On October 1, 1975, Bunny Alsup traveled to England to set up house for Kurtz and his family, who followed on October 6, 1975. Lucas settled overseas shortly thereafter, as preproduction hit full speed in preparation for a March start to principal photography—at least, that’s what was supposed to have happened. Everything changed when, in mid-October, Fox’s worries mushroomed into full-blown panic.

Like nearly all the major studios during the 1970s, Twentieth Century-Fox was having good days and bad days, and many of its corporate decisions were based on transitory moods generated from the latest box-office or production reports. The fate of The Star Wars wasn’t being helped by Fox’s most recent big-budget experience: Lucky Lady, which was about to be released with much justifiable hand-wringing. “Lucky Lady was a fiasco,” Kurtz says. “And it had been in the same position that we were: Lucky Lady had started as an independent picture. Stanley Donen was controlling everything himself. They were leaving him alone—but halfway through production he got into serious trouble. The studio had to keep flying down there and they eventually took over the entire production. That experience was very fresh in their minds when we were making our picture.”

In other words, Fox thought they could see the handwriting on the wall—and pulled the plug.

As of the middle of October, the studio imposed a “moratorium” on The Star Wars production. People were paid their salaries, but Fox refused to finance any further development until the board of directors meeting scheduled for December 13. At that time, the fate of the film would be decided.

“There was a bit of hysteria around here at that point,” Alan Ladd says, “because we’d just come off Lucky Lady, and the company was getting very bad press about it being the most expensive picture Fox had made since 1969. And Lucky Lady’s cost had at least been covered in guarantees, while the budget for Star Wars kept escalating and escalating [with no such assurances]. We kept setting certain budgets and it kept increasing and increasing and increasing. There was concern because the research and development kept going on and on, and nothing was being seen. A couple of people came in and said, ‘Look, it’s never going to stop unless you just say, That’s it.’ ”

Even with the paintings and concept models as visual aids, Fox was not clear about the goals of the film and the corresponding crucial role special effects would play. ILM’s investments in developmental technology “confused” them, according to Ladd, while John Stears’s feasibility study on the other side of the Atlantic didn’t please them.

“I just don’t think they were as aware as they should have been about how a film like this gets made and the fact that things have to be done way ahead of time,” Lucas says. “It takes six months to design a robot and build it. They just figured you could do it in six weeks, because they’re used to making television movies where you come in and three weeks later, everything is ready to go. This isn’t that kind of a movie, and the more time and money that’s spent up front, the less time and money you have to spend actually making the movie. You save money.”

“Fox’s position was no contracts, no approved budgets, no money,” Pollock says. “And they were all over in England preparing to shoot. The special effects unit had started. George was already $400,000 of his own money into the movie. Not yet reimbursed. He had advanced that much money, the bulk of which went to get ILM started, because Fox just wouldn’t pay for it until they had a budget approved by their board.”

Lucas’s accounting records reveal that he began making personal loans to the Star Wars Corporation in October 1973, for salaries and other expenses—and given Fox’s reticence he would have to continue subsidizing the film through the fiscal year 1975–76 for a grand total of $473,368. Though the trajectory of the film’s budget estimates is difficult to plot precisely, the basic upswing was from $3 million at the time of the treatment to about $6 million to $8.2 million; yet, strangely and somewhat irrationally—given that at one point the budget had ballooned to $15 million—Fox’s panic ensued after the budget had been brought back down. “My final realistic budget was $8.2 million direct [without overhead],” Kurtz says. “But they insisted we cut back. They stopped work on everything, and insisted that we cut the budget back to $7.5 million. So we went through the exercise of doing it. Laddie kept asking me if this was going to be realistic, and I said, ‘I doubt it. If you want to present it to the board that way, it’s up to you.’ ”

“George made the comment that it’s really a $15 million movie being made for half its budget,” recalls Lippincott.

“Ladd just couldn’t go to the board and say it was going to cost more than a certain amount,” Lucas says. But at the time, the director was unaware of Ladd’s relationship with the board and the intrigues at Fox, and could only stand by looking on in anger at what was happening to a film he’d worked on intensely for more than two years. Not surprisingly, on October 22, 1975, Variety noted the presence of Lucas and Kurtz “in town working on budgeting of their multi-million dollar sci-fi epic, ‘Adventure of Star Killer’ [sic].”

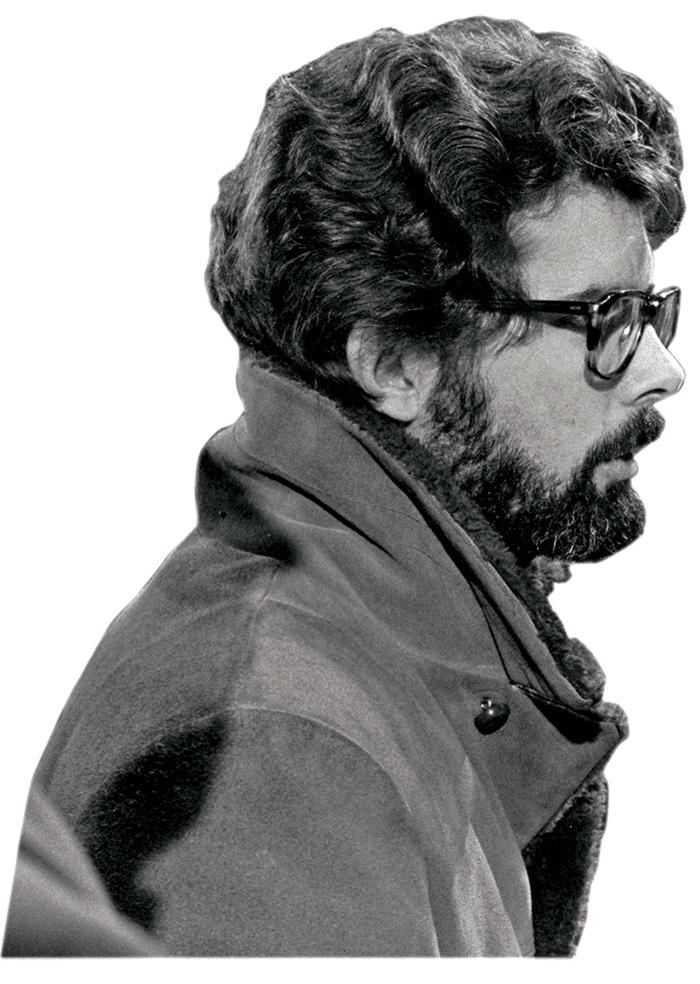

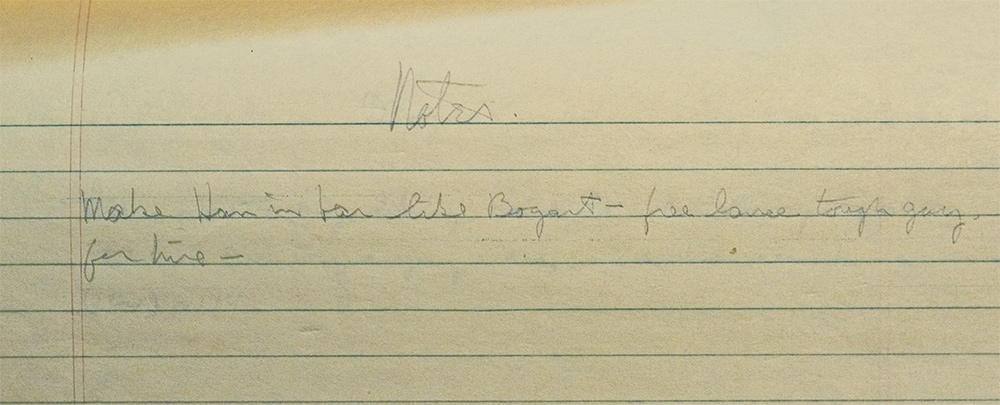

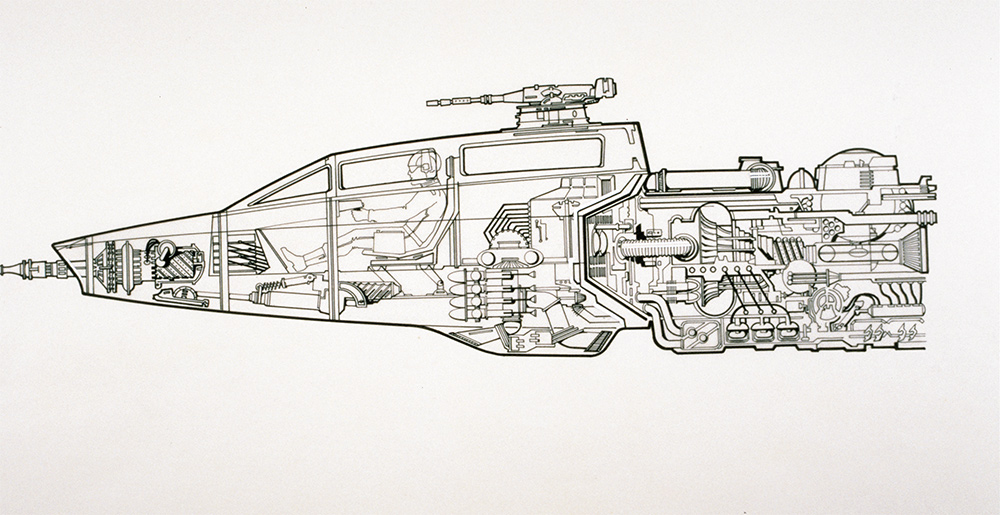

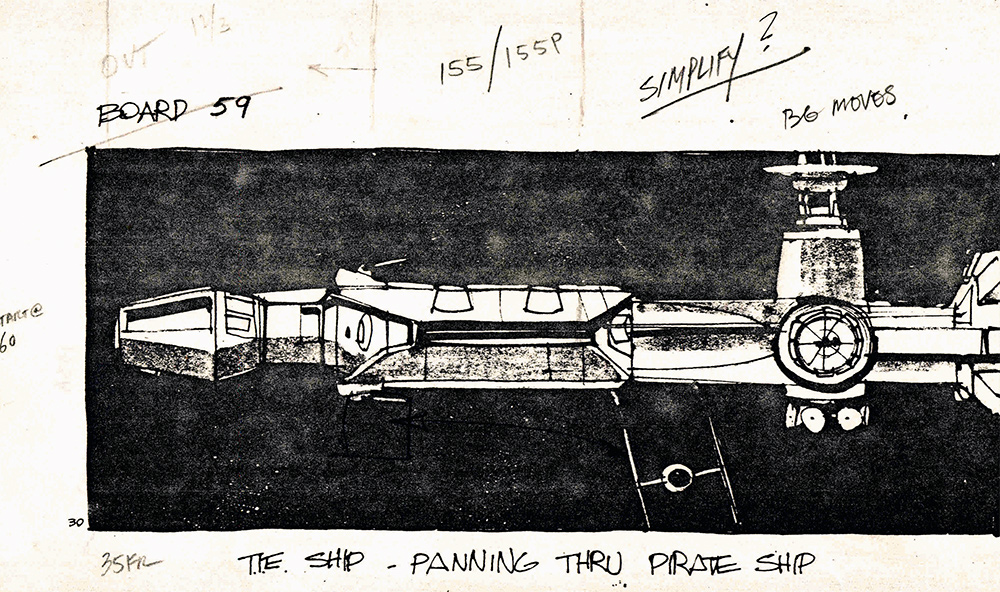

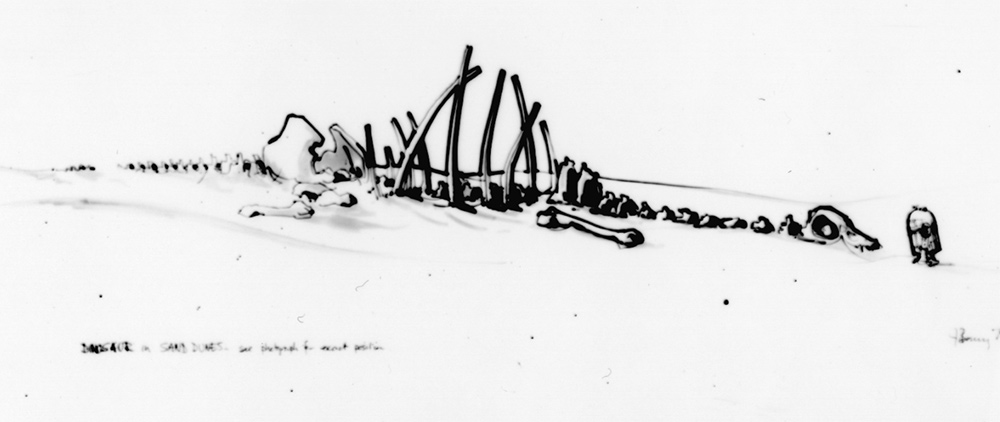

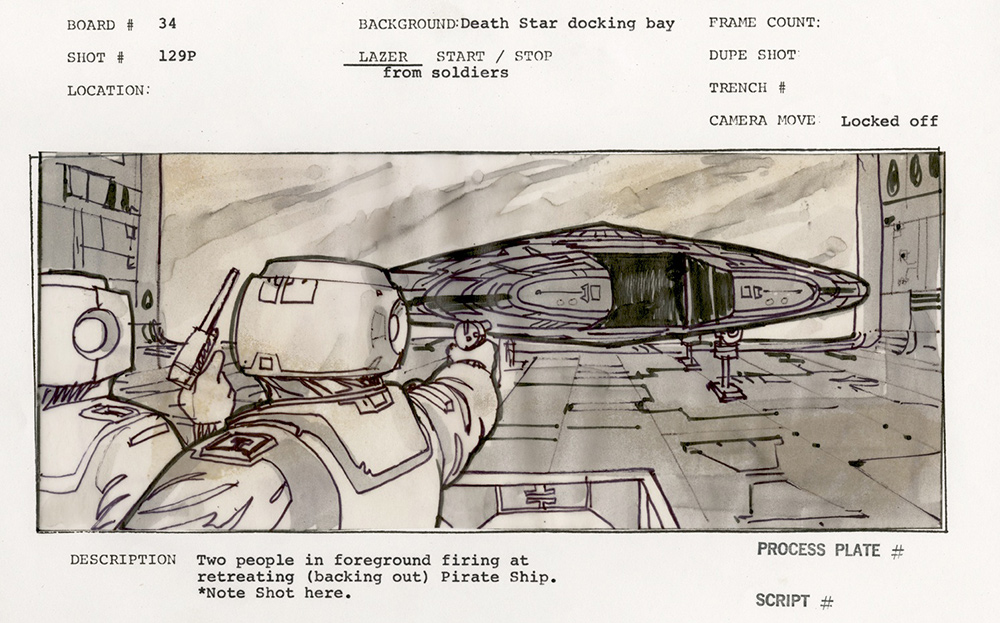

Lucas’s notes indicate his earlier thinking on the development of the Han Solo character, as well as his thoughts on the developing fourth draft—in particular the attack on the Death Star (first image).

As October crept into November, stress levels rose and the clock kept ticking. A March 28, 1976, start date had been agreed upon, which was key because of the location shooting in the desert. There was a certainty that if they went beyond that date, the actors in the robot suits would not be able to survive in the heat. So after feverishly reworking the numbers and making changes that would have a long-lasting impact on the film, Lucas and company turned in a revised budget for the amount specified, thinking it was done and approved—when Fox insisted that the $7.5 million include overhead, which meant that another $600,000 had to be shed to lower the budget to $6.9 million direct.

At this nadir, Lucas—because he still had no contract, was earning a pre-Graffiti salary as writer-director, and had invested a large percentage of his savings—saw little hope for success. “I thought Star Wars was going to make anywhere from $16 to $25 million,” he says, “which would have been successful. But when the price got way up there, I became very pessimistic. I could rely on a low-end box office of $16 million, but if it cost $8.2 million, after you put the advertising and all the costs on it, we’d barely break even. And when Fox took away six weeks of our preproduction time, I knew it was going to cost us three or four weeks of shooting time; as a result, those three or four weeks were probably going to cost ten times as much as the six weeks in preproduction, because there are so many more people involved.”

“George always described it to me as a kids’ picture, a little Disney film, that he didn’t think anyone would want to see, but he wanted to see it,” Steven Spielberg says. “He would get excited about it, telling me the story and showing me Ralph McQuarrie’s concept paintings, which were phenomenal, but in the next breath he would be putting down its commercial chances.”

“In the end,” Lucas sums up, “I really didn’t think we were going to make any money at all on Star Wars.”

Besides creating a dim view of the long term, the studio-sanctioned delay was wreaking havoc from Los Angeles to London.

“We cut back 10 percent of John Barry’s art department budget, across the board, without even consulting him,” Kurtz says.

In a series of what must have been painful conversations back in London, Lucas and Barry went through the script, which Lucas was busy transforming into a fourth draft, and tried to find areas where they could decrease costs. “If we had a scene that involved a lot of extras that was tied in to another scene,” Lucas says, “we would either eliminate the scene with all the extras or plan on shooting them at one time. Part of it had to do with camera angles: If I wanted to shoot certain angles, we’d have to build more sets, so I would eliminate those angles. I cut out scenes. The compromises had started, and it was difficult—because we had already cut it down to the bone and then we were faced with the fact that we had to cut it even further.”

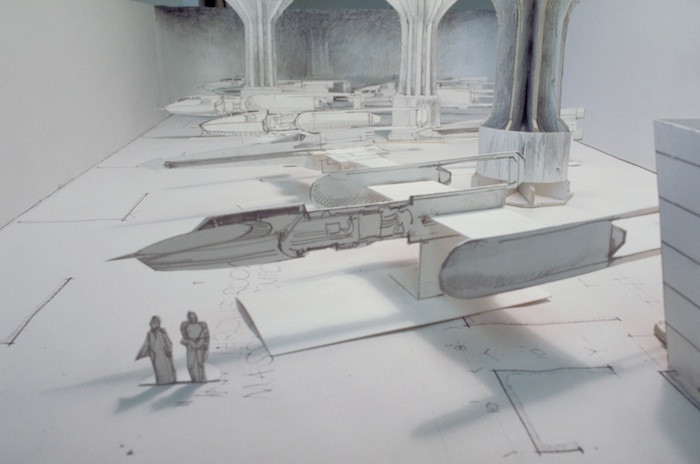

Lucas and John Barry look over set design maquettes, with Lucas checking out the available camera angles.

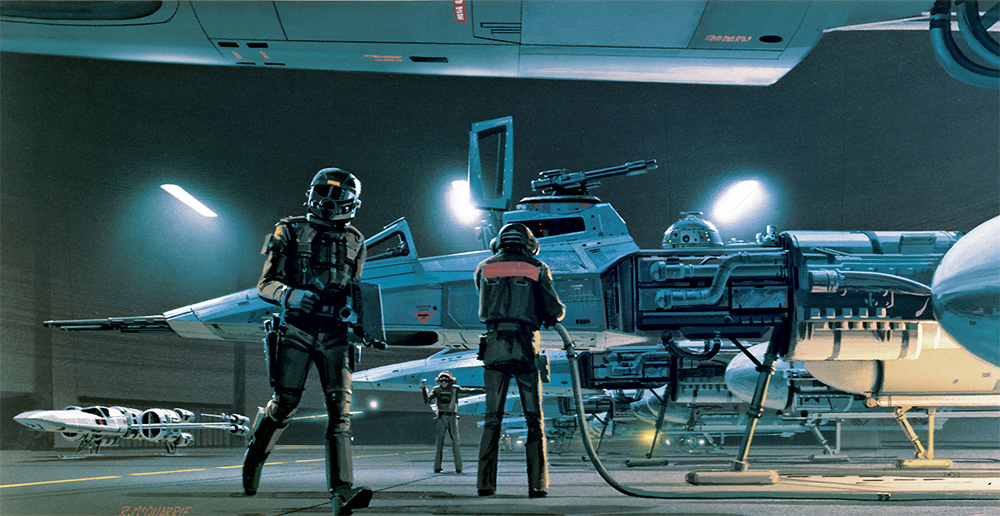

Redesigned Y-wing.

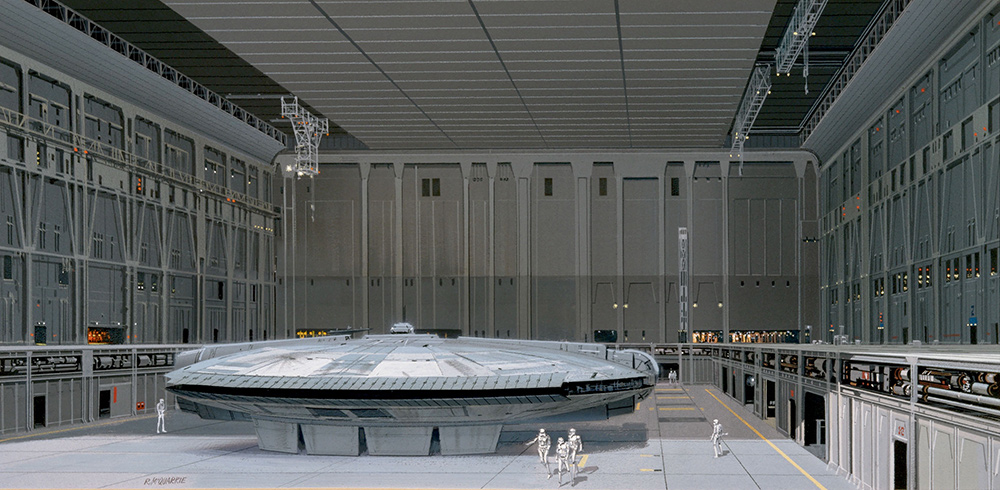

Budget cuts led to McQuarrie’s circa January 1976 painting (with redesigned Y-wing), as the rebel starfighters were moved inside on Yavin to save money. “I saw a navy pilot that was running across a flight deck with a clipboard in a World War II photograph,” McQuarrie says. “I took him, and repeated the same gesture, but changed the uniform and put a helmet on him. The ships of course were Joe Johnston’s design. The fighters were lined up in these long rows and were towed down to the launching platform, which had doors that opened, so the fighters would come shooting out. George liked that basic idea; at least he thought it was fine to have the fighters inside, because it solved some problems of shooting them, too, because the overhead would just be black [instead of jungle].”

A maquette built by John Barry’s UK art department of the rebel hangar.

Cost-cutting measures went from the small—the Mos Eisley hangar was originally supposed to have a sliding concrete slab overhead—to the big: Alderaan was cut out of the picture, and all of its scenes were transferred to the Death Star. The rebel base, originally located outside in the jungle, was moved to a less technically challenging and cheaper set inside a temple; Ben Kenobi’s house was also scaled down from a multilevel structure to a one-story home with windows to make it easier to light. “Ben’s house was originally a very bizarre three-story cave, all carved out of rock, much bigger than it is now. Budget cuts forced us to change that,” Lucas says.

The delays affected personnel as well. Director of photography Geoffrey Unsworth had to back out, so Lucas replaced him with Gilbert Taylor. “A Hard Day’s Night [1964] and Dr. Strangelove [1964] were two of my favorite movies. I loved their style, and then I had seen Macbeth [1971] and had seen Gil worked well with color, too. But I was really more intrigued with the documentary style of A Hard Day’s Night and Strangelove. I wanted the film to look like those; that was really why I hired him,” says Lucas.

“When George asked me to do Star Wars I was delighted,” says Taylor, who had been impressed by American Graffiti. “It fitted in with our finishing time, which meant a large number of the crew on The Omen [1976] could also join the team. Many of my crew had been associated with me for over twelve years and worked efficiently and fast.”

Decreasing dollars also meant bringing in a local editor, John Jympson, rather than Northern California resident Richard Chew. Lucas had been talking with Chew, a San Anselmo acquaintance who had edited The Conversation (1974) and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). But Chew was expensive and, at that time, tired from his latest editing gig, whereas Jympson meant less money, no travel expenses, and no work permit problems. “I had never really worked with an editor before,” Lucas says. “I had cut my own movies, so I didn’t really have a relationship with a regular editor and it was very difficult to come up with somebody. We tried to get one editor first and we didn’t get him, John Victor-Smith. But Jympson had cut A Hard Day’s Night, so I talked to him, I liked him, and he seemed like he was going to work out.”

Some of the changes engendered by budget cuts actually provoked sighs of relief at Industrial Light & Magic. “We were going to have to make Alderaan, which I wasn’t looking forward to,” Dykstra says. “All of those clouds.” Which also allowed them to scrap the idea of renting a Learjet to film billowing formations. News of fewer scenes on the jungle planet was also welcomed.

The much larger and extremely long-term effect, however, was to make it pretty much impossible for the special effects crew to deliver quality front projection plates in time for the live-action shoot.

“I guarantee you a week of no nourishment from the umbilical cord to a fetus is going to do a lot more than just make him a week younger when he comes out,” Dykstra says, angrily. “We ended up in a situation that we could not compensate for, and nobody from the studio came out here and said, ‘Oh, I understand the problem.’ They just said, ‘Well, there’s no money, but we want the stuff on the same day.’ That’s bullshit. It isn’t ever going to happen—but it doesn’t do any good to make excuses, because what’s important is getting it done. But that really hurt us badly—and it was really a morale loser, too, because it was obvious that we weren’t going to make it.”

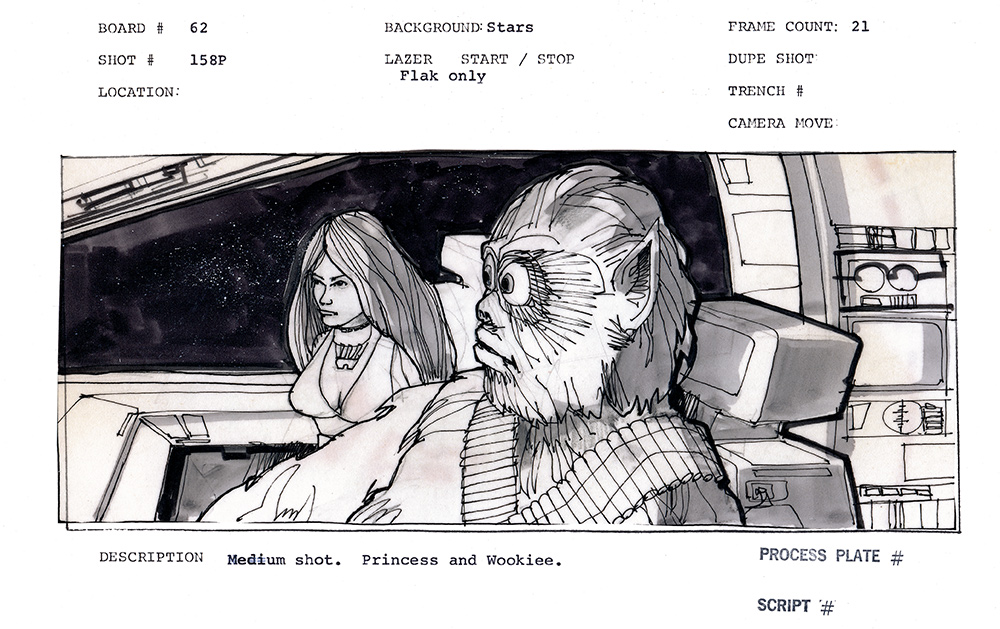

“What we were faced with then,” Robbie Blalack says, “was a delivery schedule in England. I believe, starting in April of ’76, we were to deliver a series of process plates, and the first sequence that was to be photographed was the gunport sequence. Actually, the first part of it was to be the pirate ship cockpit, distinctly different from the gunport.”

In an effort to manage the worsening situation, Joe Johnston was hard at work on the special effects storyboards for the front projection sequences, taking over from Alex Tavoularis, whose work had finished in mid-June. Johnston’s storyboards had been submitted to Lucas and revised on October 10 and 22, 1975. “The first job that ILM had was to take that 16mm film, with the script that described everything, and draw a storyboard for each frame of film,” Lucas recalls. “Because you can’t do it intellectually, though even storyboarding it is difficult.”

“George, John, and I would sit down and we’d have three- or four-hour meetings,” Johnston says. “George would talk, I would draw, John would sometimes suggest how the shot could be done more easily, and that’s really how they were done. It was just a matter of George saying, ‘This is what I want to see, or I want to see two ships drop into frame and come right at us.’ I would sketch it out real quickly, and they’d look at it and say, ‘Yeah, that’ll work.’ I’d put a number on it and put a description underneath, and we’d do another one. It was a really slow process.”

Not only was it tedious, it was a process that somewhat troubled the film’s director at the time. “I’ve got a tremendous storyboard for the action sequences,” Lucas says. “I haven’t really done that much storyboarding in the past. I like to do it, but when you bring in a storyboard artist, they bring a lot to it. You tell him what to do, but they end up bringing in their graphic designs. In a lot of movies, I’ve seen scenes that looked like storyboarded scenes—you can see the way it was done—and I’ve always been much more loose about how things come together while shooting it. That’s something I’ve always enjoyed. I like to be able to think about things on the set, because things happen slightly more randomly that way. It’s more interesting.”

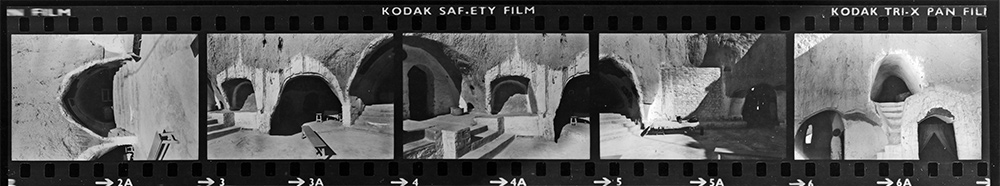

In November 1975, leaving the robot designs and the few sets that had already been started in limbo, Robert Watts and John Barry left for their second North African scouting trip, to Morocco and Tunisia, which Barry knew well thanks to his location shoot there on The Little Prince (1974) as well as a more recent solo trip for The Star Wars. The candidates had been narrowed down to those two countries from a list that had originally included Iran, Libya, Turkey, Spain, and Algeria; Lucas had wanted to film in the latter country on the same location Michelangelo Antonioni had shot the scene in which the Land Rover breaks down in The Passenger (released in the United States on April 9, 1975). However, Algeria and Libya were too politically volatile for Fox, while Iran was too far away for efficient transportation. Moreover, Lucas had been intrigued by the photos Barry had taken on his previous recce. “I did quite a big trip around Tunisia looking for interesting things,” Barry says. “Djerba had this white architecture, and George liked the look of that from the photographs; he also liked Matmata, where people live in these holes in the ground.”

Barry traveled with a list of logistical and artistic prerequisites, the gist of which was that the locales had to meet the environmental and stylistic needs of the script while not overwhelming any scene, which might take audiences out of the story.

“John and I went to Morocco to see how it compared to Tunisia,” Watts says. “We went down to the south where we found sand dunes and a bit of canyon. But the architecture was very Arab; everything looked like Beau Geste. After about a week, we called George from Casablanca and said, ‘It isn’t as good as Tunisia.’ John and I then went from Casablanca to Djerba, where we met up with George and Gary. And the minute George saw the island of Djerba, he made the decision to film there, which really keyed from the architecture, because it is strange and it was right. Having got the architectural key to it, we went to the south, where the sand dunes were sufficient, and then we visited the salt flat and the strange hole in the ground.”

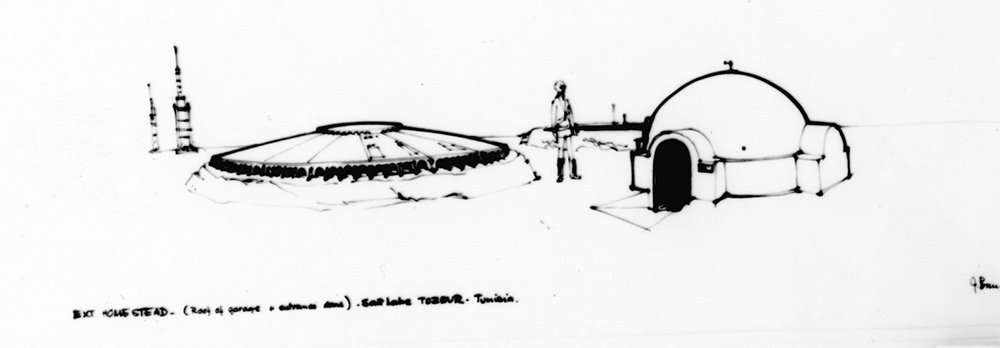

As they were led from location to location by a Tunisian guide, Lucas began to form in his mind the various locales into physical spaces that made sense within the story. “I loved the architecture in Djerba and I loved the salt flat and that hole—I was real excited about that,” he says. “But I had to fit them together, so I came up with the idea of having the homestead out on the flat, in one location, with the hole in the ground in Matmata. It would be very bizarre and I thought that would be a great idea—but everybody was very upset about that. It meant we had to shoot two locations instead of one, which meant another day shooting and more money. But I thought it’d work out very well—it was one of the really rewarding finds.”

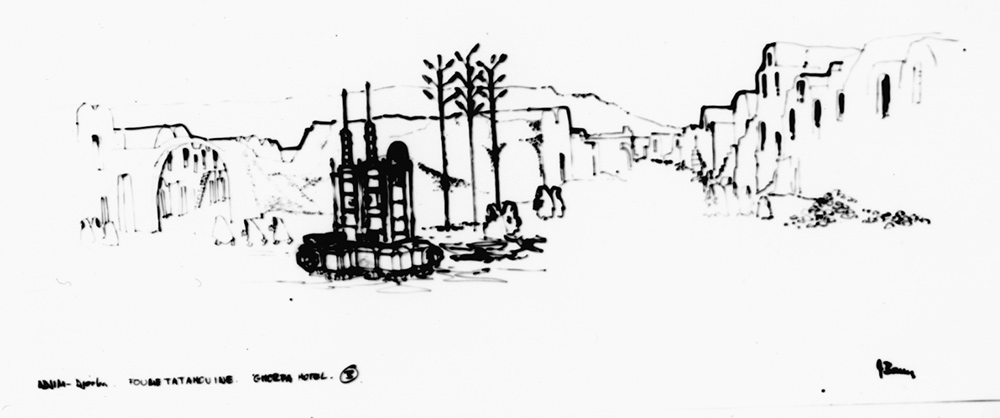

Another location they visited was a “fabulous series of old grain stores that we were going to use as a street in Mos Eisley,” Barry says. “We didn’t get to use it, but you’ll notice George used its name in the script, Tatooine—one of the planets is called that.” Lucas integrated that name into the work-in-progress fourth draft; the Mos Eisley scene never made it into the draft, but would’ve featured the Jawas.

“We found these great things in Tunisia, little grain houses that were four stories high but with little tiny doors, little tiny windows, it was a hobbit village,” Lucas says. “We had a whole sequence with these little hobbit-world slum dwellers but we had to cut it out.”

In addition to its artistic advantages, Tunisia won out over Morocco because it was logistically superior. “Its locations change very quickly in a very short distance,” Barry says. “The sand dunes, the big ravine, and the salt flat location—they are all within thirty minutes of one another, which is amazing. And the sand dunes were accessible by truck. It’s dreadful, isn’t it, to think that that’s what moviemaking revolves around? Instead of ideas, it revolves around, ‘Can you get hotel rooms or can you get there on a plane?’ ”

In fact, Fox’s delays were forcing them to overlap with something truly horrifying: tourist season. “Packaged tours to us are dreadful,” Watts sighs. “They book so far in advance, taking all the rooms, and they get a better rate—because film productions never have the ability to book a year in advance, ever. I’ve suffered this in many countries in the world recently, because this is a recent innovation. Cheap packaged tours.”

On their way back to California in mid-November 1975, Lucas and Kurtz stopped in New York City for an East Coast casting session. Lucas interviewed Jodie Foster for the part of Leia and Christopher Walken for Han, the latter, according to Kurtz, becoming a favorite in the eyes of Fred Roos. By the end of November they had returned to Los Angeles. While Kurtz departed once again for England after the first week of December, Lucas continued work on the script, supervised efforts at ILM, and gave new assignments to Ralph McQuarrie, who had gone freelance during the months of September and October (working on The Adventures of the Wilderness Family, 1975; and The Winds of Autumn, 1976).

McQuarrie would occasionally work at the new ILM premises, in order to study and then incorporate Joe Johnston’s latest vehicle modifications into his illustrations. An early ILM hire, who had been a student of Jamie Shourt when Shourt was a university professor in Colorado, Paul Huston remembers a late-November visit: “There were maybe ten people in the little warehouse. Joe Johnston and I were upstairs in the art department, where we had these wooden tables on sawhorses on the plywood floor, and we were just drawing X-wings all day with our tracing paper and Rapidographs. But when Ralph McQuarrie would come in, Bob Shepherd would let the word get out that Ralph was there. Everybody would go to the front office and there’d be one of Ralph’s illustrations on a piece of illustration board with tissue paper over it. One time Ralph folded the tissue paper back to reveal this painting of a TIE fighter over the Death Star with an X-wing—just this incredibly detailed, beautiful painting. I’d never seen such a high quality of skill. I was just knocked out by that vision.

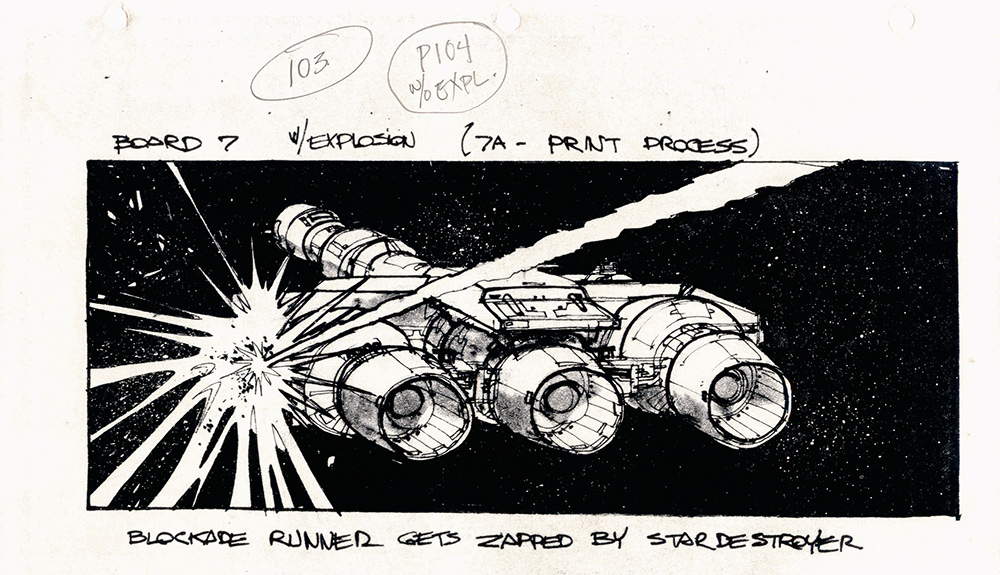

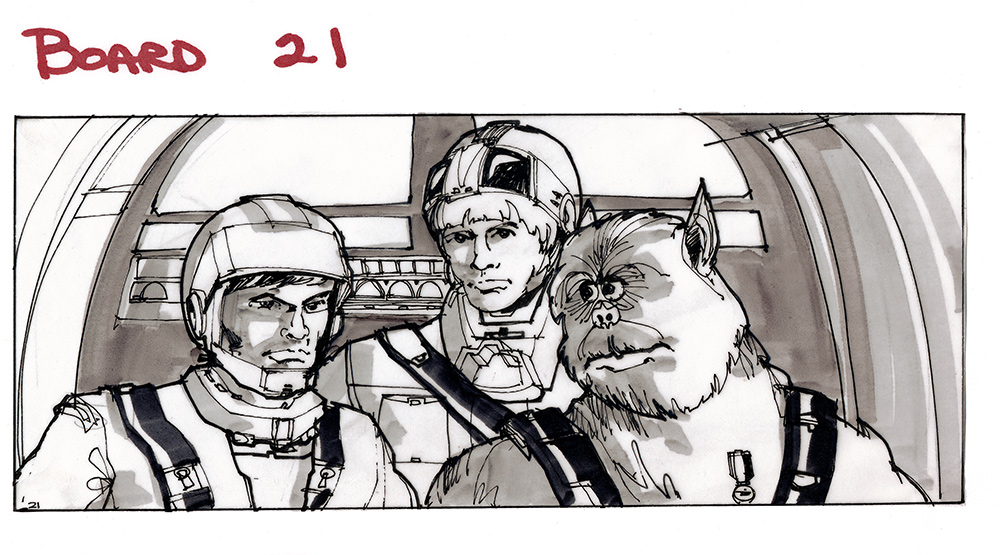

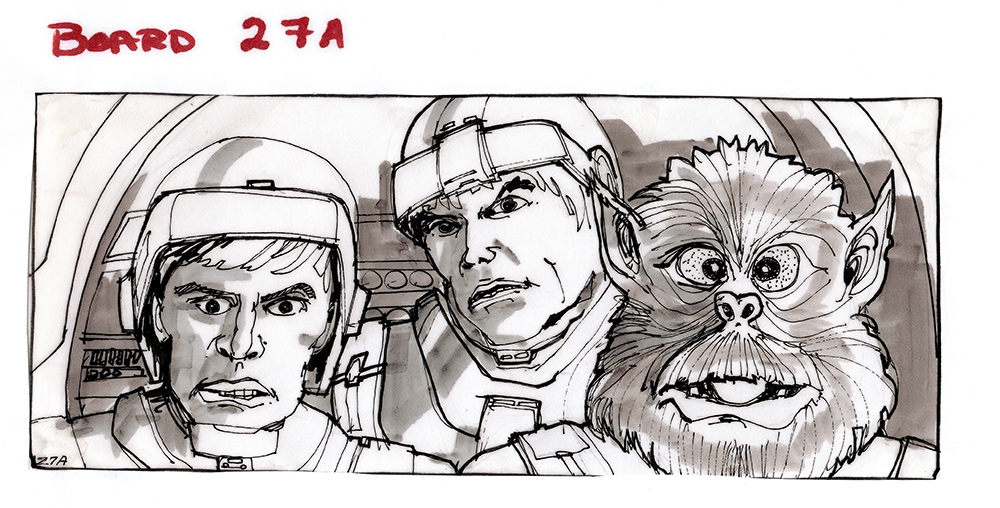

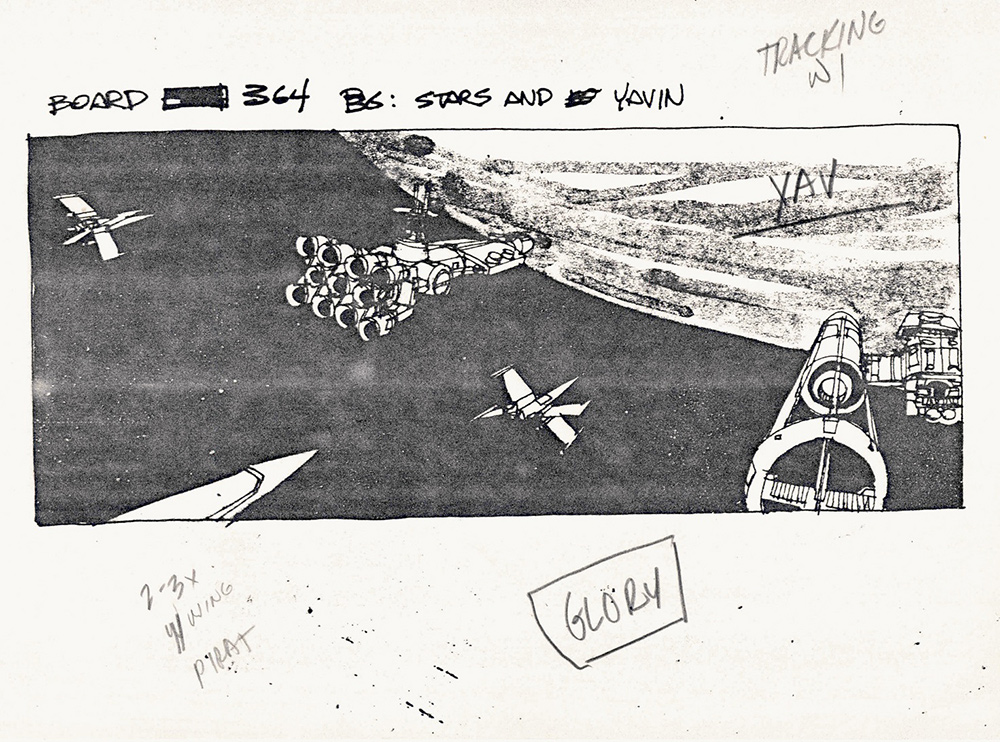

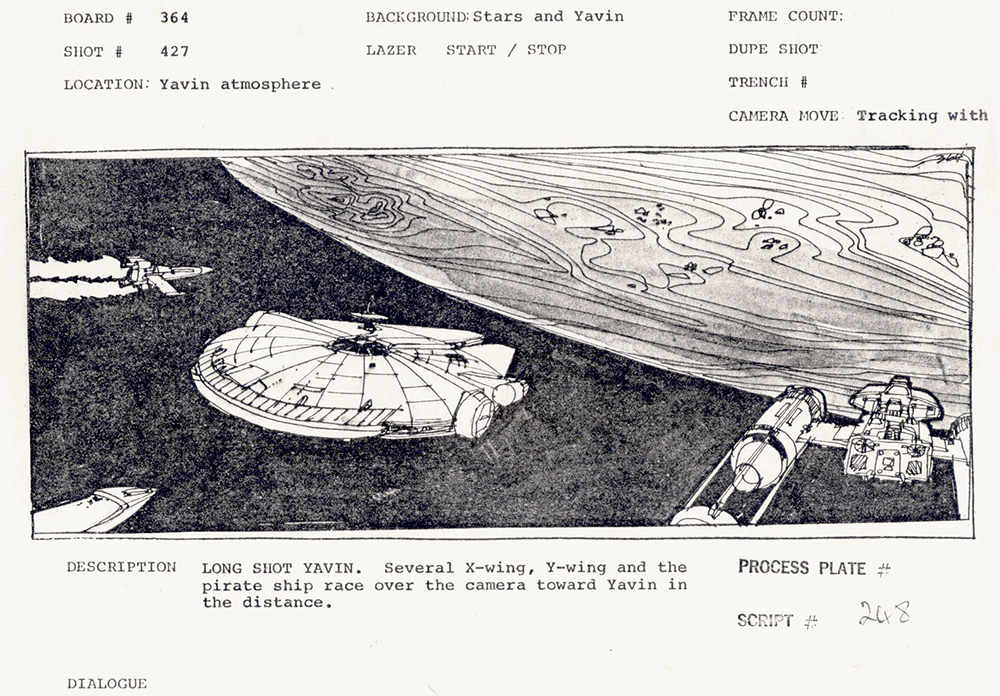

Early storyboards also made use of Cantwell’s rebel ship and pirate ship, and reveal Richard Edlund’s technical notations.

Johnston’s Leia is drawn from Tavoularis’s interpretations of the princess.

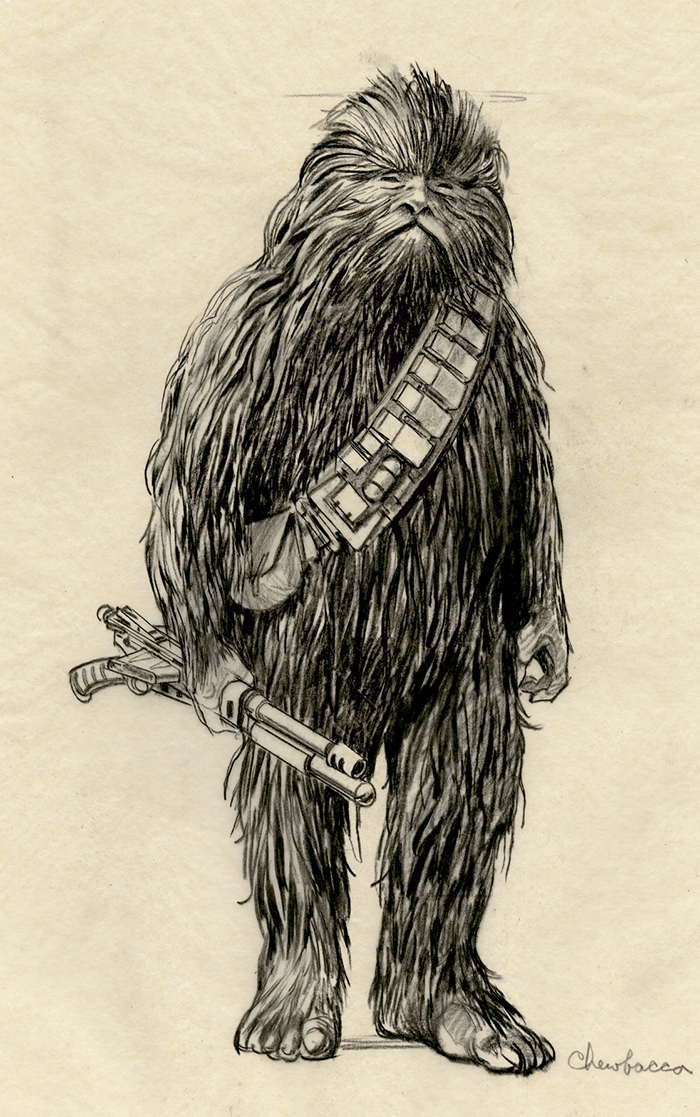

Johnston storyboarded with Rapidograph pens and gray felt markers in black-and-white and shades of gray on Canson Vidalon tracing vellum. Early boards incorporated McQuarrie’s early take on Chewbacca, which he subsequently revised.

Hundreds of location shots were taken during the recces to Tunisia, which then served as inspiration for John Barry’s production design sketches, one of which reads, “Djerba Hotel, Tatanouine,” which became “Tatooine.”

Barry’s sketch of the city of Chebika is marked “alternative town to Aj im near Salt Flat location.”

The homestead sketch is identified as being on the Salt Lake, Tozeur, Tunisia.

Barry’s sketch of the bones, with a tiny R2, is dated 1975

“Ralph’s illustrations became a focus for everyone involved in the visual work,” he adds. “There was no question that we were trying to achieve some part of the direction that Ralph was showing there in his illustrations. It unified the whole facility. And then he’s such a nice, gentle man, it was just really a revelation to meet him.”

“He’s real quiet, but he’s really fun underneath,” Dykstra says. “There’s a whole bunch of stuff going on in Ralph’s mind all of the time.”

“I think McQuarrie’s paintings are why the movie’s taken the shape it has,” John Stears also remarked in England, “because those sketches are so specific. They’re beautiful.”

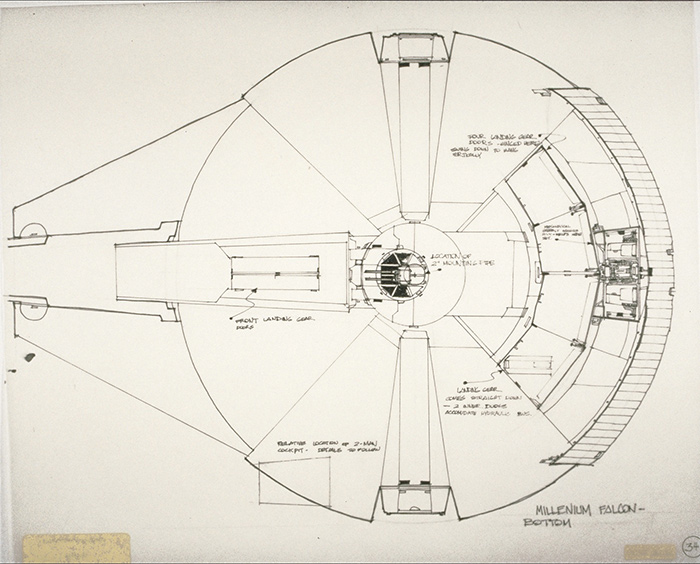

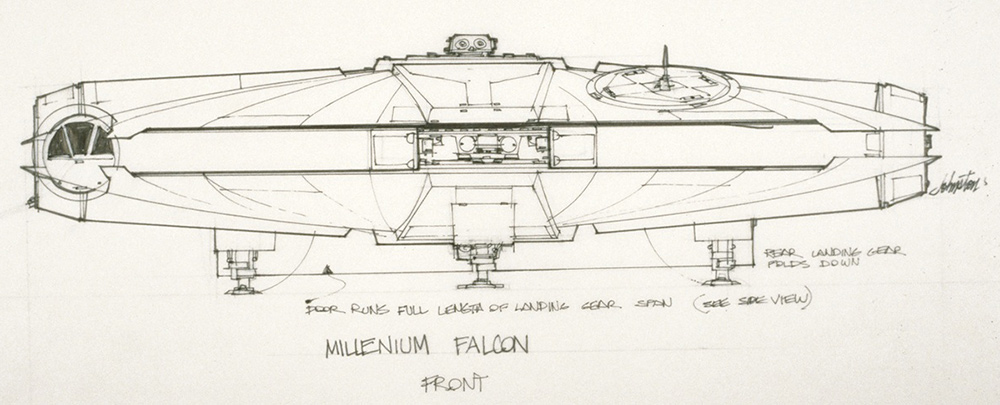

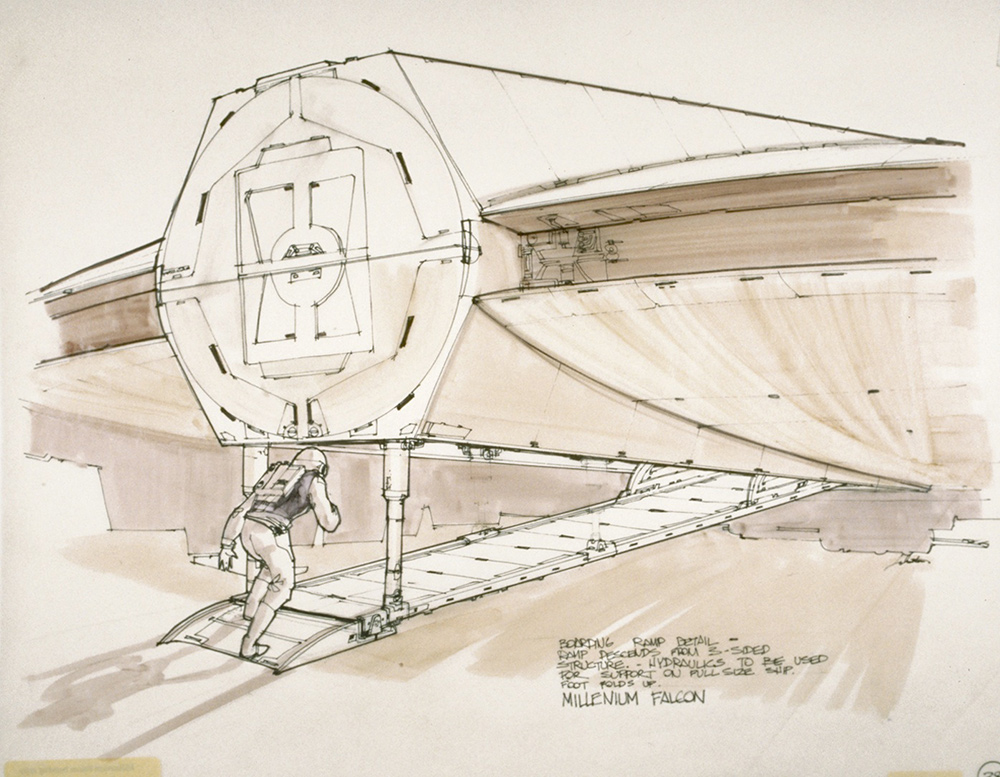

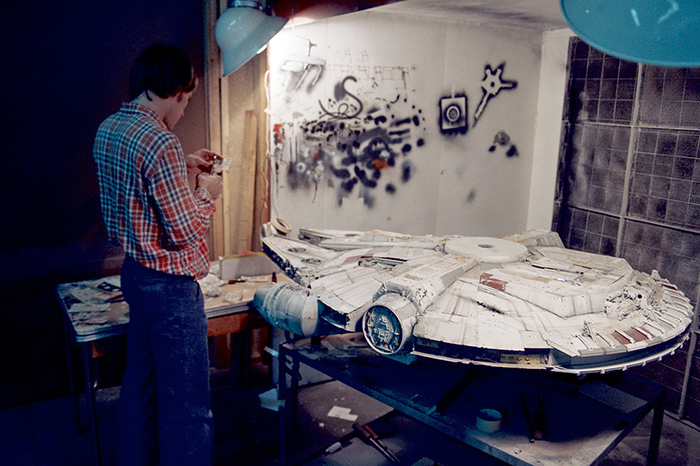

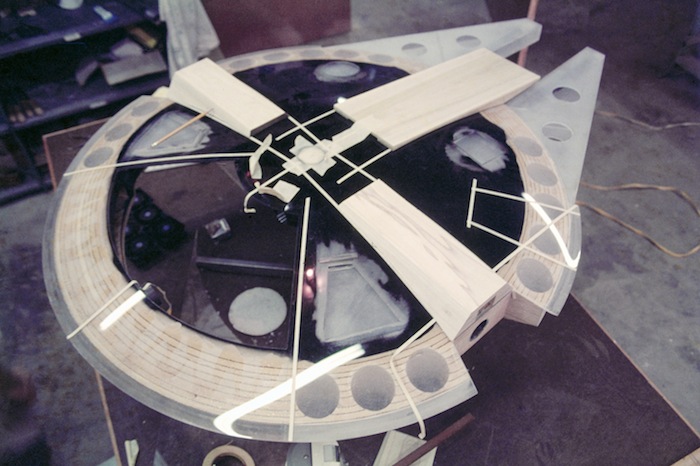

Lucas’s return from London also gave renewed urgency to ILM’s model shop. Three key ships had to be finalized so that full-scale sets could be built based on certain portions of the miniatures: An interior and partial exterior were to be constructed for the sandcrawler; hallways had to be built for the rebel ship; for the pirate vessel, a cockpit, a central area, gunports, and a partial but massive exterior were in the works. “ILM would do a sketch and then they would do a preliminary blueprint,” Lucas says. “Then they’d build a little model, which we’d look at later in England while we were doing the big blueprints, which were for the construction people. At each stage, I would have to look at it first and approve it.”

As they soldiered on despite Fox’s moratorium, the situation had become even more complex because Han Solo needed new “wheels.” A television series called Space: 1999 had debuted earlier that year, and Lucas found that its main ship looked too much like the first pirate ship—which the model makers had finished literally the weekend before they heard. “They were all very upset that I changed the design, ’cause they had just finished building the other pirate starship,” Lucas says. “They had spent an enormous amount of money and time building that other ship, and I threw it out. It’s one of those decisions that was very costly, but I felt that we really needed the individuality and personality of a better ship.”

The exact cost of the first pirate ship is difficult to ascertain, because, according to McCune, “it got billed for everything,” but a rough estimate would be around $25,000—about a third of the total budget for the models. “It was seven feet long and had four hundred cycles of electronics going through it,” he says. So instead of scrapping it completely, that ship became the rebel ship, which was only in a couple of shots, while the vessel with more screen time was redesigned. “Joe, George, and John worked up this new idea for what they called the round ‘Porkburger,’ ” McCune laughs.

“The flying hamburger was my favorite design,” Lucas says. “I thought that the other design was too close to Space: 1999 and too conventional looking. I wanted something really off the wall, since it was the key ship in the movie; I wanted something with a lot more personality. I thought of the design on the airplane, flying back from London: a hamburger. I didn’t want it to be a flying saucer, but I wanted to have something with a radial shape that would be completely different from anything else.”

The ship, by necessity, quickly took form. “The pirate ship was a highly modified smuggler’s freighter,” Johnston says. “George wanted it to look like it’d been hot-rodded, so we put bigger engines on it and stripped things off of it. He also liked the idea of having a double inverted saucer shape. So I did a series of saucer shapes, freighters, spaceships—and one of them was very similar to how the ship ended up. I think mine had the cockpit in the center on the top instead of being on the side.

“The second pirate ship was probably the ship we designed the fastest,” he adds. “It probably took less than a week.”

So speedily was the design approved and building started that, because Lucas liked the look of the first pirate ship’s cockpit, it was simply transferred to the new pirate ship, creating an aesthetically pleasing nonsymmetrical design. “We didn’t have time to generate a new fancy cockpit for the pirate ship so we just sawed it off the first ship and stuck it on there,” McCune says.

The rebel ship was now without a cockpit, “so George and Joe came up real quick with this hammerhead shark idea. That was simply two cardboard buckets filled with Styrofoam and paper peeled off and dug out and covered with styrene and model parts, just to solve the problem right away,” McCune adds.

All this activity at ILM meant that the facility had to again hire more people. Some were art or industrial design students (many from Long Beach State University), some were “high school or college dropouts or burnouts who knew how to run an electric drill,” according to Shepherd, while a couple were hired thanks to their unique skills. Jon Erland and Lorne Peterson, who started on December 8, were known to be experts at making very complex rubber molds. “I hired those guys,” Shepherd says. “In fact, almost all the people in the model shop, with the exception of Grant McCune, were people that I scrounged up wherever we could find them. People who knew how to build miniatures, who understood new processes and new plastics. Grant wanted people with ‘mental chutzpah.’ He wanted them to be able to think a problem through and also be very good with their hands.”

“Bob Shepherd and I knew each other from living in Seal Beach,” Lorne Peterson says. “He asked, ‘Do you wanna help out?’ It was a science-fiction film, but I had no idea what kind of science-fiction film … I think when I started there were thirty-some people.”

“Jon and Lorne came on just about the time we were starting to make the Death Star molds,” Grant McCune says. “They both had a lot of experience—and they’re the ones who saved our asses, because we were still at a point where we were experimenting with materials. When Jon and Lorne came, they knew the latest ways of mold making and pattern making; that’s when we got the vacuum former and the injection molder. That’s how we were able to produce the number of models that they needed for the explosions and things like that. I would say that those two guys really saved it.”

“The rest of the crew developed in strange ways,” Richard Edlund adds. “Doug Smith, who turned out to be my right-hand man, started out sweeping the floors.”

Joe Johnston did several sketches of the second pirate ship. Because a hamburger or saucer doesn’t really have a front, mandibles were added to give the new vessel orientation. “We justified the mandibles by saying that they could be a freight-loading area where your cargo goes in,” Johnston says. “Something comes out and grabs the freight and takes it back into the ship.”

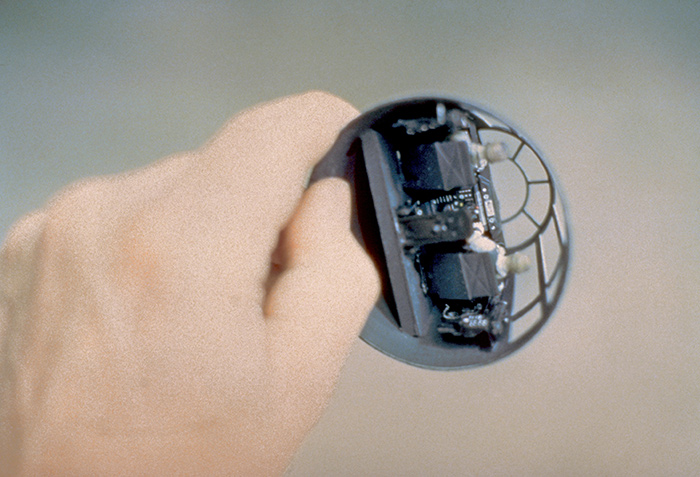

The cockpit was lifted off the first pirate ship.

On December 13, 1975, Fox had its long-awaited board of directors meeting. The fate of The Star Wars hung in the balance—at least for the studio. Lucas was fully prepared to take his project elsewhere if necessary. A participant at the crucial meeting, Warren Hellman says, “To the best of my recollection, Laddie came in and said, ‘I’m a believer in this—we’ve gotta go ahead with this project. Now’s the time we really have to get behind this.’ Dennis Stanfill was being neutral, and finally went along with it. But the board never had enthusiasm for the project.”

It was decided to give the film the green light. Though each board member had been given a portfolio made by Lippincott containing artwork by Ralph McQuarrie and Joe Johnston, according to Hellman, Ladd’s backing was the key. At least one letter written by Pollock makes it clear that the Star Wars Corporation was aware of this: “George Lucas is extremely pleased with his relationship with Alan Ladd Jr.”

“I would have loved to have been at that meeting with Laddie’s board of directors,” says Michael Gruskoff, one of the producers of Lucky Lady, “when he presented Star Wars as a $7 million movie with a small furry animal and two robots, with the budget constantly going up and just a few sketches to show—and he needed an answer right then.”

“If at any time, Laddie would have left, the project would have died. There is no doubt,” Pollock adds.

“Kubrick’s 2001 didn’t break even until late 1975—and that was the most successful science-fiction film of all time,” Lippincott says of the 1968 release. “You had to be crazy to make a science-fiction film when we wanted to.”

Another letter, written shortly after the board meeting, expressed concern over a possible management change—Fox was still on treacherous financial ground—asking for assurances that if Ladd were to leave the company, Lucas would have final cut. “Unfortunately, after some negative experiences in the past at other studios, George does not feel that he can entrust the product of four years of his life to an unknown person,” Pollock wrote to Immerman on January 5, 1976. “George feels very strongly about this point—as strongly as about anything else we have ever discussed.” The reply was that, as a publicly held company, Fox could not grant final cut.

But Lucas’s space fantasy was a go-project and the purse strings began to loosen. From then on, everything from casting to set building to special effects jolted back to life and quickly took up a truly frenetic pace. On December 17 Lucas was interviewed by Lippincott, perhaps to mark the occasion of the critical point that had been reached after two and a half years of work:

George Lucas (Lucas): I’ll talk about anything.

Charles Lippincott (Chas): Why did you write this story, The Star Wars?

Lucas: Well, I read a lot of books, including Flash Gordon. I loved it when it was a movie serial on television; the original Universal serial was on television at 6:15 PM every day, and I was just crazy about it. I’ve always had a fascination for space adventure, romantic adventures. And after I finished Graffiti, I came to realize that there were very few films being made for young people between the ages of twelve and twenty. When I was that age, practically all the movies were made for that age. I realized that since the Western had died, there hadn’t been any mythological fantasy movies available to young people like the ones I grew up on: Westerns and pirate movies, Errol Flynn, all that. They just sort of petered out to the point where they don’t do them anymore, and then it petered out on television. Now all you get is cops and hard drama. So instead of making important, gripping, isn’t-it-terrible-what’s-happening-to-mankind movies, which is what I started out doing, I decided it would be much more useful for me to make movies that made kids have a fantasy life and feel good, so they could go ahead and have a more productive life.

John Barry and Lucas study topography photos of Tunisia, in England.

Lorne Peterson in the ILM model shop.

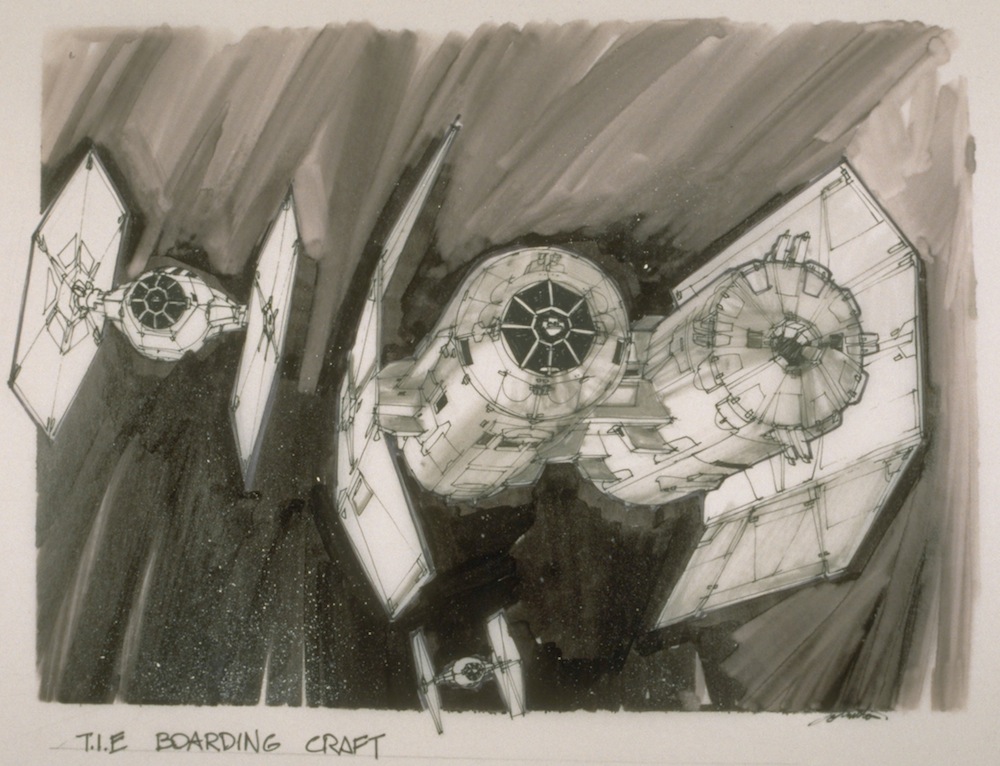

Concept art of a TIE fighter and “boarding craft,” by Joe Johnston.

Lorne Peterson.

Chas: The Star Wars has been through quite a few conceptual changes, there’s been several scripts—what was the evolution?

Lucas: Well, the problem is what happens in a lot of movies. It started as a concept. So I want to make a movie in outer space, let’s say an action-adventure movie just like Flash Gordon used to be. People running around in spaceships, shooting each other, and exotic people and exotic locations, and an Empire. I knew I wanted to have a big battle in outer space, a dogfight, so that’s what I started with. Then I asked myself, What story can I tell? So I was looking for a story for a long time. I went through several stories, trying to find the one that was right, that would have enough personality, tell the story I wanted to tell, be entertaining, and, at the same time, include all the action-adventure aspects that I wanted. That’s really where the evolution came from: Each story was a totally different story about totally different characters before I finally landed on the story. A lot of the scripts have the same scenes in them. On the second script I pilfered some of the scenes from the first script, and I kept doing it until I finally got the final script—which is the one I’m working on now—which has everything from all the other scripts that I wanted. Now what I’m doing in this rewrite is I’m slowly shaving down the plot so it seems to work within the context of everything I wanted to include. After that, I’ll go through and do another rewrite, which will develop the dialogue and the characters.

Chas: Do you conceive of a scene you would like to do in a certain setting and then…

Lucas: This film has been murder. It’s very easy to write about something you know about and you’ve lived through—it’s very hard to write about something you make up from scratch. And the problem was that there was so much I could include—it was like being in a candy store, and it was hard to not get a stomachache from the whole experience. But there were things I knew I didn’t want to have, like exposition. I wanted the story to be very natural. I wanted it to be more of a straight adventure movie rather than something that had such complex technology that most of the film was spent dealing with the technology. And I didn’t want to make it so obscure that you didn’t understand what was going on at any given point—which is very hard to do in a science-fiction/fantasy movie, because everything is unfamiliar and therefore, by definition, needs to be explained.

Chas: How did you conceive of the characters?

Lucas: My original idea was to make a movie about an old man and a kid, who have a teacher-student relationship [treatment, rough, and first drafts]. And I knew I wanted the old man to be a real old man, but also a warrior. In the original script the old man was the hero. I wanted to have a seventy-five-year-old Clint Eastwood. I liked that idea. Then I wrote another script without the old man. I decided I wanted to do it about kids. I found the kid character more interesting than the old man. I don’t know that much about old people and it was very hard for me to cope with it. So I ended up writing the kid better than the old man. Then I had a story about the kid and his brother, where the kid developed—and a pirate character developed out of the brother [second draft]. As I kept writing scripts, more characters evolved. Over the two-year period of rewriting, rewriting, rewriting, all the characters evolved. I pulled one character from one script and another character from another script, and pretty soon they got into the dirty half dozen that they are today. It was a long, painful struggle, and I’m still doing it, still struggling to get them to come alive.

Chas: What point have you been trying to reach with them now?

Lucas: Essentially, I’m trying to knock out all the plot loopholes and I’m trying to smooth it out and add more intensity to the film, make it work better. I’m trying to make the characters more interesting, more enjoyable.

Chas: Your films, even when you were working as a student, always have been strongly oriented toward design, a strong visual sense. How did you conceive of the visuals in this film?

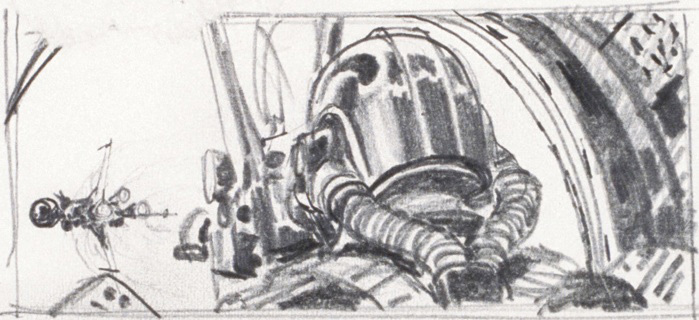

Johnston’s story-boards with Edlund’s notes reflect the pirate ship design revision. An earlier shot of the ship approaching Yavin (above) is replaced with the second vessel (below).

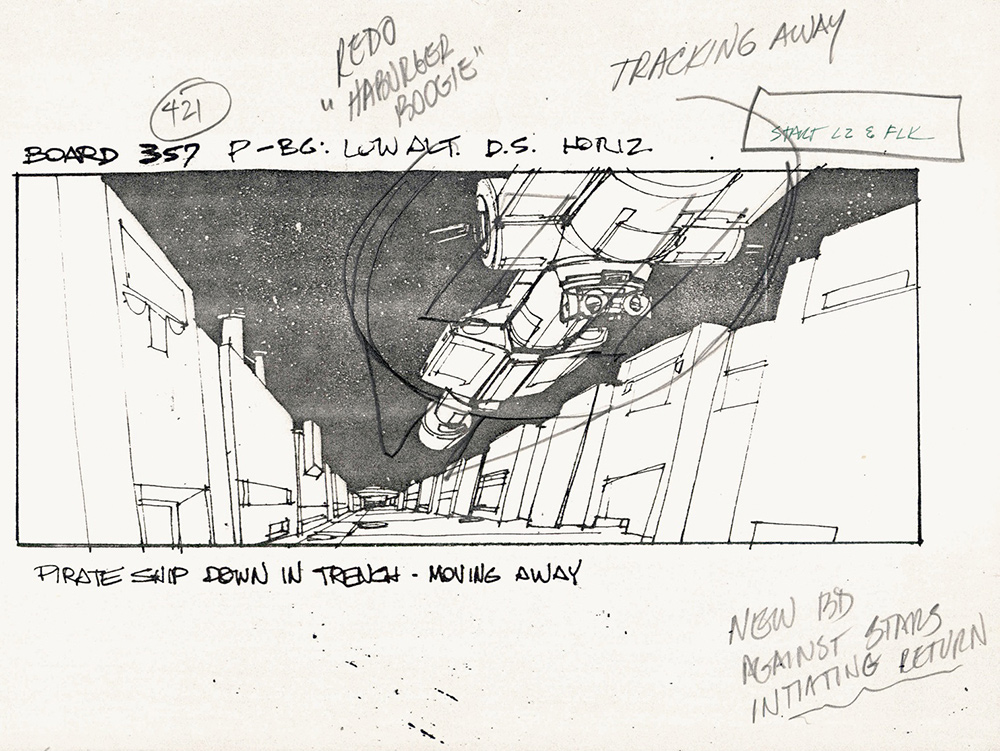

Storyboard showing the first pirate ship moving along the Death Star trench. “Re-do ‘Hamburger Boogie’ ” is a notation referring to the second pirate ship, which had been inspired by the form of a hamburger.

Lucas: I’m trying to make a film that looks very real, with a nitty-gritty feel, which is hard to do in a film that is essentially a fantasy. Photographically, I’m working on a filtered look, nostalgic, a looking-back quality. I’m using a lighting style that is very dramatic, in the style of Greg Toland [the cinematographer on Citizen Kane, 1941; and My Darling Clementine, 1946], using strong shadows. Framing-wise, I’m going to try for a semi-documentary, loose frame that will give it a nervous “now” quality, a sense of being captured, which will look real but at the same time be slightly fantastic. Binding all those things together will create, hopefully, a fantasy-documentary look.

Chas: You’ve had a strong orientation toward documentary. Your first two features used documentary cameramen. Why?

Lucas: I have a strong feeling about it. I like cinema verité; it’s one of my real loves. Cinema verité films are challenging, and that whole genre is in my blood. Apocalypse Now was going to be a real Peter Watkins [famed BBC documentarian and Academy Award winner], you-are-there, newsreel-type movie. Ultimately, the genre of the movie you’re making determines the style that you have to use, and I’m a strong believer in style. Graffiti had a real Sam Katzman, AIP [American International Pictures], hot-rod movie style, and everything was sitting there center frame. THX was a totally two-dimensional drawn-on, surreal style, with very eccentric graphics and framing—but it also had that documentary quality, which I achieved mainly through the lighting. In this film I’m going to use a documentary frame but with theatrical lighting. I like to have that edge of reality because I want the movies to make you believe they are real. I try to do it with the acting, too.

Chas: What is happening with the acting?

Lucas: It’s more improvisational and linked to the style I use in directing, which is to have more than one camera and lead back away from the people, so that the actors essentially play the scenes themselves. The cameras are onlookers, and you aren’t right in there. People aren’t acting to cameras, people are acting to each other. I won’t really demand that they get the lines right. They can play as much as they want with what they’ve got, which makes for a much more casual, sometimes much more intense interaction between actors rather than just having every little piece be perfect and done to the camera.

Chas: What do you look for when casting?

Lucas: I look for magic. What else can I say? Besides being solid actors, I’m looking for somebody who has the personal and physical qualities that I want that character to have.

Chas: You were talking the other day about having two concepts of the characters…

Lucas: I’m essentially thinking of casting in two different directions. One is a little more serious, a little more realistic; the other is a little more fun, more goofy. Right now my first choice is to make it fairly serious, because I think it’ll be more fun that way. Because I think you have to have a very strong reality in a movie for people to really enjoy it, and the more serious characters will give it the stronger reality.

Chas: Have you had any luck with Alec Guinness?

Lucas: We’re negotiating.

Chas: Will you have the studio putting any weight on you?

Lucas: I hope not. It’s not likely. The big issue usually comes down to whether you have movie stars or not, and since I’m not having movie stars, I don’t think they would know one actor from another.

Chas: How did you get them to agree to that?

Lucas: It’s just something that was a given at the very beginning. I said, “I am not going to put movie stars in this movie.” It wouldn’t do me any good, because the film is a fantasy. If it’s a Robert Redford movie, it’s no longer a fantasy; it’s a Robert Redford movie and you lose the whole quality of the fantasy, which is the only commercial aspect of the film in the first place. In order to create a fantasy, you have to have unknowns. I’m a strong believer in that. Part of the charm of Graffiti was that you’d never seen any of those people before, except Ronnie Howard, and I sort of slipped by with that. But essentially it was all fresh talent who you’d never seen in the movies before. It has a quality of making it not be a movie where players are acting a part; it has a tendency to make you believe that these are the real characters.

Chas: How are you going about choosing the various personnel, like your cameraman?

Lucas: I keep track of whose work I like as I go to the movies. So I interviewed thirty or forty cameramen, whose work I admired, to see how I get along with them. It’s especially hard for me in picking a camera [director of photography], because I never had a camera before. I’ve more or less shot my own movies. On Graffiti, Haskell Wexler came in, and he’s a very close friend of mine. It was really just him helping me out; it wasn’t like having a DP on the picture. I’ve never really had that to contend with, so on this picture it’s been tricky. I’ve been trying to find somebody who will essentially work with me and do more or less what I want to do, the way I want to do it. I like to take a lot of chances, do a lot of very eccentric things—and finding somebody who is open-minded enough to take chances and not worry about whether it’s going to look good is very difficult. And this picture is going to be difficult, technically: It has a lot of front projection, a lot of huge sets lit with backdrops and paintings, and challenging stuff that a lot of younger men can’t handle because they’ve never done it. They shoot on location and they know a certain kind of lighting, but they don’t know the old-style giant-set-on-a-sound-stage lighting with backdrops and tricky cutouts.

Chas: What’s cameraman Gilbert Taylor like?

Lucas: He’s very free-thinking, very talented, will do anything. That’s originally what I was looking for. He’s very similar to Geoffrey Unsworth. I think he’s the best black-and-white cameraman in England. I’ve only had about two meetings with him; I don’t think he’s even read the script yet, quite frankly. Matter of fact, I’m sure he hasn’t. What it comes down to is: I have a tendency to want a lot of the control over it. A lot of the decisions will be made for him, and I will expect him to build on those decisions and make them come out the way I want them.

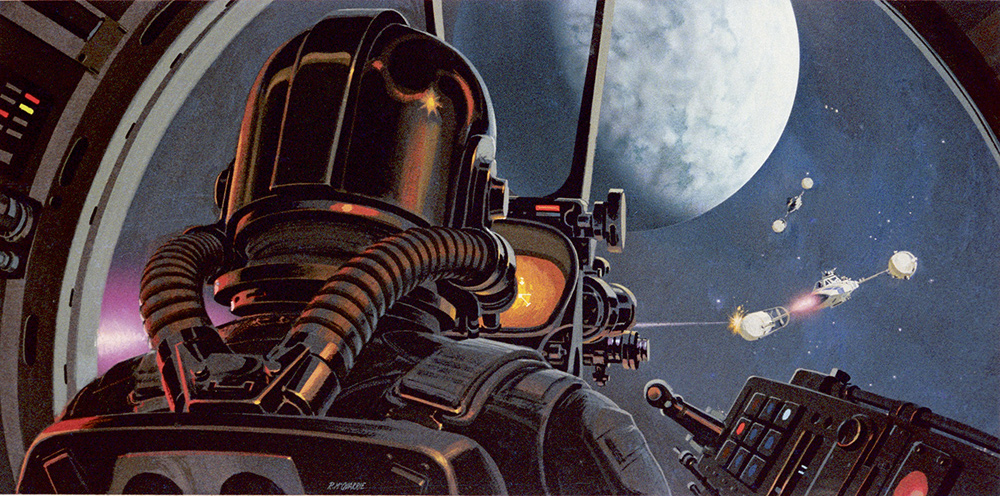

A series of images show how elastic a certain shot could be: what started as a McQuarrie sketch of an Imperial pilot tracking another ship …

…became a Tavoularis storyboard of the same pilot approaching the cloud city of Alderaan …

…which became a McQuarrie painting of a Y-wing as it flew toward a planet (possibly Yavin) …

…which became the Colin Cantwell Death Star …

…which finally became another revised McQuarrie painting of the same pilot following the redesigned pirate ship approaching a redesigned Death Star.

Chas: Are you open to suggestion?

Lucas: Yeah, more or less; less than more, I’m afraid. Up till now the movies I’ve made have been my own movies; they’ve been very small and I’ve been able to handle everything. This is the first time I’m going to have to deal with a real crew in a real movie in a real professional situation. I want to be able to call all the shots, but I’m going to have to be slightly removed from a lot of what’s happening. That’ll be interesting. But I think I’m ready for it. I’ve loosened up a little bit. As you get older, you get tired more quickly. It’s more fun to have other people make suggestions, so you don’t have to do all the work.

Chas: Considering that this is a film that takes place in another galaxy, possibly in another time, where there’s been no contact with Earth, how are you going about designing things as simple as eating utensils?

Lucas: I’m trying to make props that don’t stand out. I’m trying to make everything look very natural, a casual almost I’ve-seen-this-before look. You see it in the paintings we’ve had done, especially the one that Ralph McQuarrie did of the banthas. You look at that painting of the Tusken Raiders and the banthas, and you say, ‘Oh yeah, Bedouins …’ Then you look at it some more and say, ‘Wait a minute, that’s not right. Those aren’t Bedouins, and what are those creatures back there?’ Like the X-wing and TIE fighter battle, you say, ‘I’ve seen that, it’s World War II—but wait a minute—that isn’t any kind of jet I’ve ever seen before.’ I want the whole film to have that quality! It’s a very hard thing to come by, because it should look very familiar but at the same time not be familiar at all.

Chas: How are you going about that with the various people you work with?

Lucas: I keep saying, ‘Keep it nondescript.’ I say that every time, every place I can. It can be a computer, but it’s got to be a nondescript computer. I don’t want anything to stand out. I don’t want any of the costumes, any of the spaceships, any sets, any animals—I don’t want anything in the movie to stand out. I want you to walk out of the movie and if somebody asks you what were they wearing, I want you to say, ‘I can’t remember what they were wearing. I can’t remember what the sets were like.’ If they ask, ‘What did the ray guns look like?’ You’d say, ‘I don’t know—they just looked like ray guns.’ If the whole movie looks like that, it’ll be terrific. It’ll be absolutely the opposite of what all the science-fiction movies are. With every other science-fiction movie, you remember what every set looks like, you know exactly the costumes they were wearing—because it all stands out and it all looks like it’s been designed. I’m working very hard to keep everything nonsymmetrical. Nothing looks like it belongs with anything else. You walk into a set and there’s lots of different influences, not just one influence. It’s a very common thing in science fiction to see a set that has one influence. Everything matches. The chairs match the table, match the rug, match the design of the doors, match the door handle, match the lamps. I want it to look like one thing came from one part of the galaxy and another thing came from another part of the galaxy.

After Alderaan’s scenes had been moved to the Death Star, and following the pirate ship redo, McQuarrie updated his paintings to include the new vessel and starfields instead of clouds outside the docking bay.

Chas: How’d you go about choosing your composer, John Williams?

Lucas: I’d heard that he was a very good classical composer, very easy to work with. I liked what he had done with Steve [Spielberg], who recommended him very highly and he thought I should talk to him. So I did and we got along very well, so I decided to hire him. I really knew the kind of sound I wanted. I knew I wanted an old-fashioned, romantic movie score, and I knew he was very good with large orchestras.

Early storyboards by Joe Johnston show Imperial officers in helmets firing at the second pirate ship as it tries to leave Alderaan/the Death Star (the model has changed, but the sky, instead of stars, can still be seen outside).

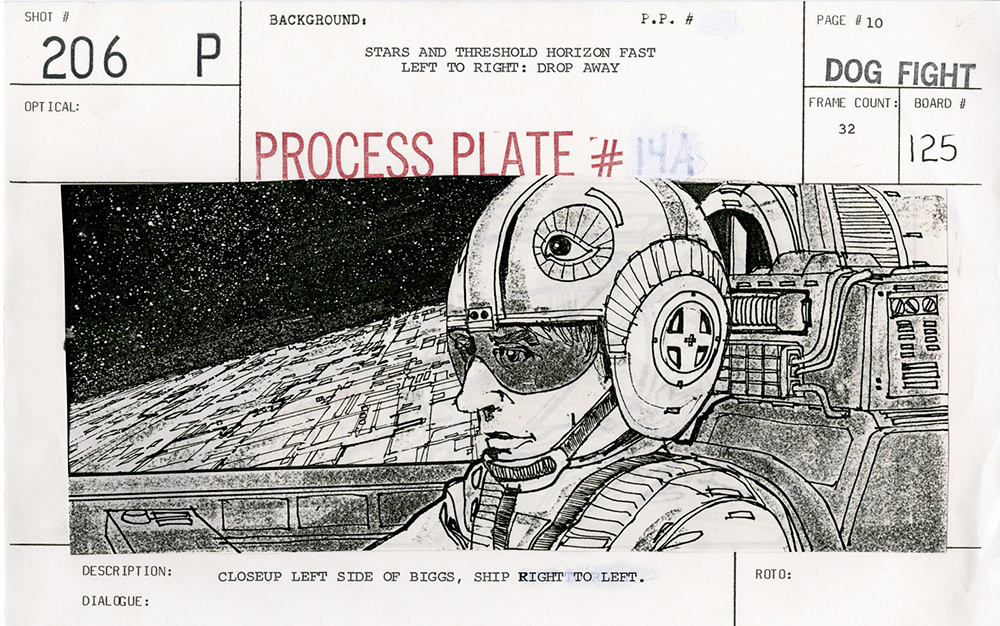

Rebel pilot Biggs wears a helmet with an Egyptian-style all-seeing-eye emblem in a storyboard intended as a guide for front projection “Process Plate #14A.”

Chas: Any particular scores you’ve liked by him?

Lucas: I liked Jaws [which had been released on June 20, 1975, and become a mega-hit].

Chas: How are you treating the musicians in the cantina? You’ve talked about a different type of music for that…

Lucas: It will be a very bizarre, kind of primitive rock. I’m toying with the idea of adding a country-and-western influence to the film, combining country and western with classical. If I can get away with it, I might do it.

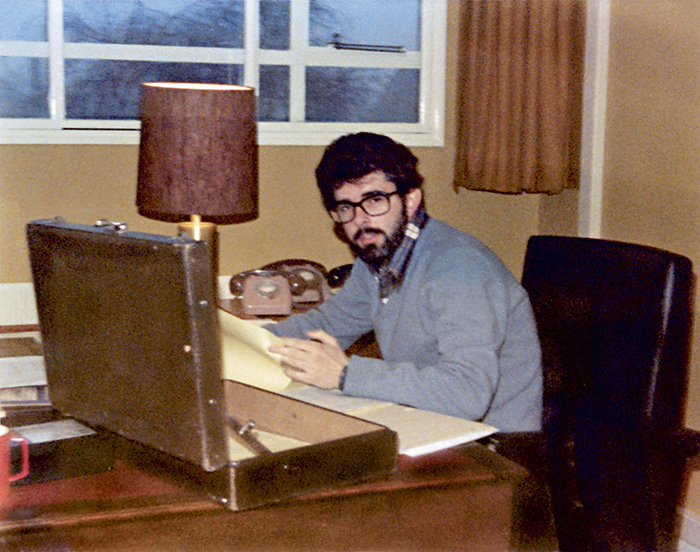

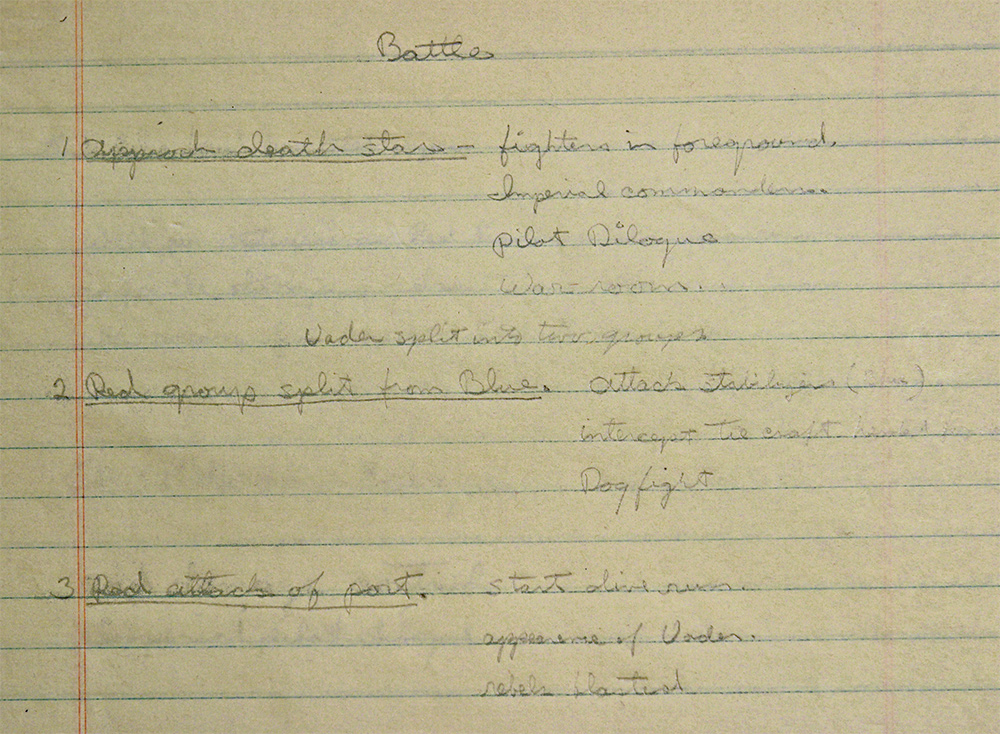

Just before and after Fox’s decision, Lucas attended casting sessions while in Los Angeles. Between sessions, ILM needed more attention—but before showing up at Goldwyn Studios or at Van Nuys, rising before dawn as he had while writing THX 1138, Lucas was busy hammering out the fourth draft. In particular, he was honing the end battle, which ILM needed to get a jump on.

“It wasn’t until the fourth draft that I described the dogfight in detail,” Lucas says. “What I did each time before that, as I finished the draft, was think to myself, This is not the final script, and then write, ‘There is this big battle and Luke wins.’ But now I had to really work it all out. Some of the details had been sketched in, so I took those and expanded them. I would also consult the World War II footage I’d cut together, and the storyboards that had been made in conjunction with the edited film, and just write the story and then restructure it like an editor would. It was almost like making a documentary film, in that I cut it and wrote it at exactly the same time. That seven minutes of film time, when it was translated shot by shot, became about fifty pages of the script, because each shot was described in detail.”

On December 17 Lucas explained to Lippincott: “I have to do twenty-five boards [shot descriptions] a day, so I’m getting up at three o’clock in the morning to start the twenty-five—but I have to get them done by nine o’clock in the morning. The casting and testing I can’t show up late for, but every time I go out to ILM, I end up going out there at nine o’clock instead of eight o’clock because of the fact that I can’t leave until I finish my twenty-five boards.”

Lucas inspects the second pirate ship construction at ILM with Bill Shourt (next to the core of the vessel).

Lucas with Bill Shourt and Jamie Shourt

Later Joe Johnston works on the ship’s paint job, inside the spray booth.

Paul Huston and model maker David Grell work on the Falcon model.

Handwritten notes reveal that one of the rebel pilots, “Chewie”—a leftover from previous drafts—was going to be one of the few to survive: “Chewie: ‘Here we go again … I’ve got a malfunction, Luke … I can’t stay with you … You did it! You did it! They went right in!’ ” But with Chewie becoming the nickname of Chewbacca, Solo’s copilot in the fourth draft, rebel pilot Chewie became rebel pilot Wedge. Solo’s end heroics were also solidified in Lucas’s notes: “Full shot of wingman POV. Out of the sun charges Han Solo, in his pirate manta-ship heading right for the TIE ships.”

Rushing to ILM with his pages in hand, Lucas would then consult with Dykstra and Johnston on the impending front projection plates, after which he’d review the model makers’ progress on the essential miniatures. Immediately upon Lucas’s approval of Johnston’s new pirate ship sketch, Steve Gawley had done the orthographic drawings, and the model-building crew had started work that continued through Christmas and New Year’s, coming in Sunday nights at four in the morning to take pieces out of molds so that they would be ready for Monday-morning revisions.

“Joe Johnston and I actually carpooled from Long Beach to Van Nuys every day,” Gawley says. “It was like 124 miles round-trip every day, but we were thrilled as can be to be working on something this cool. Though the distance sometimes did get in the way—you know, you’d be working late so that it wouldn’t pay to drive home, so we’d sleep over in the screening room.”

That excitement must have carried over into the creation of the new pirate ship, building a palpable sense of pride in the work, because all eleven artists who had a part in it signed their names on the finished model.

Lucas arrived, on time, for at least three casting sessions—December 12, 15, and 30—as videotape still exists for those meetings. Among the tested were, on the first day, Kurt Russell, Patti d’Arbanville, Richard Doran, and Terri Nunn; on the second day, Kurt Russell (again), Chris Moe, Forest Williams, Amy Irving, Christopher Allport, Terri Nunn (again), and Will Seltzer; and on the third day, Terri Nunn (for the third time), Lisa Eilbacher, Robby Benson, Eddie Benton, Linda Purl, Andy Stevens, Mark Hamill, and Carrie Fisher.

Newcomer Harrison Ford was present all three days. While most tests were for the Luke and Leia parts, with Nunn clearly the front-runner for the latter, Ford was called upon to read Han Solo’s lines for each tryout. According to Ford, he was asked to read with the others thanks to Fred Roos, who had helped persuade Lucas to amend his policy of not considering any actors who’d appeared in American Graffiti. The long and inconclusive first casting session had also changed matters, as both Cindy Williams and Charles Martin Smith—like Ford, Graffiti veterans—were also allowed to test.

Roos also went so far as to “cast” Ford in a staged performance for Lucas’s benefit, which happened to include another Graffiti stalwart, Richard Dreyfuss. Roos had long ago cast Ford in one of his first parts—a political activist in Zabriskie Point (1970), a role that was eventually cut from the film—and he seems to have had an ongoing concern for the struggling actor’s welfare.

“I left acting to become a carpenter because our second baby was coming and we like to eat,” Ford says. “I wasn’t making it as an actor.”

Because the sessions were being held at the American Zoetrope offices, Roos “hired” Ford, who was also a skilled carpenter, to install a door there—precisely when he knew Lucas would be coming by. “Getting George to consider Harrison took some working around,” Roos says.

“I was out there kneeling down in the hall, putting up this elaborate doorway,” Ford says. “Dreyfuss, the big movie star, came in to see George for the picture, and there I was cast as the blue-collar worker. That was the only time I saw George, not more than three or four weeks before they were set to make a decision.”

The ploy worked, according to Roos: “It just kind of clicked for George at that point.”

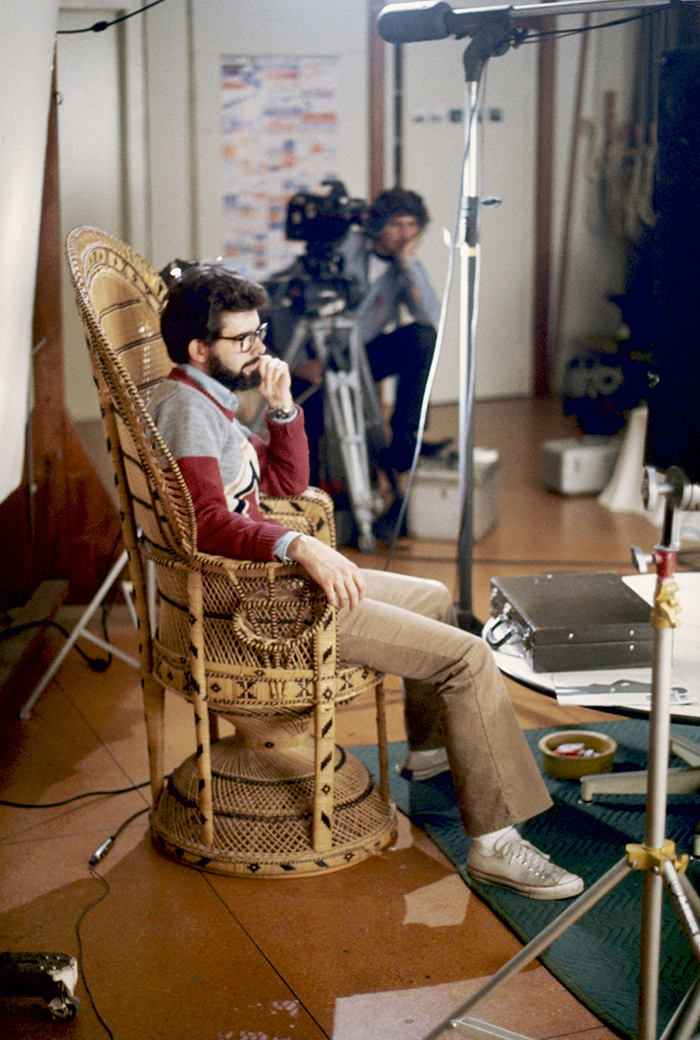

Lucas during the second casting session in December 1975.

“I thought, Here’s a possibility,” Lucas says. “Harrison was right for the part, so Fred suggested he read with everybody, which I thought was a great idea—but I wasn’t going to commit. I wanted someone just like Harrison, but not Harrison, because he was in Graffiti and I didn’t want people thinking of another film while watching Star Wars—I wanted it to be new. But Fred liked to help actors survive and was giving him work, and was pushing for him for that part. But I had to go through the whole process. I wasn’t going to take anyone just because I knew them, or I knew they could act well—I really wanted to see all the diverse possibilities and come at it fresh. Plus, I wasn’t going to choose anyone until I’d tested the whole cast together.”

“I think I did fifty or sixty tests for them—testing other people,” says Ford, continuing the story. “I was asked to help them test other people. The test was offered, pretty much, without explanation. Many times, I was asked to explain to the testees what the story was about, or George would offer a very simple explanation—that there was this farm boy sent off to the big city, who got involved in this adventure. Then we’d read the scene. But there were not very many people who were not hung up on that level of it. It was a very difficult situation for most of them.”

The cursory summaries were the result of Lucas’s desire simply to see these candidates on-screen; their understanding of the situation mattered little compared with their performance’s unpredictable chemical reaction to the video and film stocks on which they were being recorded.

“I have them do readings, then videotape tests, then film tests,” Lucas says. “Each time, I weed people out. By the time I get down to an actual film test, I’ve really gotten to know that person. I’ve gotten to know their acting ability and all the ramifications of their personality. Because you have one impression when you meet somebody for five minutes and another impression when you call them back and talk to them for half an hour—and then you have another impression when they’ve played the scene on tape and you can sit back in a room and study it on television.”

In addition to the actors, calls had gone out for “little people and giants,” according to Dianne Crittenden, whose assistants used “breakdown services” to send letters to every agent in town; she also put ads in the trade papers. As he had during the first casting sessions, Lucas was contemplating a different tack, this time playing with the idea of doing the film almost entirely with little people—according to Lippincott, “rewriting the whole film for midgets.”

“When I was in New York, I had also done some screen tests for little people,” Lucas says. “I explored all kinds of ideas of making it exotic. I think that idea was a little influenced by Lord of the Rings.”

While that concept was ultimately short-lived, Lucas had not forgotten his idea of casting a black Han Solo, Ford notwithstanding. As all these ideas fought for dominance in his mind, two dark-horse actors arrived for their videotape tests on December 30: Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher.

The dialogue chosen for those trying out for the Luke Starkiller role was originally written for Ben Kenobi. In the third draft he explains to Han Solo the financial situation after they’ve discovered that Organa Major has been destroyed, coercing him into helping rescue Princess Leia:

HAN

Why?

LUKE

Well, for one reason, we don’t have your other five thousand.

HAN

Who’s going to pay me then?

LUKE

I think there are some things we should talk about.

HAN

I’m beginning not to like you.

Video excerpts from the taped auditions: Lisa Eilbacher, Linda Purl, Eddie Benton, Cindy Williams, Carrie Fisher, Amy Irving, Perry King and Charles Martin Smith, Robby Benson, Mark Hamill, Kurt Russell, Frederic Forrest, Harrison Ford, Andrew Stevens, William Katt, and Will Seltzer.

Mark Hamill, though he’d made it this far, was anything but a shoo-in for the part. “George was open to re-seeing some of the people, like Mark, who he’d dismissed early on,” Crittenden says. “This is one place where Fred Roos came in, because Fred had worked with George before, so George respected him.”

“There was that one meeting,” Hamill recalls, “and then Christmas rolled around and I had forgotten about it completely. The next thing I heard, Nancy had gotten me a test with George, way out of nowhere. Four pages of dialogue. There was one great line, though, and it was the hardest piece of dialogue I’d ever memorized. I came about a half hour early to the test, memorizing this line the way you memorize ‘she sells sea shells by the seashore.’ And it was, ‘We can’t turn back. Fear is their greatest defense. I doubt if the actual security there is any greater than it was on Aquilae or Sullust. What there is, is most likely directed toward a large-scale assault.’ Who talks like that? But you’re selling it.”

Although perplexed by his lines, Hamill had actually followed the progress of the production since its beginning, reading about it in the “Films in Preparation” section of Variety. The young actor had even contacted his agent way back when to see if she could perhaps get him a walk-on role, because he was curious to learn how science-fiction films were made, such was their rarity.

“I was sitting in the outer offices with Harrison,” Hamill continues. “And he’s Harrison. And I was thinking, He seems real calm and everything. I asked him what he’d done, and he told me about Graffiti. So he knew George a little bit. We went in and sat down, and Harrison said, ‘Hi, George!’ and was so loose with him it made me feel good. I asked, ‘Is there anything you want to tell me about the scene?’ And George said, ‘No. Let’s just run through it.’ We did, and I asked, ‘Is there anything you want me to do differently?’ And George said, ‘No. Let’s shoot it.’ He was so unenthusiastic, I thought, Oh, well, it’s probably hopeless. We ran through it again with no stops, and he said, ‘Cut. Okay. Thank you. Harrison, can you stay a couple of minutes?’ And I thought, That’s it. I didn’t feel bad or disappointed. It was just a clean no-go.”

The daughter of Hollywood icons Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, Carrie Fisher was attending the Central School of Speech and Drama in London when she was first contacted in early December. “Carrie Fisher was a social friend of mine,” Fred Roos says. “George was about to cast another actress, but I kept urging him to meet Carrie and test her.”

“They called me in London to test with the first block of girls,” says Fisher, who had recently played a minor but notorious role in Shampoo (1975). “They wanted me to come home, but you can’t leave that school in the middle because it’s like doing a play, and we were just into final production.” Fisher took a rain check. “I thought I’d totally missed testing for it.”

Circumstances favored Fisher, however, and she was contacted again while at home in Los Angeles during her Christmas break. Like Hamill, she received her pages in advance. “Leia was unconscious a lot,” she says. “And I wanted to be unconscious; I have an affinity for unconsciousness. I thought I could play that very well. But I also wanted to be involved in all of it, with Wookiees, with the monsters in the cantina. I was caught by my mother and some of my family rehearsing it in my underwear. I would come out of the bathroom and say, ‘General Kenobi!’ My family thought I was crazy, because the dialogue was, ‘A battle station with enough firepower to destroy an entire system.’ ”

Her designated scene was the one in which Leia reveals the importance of what R2-D2 is carrying. “When we finally tested Carrie, we had the opportunity to soften her a little bit because she wore her hair pulled back straight and was dressed rather severely,” Crittenden says. “We added some makeup and had her wear something that was a little more feminine and younger looking. Carrie was very unique in that she was formidable for an eighteen-year-old. She had a tremendous amount of sophistication, so in fact the hardest thing to do was to get her to be young.”

“It was like they were doing an assembly line,” remembers Fisher, who had been told by Brian De Palma that Jodie Foster had the inside track. “That day I think they had ten or fifteen people. They had me do it a couple of different ways: conversational and then arch. They taped a rehearsal and they taped another one, and there was very little direction—and I thought, There is no way that I have it. I didn’t hear anything for about three weeks, so I thought, Well, I’m not going to get to have lunch with monsters.”

While Hamill and Fisher were counting themselves out, Harrison Ford was feeling optimistic. “It would come to me in different ways,” he notes. “Fred Roos would say, ‘Wow, you’re lookin’ real good.’ And Roos’s girlfriend would come over and squeeze my hand as I was leaving. That kind of thing. But not a word from George.”

Lucas and Hamill, with his “sides.”

Perhaps because Ford did so many tests, the film made more sense to him. “There are certain key lines with the characters: ‘Look, kid, I’ve been from one side of this galaxy to another and I’ve seen a lot of strange stuff—but nothing to make me believe that one all-powerful Force controls everything,’ ” says Ford. “Is that easy enough? It’s real easy the way George has it set up.”

The tests completed, Lucas prepared for a few last meetings at ILM and a long stay in England, while the actors went their separate ways.

“I saw Terri Nunn at the unemployment office a month later,” Hamill says. “She asked me, ‘Did you get it?’ I said, ‘No. Did you?’ She said, ‘No,’ and we embraced and that was the last I saw of her. Because I still didn’t know; I’d heard it was 80 percent sure someone else …”

Harrison Ford and Terri Nunn.

Frederic Forrest and Cindy Williams.