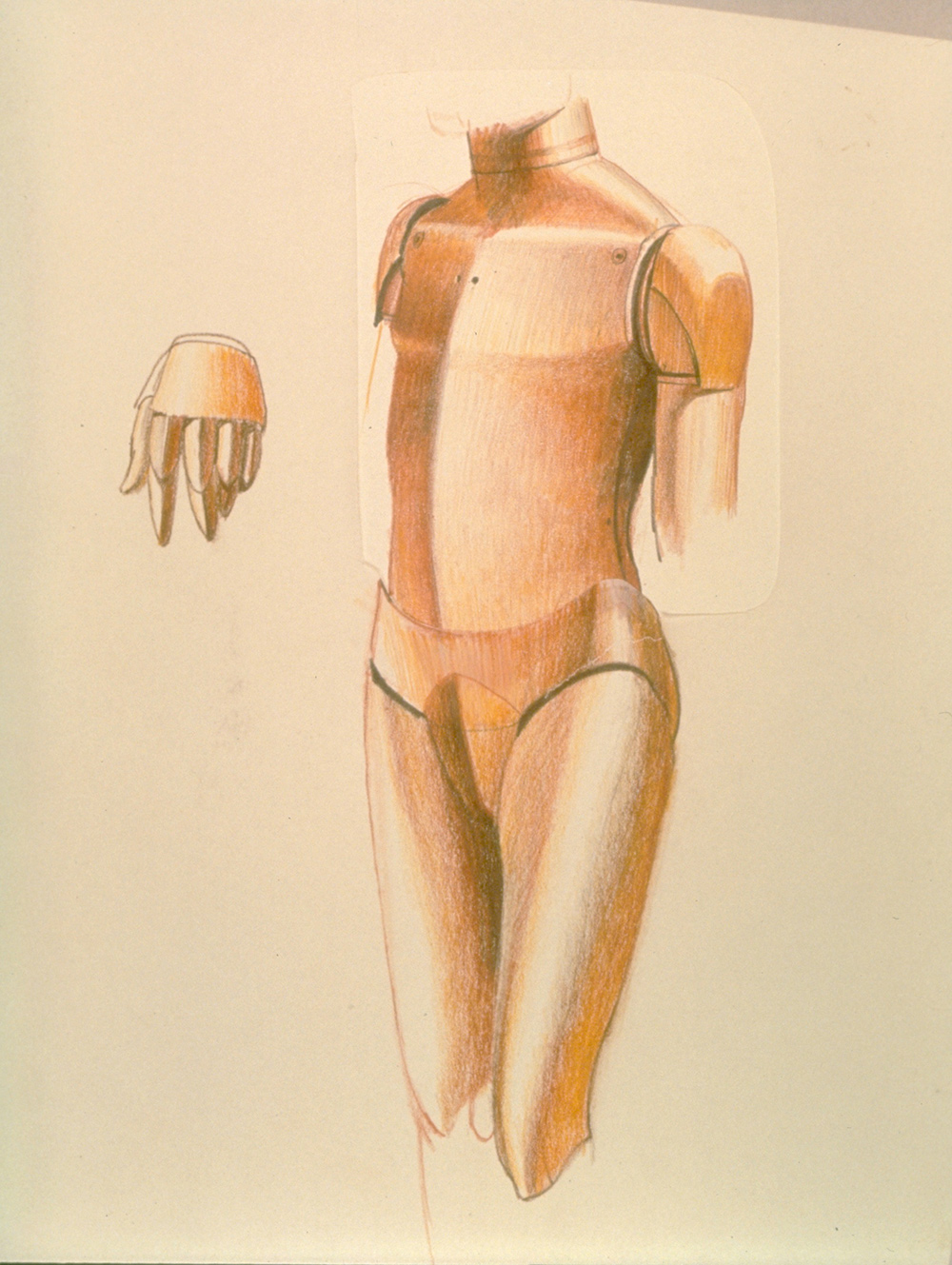

An early character-costume sketch reveals how closely linked visually Luke and Leia were; though not explicitly stated as being twins, the idea was present in Lucas’s mind and may have been communicated as such to McQuarrie.

“I spent about a year reading lots of fairy tales—and that’s when it starts to move away from Kurosawa and toward Joe Campbell,” Lucas says. “About the time I was doing the third draft I read The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and I started to realize I was following those rules unconsciously. So I said, I’ll make it fit more into that classic mold.”

More scholarly and perhaps as mystical as Castaneda, Joseph Campbell wrote that all mythical stories of the hero—cross-culturally and across history—contain the same elements, which can be classified as a monomyth. Although there are variations, essentially the hero receives a “call to adventure,” undergoes adventures and trials, and eventually surpasses his mentor and achieves an apotheosis.

The influence of these two writers, and others, can be felt not only in the philosophy but also in the developing structure of Lucas’s story, to which he made several changes: The Kiber Crystal moves from the moisture farm to Alderaan, where the old man has to search for it; instead of Deak it is the princess, a character more integral to Luke’s heroic journey, who is rescued; and the attack on the Death Star is supplemented, perhaps because Lucas was searching for a more physical confrontation, with a duel between Luke and Darth Vader, who fight on its surface.

Although Lucas had made the decision to shoot in England and North Africa, he decided to create his own special effects house in Northern California. The two primary reasons for doing so were cost and control. By having his own facility, Lucas could authorize the making of specialized equipment, hire his own people, and keep an eye on production. If a film frame had to sit three days in an optical printer, his effects house would have that luxury. “Once we added up the cost, it was just cheaper and easier to control the elements by doing it ourselves,” Kurtz says.

Lucas had talked with others, doing due diligence. He had discussed the project with the few specialists in the area, Howard Anderson and Linwood Dunn, as well as Jim Danforth and Phil Taylor. Douglas Trumbull, who had supervised the effects on 2001, might have been a candidate for special effects supervisor, but he was more interested in directing, having recently completed Silent Running.

“I learned everything I could about special effects in school,” Lucas says. “I got the books and read everybody. But I hadn’t worked very extensively with special effects and optical problems, and there aren’t that many people around who know this kind of stuff anymore.”

In April 1975 the director met with John Dykstra, who had assisted Douglas Trumbull on 2001, Silent Running, and many commercials. “I was working for Doug at a special effects company called Future General,” Dykstra says. “We’d finished up a couple of projects for Paramount, who owned that corporation, and we were on a hiatus situation. Gary Kurtz called one day and asked me to come and interview with him and George, to talk about some special effects on a movie called Star Wars. I didn’t know what the movie was then. As I remember, I just went in and we discussed it. George outlined the concept of the film primarily with regard to what the special effects would be—what he wanted to do and what he wanted to have happen. More than anything else, he wanted to get fluidity of motion, the ability to move the camera around so that you could create the illusion of actually photographing spaceships from a camera platform in space.”

To get his visual points across, Lucas was armed with the project he’d begun two years ago: the aerial battle short created from films on television. “At one point I had twenty to twenty-five hours’ worth of videotape,” he says. “I condensed that down to four or five hours, then I looked through that and condensed it down, shot by shot, to about an hour. We transferred about an hour to 16 mm film, and then I cut that down to about eight minutes. I would have the plane going from right to left, and a plane coming toward us and flying away from us, to see if the movement would generate excitement.

“We showed the film to John Dykstra when he started,” Lucas adds. “I described what I was going to do, and then I showed him the film and said this is what it’s going to look like.”

Two or three weeks after the interview Dykstra made a verbal commitment to do the film.

It was the meeting of two people whose goals overlapped: Lucas wanted to see his vision of a dogfight in space come to life, while Dykstra had the theoretical technical means to do it—if he was allowed to build a motion-control camera. “We had already gone over several problems,” Lucas says, “but I think the camera came out of the fact that John had wanted to build one. He had been playing around with it up here in San Francisco before, and he had played around with it at Trumbull’s for a while. He was anxious to actually build one, because it was an idea that John had had for quite a while and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to exploit that.”

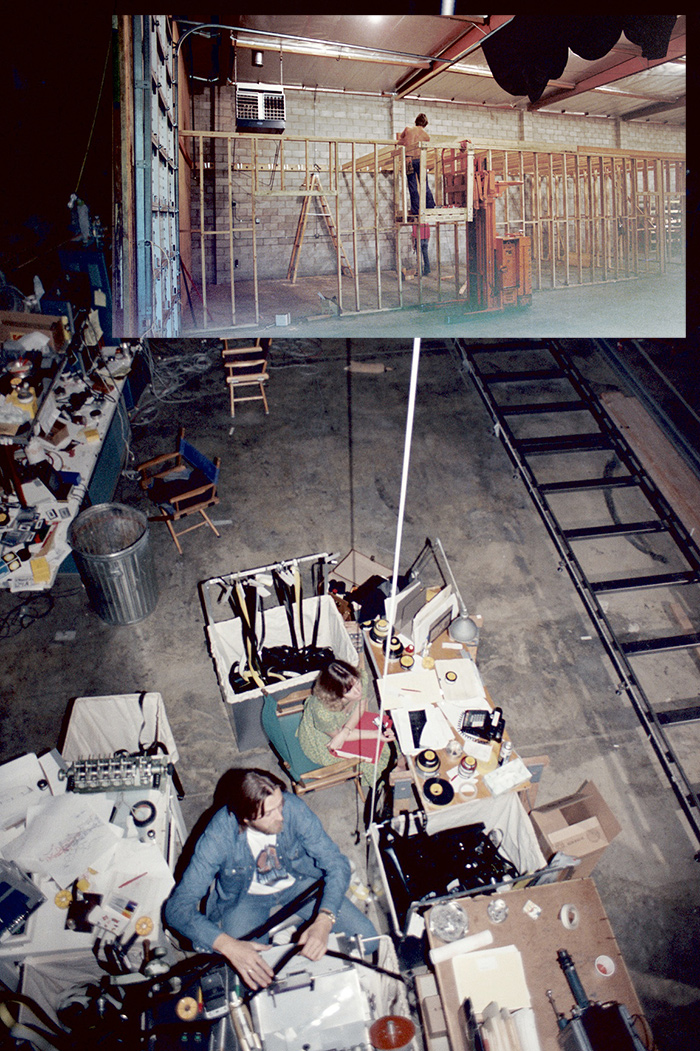

Richard (Dick) Alexander at work in the ILM machine shop.

John Dykstra reflects, sitting on the floor of the motion-control stage. “We’ve got milling machines, lathes, welders, everything you’d need in a general workshop,” Alexander says. On the floor of the shop and all over the ground floor were skid marks left over from when Dykstra took his dirt bike and tore around the vacant warehouse before the walls were up (inset).

Given Dykstra’s previous work in the Bay Area, Lucas had originally hoped to create the effects house in or near San Francisco. In late May 1975, however, Dykstra found what he considered the ideal location: an empty warehouse renting for $2,300 per month at 6842 Valjean Avenue in Van Nuys, a suburb just north of Los Angeles. He then persuaded Lucas that their technical needs forced them to be closer to the film development and color processing houses of Hollywood. Lucas reluctantly agreed, none too thrilled about being stretched even farther from his home base.

Richard Alexander, one of Dykstra’s colleagues from Silent Running, was one of the first people to come out and look at the place. Alexander brought with him Richard Edlund, a colleague from Bob Abel’s commercial house. “I came out and looked around,” Edlund says. “There wasn’t anything to see: It was an empty building. John asked me how much responsibility I wanted, and I said, ‘I don’t know. How about director of photography for the special effects? He said, ‘Fine. That’s the deal.’ ”

Edlund had already heard rumors about the project, which was scheduled to come out in two years’ time. “There were an estimated 350 shots, and it ended up being taken all around town before we got to it,” he says. By comparison, 2001 had about three years to do 205 shots—with eighteen months dedicated almost exclusively to those shots.

“Everybody said, ‘It just can’t be done in the time allotted,’ ” Edlund adds. “But John had sold George on the idea that we could build the system that could do it. So John arranged to get a studio together out in the valley and build the system, which started with a camera that would be able to photograph something repeatedly through programming and motors—that is, once you have the shot programmed, you can repeat that program over and over, as many times as you want, and then correlate information so that the shot can be done on a background for stars or a matte. So we proceeded to go ahead and build our systems. We were hideouts, in a way; we were not known people.”

Others had balked not only because of the time constraints, but also because of the very limited special effects budget. “John seemed to be the only one who was qualified and who was also interested in taking on the challenge,” Lucas says. “A lot of the people who were qualified didn’t want to have anything to do with it. They didn’t think it could be done. They thought it was impossible for the kind of money we were talking about.”

The situation hadn’t been helped when the studio had taken photos of the models Cantwell had built and authorized an independent special effects budget estimate. “I think they budgeted on the outside,” Lucas adds. “Fox went to Van Der Veer [a special effects house] and a few of those places, and asked them, given 350 shots and the storyboards, how much do you think this would cost? The estimates came in and averaged out to around $7 million. We were saying at that time that we would do it for $2.3 million, but then Twentieth Century-Fox cut it down to $1.5 million. They just assumed that it would all get done somehow. They just figured that we could do it for a million and a half, and that it was our problem, not theirs—because they didn’t think we could even build the models for a million and a half, let alone all the special effects.”

Again, a comparison with 2001 is useful: Its 205 special effects shots cost $6.5 million out of a total budget of $10.5 million, in 1967 dollars. Given the intervening eight years of inflation, it’s no wonder that nearly no one would go anywhere near what had to resemble an impending train wreck of a film. Moreover, in Hollywood at that time, special effects films were considered expensive without being guaranteed box office. Fox was thus still dragging its feet, given the ever-present lack of a contract, and, after slashing its budget, committed funds to Lucas’s special effects start-up only theoretically.

“When it came down to the real crunch,” Lucas says, “when we needed the half million dollars to get going, because we’d already committed the money, they delayed for about four or five weeks. So I had to put up the cash.”

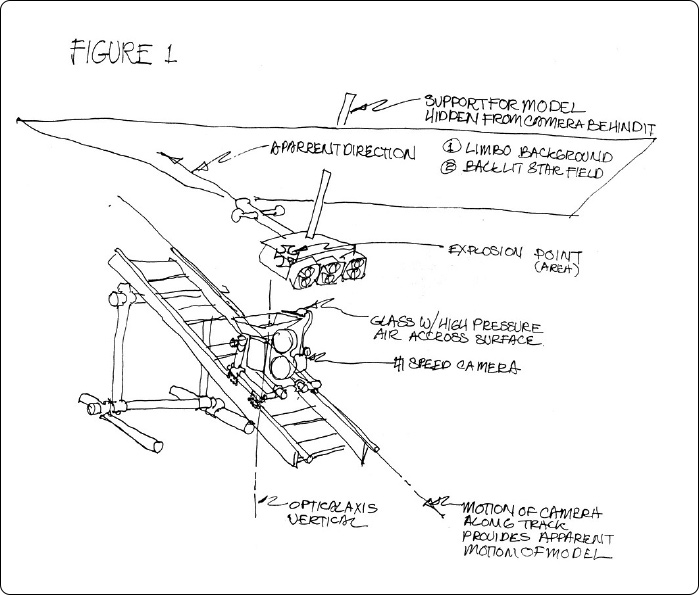

Before ILM was up and running, the special effects house created estimates for the opening sequence. In this drawing Cantwell’s rebel ship is placed on a rented high-speed camera for shot 3. It was calculated that these four seconds of screen time would take one and a half weeks to rig and three days to shoot, with two camera passes, for a total of two weeks and $15,017. (Note that the rebel ship has front gun turrets, unlike the pirate ship.)

At the moment of incorporating his special effects company, Lucas needed a name. “It just popped into my head,” he says. “We were sitting in an industrial park and using light to create magic. That’s what they were going to do.” Industrial Light & Magic was born.

But before any work could occur at the newly christened establishment, the right people had to be hired and the warehouse had to be converted into shops and offices. Dykstra worked out of a little back office he had at Universal and made phone calls. One of the first went to model builder Grant McCune. “I decided to do it,” McCune recalls, “and we started out with almost no experience in building models in this quantity or this type.”

Graduating with a degree in biology and then training as a laboratory technician, McCune changed careers and met Dykstra in 1969. Later they worked on the television movie Strange New World (1975), while their mutual interest in miniatures meant they flew gliders, sailed model boats, and raced model cars together. “I started on day one. It was June 1 of ’75,” McCune says.

Other key technicians hired that month were Jerry Greenwood, who would help build the special mechanical equipment; Richard Alexander, who began the machine work, having apprenticed seven years in England at an optical instrument company; Bob Shepherd as the facility’s production manager; Al Miller, the electronics designer; Don Trumbull, father of Doug Trumbull, who commenced work on the camera system, drafting the blueprints; Bill Shourt and Jamie Shourt, who joined McCune in the model shop, specializing in mechanical design; and Edlund, who started the camera department. They all knew one another and had worked together before: Richard (Dick) Alexander had once shared an apartment with John Dykstra for six months; Shepherd and Dykstra had worked on Silent Running; the Shourts, Edlund, and Alexander had all worked for Bob Abel.

“All of us had worked with each other and were pretty good friends,” McCune says, “and we talked to each other on a weekly basis just as friends. When John put the crew together, he put it together instantaneously, at least the nucleus of it.”

Robbie Blalack and Adam Beckett were the last two of the initial crew hired, in July 1975. “John called me up and said, ‘I’ve got the effects on Star Wars, I want to talk to you about putting together the optical department,’ ” Blalack says. He started immediately. Beckett began the animation and rotoscope setup shortly thereafter.

While the project alone was interesting, even at that time Lucas already had a reputation as an innovative filmmaker. “The idea of working with George Lucas was the most exciting thing to me,” Edlund says. “Because I’d really liked THX 1138. I loved his approach and his attitude.” Edlund had worked mostly in 1960s television up till then: The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone, and Star Trek. “I teleported hundreds of guys.” A number of times he even played Thing—a disembodied human hand—on The Addams Family.

Under the aegis of this skeleton crew, the downstairs of the Van Nuys warehouse was quickly transformed into an optical department big enough for two optical printers, a rotoscope department, two shooting stages, a model shop, a machine shop, a wood shop, and offices—Dykstra’s sitting opposite Shepherd’s. “We just walked around putting tape on the floors and figuring out general areas,” Shepherd says. “Next we made drawings for the spaces that were required and started building them.”

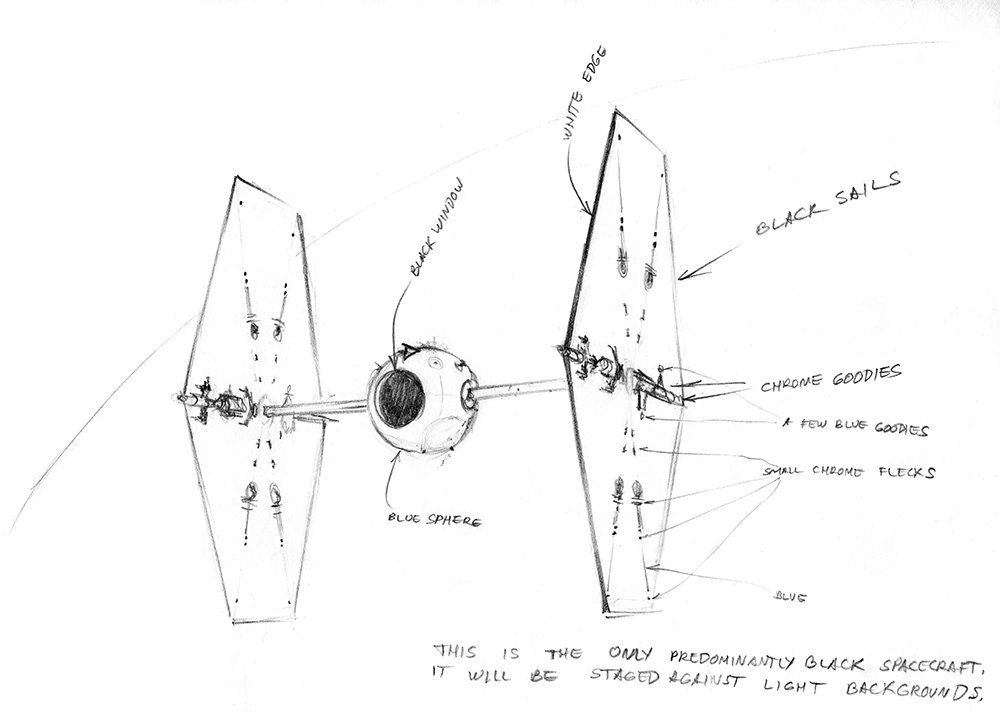

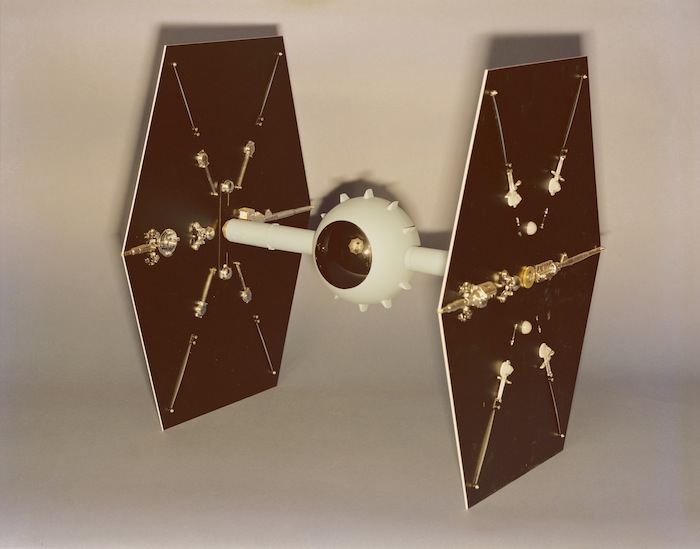

Sketch of a TIE fighter by Cantwell

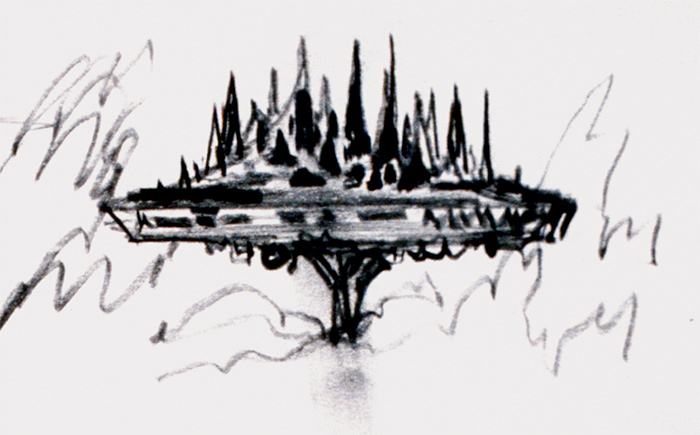

Thumbnail painting by McQuarrie

McQuarrie and Cantwell continued to complement each other. The latter’s sketch of a TIE fighter was implemented by the former into an earlier thumbnail painting, and then added to an already finished painting. Throughout production, McQuarrie would update illustrations as new vehicles were designed or enhanced.

“The TIE has different technology,” Cantwell says. “It has no regular engines and it has just this ball in the middle and the two solar fins. But especially you can’t tell how Darth Vader gets in; it’s something alien.”

Upstairs on the smaller second floor were the animation, editorial, and art departments, along with a screening room—though at the beginning these rooms were empty. “My original vision of this place included a swimming pool,” Dykstra says, laughing. “Seriously, it had to have high ceilings and it had to be far enough out of the central Hollywood complex; otherwise you end up with people constantly dropping in. People find out that you’re doing special effects, and they want a job or to build models, so you end up with a guard at the door, which makes it really a crummy situation. So we wanted a nondescript location, while still being close enough to the freeway and the lab processors in downtown Los Angeles. And we do have high ceilings, twenty-four feet to the bay, which means that we can put lights up real high to get particular angles, or we can put the camera up on the ceiling to get a wide shot looking down.

“We’ve got twelve thousand square feet divided between the two stages,” Dykstra adds, “but we ended up having to modify the building incredibly. Jim Hanna is an amazingly nice landlord. He said, ‘Well, whatever you want to change, you’ve got to put it back eventually, but that’s okay.’ He was really loose about us hanging fixtures back there or cutting something in half or taking the floors up.”

“As soon as we got the physical plant built so that we could do work, which took about six weeks, to actually get some walls up, there was a whole big move-in period,” Shepherd says. “Everybody was new to their job and they were setting up their own departments. We tried to give everybody what they wanted: desks, tables, a chair, their own pencil sharpener. Then three main things got going simultaneously. One was the generation of the models, the second was the camera system, and third was the optical compositing system.”

It was up to the small band to figure out what equipment was required for these three main areas, to estimate how much time it would take to build new equipment or modify preexisting equipment, and to hire the additional people required to do it all. “It was really overwhelming,” Dykstra concludes, “because I sat at a little desk and figured out how to spend $1.28 million.”

“We were all sitting down arguing about what had to be done,” Richard Alexander says, “and Don Trumbull would wheel out his sheets of brown paper and we’d all start scribbling on them, and writing this and that. There was no real one person deciding anything, which was kind of nice.”

During these embryonic brainstorming sessions, while all contributed, each was aware of everyone else’s specialties. “Don answers all the mechanical problems,” McCune says. “While John dreams about 8-perf with 4 pins to pull it across at 50 frames per second with perfect registration.”

“There’s a significant difference between coming up with a good idea,” Dykstra agrees, “and executing it.”

“We had a lot of conferences about optical and camera equipment,” McCune adds. “But it was only six weeks before we were starting to produce models and the machine shop was starting to produce mechanical devices. We had a lot of conferences with George; a lot of them went through John from George and back to me. He knew what he wanted.”

Industrial Light & Magic, or ILM, at its birth seemed to have the two elements necessary for creativity: a certain amount of chaos and a certain amount of money. After their first three weeks of existence in June, Lucas had already shelled out $87,921. While those same two elements, in differing quantities, would combine to create other situations, at the beginning everyone was enthusiastic. “I thought that at some point, things have got to change—the people who have ideas to do things should be allowed to do them,” Edlund says. “It was providential to me that Star Wars came along, because it was the response to that dream. We all got together, in a highly unorthodox way, in this little warehouse out in Van Nuys.”

In the spring of 1975, simultaneous with the beginnings of ILM, Gary Kurtz flew with Francis Ford Coppola to the Florida Everglades, the former scouting for a suitable jungle planet, the latter a suitable Vietnam for Apocalypse Now, which was beginning anew to attract studio interest. Kurtz then traveled alone to Olympic National Forest in Washington and “trudged around for three weeks looking at the rain forest.” The national park was soon rejected, though, because it had too many inherent restrictions. He then went to Toronto to look at the IMAX system. “They were willing to pick up the tab between that and regular 35 millimeter,” he explains, “which could have been half a million dollars. But converting theaters is difficult, and optical effects were next to impossible in that format. Special equipment would have had to be built. It was just beyond us to seriously consider it.” Not having a production designer yet, Kurtz then flew to Calgary, Canada, to talk with Anthony Masters, who was working on Robert Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976).

Kurtz then rejoined Lucas, and the two traveled to Mexico City during the July 4 weekend. This was actually their second trip, having been to Guaymas, Mexico, the previous spring. Lucas’s friends the Huycks had been and were still on location down south working on Lucky Lady (1975)—another Fox film, which would remain strangely tangential to The Star Wars throughout its production.

Lucas went primarily to see how a big-budget movie was being made and to talk to potential department heads. He had toured the sets on the previous visit and had probably witnessed some of the film’s problems: Location shooting on boats had caused many complications; many of the cast and crew had become ill, including the film’s star, Liza Minnelli; and one person had died. By July they were just finishing, so Lucas was able to renew talks with Lucky Lady’s cameraman Geoffrey Unsworth, and spent Sunday morning chatting with its veteran production designer John Barry.

Barry had worked as a draftsman on Cleopatra (1963). Kubrick had offered Barry the production designer job on Napoleon, which he worked on for one whole week (the film was never made). Barry moved on to become production designer on Kelly’s Heroes (1970) before collaborating again with Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange (1971). Years before, he’d been on the TV series Danger Man (1964–1966), where he’d met its art director, Elliot Scott, who afterward took on Barry as his assistant—and who had suggested Barry to Lucas back in England.

“George came to see me in Mexico,” John Barry says, “and decided that perhaps I’d be the one to do it. I have just enough experience to be able to cope with the problems, and just enough inexperience so I should take it on. I think anybody with more experience would have just said, ‘I don’t think I can do it in that amount of time.’ ”

Indeed, the clock was ticking, with principal photography tentatively planned for February 1976, less than a year away. Having read the script, Barry said that he would need “seven months minimum”—exactly the time remaining—to design and build the sets.

“I knew we were going to have an incredibly difficult job,” Lucas says. “Just the sheer size of the thing was going to be difficult, and I wanted somebody who I felt was really down to earth and solid and could get the job done—without costing me ten times what I thought it was going to cost me. He was doing a good job on Lucky Lady, and just talking with him I got an impression. You look at the films he’s done and you listen to people who have worked with him. Based on those things, you make your decision.”

Conversations went well with Unsworth, too, as he understood the look Lucas was after. “Geoffrey Unsworth was very flexible,” Lucas adds. “His style was so much different on every movie, so I thought he would be great, easy to work with, and I really liked what he had done. Also I wanted to give the film a very diffused look, similar to what he had done on Murder on the Orient Express [1974]. It had that fairy-tale quality about it.

“So I decided I wanted to go with Geoffrey Unsworth. He said, ‘Okay.’ And I wanted John Barry to be the art director, and he said, ‘Okay,’ and then we got going.”

One of those who had fallen ill during the Lucky Lady shoot was set decorator Roger Christian, but he became the third person of that production team hired by Lucas for The Star Wars. After Lucas and Kurtz returned home, on his way back to London, John Barry flew up to San Francisco for more talks on how to do the necessary within the $1 million budget that had been allocated for the sets.

Lucas never acquired an office on the Fox lot “because he believed politically, and he was right, that you don’t want to be on the same lot as the studio, because they can invade your space and give you a hard time,” explains Charles Lippincott, who had been hired to handle the film’s marketing and merchandising. “And Fox did give me a hard time because I was the major person working out of that office, and they really put the screws to me. But they couldn’t do anything, ’cause George was at Universal—it was a very smart idea.”

Instead Lucas would occasionally make use of Kurtz’s office on the Universal lot, where Steven Spielberg also had an office in one of the bungalows (Kurtz’s bungalow was 426). Lucas and Spielberg had met back in the late 1960s, when the latter had been amazed by the former’s THX 1138.4EB. They had since become good friends, so when Spielberg was back from Martha’s Vineyard and in postproduction on Jaws (1975), Lucas naturally went around from time to time to see how things were developing. Unusually for most directors, but standard for Lucas, he had already been thinking about the soundtrack for The Star Wars, and was leaning toward a classical, romantic one. Spielberg suggested the fellow who had just finished composing the soundtrack for Jaws; Lucas got to hear some of it and was impressed.

“Steven said, ‘I worked with this guy and he’s great!’ ” Lucas remembers.

Thus in the spring of 1975 Lucas met with perhaps the most key member of his team: composer John Williams. “Steven Spielberg introduced me to George,” Williams says, “and told me about Star Wars and George Lucas, and how much he admired him.”

Williams proceeded to read the script, but wouldn’t start actually composing for more than a year, as he had prior commitments to Alfred Hitchcock’s Family Plot (1976), Black Sunday (1977), and his own violin concerto.

Not only did Lucas start thinking about the music early on, he was also eager to start work on the sound effects and sound design of his film—to continue his tradition of innovative sound use as established by THX 1138 and American Graffiti, which had one of the first soundtracks specifically made for stereo. “Usually Walter Murch worked with me,” Lucas says. “He is a genius who I went to school with who had done the sound work in all my movies.” Murch had been preapproved in the deal memo—but as of July 1975 he was occupied elsewhere on a number of projects, including Julia (1977), and had committed to do The Black Stallion (1979). “So we decided to go to USC. We called the sound department and we asked Ken Miura, who is a friend of ours, ‘Who’s the next Walter Murch?’ And they sent us Ben Burtt.”

By May 1975 McQuarrie had finished his first round of paintings. On June 11, 1975, he completed work on The Star Wars logo. Lucas had supplied the artist with a page of American Graffiti stationery, saying that he wanted something similar to adorn the appropriate paraphernalia associated with his latest film. The artist’s first sketches reveal Han Solo (bottom left) and then Luke in his starpilot costume (bottom right), with his home planet in the background, posing like Han Solo in the Fantastic Five illustration. After completing the logo, McQuarrie went free-lance from June 27 to July 24.

“I’ve always collected sound effects,” Burtt says. “Since I was about seven years old, off the TV. As a teenager I used to go to the drive-in movies and reconnect the wires from the speaker to make direct recordings.”

Burtt’s professional career began the day Ken Miura called him. “I met with Gary and saw some of the paintings for Star Wars,” Burtt continues. “They wanted someone to come up with a voice for a creature called a Wookiee. Apparently a Wookiee was going to be an important character and they were concerned about getting some kind of voice for him before they started shooting. Gary said, ‘We’ve got this big sidekick, like a giant teddy bear, but he can be ferocious if he’s coming to the rescue; the rest of the time he’s like a big dog.’ The problem they had was that he didn’t speak English. He wasn’t going to speak an intelligible language; he had to sound like an animal, but we had to understand his emotions. I got a look at the script after a month and met with George in August, and at that point it became evident that they really wanted someone to build a whole library of material.”

“Ben started collecting sounds before we even started shooting the film,” Lucas says. “I described what I wanted the spaceships to sound like and what I wanted from the laser swords, and I said, ‘Collect weird, strange sounds. Go to the zoo, collect all the animal sounds. Go to transportation places.’ We had several categories that I wanted him to do. One was animals; another was all kinds of dialects and dialogues. And one was just to collect any kind of sound that could be used for a laser gun—weird zaps and cracks and things like that.”

“They sent me down some equipment from Zoetrope,” says Burtt, picking up the story. “A Nagra and some microphones, and I just started gathering sounds. George thought that bear sounds might be the right direction to take for the Wookiee, so that initiated the search for all kinds of bear material. I also broke down the script in terms of every possible thing that might make sound: laser guns, laser swords, the landspeeder, the various spaceships. I went through and saw how many different sets were in the film. So I made a big notebook with that stuff divided up, and I kept a record of ideas that might apply to any one of those areas, and then I’d go out and look for them.

In Mexico, DP Geoffrey Unsworth, Willard Huyck (middle), and Lucas talk while on a boat, as much of Lucky Lady—the production they were visiting—was being shot on the water.

Another movie shot on the water was Jaws, whose production offices were at Universal Studios, where Lucas and friends visited Spielberg: (from left) Hal Barwood, Gloria Huyck, Lucas, Kurtz, Colin Cantwell, Willard Huyck.

“I recorded the original sounds on the Nagra IV-S, their only stereo model [released in 1971],” Ben Burtt says (recording a bear named Pooh), “and I played with it on ¼-inch tape-that is, I played it into an ARP synthesizer that Coppola happened to have. I also had the use of a Moog and a Harmonizer, which is an Eventide piece of equipment, a device with which you can play a sound, and then raise or lower the pitch without changing the time reference. So I could play a voice, and I could play it high-pitched or low-pitched while retaining the same rapidity of speed. I had a Urei dip filter, which is just a fancy filter for taking out unwanted material, and I had a graphic equalizer.”

Lucas works with McQuarrie.

“In the early stages I spent a lot of time hunting down animal recordings. I listened to all the various material I could get out of libraries in town, and all the various studios. Occidental College has a huge collection of bird sounds from around the world. I went there and spent several days listening to everything they had. But we wanted the sounds to be original, so I also rented animals; I went to people that trained animals for movies, who have ranches, who have bears and elephants and camels. I’d go out in the desert where it was quiet and stand around with the recorders.”

Presumably during short stints at Medway and on the road, Lucas developed his third draft from the May 1 Story Synopsis and notes. At Park Way, Bunny Alsup had joined the group in the restored Victorian house. “The environment was great fun because we were a small, intimate group and were all young fledgling filmmakers,” she says. “George was writing Star Wars. He’d turn the pages over to me and I’d type them. Star Wars was a much more difficult script for me to type [than American Graffiti] because it was like a foreign language. Science fiction was foreign to me and he had many words I’d never heard of in my life. Spelling the names was also a challenge, because he was inconsistent in how he spelled them.”

The pages Lucas handed off were as usual prefigured by his notes: “Robots and rebel troops listen as the weird sounds of stormtroopers are heard on the top of the ship … Sith rips rebel’s arm off at end of battle … only seven Sith—one in each sector … small ships avoid deflector shields/tractor beams.”

Another note falls under the title, “New scenes: Luke sees space battle.” Luke’s emergence as the hero of the film was one reason Lucas made a decision to write additional scenes on Utapau, which show Luke observing the opening battle in the sky and then talking with friends. It was Lucas’s own friends Matt Robbins and Hal Barwood who had provided another reason: They thought that Luke needed to appear earlier in the film, to establish a link with impatient audiences. “Francis had read the script and given me his ideas,” Lucas says. “Steven Spielberg had read the script. All of my friends had read the script. Everybody who had read the script gave their input about what they thought was good, or bad, or indifferent; what worked, what didn’t work—and what was confusing. I would do the same on their scripts. Matt and Hal thought the first half hour of the film would be better if Luke was intercut with the robots, so I did that.”

And while some characters were cut out completely, two who were absent from the second draft return. Leia replaces Deak, becoming the unnamed princess of the Story Synopsis. She is reintroduced at the film’s outset, as she was in the treatment, instead of halfway through on Alderaan. The old man also acquires a name: General Ben Kenobi, who becomes the wizened old man/Jedi and occupies the role of mentor, originally filled by General Skywalker in the rough and first draft. He trains Luke in the ways of the Force, becoming an important foil in the student’s voyage of self-discovery. Perhaps due to Lucas’s appreciation of Campbell’s analysis of mythology, Luke is more of a loner; he is stripped of his brothers and cousins—and now his father is a dead Jedi.

In late July and early August, McQuarrie returned to work on The Star Wars, doing costume designs. One of them is a first look at General Ben Kenobi. The sleeveless shirt recalls the garb of a samurai from one of Kurosawa’s films.

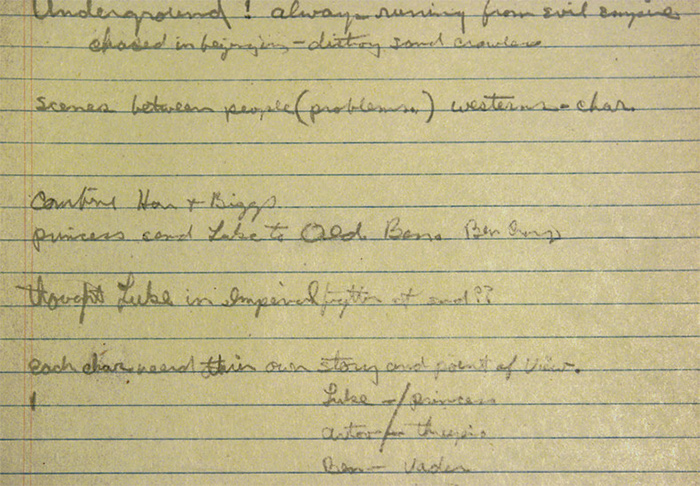

Lucas’s notes from the time indicate major plot revisions—“princess send Luke to Old Ben”—and ideas that didn’t quite make it into the third draft: “combine Han and Biggs.”

Luke’s voyage is also more defined in the third-draft notes, as it becomes more related to the Force, which he learns about in specific stages: “1) Luke learns about Force (in desert); 2) Luke tries to experience Force (in ship); 3) Luke becomes a man of the Force (Alderaan); 4) Ben explains Luke’s experience (in ship); 5) Luke with crystal struggles with Force (on Yavin).”

“I have come to the conclusion that there is a force larger than the individual,” Lucas says. “It is controlled by the individuals, and it controls them. All I’m saying is that the pure soul is connected to a larger energy field that you would begin to understand if you went all the way back and saw yourself in your purest sense.”

Another note reads, “Learn about the Force—all around us in every living creature.” It is defined in similar terms by Kenobi in the third draft. As the hero’s journey becomes more linked to the Force, the Kiber Crystal’s importance naturally fades. Primarily a “MacGuffin”—a plot element that Alfred Hitchcock defined as an item of no emotional significance, but which keeps the story moving—the crystal also has a new rival in the plans to the Death Star. It thus moves far into the background, as the third draft has little space for two MacGuffins.

The crystal, however, is still part of the aerial attack on the Death Star—the last element to undergo structural alterations. “Between the second and third drafts, Luke stopped on the surface on the Death Star,” Lucas says. “He and Artoo had to go and take the bomb by hand, open up the little hatch, and drop the bomb in it—then they had fifteen seconds or something to get off the surface before the thing blew up—but as they were going back to the ship, Darth Vader arrived. So Luke and Vader had a big swordfight. Luke finally overcame Vader and then jumped in the ship and took off. But in trying to intercut the dogfight with the old-fashioned swordfight, I realized that the film would have just stopped dead. It was too risky.

“I feel that I’m fairly decent at construction, not necessarily plot, but construction,” Lucas says of these changes. “Neither Graffiti nor THX had plots. I’m not really interested in plots. That’s one of the problems I’ve had with this movie—it’s a plotted movie, and I find plots boring because they’re so mechanical. You go from here to there, and once you know what’s going to happen, that’s it. And I just am not enthralled with that kind of action. I’m much more into the scenes and the nuances of what’s going on. I find that fascinating.”

Lucas wrote notes on Luke’s cognitive progression in relation to the Force, followed by a list of words formulating key ideas for the film.

“I had worked on Star Wars for about two years,” Lucas says, “and we were starting preproduction. Francis had finished The Godfather II (1974) and he was saying, ‘I’m going to finance movies myself—we don’t have to worry about anybody, so come and do this movie.’ I had a choice: I had put four years into Apocalypse Now, and two years into Star Wars—but something inside said, ‘Do Star Wars and then try to do Apocalypse Now.’ So I said that to Francis, and he said, ‘We really have to do it right now; I’ve got the money, and I think this is the time for this film to come out.’ So I said, ‘Why don’t you do it then?’ So he went off and did it.”

What must have been a difficult choice was made somewhat easier by the reaction Lucas was still experiencing to American Graffiti. “Part of my decision was based on the fan mail I had gotten from Graffiti,” he says. “I seemed to have struck a chord with kids; I had found something they were missing. After the 1960s, it was the end of the protest movement and the whole phenomenon. The drugs were really getting bad, kids were dying, and there was nothing left to protest. But Graffiti just said, Get into your car and go chase some girls. That’s all you have to do. A lot of kids didn’t even know that, so we kept getting all these letters from all over the country saying, ‘Wow, this is great, I really found myself.’ It seemed to straighten a lot of them out.

“I also realized that, whereas THX had a very pessimistic point of view, American Graffiti said essentially that we were all very good. Apocalypse Now was very much like THX, and Star Wars was very much like American Graffiti, so I thought it’d be more beneficial for kids,” he adds. “When I started the film, ten- and twelve-year-olds didn’t really have the fantasy life that we’d had. I’d been around kids and they talked about Kojak and The Six Million Dollar Man, but they didn’t have any real vision of all the incredible and crazy and wonderful things that we had when we were young—pirate movies and Westerns and all that. When I mentioned to kids, like Francis’s sons who are eleven and eight, that I was doing a space film, they went crazy. In a way I was using Francis’s kids as models, because I’m around them the most. They’re the ones who I talked to about the story. I know what they like.”

Optical department supervisor Robbie Blalack poses within an optical printer at ILM.