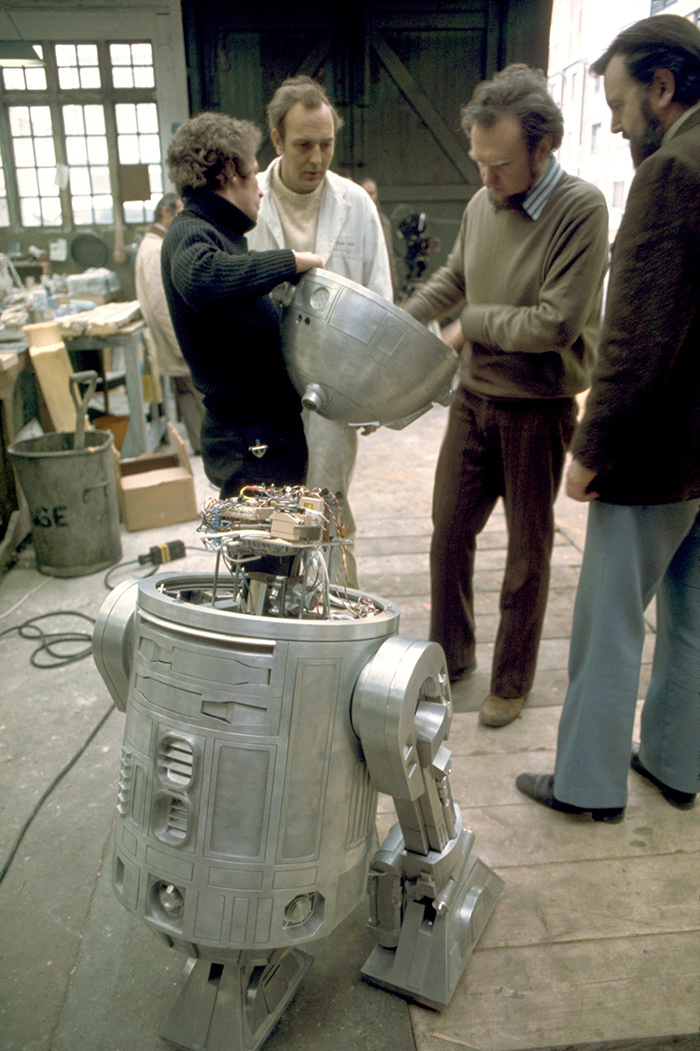

August 1975 saw action in England, with Lucas and Kurtz flying over from the States for the first of many brief preproduction stays. The latter arrived first and continued to review studios; at this point Pinewood was the front-runner. On August 1 production designer John Barry officially started, renting space at Lee Electrics in London. His first assignments were to build a landspeeder and to work on the robots with John Stears. They began by making a cardboard mock-up of R2-D2 based on the McQuarrie paintings. Kenny Baker was hired to be the man inside the droid.

“I got the job right away,” says Baker, who came to the interview with his longtime cabaret partner, Jack Purvis. “I said, ‘I can’t just walk into a movie and leave my partner stranded.’ They said, ‘Well, we have plenty of work for Jack,’ and they made him head Jawa.”

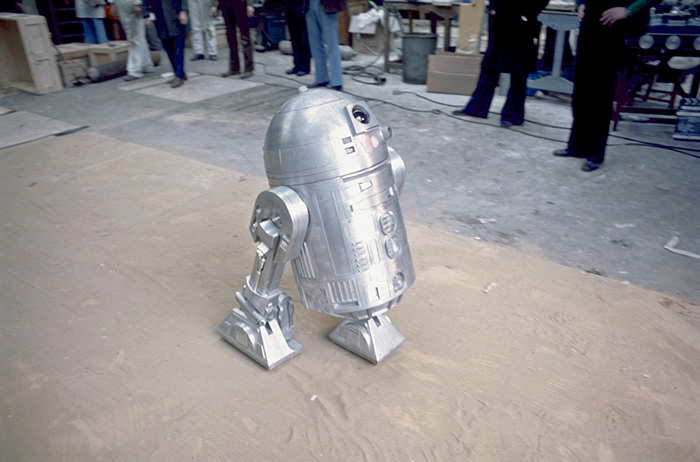

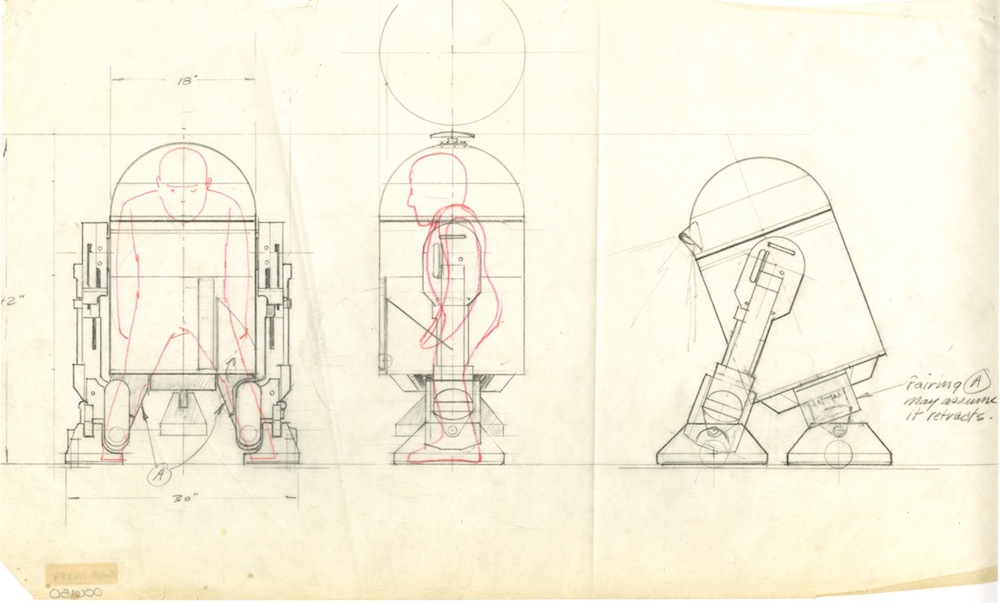

“We had to start with a tiny man to go in Artoo,” Barry says. “He’s only forty inches, Kenny, and very strong, fortunately, because it’s very hard to move. So we figured out where it was going to hurt him, and all the techniques around the boots. He’s got these specially made little boots that lace up tightly and hold his—the robot’s—boot firmly to his leg so that it moves as one. Then the harness that holds the body onto Kenny was quite important.”

“It just wasn’t very comfortable,” Baker says. “They had screws going through the robot’s head that stuck into my head.”

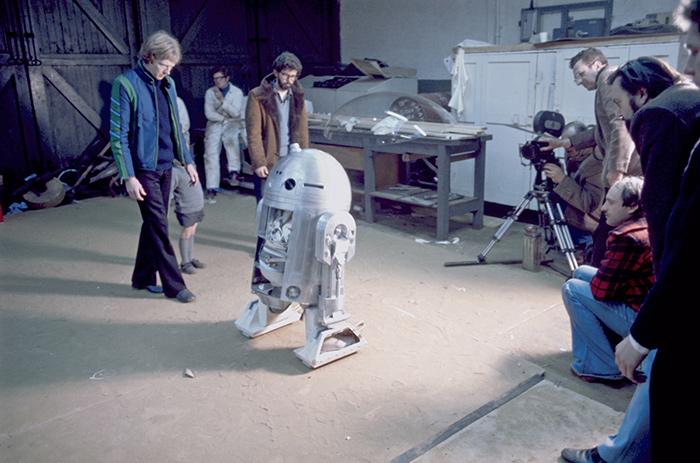

“When George came back to England around the middle of August, I said, ‘Look! What about that?’ ” Barry says. “And little Kenny—he’s a wonderful little man, I must say, marvelous—he came around the corner in the studio in this little wooden dust bin, a sort of mock-out trash can. He’s waddling across the floor, and George says at once, ‘That’ll work.’ ”

“We met Kenny and he was a good possibility for one of the robots,” John Stears says. “Working with Kenny in the early days, we made up mock-ups, and we could see exactly what he could do and what he couldn’t do, how fast he could move, and so on. Therefore we got into a mechanical situation, because this thing has to do things that Kenny was not physically capable of doing.”

Once a mechanical R2-D2 was deemed necessary for some shots, Stears spent a lot of time at a hospital where limbs were made for amputees; he visited atomic research facilities to study how the mechanical arms worked, even talking with a robotics professor “who thought I was crazy,” Stears admits. “With that knowledge, I once again worked out what was possible, spoke to George about it, and we tailored the actual mechanical answer.”

“Maybe it’s only over lunch, but all the time you’re talking about, ‘How about if we do this, how about if we do that?’ ” Barry says. “The outside of the robot we conceived of with lots of little panels, doors, all over it—so we know that if ever we need another arm or another antenna, we can say it is right behind that panel.”

As the workload increased, the production art department slowly staffed up and soon had about twenty-five to thirty people. Among them, John Barry supervised the efforts of Harry Lange, another of the class of 2001, who was designing control panels. “He’s got a tremendous eye for that sort of thing,” Barry says. “He really produces amazing things out of some amazing materials. The trick of it all was to come back with an eggbeater and half a vacuum cleaner, and suddenly whip up the most amazing control panels.” Another new hire, Liz Moore, concentrated on the landspeeder and C-3PO fabrication.

Back in 1973 Kurtz had spoken to a local production supervisor named Robert Watts, who was preparing The Wilby Conspiracy (1975) for location shooting in Kenya, and had asked him to send over his résumé. In April 1975 Watts had received a call from Peter Beale, the Fox representative in London, who asked Watts to meet Kurtz in Soho Square on May 1. Kurtz then contacted him in June to speak further about the project—and now Watts was undergoing the last part of his lengthy interview process by meeting with Lucas.

“I reckon I was about ten years old when I first went on a film set,” Watts says, “and it was about that age that I decided it was the life for me.” His grandfather had worked as a script writer at Ealing Studios, where Watts obtained his first job as assistant office boy in 1960, afterward working his way up to third assistant director and then production manager on films such as Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965), Thunderball (1965), and You Only Live Twice (1967).

Set dresser Roger Christian remembers the beginnings of R2-D2. (Interview by J. W.

Rinzler, 2012)

(2:37)

In addition to interviewing more potential department heads, Lucas had important conversations with John Barry, who says, “I talked with George very much. He showed tremendous interest in the sets, so we knew very much what he wanted to do and where he wanted to be. George really wants to be involved in everything on the movie, whereas sometimes with a director you have the opposite problem. My personal taste leans more toward Barbarella [campy sci-fi film, 1968], which George didn’t want to do. He wants to make The Star Wars look like it’s shot on location on your average, everyday Death Star or Mos Eisley spaceport—which I think is a very valid point.

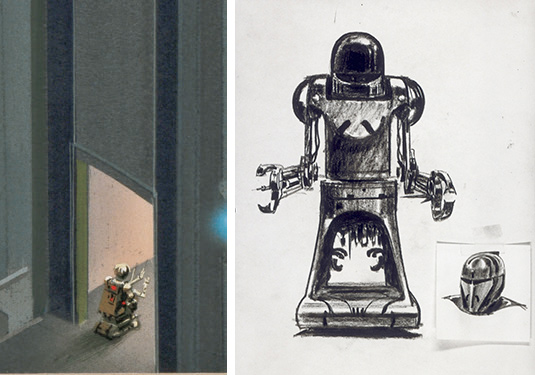

Kenny Baker was hired to be R2-D2, here shown in unpainted prototype form.

Lucas was satisfied enough at this point to pose with the robot and then give the photo to Ralph McQuarrie (courtesy of Ralph McQuarrie).

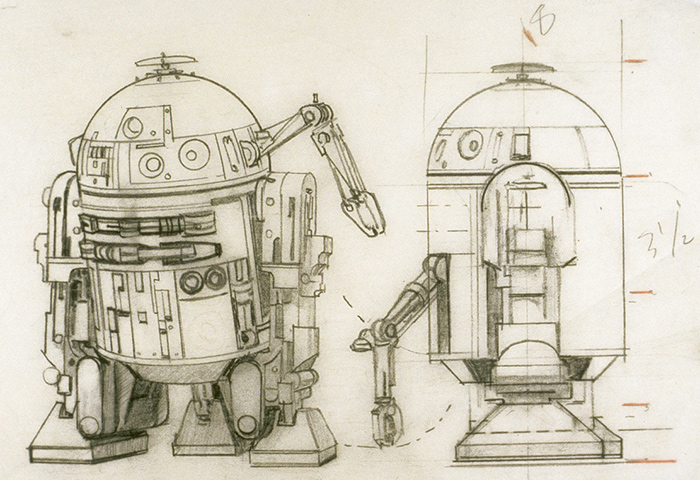

Ralph McQuarrie’s sketch of R2-D2’s inner workings had served as a conceptual guide.

A McQuarrie drawing indicates how a little person might fit inside the R2-D2 shell in order to operate the droid’s “legs.”

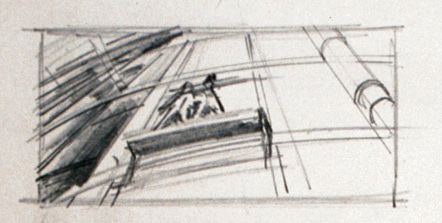

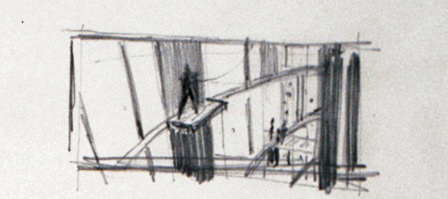

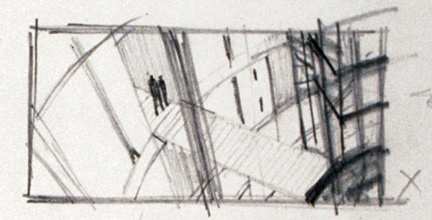

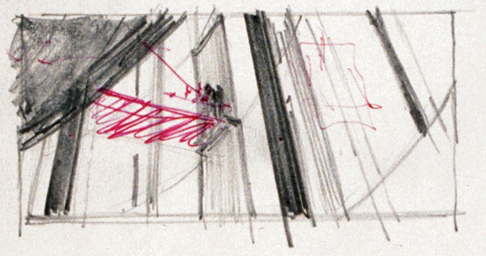

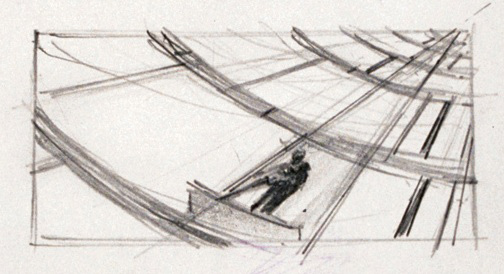

“Lash La Rue scene—Luke vaults over space left by retractable bridge” was McQuarrie’s title for his November 21, 1975, painting that visualized John Barry’s idea of late August

Preparatory sketches for “Lash La Rue scene—Luke vaults over space left by retractable bridge”.

Around the same time McQuarrie finished the Alderaan interior.

His sketch of a robot was for a detail in the bottom left-hand corner of the painting.

“The eighth illustration is the elevator scene, which was just the result of a little pencil sketch I did,” McQuarrie says. “We didn’t talk very much about how the elevator should be; George just said there would be a row of elevators and Luke, Han, and Chewbacca would have to come to them and stand there. So I decided to make them individual tubes rather than just open doors, just so they would be different. This big canyon wall was part of that Lash La Rue scene, where Luke has to jump across.”

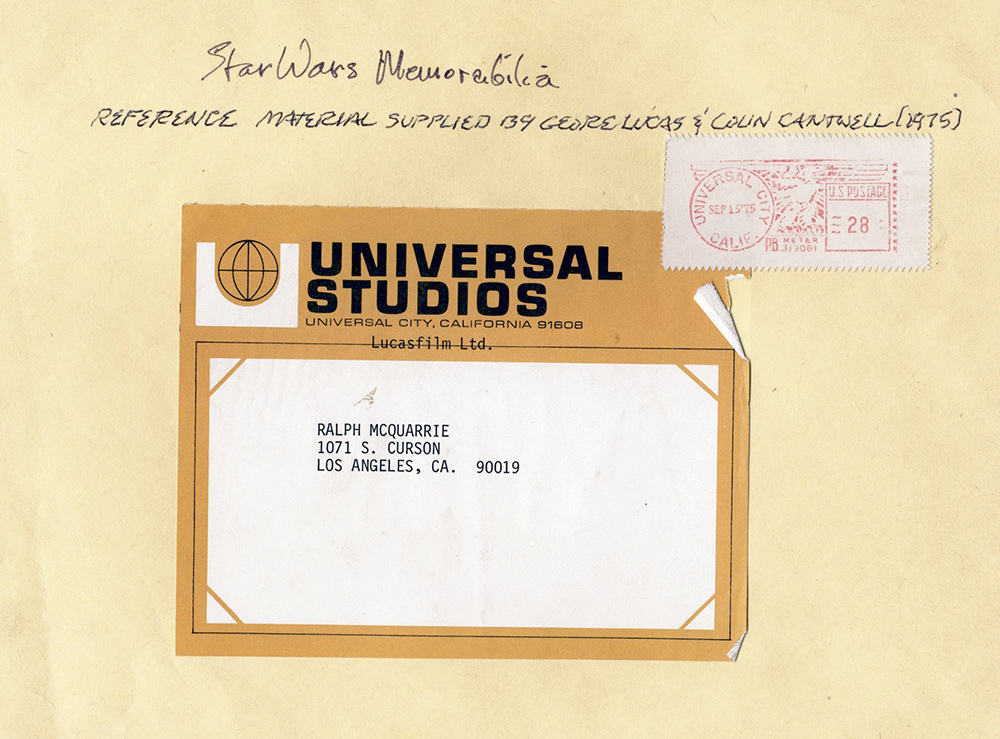

An envelope was sent to McQuarrie from Kurtz’s Universal Studios office in September 1975 and was used by the artist to store reference material given to him by Lucas.

“The thing is to design the sets simultaneously,” he adds, “knowing how you’re going to turn one into the next, because another area of responsibility is the budget—which, in this case, is a large percentage of the overall budget, in that there’s not a large number of very expensive actors.”

After talks in England, Barry flew to the States at roughly the same time as Lucas, who was preparing for the casting sessions. According to Ralph McQuarrie’s handwritten notes, John Barry arrived on August 20, 1975. The two met with Lucas to go over the artist’s paintings and discuss the sets in even more detail. “I had worked with Ralph McQuarrie while I was writing the script,” Lucas says, “and we designed certain things, but John was very willing to step in and say, ‘Yeah, these are good designs, let’s use those.’ He wasn’t hung up on the idea that everything would have to be his; he was very open to suggestions and he was very easy to work with. He also had a lot of good ideas of his own, adding creatively onto things without making it cost an enormous amount of money.”

One idea that Barry came up with at the time involved Luke and Leia escaping on Alderaan. “This was John Barry’s idea,” McQuarrie says, “to have this cliffhanger scene where the bridge retracts and Luke throws the little hook and swings her across. They call it the ‘Lash La Rue’ scene. This was after we had about three days of talks with John Barry, to introduce him to the project. I sat in because George thought I could do some sketches maybe while we were talking, but it was definitely established at that point that I was a sketch artist and not the art director, because John was going to be the art director.”

While Barry returned to England to supervise the burgeoning full-scale sets, and while ILM was still being set up as they built cameras and equipment, and while a contract with Fox was still outstanding, and while he was working on the fourth draft, Lucas began interviewing actors for The Star Wars in late August.

Having earned the director’s high opinion by casting American Graffiti, Fred Roos helped Lucas organize what was going to be a long process. “I was brought in to do some tests and give my opinion from time to time,” says Roos, who had built up his expertise by casting around forty low-budget movies.

“Fred didn’t get paid or anything,” Lucas says. “Fred is just a friend who is also a very good casting director who helped out as best he could. I asked his advice because I trust Fred’s opinion quite a bit; he’s very sharp about talent and casting. He’s a producer now and he really doesn’t cast anymore, but he got interested because I was working out of the American Zoetrope office in Los Angeles. Our offices were next door to each other, so he helped us. When I was in England, I could trust him to do tests and things, so he took some time out to do it. He really just did it as a friend.”

Like the two before it, Lucas’s third feature film was not a star vehicle, so he was going to have to devote enormous attention to the choice of his relatively unknown leads. “Deciding to cast unknowns was not a controversial decision,” Roos says, “because nobody cared at the time.”

Roos called casting director Dianne Crittenden in August 1975, and she eventually hired two assistants as the interviews multiplied. Crittenden may also have been recommended by the Huycks, who had worked with her on Lucky Lady, and she knew Coppola because they had attended Hofstra University at the same time. “I hadn’t read the script and I didn’t talk to George until right before we were ready to start,” Crittenden says. “It was just: ‘We need two young guys and a girl for this thing, and George will be here for three weeks.’ And I felt, Well, that will be fine. Then I read the script and found it fascinating, but I really didn’t know what it was about. I think I read it eight times before I finally got into it. But George knew what he wanted. He wanted Han to be a cowboy, the ‘James Dean’ character, but instead of a horse, he’s got a spaceship. Luke was a farmer. I said, ‘What do you mean, a farmer?’ And he said, ‘It’s a moon-farm or an interplanetary farm.’ George’s concept of the princess was an independent, strong one. Someone who was capable of leading her people, as opposed to some fragile fairy-tale kind of princess.”

With everyone ready, three weeks of casting began within the Zoetrope offices at the Goldwyn Studios in late August—and it was relentless, from 8 or 9 AM to 6 or 8:30 PM, as quickly as two people every five minutes, around 250 actors per day.

“I saw thousands of kids,” Lucas says. “I would see them for one minute, three minutes, five minutes. It gave me a physical idea of who they are, because you know about a person in one minute when you first meet them and they sit down. Your first impression of them is the same impression more or less as the audience’s when they meet them. The illusions can be much greater in theater because, with lighting and the distance, you are farther from the actor. You can fake things much easier. But with film, in a close-up, you are looking into somebody’s eyes—you are not only looking at the person as an actor, you are also looking at them as a human being. So I have to rely half on the human being and half on the actor. That’s been a prime requisite of anybody I use—I’ve hired very good actors who I’ve also felt could be that character in real life.”

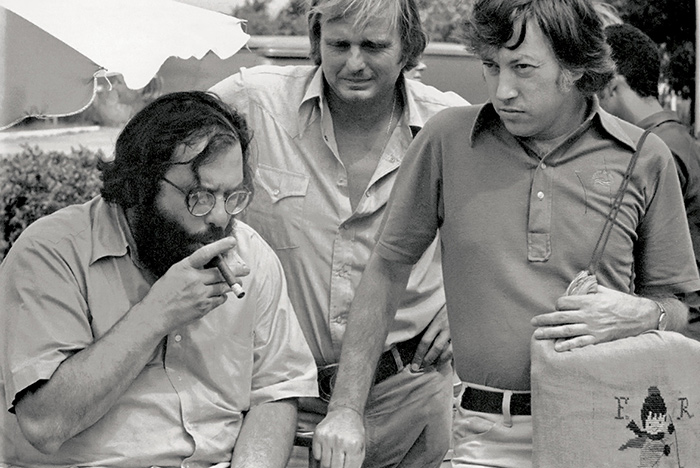

Francis Ford Coppola and Fred Roos (with initialed bag, “F. R.”) in the Dominican Republic shooting the Cuban sequence during the making of Godfather Part II, circa 1973.

Though the speed of the interviews made perfect sense to the low-key director, many of the young actors rolling through the doors were somewhat perplexed. “Generally, George would ask, ‘What have you been doing?’ ” Crittenden says. “And they would respond, ‘You mean, today, or with my life?’ George would say ‘Either.’ And you could see people start to squirm. They’d ask, ‘What’s this about anyway?’ And he’d say, ‘Well, we’re doing a science-fiction movie.’ I received hundreds of phone calls later with people asking, ‘What was I doing there? What happened?’

“George was looking for something very visual.”

“Brian De Palma called me to do Carrie [1976],” Crittenden says. “So I said, ‘I can’t because I’m working with George.’ And he said, ‘You’re working with George? He’s my friend and we’re looking for the same thing, so I’ll just sit in on this.’ So that’s what happened. But it added confusion to the process, since Brian is the one whose name more people knew. They’d sit there and they would say, ‘Oh, I just loved Hi, Mom! [1970].’ Which didn’t bother George; in fact it seemed to make him feel more comfortable, because it became easier for him to watch the performances. Afterward, the actor would leave and George would say, ‘A definite three,’ and Brian would say, ‘I’d give them a four,’ and it would go on like that.”

A mutual friend of De Palma and Lucas, editor Paul Hirsch heard about the casting sessions, which began as somewhat notorious—and have become legendary. “Brian was terrifying these new actors and actresses,” Hirsch says. “Brian told me George had the opening speech and he had the closing speech, and vice versa. They were seeing so many people that they got it down to less than a minute. If they knew they weren’t interested in the person they were seeing, no sooner had George finished the opening speech than Brian would launch into the closing speech.

McQuarrie’s early sketches of Han Solo may reflect Lucas’s changing idea of his appearance and costume, from a more savage pirate to a more debonair James Bond or gunslinger type.

Another McQuarrie sketch perhaps reflects Lucas’s fixed pursuit of Alec Guinness for the role of Ben Kenobi—the drawing, which is markedly different from earlier depictions, has the hairdo and look of Guinness. Written by Lucas in the corner are the words “Ben Kenobi.”

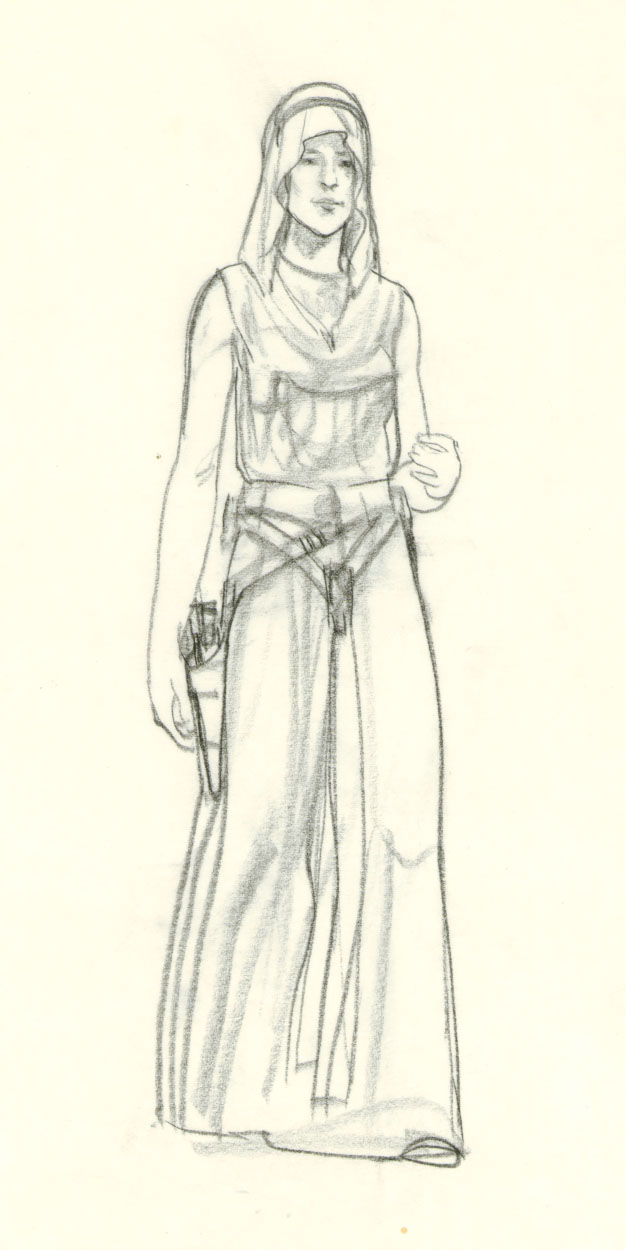

A McQuarrie costume concept sketch for Princess Leia, with blaster in holster.

“During that time, I called Brian and he said, ‘Listen just a second. George wants to speak to you.’ And George said he liked my work and maybe we’d work someday together,” Hirsch adds. “I remember saying, ‘Gee that’s really terrific.’ I had heard things about Star Wars and if there was really one film I wanted to work on, it was that one. Brian would go over and see the miniatures at ILM, and he would tell me that he was envious of George. Brian was doing this movie with girls slamming doors and George was having all this fun making models and building things.”

“Brian and I are very good friends,” Lucas says, “and when I started casting, which is a laborious job that goes on for ten hours a day, with a person coming into your office every two minutes, you try to be pleasant and sharp and to have your analytical eye attuned—but it gets to be very, very difficult day in and day out, week after week. So Brian asked if he could sit in on my sessions and I said, ‘Sure,’ because it’s great to have company, somebody to compare notes with and somebody to keep you alive, so you don’t become completely blotto toward the end of the day.”

“In the beginning we were very open,” Lucas says. “We had two male characters, so I wanted the farm boy to be shorter than Han Solo, so they didn’t conflict visually; I didn’t want two guys looking exactly alike. I also made a decision in the casting to lower the age considerably from what I’d had in mind, because I wanted to make a movie about kids for kids, though, in a way, it’s an adult kid’s movie.”

“We talked about Jodie Foster,” Crittenden says of the actress, who was about fifteen at the time. “We were down to that age. The princess was supposed to be about sixteen, Luke was about eighteen, and Han was in his early twenties. He was the old guy. But for purposes of shooting and having a full eight-hour day, people had to be over eighteen. It was incredible, the varied types of people that were brought in. We went so far as to send every school letters and we met people who had never acted before. We really wanted to cover everything.

“During the first week, by the third day, we’d seen nearly everybody—John Travolta, Nick Nolte, Tommy Lee Jones,” Crittenden adds. “Mark came in the second day.”

Twenty-four-year-old Mark Hamill was actually a little dubious about the test, according to Crittenden, because he already had a recurring role in The Texas Wheelers. “I think the TV series almost kept Mark from doing it,” she says. “When we saw him the first time, he wasn’t even sure whether he would be available. I really did have to persuade his agent [Nancy Hudson] that it would be beneficial at his age to do a feature film rather than to just keep his career stagnating in television.”

“My agent said that there was going to be a general meeting at Goldwyn,” Hamill says, “and that there was no script. The only thing she knew about the kid was that he’s from a farm. At that time, to show you how much I knew about the film, I started practicing a midwestern accent. So we were scheduled one every fifteen minutes—it was one of those. Thousands of people sitting on the floor; you wait two and a half hours, and then you go in and talk. And I talked to Brian De Palma. I think he introduced me, but George didn’t say anything all the way through it. I told them about my brothers and sisters, and how we moved around, living in Japan.”

His brief interview over, Hamill left knowing little more than before, and was immediately replaced by the next in line. While Lucas wasn’t making any decisions just yet about those he was seeing, De Palma hired John Travolta and Bill Katt, as well as Sissy Spacek and Amy Irving.

“By the second week, we were into the dregs already,” Crittenden says. “By the third week, we were just pulling people from colleges. But George wanted to see everybody. After a while Brian got tired and he dropped out.”

Consistent with his rethinking of each draft after finishing it, as the sessions drew to a close, Lucas flirted with the idea of casting only African-Americans in key parts. He talked with Lawrence Hilton Jacobs, who was playing Freddie “Boom Boom” Washington in the hit TV comedy Welcome Back, Kotter. Lucas also considered doing the whole film in Japanese with subtitles. While this last idea might seem to have grown from the drudgery of the casting sessions, it was actually related to his love of Kurosawa and a desire to re-create the feeling of disorientation he’d felt as a student watching films from different cultures. Lucas imagined what it would be like to watch a foreign film as if it had just washed up on the shore—all of its customs, history, language, and mannerisms strangely exotic, somewhat familiar, but not explained—an idea that would inform much of the style of the completed Star Wars as it had THX 1138.

“There was talk at one point about having the princess and Ben Kenobi be Japanese,” Crittenden recalls, “which led George into thinking Han Solo might be black.”

“This was actually when I was looking for Ben Kenobi,” Lucas says. “I was going to use Toshiro Mifune; we even made a preliminary inquiry. If I’d gotten Mifune, I would’ve also used a Japanese princess, and then I would probably have cast a black Han Solo. At the same time, I was investigating Alec Guinness.”

He entrusted Crittenden with the first step of that process, and she was able to put a copy of the script into the hands of the famed English actor in September. “I had a friend working on the film Murder by Death [1976] and I just said, ‘I would like to come over and see Alec Guinness,’ ” Crittenden says. “I went over and talked to him, and he said, ‘Let me see your script.’ George had cleverly attached to the script a whole set of sketches for the film, so I hand-delivered the script to Alec Guinness—who called me about two hours later and said, ‘I love this; I’m very interested in it.’ So I set up a lunch for George to meet him. It all happened without a middleman or an agent or a lawyer.”

In fact, Guinness almost turned down the picture when he realized what genre it was tapping. “I was in Hollywood making a movie, and on my second to last day a script arrived on my dressing room table,” he says. “I saw it was going to be directed by George Lucas, and George Lucas I knew about because of American Graffiti, which I admired very much. So I was immediately excited, but when I opened the script and saw it was science fiction, I said, ‘Oh lord.’ I’ve never done a science fiction [film]; I’ve seen one or two of them and enjoyed them, but I always thought they were sort of cardboard, from an actor’s point of view. But because of Lucas, I started reading it—and I found myself involved. There was an excitement in the script. I wanted to turn each page to know what happened next. I wanted to know how each little incident was concluded. It had a touch of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. It was a rather simple outline of a good man who had some magical powers. It was an adventure story about the passing of knowledge and the sword from one generation to the next.”

Lucas’s lunch with Guinness went well, with the actor being “impressed” by the “new breed of filmmaker.” But they were far from a contract.

Simultaneous with the three-week casting session in August and September, the ILM model shop had increased its output. Cantwell had by this time built a Star Destroyer, X-wing, Y-wing, Skyhopper (originally a good-guy fighter), a landspeeder, a small Death Star sphere, a TIE ship, and a sandcrawler. The last was a truncated pyramid with tiny “gravity grippers” that would search for things, according to McCune. “It had two little tanks that pulled it around and it looked more like a barge for picking kelp.” McCune and his team—at this point Bill and Jamie Shourt—realized that these concept models, while fanciful and ornate, were by the same token impossible to photograph. The models were consequently “heavied up” so they would work with mattes, and made large enough so they’d have room for essential motors, lights, and other equipment.

“The X-wing just kept getting fatter and fatter,” McCune says. “But the basic ideas for the pirate ship, Star Destroyer, X-wings, and Y-wings were all nailed down tight within the first thirty days. The TIE ship came right after that.”

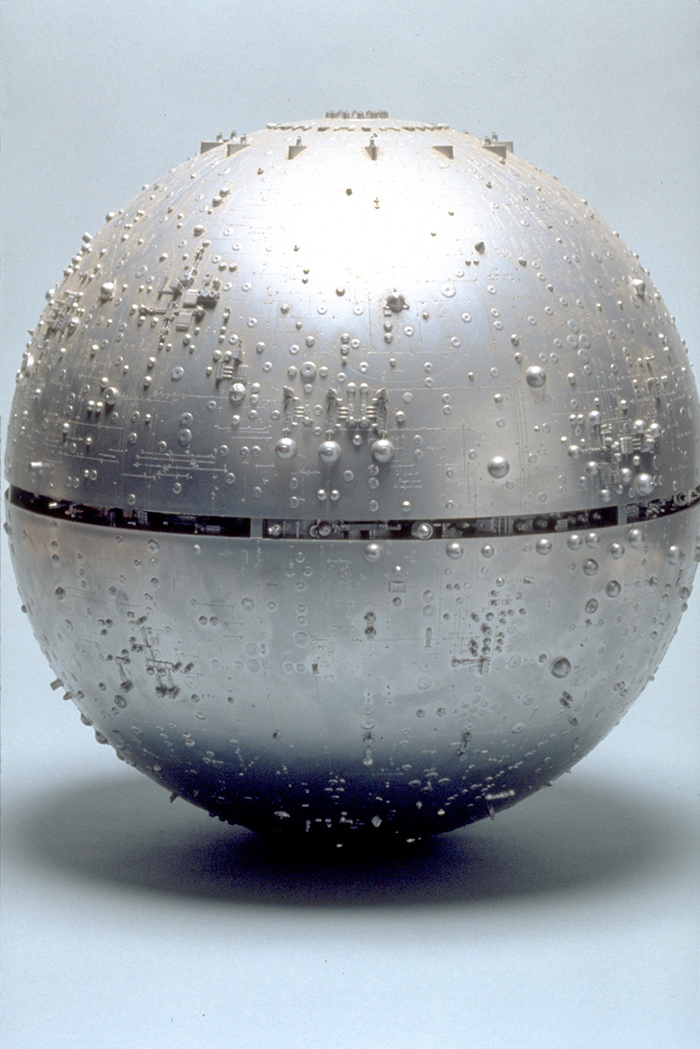

“I asked George whether the Death Star was always going to be near a planet,” Cantwell says. “He said it was, so I explored a very risky thing with a prototype model: I tried making it silver [far left, on top shelf], so you can set scenes where it would show in space.”

In John Dykstra’s office at ILM, Joe Johnston stands next to shelves exhibiting Cantwell’s concept models, from the top: Skyhopper, Death Star sphere, landspeeder, pirate ship, sandcrawler with tanks. Star Destroyer.

Lucas took a Polaroid of the last ship, penciled in its name, and gave it to McQuarrie for reference (“star d”).

Cantwell’s model of the Star Destroyer.

Cantwell’s model of the Death Star.

Models were a priority for two reasons. First, cockpits and ship interiors were going to be built in England based on the miniatures, but production couldn’t start until the models had been approved. Second—and crucially—they were planning on using front projection on the set for the escape from Alderaan battle with the TIE fighters, which meant that ILM had to have plates ready by early 1976. John Dykstra had used front projection on Silent Running, and one of the pieces of equipment he’d had Don Trumbull build was a front projection rig, with four-by-five plates and motors in it for rotating the image.

To help complete all the models in the allotted time, McCune hired David Beasley, whom Bob Shepherd had found in the “Unemployment Department.” To help with the redesign of the concept models and to create storyboards for the front projection sequences based on the third draft, Joe Johnston was hired to start the art department in August 1975. Earlier that summer Johnston had been working at Magic Camera on an aborted Paramount project, The War of the Worlds.

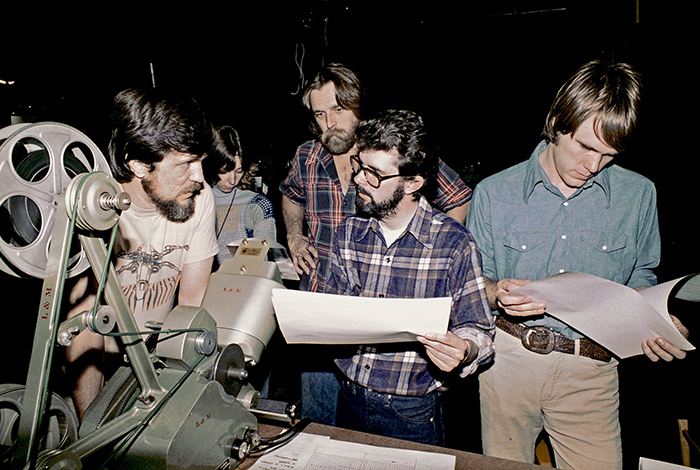

Richard Edlund, Rose Duignan, John Dykstra, Lucas, and Joe Johnston consult together.

“Bob Shepherd knew about me and called me up,” Johnston says. “I was going to the beach every day and really enjoying the summer, and he ruined it! [laughs] He said, ‘We’re doing another space movie and we want you to come up and see what you think.’ My first thought was, Oh no. I don’t want to work. I changed my mind, though, after I got there. It looked like a fun job. It looked like a good project.”

Johnston needed somebody to translate his concept drawings into orthographic schematics for the model shop as a basis for building, so Steve Gawley was hired (he soon segued into the model shop).

“John Dykstra and I sat down with Joe Johnston,” Lucas says. “John took the models and said that we had to change them, for his technical needs more than anything else. The wings had to be fatter or they wouldn’t show up in bluescreen, and we had to fatten the bodies up so we could fit the suspension bars in. Joe was the one who added all the aesthetics in terms of detailing.”

“George wanted all the rebel ships to look secondhand, old and beat up,” Johnston says. “He wanted them to look like they weren’t as well built or well designed as the Imperial ships. If he didn’t like a ship, he’d say, ‘Do more sketches.’ ”

“Joe was the only one who could draw from inside him,” Shepherd says. “He could really make images that you understood. So Joe would do a drawing, and it would get kicked around at that conceptual level. At some point it would be okayed, the drawing would be handed to Grant, and they’d say, ‘Build it.’ And he’d ask, ‘Well, how big is it?’ And they’d answer, ‘Well, it’s got to be this big for photographic reasons,’ or ‘We’re going to put a light in it.’ After the scale was established, the guys in the model shop looked at the thing and embellished it from their own head—they are artists in their own right—and that’s why they have to be able to think.”

From the beginning there was no question that new and valuable creative thinking was taking place on Van Nuys Boulevard. Complicated negotiations took place with the special effects hires. “We were involved in some new patent processes,” Andy Rigrod says. “We had to get licenses for them. There was [going to be] a huge staff, and every one of them had to be employed under agreement so they would promise to not give away the secrets that were involved in the processes.”

One of the most important processes was the creation of the motion-control camera John Dykstra had proposed. To understand why this camera was needed, one has to appreciate where special effects were at the time. If a director wanted a shot of several starships flying through space, his team would have to combine various pieces of film, all shot separately: a starfield, each spaceship, lasers, perhaps a planet, and so on. The different pieces of film would then be combined with an optical printer, which would enable the compositor to arrange the several pieces into one. This was a very expensive and tricky process, for a number of reasons. The miniature set would have to be left standing until the film came back—it was a “hot” set—because they’d have to use it again if any mistake had been made. Moreover, the process was so complicated that nearly all shots had to be static—the camera couldn’t move because it could never successfully and repeatedly film all the needed elements if it did.

The ILM model shop as it got up to speed: In the foreground are David Grell, Steve Gawley, and Joe Johnston. The door led to the optical department, while the wood shop was to the left of the model shop, and the motion-control stage to the right.

Model shop supervisor Grant McCune and model maker Dave Beasley in the model shop.

The Star Wars had an estimated 350 shots, each with as many as seven or eight elements—which represented a staggering amount of time and money doing it the contemporary way. “So we had to create systems that would allow us to shoot a shot, tear down the rig, then set up and shoot another shot—with the certainty that it would be okay one way or another,” Dykstra continues. “We needed to be able to record the information using the latest techniques to ensure that we were going to get something good to start out with—but also, if we didn’t get the shot the first day, a camera that would enable us to go back and do it again.”

Lucas’s short film of aerial action had also made it clear to everyone at ILM that the status quo of science fiction—static spaceships flying on rails—wasn’t going to be satisfactory. The X-wings and TIE fighters were going to have to dive, weave, and bank. “Before we developed the equipment for Star Wars, those moves could be made,” Dykstra says. “But it was a very complex problem to get them combined into one shot. You could make a zoom or a pan or a tilt during a shot, but to zoom, pan, and tilt in the same shot and maintain matte integrity was really difficult. So the moves were primarily linear in the films [of that time].” Complex moves had been created for commercials that had maybe one shot, but they’d never been attempted on such an ambitious scale, because it was too risky and expensive. “They weren’t viable in terms of achieving that effect over and over in a variety of situations.”

Not only would elements within the shot have to maneuver more freely but, to fit the director’s vision, the camera would also have to be able to move as if it were a handheld device in a cinema verité film—that way, people would feel like the space battle was real. Nearly every other film up until then had used what was referred to as a “locked-off shot,” in which the camera wouldn’t move during the special effects shot. To audiences, this was a telltale sign that they were about to see something fake. Nice, perhaps—but fake, because up until that moment in the film, the actors and objects, as well as the camera, would move about in a familiar way, and then suddenly everything would become still. Consciously or unconsciously, this would be a signal to the audience that something not occupying the same space as the actors was about to appear. But Lucas was adamant that he wanted his effects to occupy the same reality as his protagonists.

“It really means making the viewer feel as though it’s a real situation,” Dykstra says. “You can move the camera—you can watch a ship come from a distance and pan and follow him and watch him go away, covering a 180-degree field of view. In the old shots you saw a very narrow cone of vision. Everybody knows that you can line up one shot and have it look right, if you don’t move the camera. But if you start moving the camera, that is the subliminal cue to the person watching it, even if he knows nothing about film, that he’s watching real live-action photography. Because the moving camera puts him in a space. Instead of viewing a postcard, he’s seeing a three-dimensional reality.”

The motion-control camera would solve many of these special effects puzzles, because it could be programmed to repeat its actions exactly, an idea that had been around for several years. In fact, the camera would be the combination of three machines that already existed in different forms: a specialized camera, a specialized mechanical rig, and a specialized electronic-control device, all of which came to be called the “Dykstraflex.”

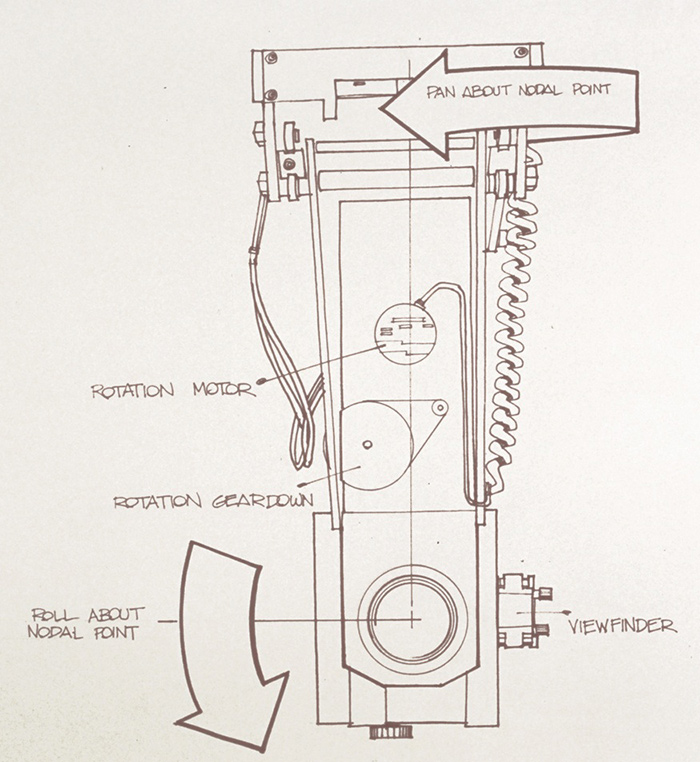

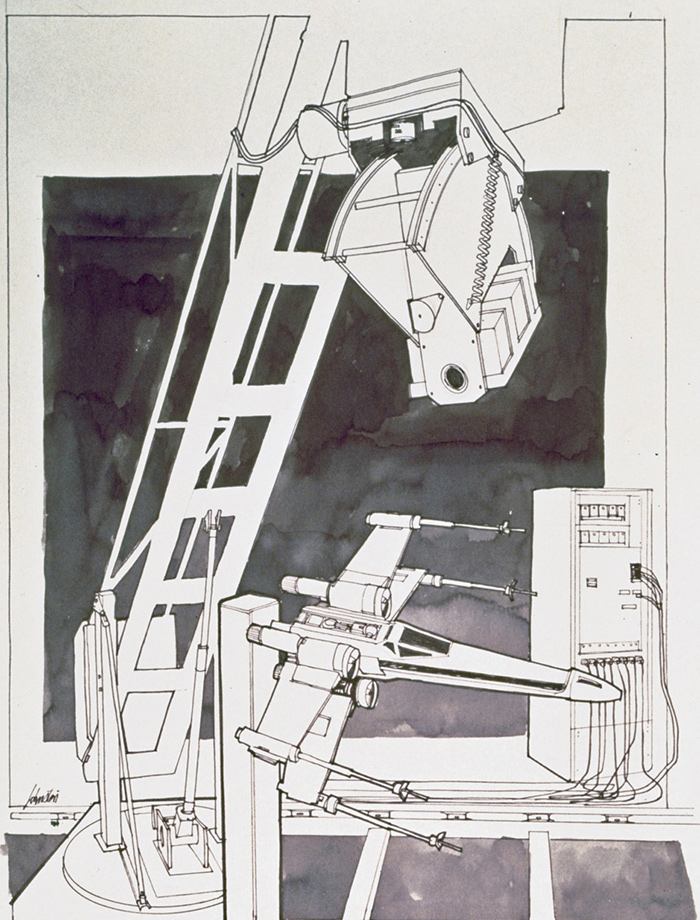

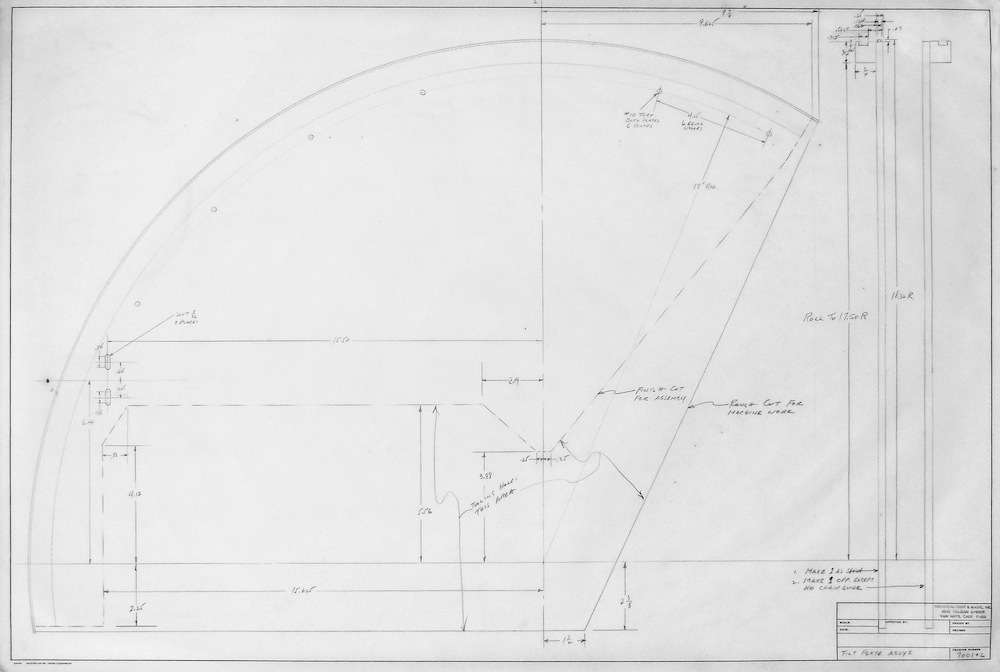

Technical drawings indicate how the motion-control camera would work and how it would photograph the models, which would be placed on blue pylons to hide the armatures holding them up—one of Dykstra’s innovations.

Joe Johnston, Steve Gawley, and others upstairs in the bare-bones ILM art department.

A blueprint for the motion-control camera, or “Dykstraflex,” is marked “tilt plate assys” (courtesy of Pete Vilmur).

“All three of the aspects of that camera system were developed at some point, partially, in the past,” Dykstra says. “Doug Trumbull deserves a lot of credit, because a lot of the people who worked on Star Wars were people that he nurtured. The name Dykstraflex was really a joke. The Dykstra-flex is not my camera; it’s not a new concept. It’s been around for years, from the days of the RKO General Pictures [in the 1930s]. The name of the camera is not indicative of its designer so much as it’s indicative of the joke that was going around. There was a Trumbullflex, and the same people that made the Dykstraflex had made the Trumbullflex.”

These same people were Dykstra, Don Trumbull, Richard Alexander, and Al Miller. “When we worked with Doug [at Future General], we had a camera that was similar but not quite as sophisticated,” Dykstra continues. “We had an electronic-control system that was far more sophisticated, but not nearly as useful. We had a mechanical drive system that was also more sophisticated but not nearly as versatile. Those elements were designed by somebody else; we went in and tried to figure out how to use them. Star Wars was our first opportunity to take those devices and make a device that incorporated all of their best aspects, plus any good aspects that we could come up with, and eliminate the problems.

“Al Miller and I sat on the floor in my house in Marina Del Rey, drank two bottles of wine, and came up with the outline for what the functions of the electronics were. At the same time, we figured out how the mechanics would have to work and a lot of the basic parameters for the camera. Then we went into the drawing stage and Bill Shourt and Richard Edlund and Dick Alexander and Don Trumbull—everybody had some input to that device.”

“The entire camera system was designed for Star Wars,” Edlund says. “Any trade-offs that we had to make were in relation to the film that George gave us—the 16mm edit of World War II clips that showed all of the dynamics, the cutting sequence, and the way the ships would move. We knew the kind of shots that he wanted; it was a tremendous help in preventing what could have been an arbitrary mishmash.

“John had been working with Doug Freeze [an engineer in Hollywood] and Don Trumbull a little bit before I got involved,” Edlund adds. “My main desire was to keep the camera as small as possible so that it could get as close as possible to whatever it was photographing, without depth of field becoming a problem—depth of field being the worst problem in miniatures, because if anything is at all soft, it ruins the shot. Everything was going to have to be absolutely crisp. One fuzzy shot in the whole movie and you’ve lost your credibility. So I redesigned all the lenses to some degree, adding extra f-stops to the lenses and things like that. Also, we made the camera head narrower than the camera, so that the models could fly above to the right, above to the left, and you could just miss them on the bottom; the fact that you could do that makes the shots much more exciting. It gives you the illusion that the camera is much smaller than it is—the smaller the camera, the greater the illusion.”

Most of the machine work was done in the warehouse on Van Nuys. They welded the tracks, which took about a month, bought war-surplus drives and stepping motors, and converted equipment. The hardware cost around $60,000.

“I’d say that the major construction took about six months [June to December 1975],” Dykstra says. “We had portions of it functioning before that, but there was a lot of lag time because of the unavailability of electronic parts. It’s a totally modular system, compatible with every other device in the shop. We used consistent plugs and connectors. We used the same power-drive systems. All of the track systems use pipe clamps, which means you can bolt pipes together to make whatever fantastic shape you need, and then disassemble them and re-form them into some other shape. They are very sturdy and give you supports for the ships or for the cameras or any oddball thing, which is real useful. It’s a workhorse device; it’s not a computer and that’s really important. It’s a calculator. It’s nowhere near as sophisticated as we could have made it with microcomputers.”

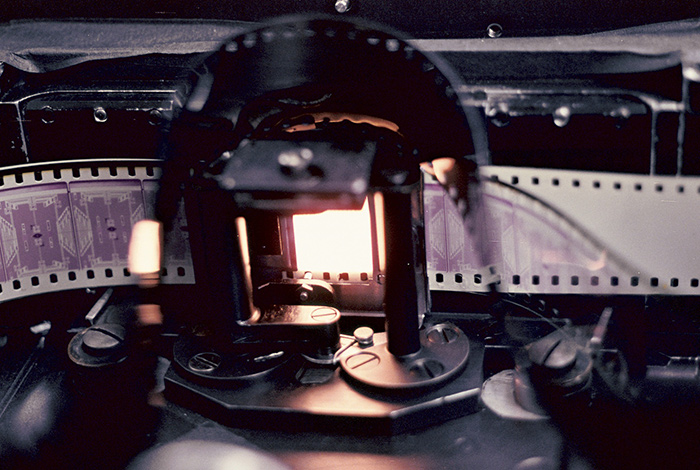

The VistaVision system had been developed in the 1950s by Paramount and Technicolor, but was short-lived. The idea behind it was to give the public an image whose size and quality absolutely dwarfed the black-and-white gizmo in the living room. “When television came out, the producers scrambled to come up with some way of enticing the people back into the theaters,” Edlund says. “As it turned out, VistaVision got shelved after a while. But a tremendous amount of money had been spent on cameras and equipment, which was just sitting around. A movement [inner-camera mechanism] that had perhaps cost $25,000 or $30,000 to build, we could get for a thousand bucks. So we amassed all of this stuff.”

Not only was the high-end equipment a bargain, VistaVision film was also the ideal format for special effects that were going to involve a considerable amount of duping. Instead of vertical 4-perforation film frames, VistaVision used horizontal 8-perforation frames, literally twice the real estate as standard 35mm film, which would still be used for all the regular live-action photography. “It gave us double the quality up front,” Edlund says.

“It’s like anything else,” Dykstra says. “The more area you use to record the information, the more information is recorded, the more detail. What that boils down to in motion picture terms is: You start with a large 70mm negative, and when you reduce it for 35mm projection, even though some elements have been duped, you end up with very nearly the original quality. You can go through one generation and still come out right about the same place. Plus, VistaVision allowed us to use every single film stock known to Kodak; everybody processes it, so it’s just easier to work with.”

While the motion-control camera was being built and VistaVision had been decided upon, the next step was to find the right optical printer, the job of Robbie Blalack. Having started doing theater at Pomona College, then migrating to nonlinear film and editing at Cal Arts in 1970, Blalack had founded his own two-person optical printing company in a basement after buying a 35mm machine from his school. “I brought my own optical printer to ILM,” Blalack says, “and we went out and found a second printer at Howard Anderson’s. We went to Anderson because nobody was manufacturing the movements, but he had the equipment and he had no use for it. He’s not into VistaVision.”

Anderson’s optical printer hadn’t been used since 1963, according to Blalack, having been built originally for The Ten Commandments in 1956. “That printer got totally reworked from the ground up, really,” he says. “After we bought it, we began a very long, difficult, and interesting period of updating VistaVision as a printing format. We used the existing movements and the existing bases, and built the take-ups; electronic motors were put on it, along with new optics, new lamphouses, new lenses—the whole works. That project lasted a good ten months, possibly even a year. We started with myself and Paul Roth, a friend of mine from Cal Arts, and we just kept adding people as we needed them and testing. There were no experts to help us, so we had the fun—or the nightmare—of doing that.”

From Anderson they also purchased a matte camera, whose parts were eventually recycled into a contact printer by Rich Peccarella. Another Blalack buy was a densitometer, to measure brightness, among other things. Many of the cameras put on the compositor and optical printer were old Bell & Howells from 1925, a testament to their durability. The equipment and upgrades for the optical department were essential in order to process the VistaVision film in an assembly-line fashion.

The last element in the VistaVision equation was a specially built editing table, or “motion-viewing system,” as Dykstra calls it. “We didn’t have the right editing device for VistaVision, so we had to make our own. We figured out how to do it so we could run six pieces of film in it—but it took us six to eight months to generate the technology.”

In the summer and fall of 1975—apart from building the printers, motion-control camera, models, and other complex equipment—ILM personnel also had to negotiate with the unions of Hollywood. “ILM was easy to set up,” Tom Pollock says. “We just rented the building. The tough part was the union problems.”

“The primary conflict was that the unions, when we first started on the project, were upset because we were bringing in people from the outside to do the special effects,” Dykstra says. “And their primary bone of contention [as they described it] was they had people who had been in the industry for years and years and years, who knew what they’re doing—and if we couldn’t find someone amongst their roster of people to satisfy our needs, then we wouldn’t find them anywhere. But I had to find people who were well versed in a variety of things. I interviewed their people and, quite frankly, didn’t find anybody that I wanted. So we continued to develop a shop without the union’s approval—in fact, negotiations were broken off by the union, not by us.”

“Fox was real scared,” Pollock says, “because they don’t like to cause any waves. They wanted us to use their sixty-five-year-old matte painters and miniature people who were over on the lot. But George was absolutely adamant that we wanted to set up our own shop with our own people. That was one of the control things that we’d been fighting about from the beginning.”

Part of Lucas’s independent streak came from necessity, but another part came from experience. “George learned a lot from Francis Ford Coppola,” says Matthew Robbins. “In his histrionic and flamboyant way, Francis would go out and hurl himself against the realities of filmmaking and film distribution, while George very quietly absorbed these lessons and built his own version of an alternate Hollywood. Not only was he very apart from the system, George was a rebel and was grateful to not be in Southern California. The whole culture of the studios and business managers, agents and lawyers, to him, was enormously distasteful and threatening. He felt that the Hollywood enterprise was corrupt. That it wasn’t really about creativity, it was about making money. I think American Zoetrope and a great deal of Lucasfilm was in reaction to Hollywood.”

“This is a business where hustlers come to town to make the quick buck,” says Charles Lippincott. “You lease the car, you lease that house and everything else possible, up to that mistress you may be living with; you make token payments to writers and pay everybody else with promises, and you sit out that year and see if you can make that one big killing. There’s a lotta guys that die here. It’s the valley of the quick kill.”

“George was shrewd. He understood Hollywood immediately,” Willard Huyck observes. “He was the same way in film school. After about two weeks, he said, ‘Oh, I see how it works.’ He figured out how to do his own thing, and it was the same thing in Hollywood. He understood it right away and said, ‘Yeah, I don’t like the way it works, I’m going to move to San Francisco and do my own thing from there.’ ”

When negotiations broke off between the unions and ILM, both parties were content to see how things developed.

In September 1975 Lucas and Kurtz headed back to London for one week. At this time production supervisor Robert Watts officially started, as did set decorator Roger Christian and art director Les Dilley. Watts immediately launched into the hiring of the English crew, preparing in conjunction with Peter Beale short lists from which Lucas made final choices.

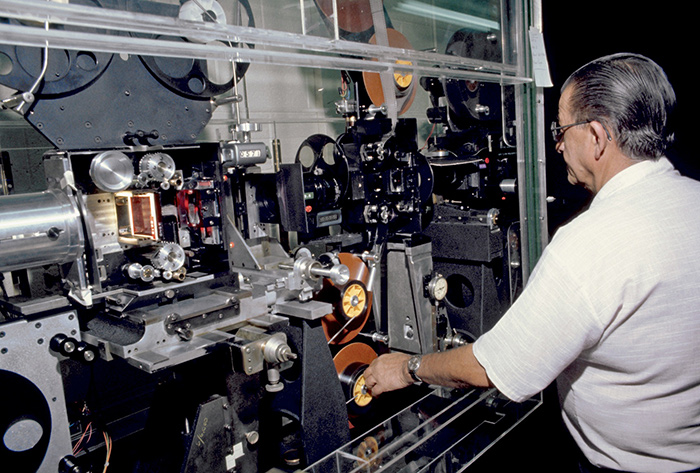

The Anderson optical printer (with Don Trumbull) was one part of a complex special effects system that also required particular celluloid considerations. “We had steadiness problems based on the perforations, so Kodak would send people out from Rochester [New York] to help us work this out,” Richard Edlund says. “They took pictures of my setup; they took us very seriously and were very helpful. I would order special films [laughs] that hadn’t been made since the Second World War because they had certain qualities that we needed for testing or whatever. So they would make up special batches of film for us and put it on ESTAR Base [ESTAR Base is coated on thin 0.0048-inch (120-micrometer) ESTAR (polyethylene tere-phthalate) base], which is like polyester but much harder and thinner.”

Operator James Van Trees, Jr., works with the Praxis VistaVision printer.

An aerial view of EMI (Elstree) Studios in England, which became one of two studios for the Star Wars production.

“I’d rather have a nasty person who’s good at his job than a nice person who’s lousy,” notes Watts.

Of course that crew would have to have a studio to work in. While Pinewood had been the front-runner, Barry had told Kurtz back in August that, given the size of the production, just one studio would not be enough. “When I got to the very first meeting, we sat down and I asked, ‘Where should we go: to EMI and Pinewood, or Pinewood and Bray Studios, or Bray and Shepperton, or Shepperton and EMI? It won’t fit into one studio, will it?’ ” Barry says. “Because, as I’d read through the script, I’d done a sketch plan of each set, and the size of that set. I then explained that if you are lucky enough to get up a big set, you shoot it in two days—and it takes another month to get up another set on that stage—which means you can only use a big stage twice in your schedule. So there was a shuffling of feet and looking around …”

Subsequent to Barry’s revealing ratio of sets needed versus stages available, Kurtz did more research. By fall the combination of EMI and Shepperton Studios had won out. Just a few miles north of London, EMI (also known as Elstree) was selected as the main studio because they had no scheduling conflicts; could offer Stages 1 through 9, except Stage 5, which they’d leased to Paul McCartney; and had the best facilities. The two largest sets would be built on Shepperton’s enormous H Stage. EMI would also allow them to maintain their own departments. “You can come in here and work completely independently of them,” Watts says. “You just rent the studio—four walls, if you like, which is a good system.”

“We took over completely: lock, stock, and barrel,” Barry adds. “We have a freelance crew here, and freelance people tend to be more on their toes.”

Because Lucas had elected to film in England, it was only natural that local actors be cast in many of the supporting roles. “My agent rang up and she said there was this man called George Lucas making a ‘space film,’ do you want to go and see him?” says Anthony Daniels. “She said they were very interested because I’m good at mime. She talked a lot about the film and said the only trouble is, the part is a robot. So I said, ‘Oh come on, I’m a serious actor. We’ve got to get on with my career, don’t we?’ But I went to Fox and met George, and I must say that I did immediately like him. We greeted each other and then there was silence. Fortunately for both of us, the production paintings were on the wall facing George. So I turned to the pictures and asked him about them, and he opened up and became quite dynamic. His excitement spilled over, and it was about an hour later when my meeting ended. A couple of days later, I picked up a script and read it for the first time—and it took me a long time to read, so I thought I’d better read it again. After reading it three times, I wrote out the story in sections and when I got to understand vaguely what it was about, I became very excited about the character See-Threepio. I realized he was not an ordinary robot and began to forget all of my original ideas about playing a robot.”

That robot’s costume dollars, however, were part of an overall special effects budget that John Stears had long since completed—but which was not forthcoming from Twentieth Century-Fox. “We had John Stears and about two or three special effects guys, but we needed to actually start construction on the robots,” Lucas says, “which meant a commitment of money. It meant hiring many more people and actually starting to build those robots. But Fox wouldn’t commit—and we needed them to commit in September.”

Elliot Scott had long since completed a set cost budget (moving on afterward to a prior commitment)—but as there was no green light from the studio, there was no money for that department, either. “I had meetings with Fox,” Kurtz says, “and they came up with certain budget estimates on set construction, wardrobe, and special effects—that’s one of the things that made the studio nervous: the special effects area. Between the first and second and third drafts, the story changed considerably. We redid the budget over and over again. One of the budgets I did was $13.5 million direct, without overhead.”

Lucas and Kurtz returned to the States for more budget talks, while Robert Watts and John Barry departed to location-scout in North Africa. Back at the source of Fox’s worries, ILM was indeed running up quite a bill—$241,026 by August 8—with operating costs of about $25,000 per week. “They had built a lot of equipment and were spending money right and left,” Kurtz says, “and we hadn’t seen anything yet. But we weren’t supposed to see anything until Christmastime at the earliest.”

“Fox didn’t know whether we were on schedule or ahead of schedule or behind schedule—or even if there was a schedule,” Shepherd says. “It was a new type of picture.”

Production designer John Barry (holding rolled-up blueprints), art director Norman Reynolds, Kurtz, and Lucas inspect the second studio, Shepperton Studios, standing in its enormous H Stage.