Budget cuts obliged Lucas to change the story considerably. The elimination of Alderaan and the moving of its scenes to the Death Star had the fortuitous effect of giving the bad guys a single location, eliminating many scenes, and concentrating the action into a more quickly moving story. However, the combined stresses of dealing with Fox, ILM, the art departments, and casting took their toll on the writer-director. “Essentially you are doing two jobs,” Lucas says. “If a director works ten hours a day, then a writer-director ends up working twenty hours a day. Because when he isn’t directing operations, every spare moment he’s sitting down and rewriting. So you’re constantly working. It was hard for me the first couple years; I was all movies. It was literally seven days a week—every waking hour, I was thinking about my movie.”

While his notes reveal thoughts, like “Change Death Star name … Luke doesn’t know father Jedi; Ben tells Luke about father,” a December 29, 1975, conversation with Alan Dean Foster, who was preparing to write the novelization of the film, reveals much more of Lucas’s mind-set as he wrote the fourth draft. Also in attendance were Charles Lippincott and John Dykstra, as the meeting was in the latter’s office.

Fairy tales: “I put this little thing on it: ‘A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, an incredible adventure took place.’ Basically it’s a fairy tale now. Star Wars is built on top of many things that came before. This film is a compilation of all those dreams, using them as history to create a new dream.”

The Kiber Crystal: “I think I’m taking the Kiber Crystal out. I thought it really detracted from Luke and Vader; it made them too much like supermen, and it’s hard to root for supermen.”

The Force: “I’m dealing with the Force a little more subtly now. It’s a force field that has a good side and a bad side, and every person has this force field around them; and when you die, your aura doesn’t die with you, it joins the rest of the life force. It’s a big idea—I could write a whole movie just about the Force of Others. Now it really comes down to that scene in the movie where Ben tries to get Luke to swordfight with the chrome baseball when he’s blindfolded. He has to trust his feelings rather than his senses and his logic—that’s essentially what the Force of Others comes down to.

“It’s also in the end now during the trench run where they have to shoot a torpedo into a little hole. They’re using this computer readout, and there are four runs on this thing: one guy makes his run and he fails; the second guy makes his run, and he fails; Luke makes his run, and he fails. When he comes around the last time, Vader is getting closer, destroying everything, Luke’s ship is damaged and he’s really in trouble—but at the last moment, he just pushes the computer aside. Ben, in the end, says, ‘Luke, trust your feelings.’ ”

Darth Vader: “Vader runs off in the end, shaking his fist: ‘I’ll get you yet!’ In a one-to-one fight Vader could probably destroy Luke.”

Luke’s father: “I’m going to have his father leave him his laser sword. I have to have a scene where Luke pulls out the laser sword and turns it on, to give audiences a sense of what laser swords are all about. Otherwise there is no way in the world to explain what happens in the cantina. It happens so quickly that unless you know that it’s a laser sword, you’ll be lost.”

Uncle Owen: “His uncle isn’t a son of a bitch anymore; because he gets killed, I have to make him sympathetic, so you’ll hate the Empire.”

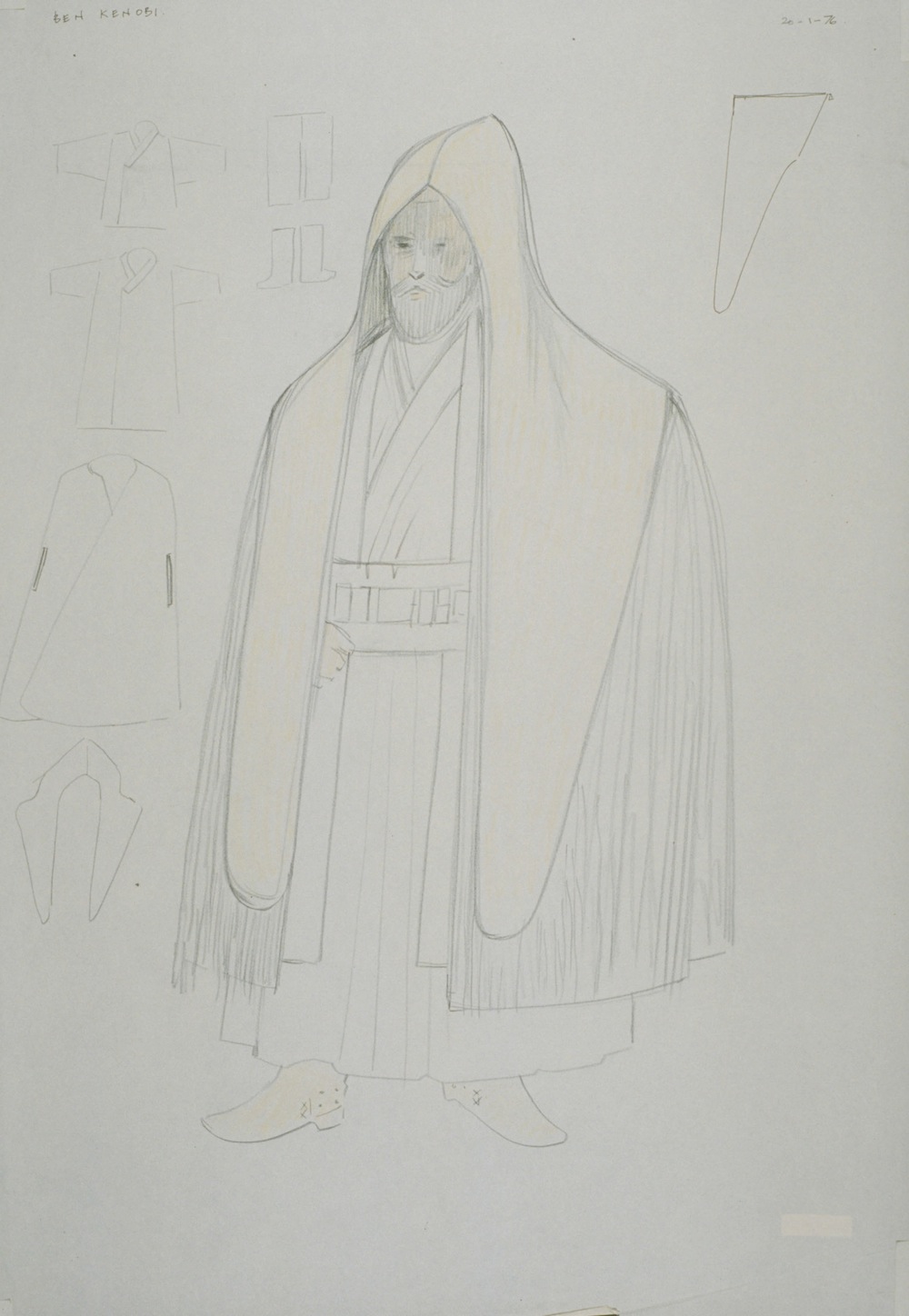

Ben Kenobi: “When this cranky old man pulls out his laser sword and cuts down three guys in a second—that’s when you realize the old man is a master. This guy is a lot more than you think he is.”

Tusken Raiders versus Luke: “I changed it because that electric windmill they put him on was a huge special effect that was going to cost an enormous amount of money. Now they just beat him up.”

Sequels: “I want to have Luke kiss the princess in the second book. The second book will be Gone with the Wind in Outer Space. She likes Luke, but Han is Clark Gable. Well, she may appear to get Luke, because in the end I want Han to leave. Han splits at the end of the second book and we learn who Darth Vader is … In the third book, I want the story to be just about the soap opera of the Skywalker family, which ends with the destruction of the Empire.

“Then someday I want to do the backstory of Kenobi as a young man—a story of the Jedi and how the Emperor eventually takes over and turns the whole thing from a Republic into an Empire, and tricks all the Jedi and kills them. The whole battle where Luke’s father gets killed. That would be impossible to do, but it’s great to dream about.”

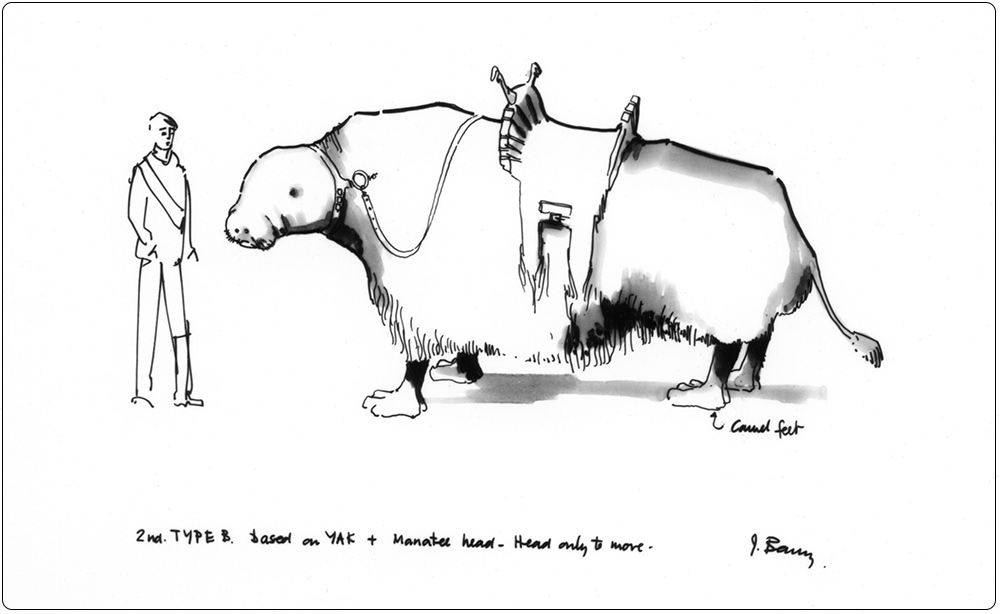

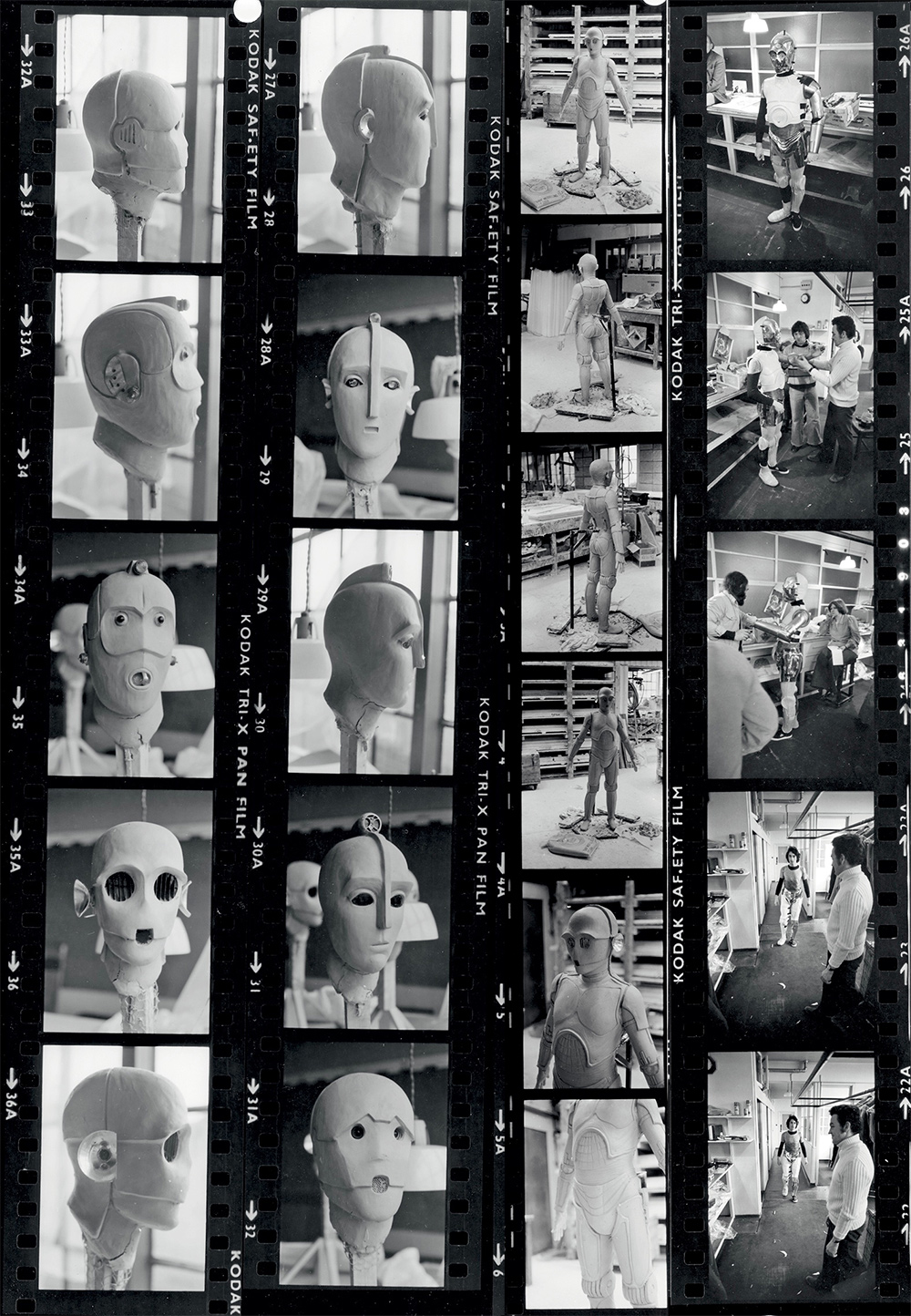

John Barry’s production sketch of a stormtrooper mount led to the creation of a giant practical model (below).

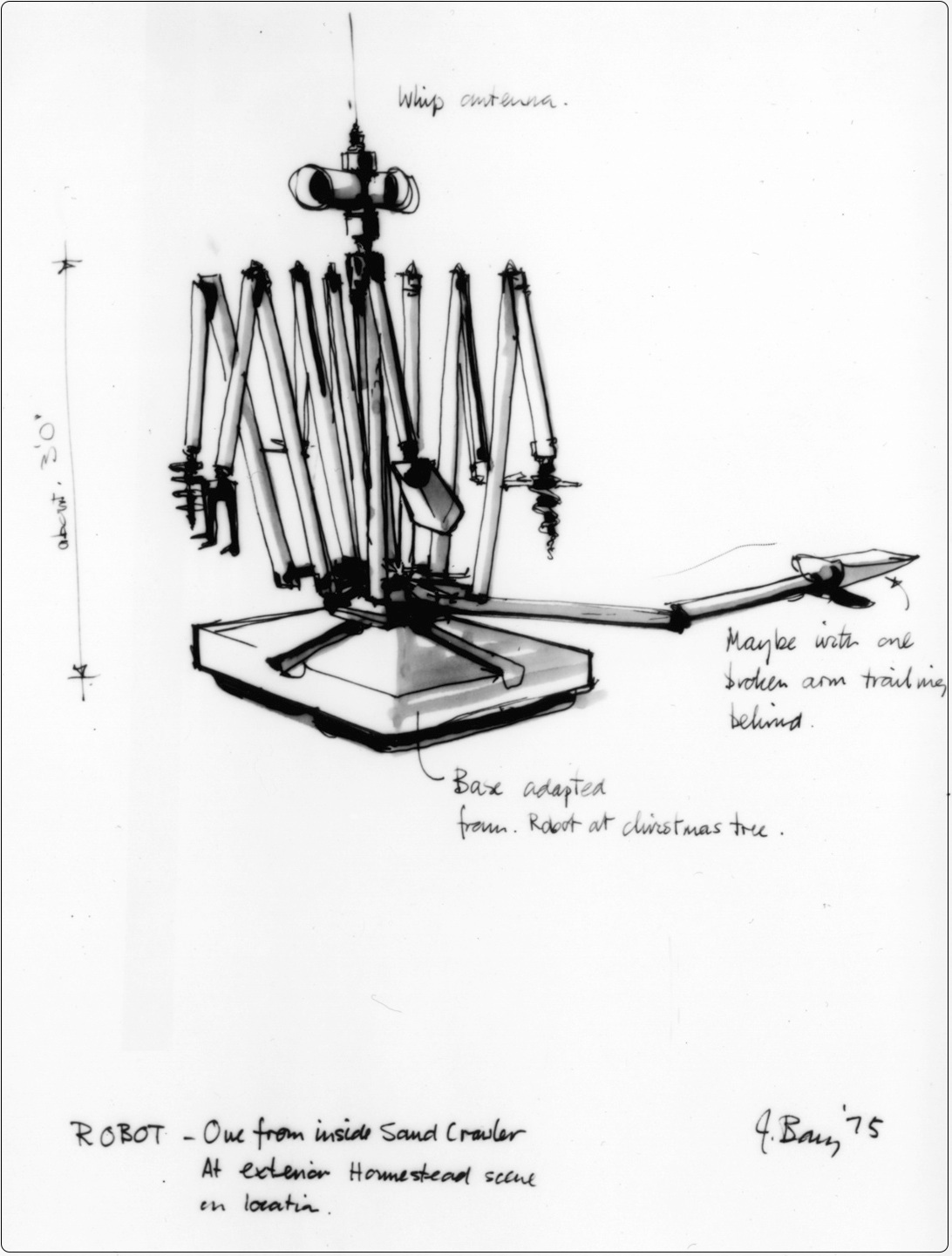

Three more John Barry sketches, all dated 1975: a robot destined for the homestead/sandcrawler scene.

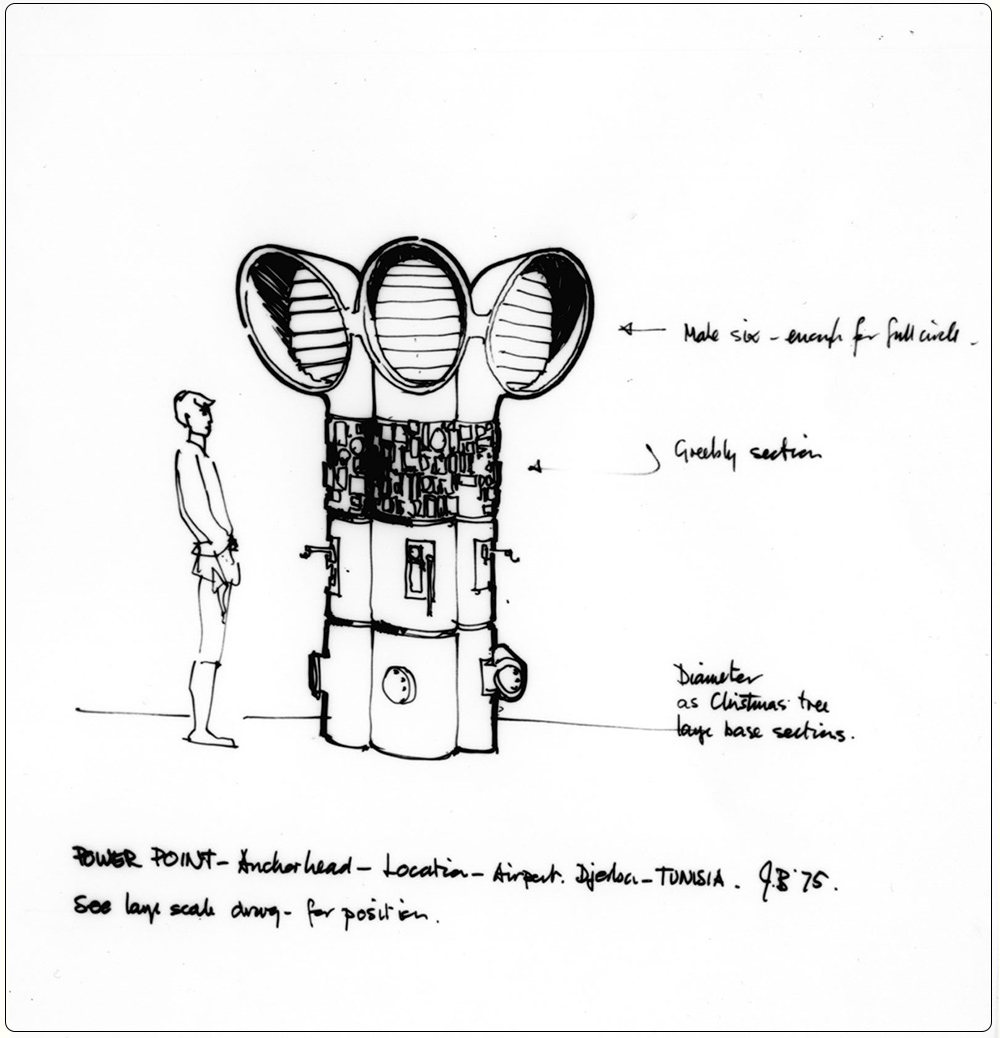

Another fixture designed for Anchorhead, at the airport location in Djerba, Tunisia, for the scene with Biggs and Luke

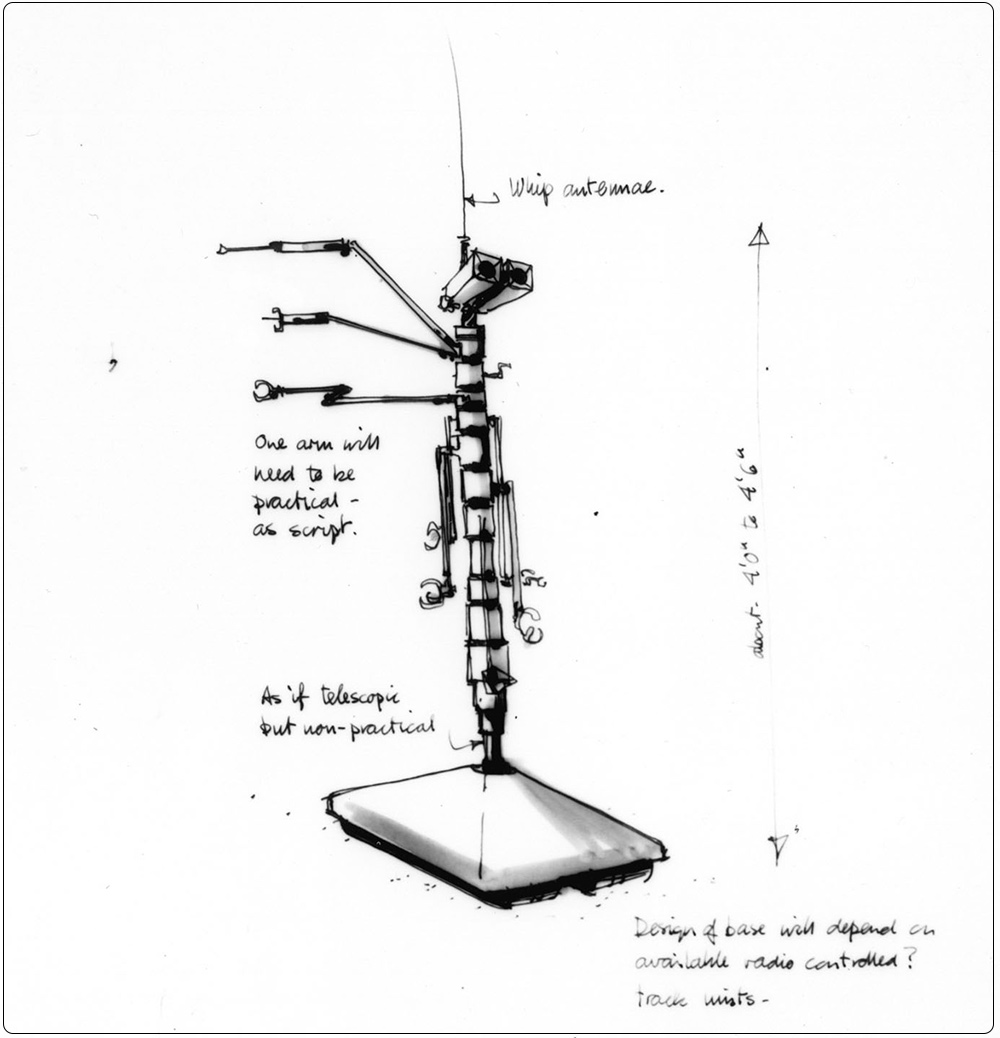

A robot for the scene in which Luke espies a battle in space; Barry specified in his notes that “one arm will need to be practical—as script.”

The “little thing” that Lucas added to introduce and establish his story’s genre was a direct result of his choice of reading between drafts. Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales was published officially in 1976, but copies must have made their way into bookstores earlier, because Lucas says, “I read Bettelheim, and it all began to inform the story and the characters.” Fairy-tale Princess Leia, for example, becomes much more prominent in the fourth draft, particularly in its beginning.

An area that seems to have given Lucas difficulty throughout the many drafts is the period of time between the cantina scene and the moment in which the pirate ship blasts out of Mos Eisley. In different contexts with a variety of foils, Solo’s character is searching for a way to define himself, and Lucas is never quite satisfied. In the fourth draft, still searching, Lucas has replaced Jabba the Hutt with Imperial bureaucrat Montross, whom Solo has to outfox in order to take off.

Lucas also further defines the character of Luke, altering his motivation. Whereas in the third draft Luke makes the decision to seek adventure himself, in the fourth his actions and reactions are more varied—he is less sure of himself.

“Usually, the hero has come to a decision on his own by observing and realizing the position he’s in and moving forward,” Lucas says. “This time the hero avoids that position. But then I have the position thrust upon him—because it’s inevitable. I’m taking the existential view and putting a slight determinist slant on it. I believe in a certain amount of determinism, from an ecological point of view. It’s that things essentially reach their own equilibrium. If you don’t live a certain way, ecologically speaking, you will be forced into a position that will level it. What I would call an ‘unpoetic state’ will eventually become a ‘poetic state,’ because an unpoetic state will not last. It can’t. It’s like economics. It’s like life, it’s like animals, it’s like everything. You can set up an artificial reality, but eventually it will equalize itself, and become real.

“When the challenge comes with Ben at his home after he gets Leia’s message, Luke immediately rejects it,” Lucas explains. “He wants to go fight the Empire, you can tell that he wants to, but he doesn’t feel that he can take on the responsibility. As a result, destiny comes into play. Because if you don’t do anything about the Empire, the Empire will eventually crush you. There is a scene where his friend Biggs explains that you can’t avoid the issue forever. Eventually it will catch up with you, and then you will suffer the consequences.

“To not make a decision is a decision. It happens in all countries when a certain force, which everybody thinks is wrong, begins to take over and nobody decides to stand up against it, or the people who stand up against it can’t rally enough support. What usually happens is a small minority stands up against it, and the major portion are a lot of indifferent people who aren’t doing anything one way or the other. And by not accepting the responsibility, those people eventually have to confront the issue in a more painful way, which is essentially what happened in the United States with the Vietnam War.”

Lucas and Barry study a set maquette.

In early January 1976, armed with the fourth draft and a go-project, Lucas arrived in England, joining a production house now advancing at full throttle. He settled into a house in the Hampstead area, and the business of preparing The Star Wars for location shooting in Tunisia in late March began in earnest. The small production offices at EMI were now fully staffed: “There’s Gary Kurtz, the producer, his assistant, Bunny,” Robert Watts says, mentally running down the corridor. “Then there’s me and Pat Carr in the production office, with Bruce Sharman, who’s the production manager. Go to the accounts department, you’ll find Brian Gibbs, the production accountant; he has three assistants and a secretary, and then there’s Ralph Leo, the Fox auditor who’s with us, and Graham Henderson, who is in charge of controlling set costs. Andrew Mitchell is the managing director of EMI.”

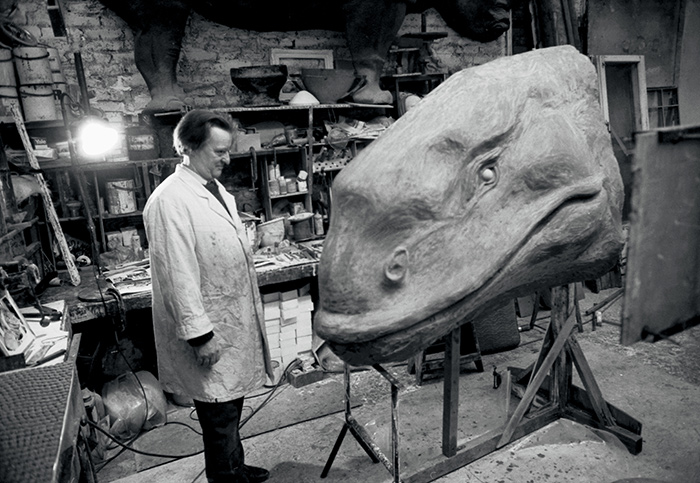

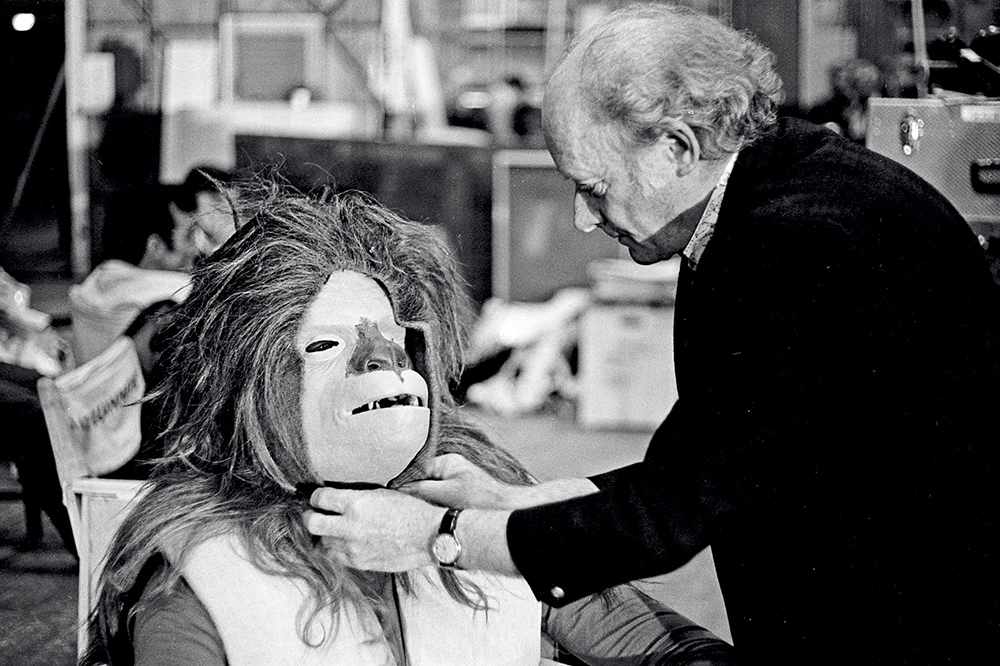

Two new department heads had also moved in: costume designer John Mollo and makeup artist Stuart Freeborn, both of whom had actually been hired the previous month, but whose work really started in the new year. “I had been working on another Twentieth Century film, The Omen,” Freeborn says, “and we were making some false dogs for the close-ups; otherwise we’d have some bitten artists. George Lucas popped in to see what we were doing, and it all happened from there. He said, ‘If you can make these dogs that all work, then have a go at making the animals for this picture.’ ”

Stuart Freeborn had started his career working with the late Sir Alexander Korda in 1936. He labored under contract with various companies until 1947, and then went freelance, enlisting the aid of his wife, Kay, and son, Graham. “They’re usually with me because they know the routine, and they’re both very good at certain things.”

“I knew of Stuart from 2001,” Lucas says. “He was the guy I wanted, because I really liked the apes in that film. It was a fantastic job.”

On The Star Wars, Freeborn was faced with a multitude of creatures instead of just one. “Once we got the prototype on 2001, they were all designed on the same principle,” he says. “For this film, of course, every one’s different; each one’s got his own problem—every one of them is a prototype.”

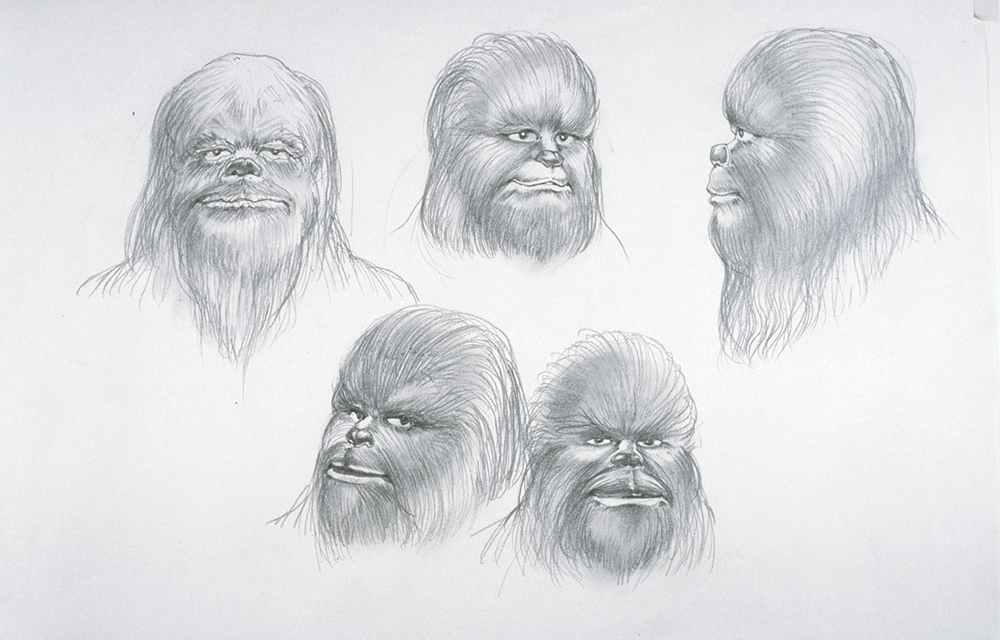

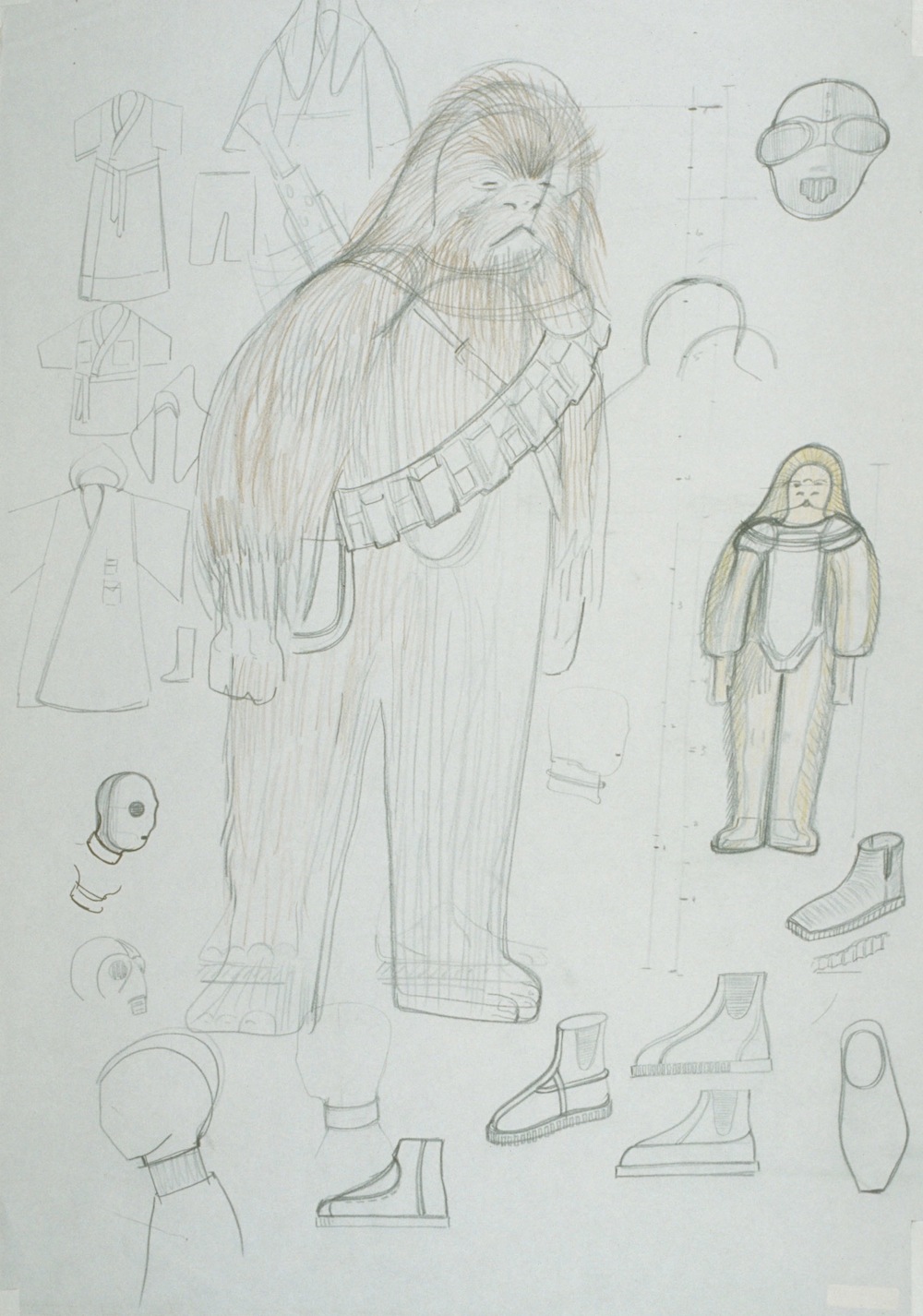

For his first three or four weeks, Freeborn worked alone on the movie’s most important prototype, Chewbacca, creating concepts and masks based on McQuarrie’s design. He was joined by his family and assistants as the load increased week by week.

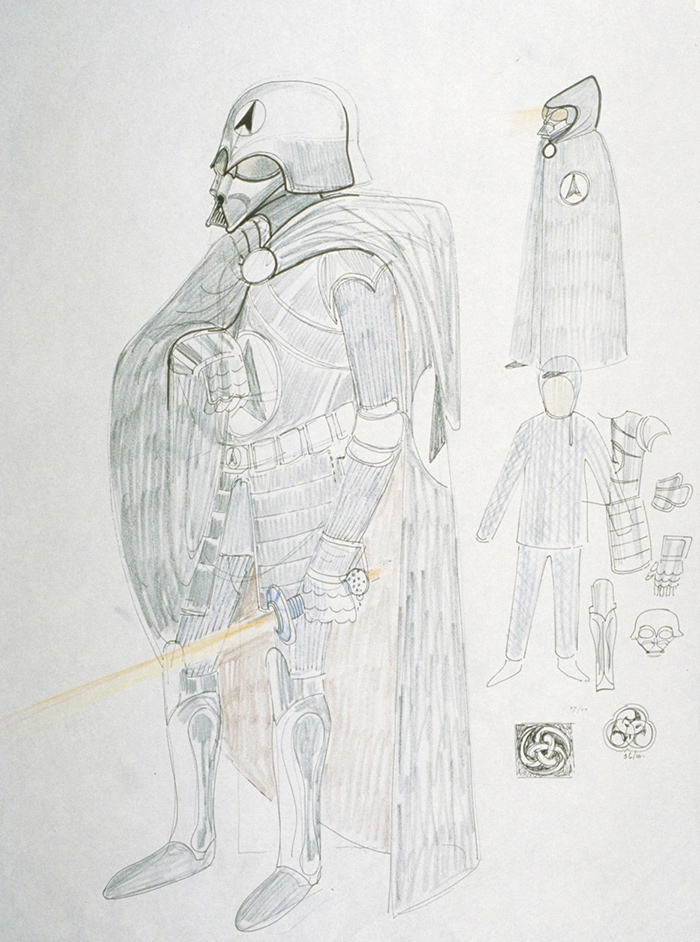

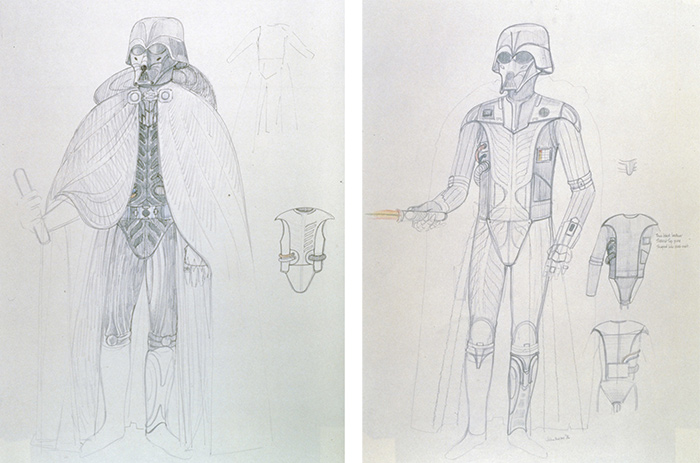

The route to John Mollo was slightly more circuitous. “We were in talks with Milena Canonero, who had worked on Barry Lyndon [1975] and A Clockwork Orange,” Lucas says. “But she was about to do a documentary on Fellini, so she recommended her assistant on Barry Lyndon, John Mollo. I met him and he seemed very good. I wanted somebody that really knew armor, somebody who was more into military hardware, rather than somebody who knew how to design for the stage. I wanted designs that wouldn’t stand out, which would blend in and look like they belonged there.”

In Mollo, who had written with his brother Andrew several books on military fashion, Lucas found a good match. For The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), Mollo had supervised the creation of three thousand military costumes, and he had worked on Napoleon in a similar capacity.

John Mollo

“Milena Canonero rang me up and asked if I was doing anything for the next six months,” Mollo says. “And that’s how it happened, really. The first few days that I was working, they weren’t quite sure if the film was coming off, so I sat around reading the scripts and looking at the deal with a certain amount of horror. Immediately after Christmas, Ron Beck joined and we started setting up a fashion showing for George.

“We got hold of an acting model and a Polaroid camera, and we went along to the costumers where we tried to find items in stock that approximated the drawings. For Darth Vader, we put on a black motorcycle suit, a Nazi helmet, a gas mask, and a monk’s cloak we found in the Middle Ages department. We got things from every department and put them all together, and then we Polaroided them. When George came back to England in January, we repeated the performance at Berman’s; it was a live fashion show. George would say, ‘I don’t like that; I do like this.’ We did very little drawing; it was more of a practical make-do amend, because there was already an established style.”

The style had been meticulously worked out by Lucas and McQuarrie, who had dedicated himself to that task from July 24 to August 29 of the year before. “Ralph and I have already drawn out many of the designs, so it’s often a matter of pulling it together,” Lucas says. “For the stormtroopers and Darth Vader, Ralph had a very strong influence. Essentially they are his designs. The other characters, such as the princess, Mollo actually did.”

Mollo also used paper dolls to try out ideas and, together with Lucas, consulted many reference books in his office at Elstree, often checking with Barry to see how the costumes would fit into the sets. “We’re quite close together,” John Barry says. “John is just down the corridor, so we see each other often and he looks at what I’m doing and I look at what he’s doing, and we talk about it all the time.”

The need for instantaneous communication among all the department heads and Lucas was all the more necessary given their now incredibly accelerated schedule—and as expected, costs began to soar, particularly those related to the building of the sets. “We were very, very stretched at that point. Normally, this sort of picture you’d expect to prepare for twenty-six weeks, or sixteen certainly,” Barry adds. “But because it’s twelve weeks, it really is frighteningly busy. It really is quite a nightmare.”

“We could have had a reasonable number of people working at reasonable hours,” Lucas says. “But because Fox waited until the last minute, we had to hire twice as many people and we had to have them working on golden time, twenty-four hours a day, in order to get the sets finished—and that cost us a lot more than it normally would have cost us. The creatures were a big problem, too, because they wouldn’t let us start the makeup people. They were six weeks short. Everybody was six weeks short, so, to get all their work done on time, they just cut six weeks off the schedule. It was therefore impossible for everybody, and there was a lot that never got finished. The monsters were part of it, the sets were part of it, the special effects were part of it, transportation costs were part of it—the ramifications go all the way through the picture.”

“That’s why we’ve burned the midnight oil for a long while now,” John Stears says.

“The overriding thing for me really at that stage was the amount of work that we had to do and the amount of stuff there was to achieve,” says art director Norman Reynolds. “We had grave doubts about getting it done in time.”

“The most amazing thing about it all is that it’s down to Bill Walsh, the construction manager, who is making an enormous contribution to the movie,” Barry notes.

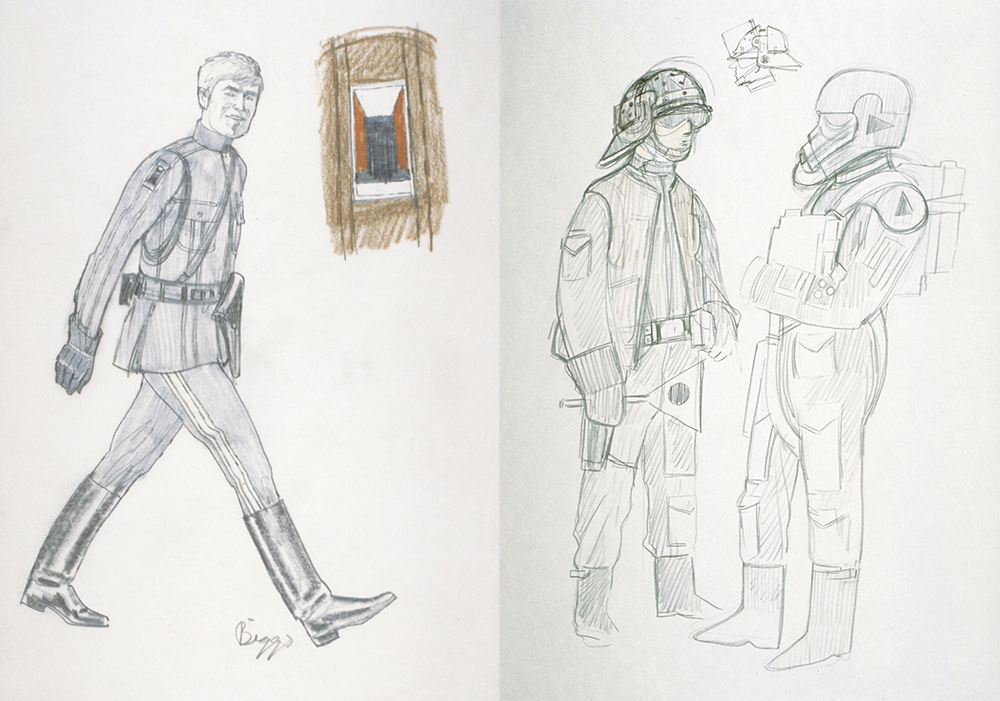

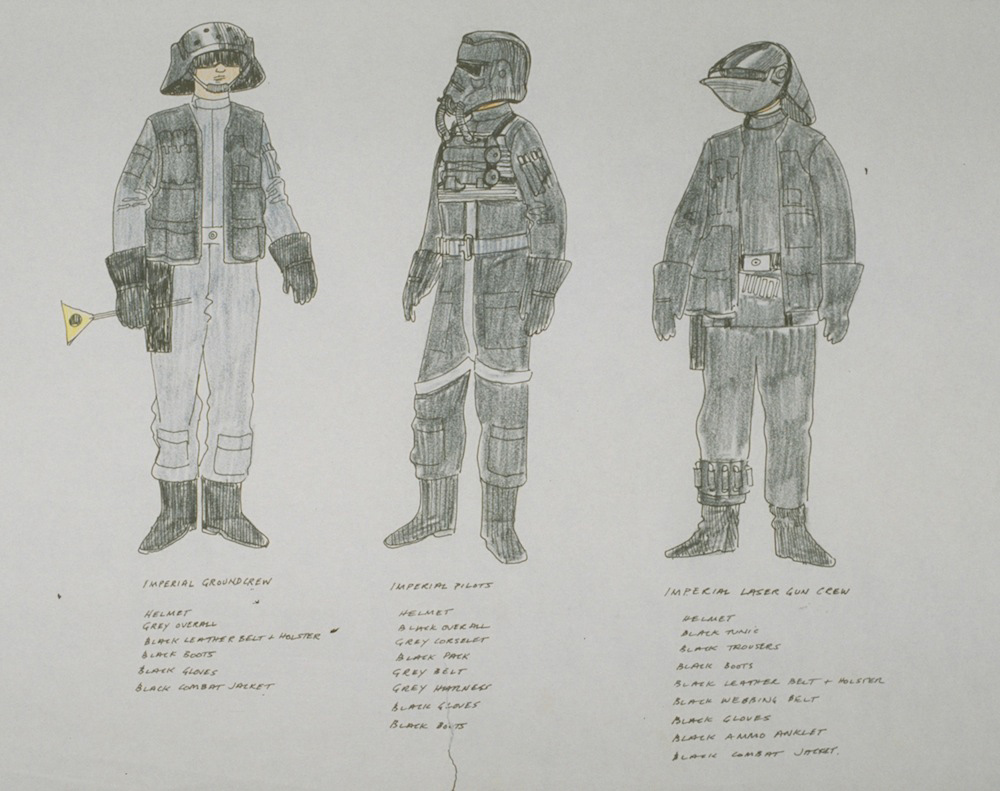

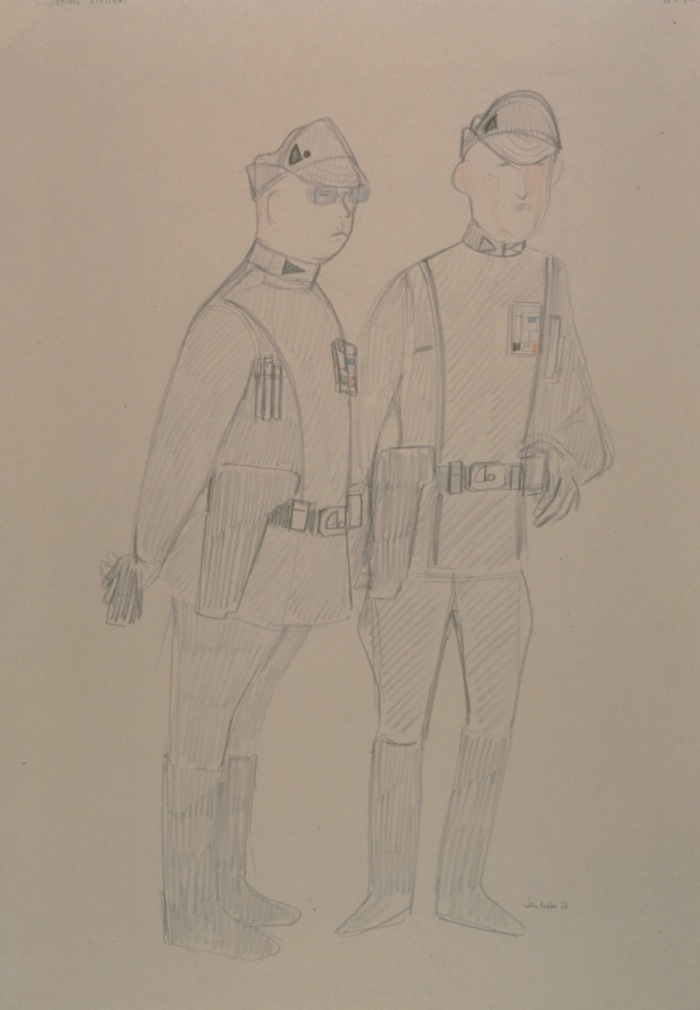

John Mollo’s military costume expertise, inherent in his designs, was one of the reasons Lucas hired him.

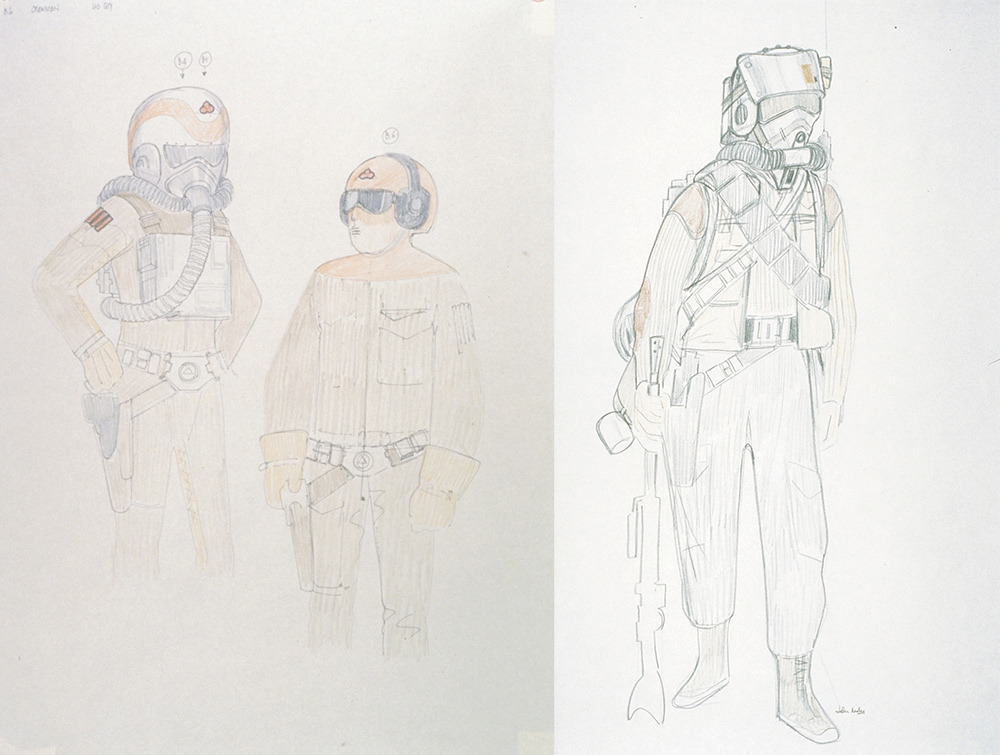

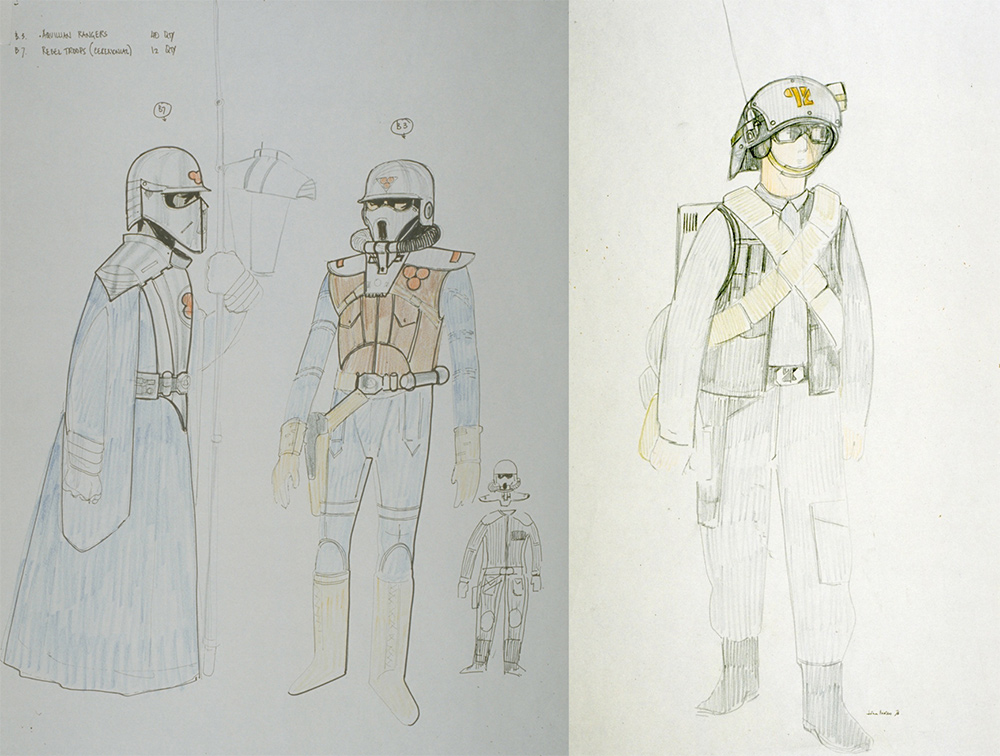

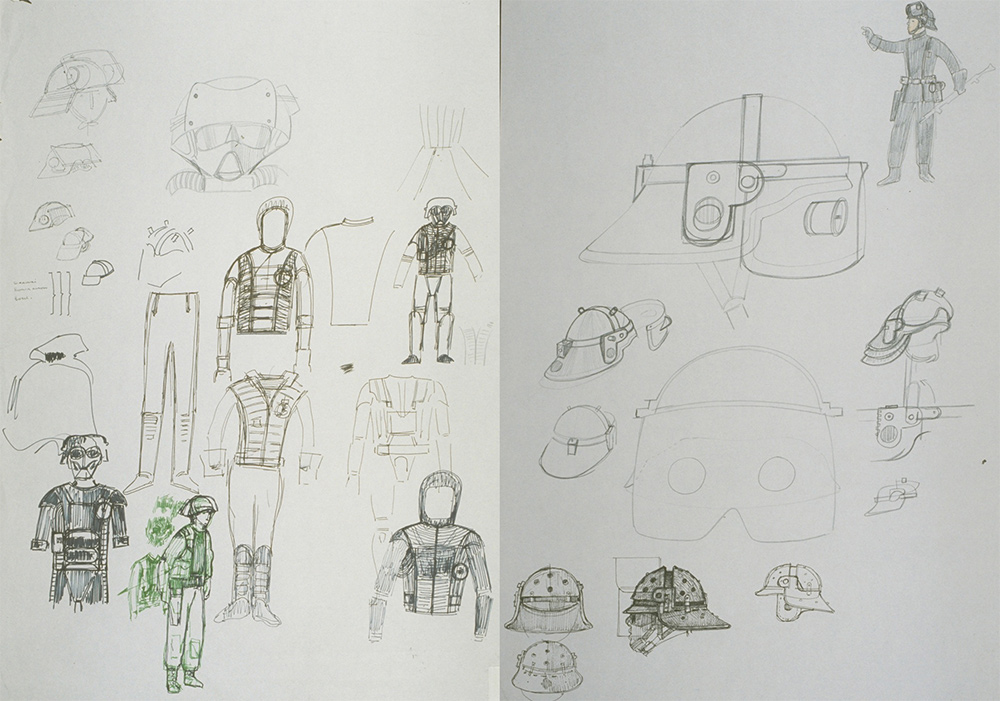

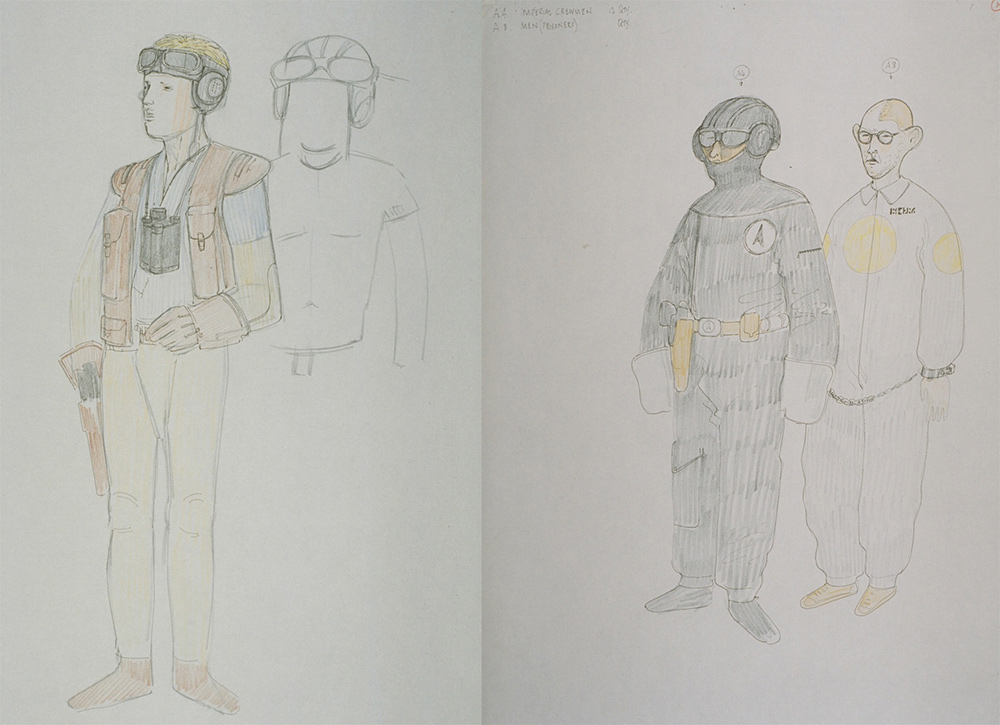

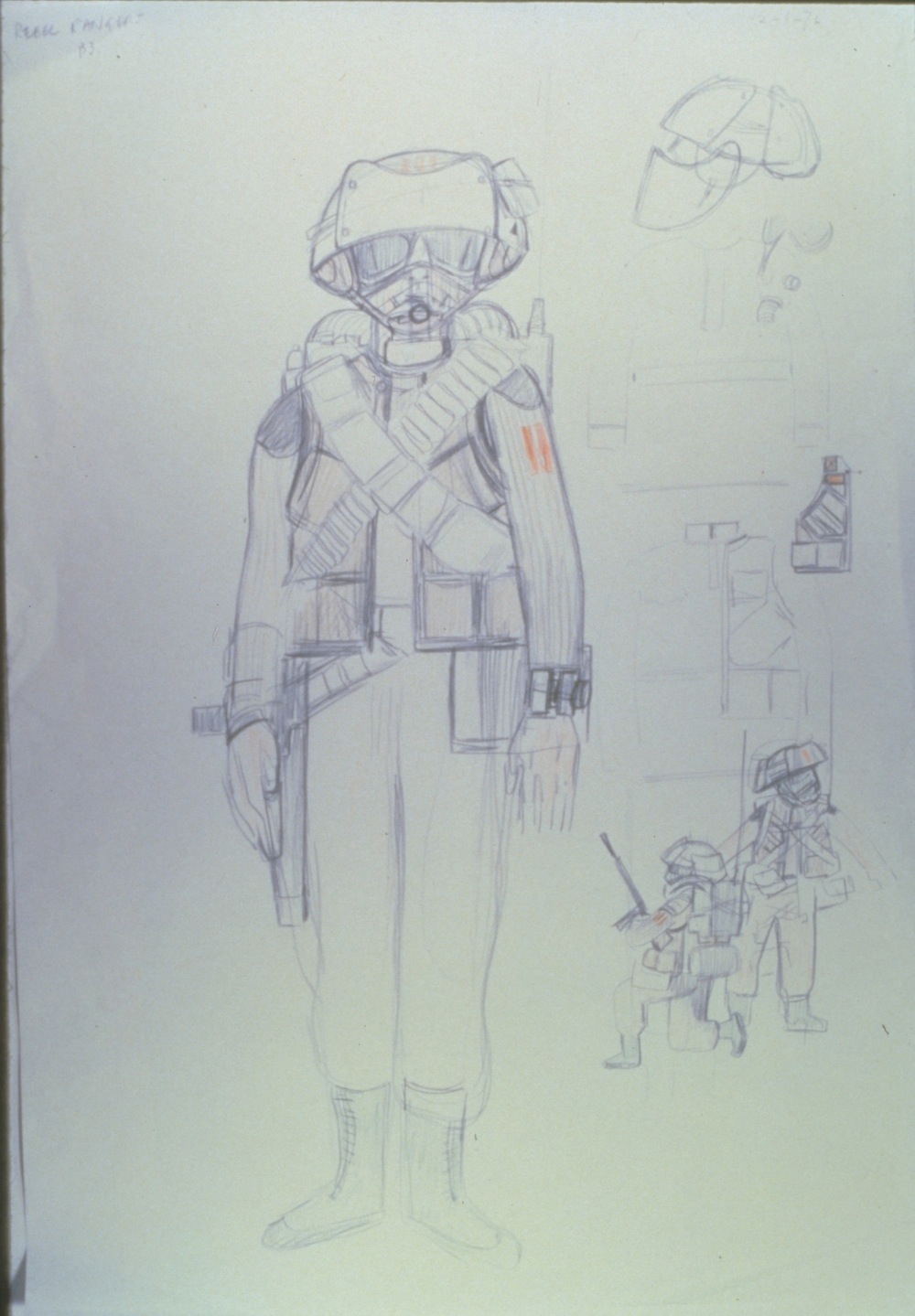

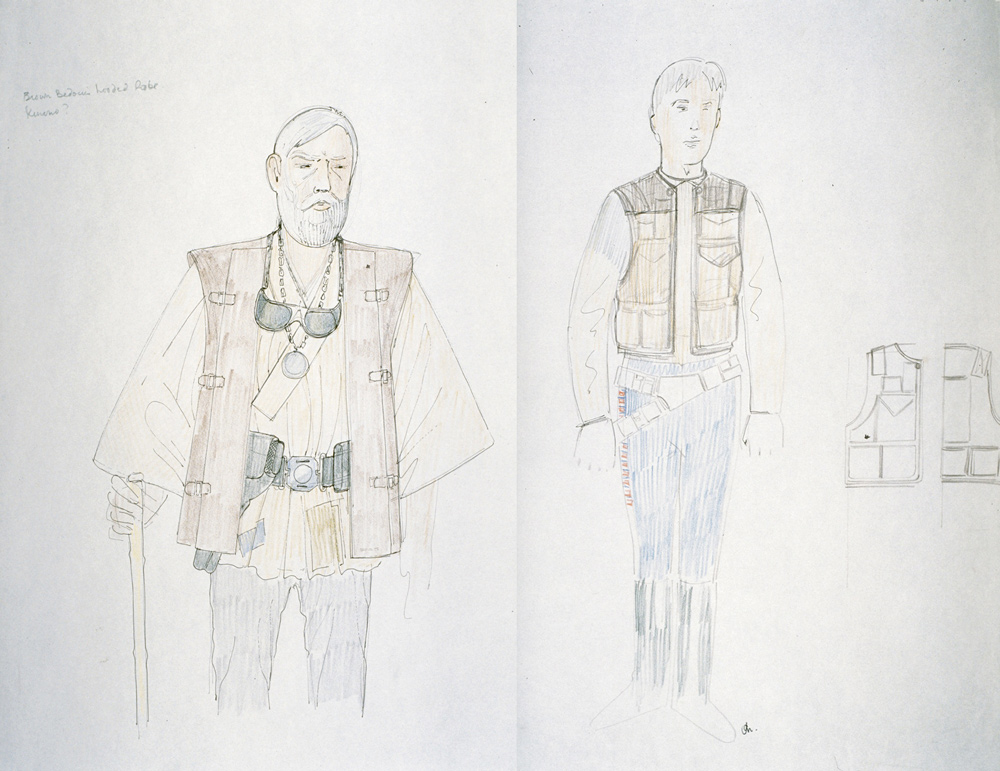

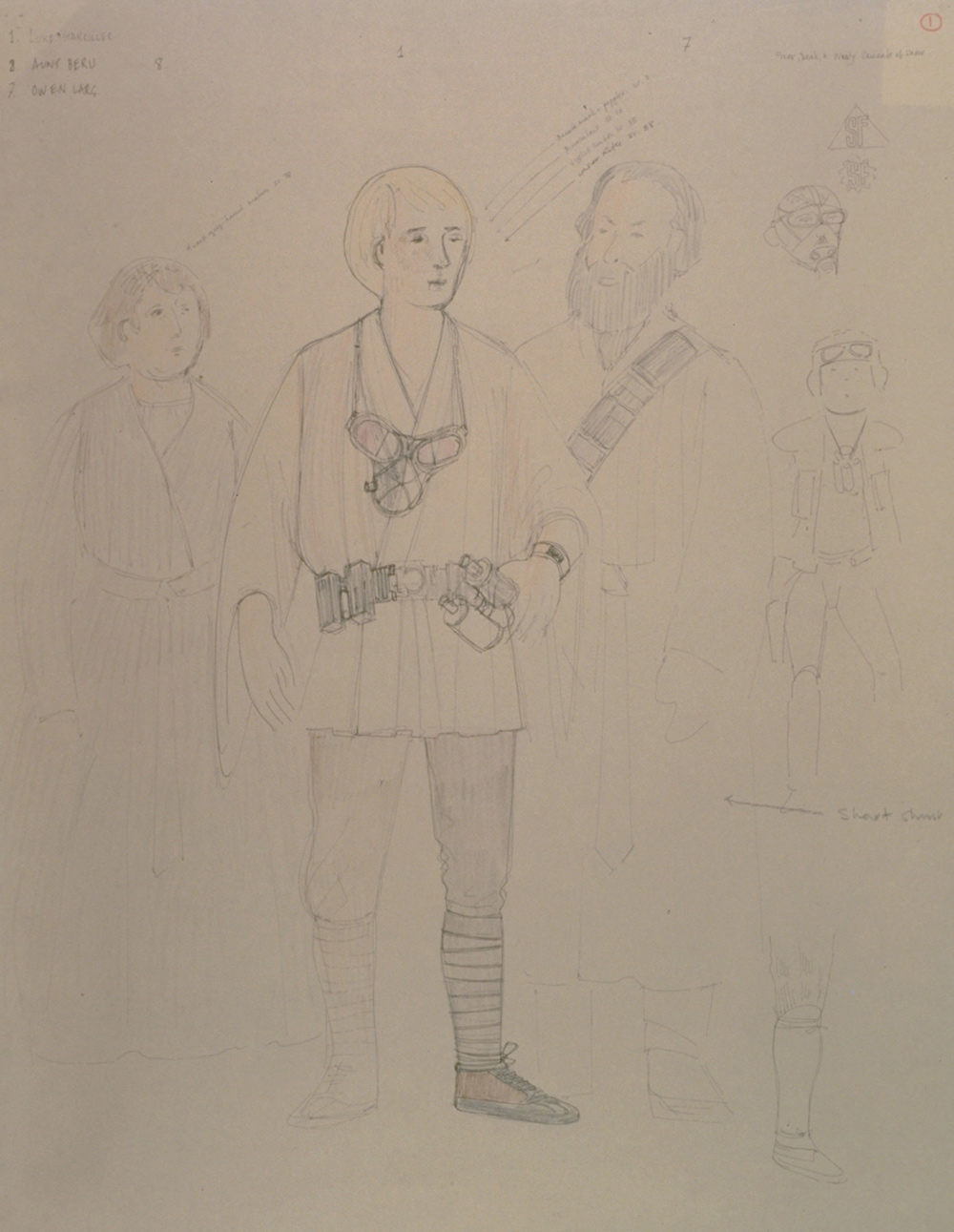

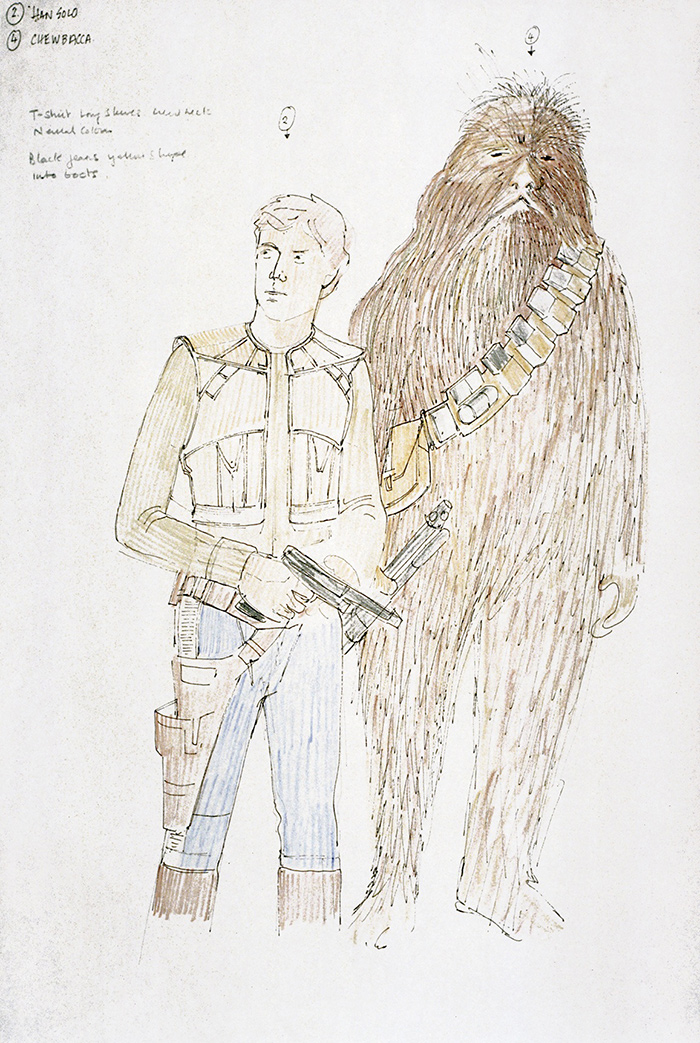

Costume concept sketches by John Mollo.

Lucas would often pop in to see how Stuart Freeborn was doing on his first project, Chewbacca the Wookiee, which he was making from straight yak hair. “I would go in there every day and push the nose around a little bit and push the chin up,” Lucas says. “I kept pulling the nose out and pushing it back. It was difficult, because we were trying to do a combination of a monkey, a dog, and a cat. I really wanted it to be cat-like more than anything else, but we were trying to conform to that combination.” “Chewbacca was a fascinating one,” Freeborn says, “because he had to look nice, though he could be very ferocious when he wanted to be. It was fun making a monster that looked friendly and nice for a change, instead of being menacing. I had seen a sketch [by Ralph McQuarrie] and I based it on that because it was very good, and it looked just right to me.”

Freeborn’s sketches, which bear some resemblance to the man.

Creature makeup supervisor Stuart Freeborn at work, along with his wife, Kay, at Elstree.

(No audio)

(1:16)

To rally and coordinate his troops, Lucas held Friday production meetings. To communicate his visual dictates, he had McQuarrie’s and Johnston’s paintings and drawings, and his World War II footage, but he occasionally screened films to make a point. “George knows what he wants on the screen,” Watts says. “I think it first became apparent to me when, about three months before we started shooting, George ran pictures, usually on Wednesday evenings, including Forbidden Planet [1956], Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West [1968], and Fellini’s Satyricon [1969]. Tunisia was like the landscape of the Leone film, which was indicative of the feel George wanted to inject into the space age. My own personal feeling about George is that he is an instinctive director; he is communicating through film.”

Lucas was also studying how his potential cast communicated through film, reviewing their tests. “You get a completely different impression when they are actually photographed,” he says. “How the film reacts to them can be altogether different, too. Sometimes I’m surprised in various ways. Somebody would be really terrific in person, but when you finally get them down on film, they don’t work at all; or somebody else might be nondescript in person, but when they get on film, they photograph completely differently—they come alive. It’s even quite different going from videotape to film. Some people who work on videotape, don’t work on film.”

One actor who did not need to be tested for his chemical relationship to film was Anthony Daniels, who had already been cast as the person inside the robot C-3PO, signing his contract on December 5, 1975. “When I went back for the second interview, Pat Carr, the production secretary, asked when could I go to the studios to be cast,” Daniels says. “She meant ‘cast in plaster,’ so I said I hadn’t been cast in the part yet. She seemed slightly embarrassed and so did Robert Watts. I thought that was a bit strange. But I went in and talked to George again for about an hour, and I asked him, ‘Can’t I play it, because I’d really like to.’ And he said yes. It was just a gas. It was like winning a prize. But I later found out that Lucas had cast me the first time—and my agent hadn’t wanted to tell me about it in case I hated the whole idea! So I was excited about the whole thing and started going to the studios to have the costume made.”

Following the green light, in early January, negotiations were also concluded with Alec Guinness, who agreed to play the part of Ben Kenobi for £15,000 per week and 2 percent of the film’s net profits. “I suddenly thought that I’d like to make two or three more films,” Guinness told The Sunday Times. “I feel there’s a new kind of filmmaker about. The days of the big cigar are over. They live more simply. I find them easier to work with.”

“I can see how the story would have appealed to Guinness,” Harrison Ford says. “It’s a real American story and it has a mythological quality to it; for him it probably has the cowboy-and-Indian concept of America. I think that Guinness thought this was a picture about America.”

With Guinness cast, the other roles would have to work around him, as an ensemble. Though nothing else was definite, Christopher Walken was an option for Han Solo, with Charley Martin Smith a Luke Starkiller possibility, along with Will Seltzer and Mark Hamill, who was still in the running despite his own misgivings. “I think if George had chosen Walken, the princess would have been Jodie Foster,” Ford says. However, Foster wasn’t yet eighteen years old, which was also true for Terri Nunn. Their status as minors would’ve been a big drawback to the compressed schedule, as they could have worked only a limited number of hours per day.

On January 10 George Lucas debriefed Gary Kurtz on the changes to the film represented by the fourth draft. During their conversation, Lucas mentions new scenes or reworkings of scenes that never made it to the film or any of the drafts, while Kurtz’s preoccupations are largely logistical.

George Lucas:…We go back to the planet Tatooine and we have Luke and his friends, and he sees Biggs and they go outside. We cut back to a confrontation between Vader and the princess, then we cut back to Luke and Biggs at the Anchorhead power station. The scene is now inside, but we’ll probably move it to the outside, or half and half.

Gary Kurtz: The discussion is now later in the film?

Lucas: Yeah. Then Artoo and Threepio are wandering around in the desert. They have an argument, and they split up. Then we go to the power station; we have Luke and Han Solo in that scene, which is the one that may be changed … Luke is going to have a scene where he works with the robots to find out where they’re going; all that is a little bit different. He says he’ll help them; he’ll take them to Ben Kenobi, but that’s the only place he’s going to take them.

Kurtz: They don’t think they could make it on their own?

Lucas: Well, they’re not having very much success; they’d probably get picked up by Jawas again, so he takes them.

Kurtz: In the crossing-the-desert process [front projection] scene, they’re watched by the Tusken Raiders; they make camp and they’re attacked by the Raiders?

Lucas: Right. Now, in this attack they don’t put him up on the windmill, they just drag him into the clearing and start looting the car; then Ben comes and scares them off. Then Ben takes Luke back to his house, and Luke and Ben get into various discussions about the robots, they see the message, and Ben talks Luke into taking him to Mos Eisley [. . .] So they go, they see Mos Eisley, and they drive through and ask some Jawas for directions, and…

Kurtz: You’re eliminating the crystal chamber scene, where Darth Vader talks to the Sith knights?

Lucas: The crystal chamber is cut. It might be replaced by another scene with Vader. I’m not sure. I know the crystal chamber part is out, but there might be a scene with Darth Vader in the prison with Leia and a torture robot.

Kurtz: I’m just worried about which scenes are shot with which actors…

Lucas: Well, I may be moving this scene earlier.

Kurtz: Let’s see, they go into Mos Eisley…

Lucas: Right. In the cantina, they have the fight with the rodents, and they meet Chewbacca and Han Solo, who’s sitting at one of the tables. Now, here is the tricky part: After the cantina scene, we’ve faded out or dissolved or cut, and it’s morning. We cut to Luke or Han—doesn’t make any difference because they’re going to be intercut later—say we cut to

Luke first. Luke and a man walking down the alley. Cut to them outside of a speeder lot selling the speeder—

Kurtz: Seen from across the street.

Lucas: —seen from across the street in a long shot. Intercut with that is Han and Chewbacca getting the spaceship ready in the docking bay. And some Imperial troops come in. They want to search the ship … I think I’ll switch that. Luke and the group arrive at the spaceship. They all get on board and Han starts making ready for the trip, then the Imperial troops arrive. They get into a gunfight with the troops. Really Han does, nobody else does, and they take off just in the nick of time.

Kurtz: It’s going to be harder to make that alley scene and the used-speeder dealer work during the daytime than it is at dusk.

George: Well, I can do it in early morning.

Kurtz: Okay, so they sound the alarm. Then we cut inside the pirate ship?

Lucas: Right. Then we go into a kind of warp drive, and they go faster than the speed of light, and there is that scene where they are playing the game and Luke is learning the Force—

Kurtz: Now is that going to be during the time warp?

Lucas: Yes […] And they get drawn in to the Death Star. Then you intercut that with Darth Vader finding out that they’ve arrived, that they’re there, they’ve caught ’em.

Kurtz: He knows at that time that they’re the right ones?

Lucas: Yes. Cut and the troops board the pirate ship in the docking bay, except no one’s aboard. So they go out to get some scanners. Cut and it’s empty. Bottom panels get kicked out of the floorboards, and our group emerges. They start trying to figure a way of taking off and go into the main living area of the spaceship—and Darth Vader’s there. But Ben has mysteriously disappeared. Instantly, in cutting, all of a sudden he’s not in the group anymore. Darth Vader says, ‘Nice try,’ and he marches them off the ship, which is the first time you realize that Ben isn’t there anymore. Darth Vader puts them down in a cell. Everybody goes in the cell except Artoo, and they start taking Artoo down the hallway—except when they get down to the end of the hallway, Ben attacks the troops. I haven’t quite figured out if Vader’s still there … No, Vader won’t be with this group. The troops march little Artoo down the hallway—and get wiped out by Ben in a very slick way. Then you cut into the prison cell, and all the guys are there, and Ben opens the door and they all escape. They run down the hallway and go into the princess’s cell.

Kurtz: How does Ben find out that she’s there?

Lucas: He has a way of knowing these things, because he has the Force of Others. It might get mentioned earlier. Maybe he just senses her presence. Afterward, they all go down into the underground dungeon and fight with the Dia Noga. The robots are now in that sequence.

Kurtz: Artoo goes along under the water…

Lucas:… with the light on, the little periscope—

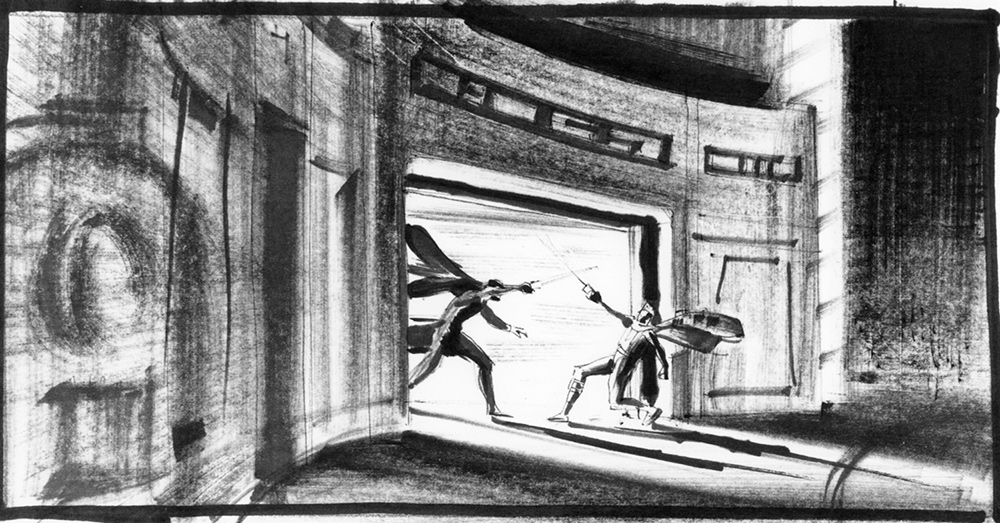

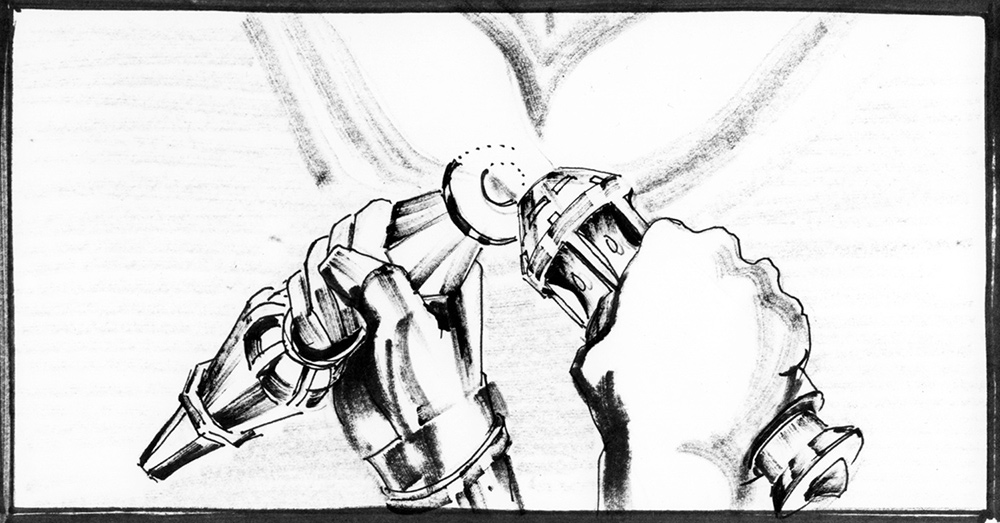

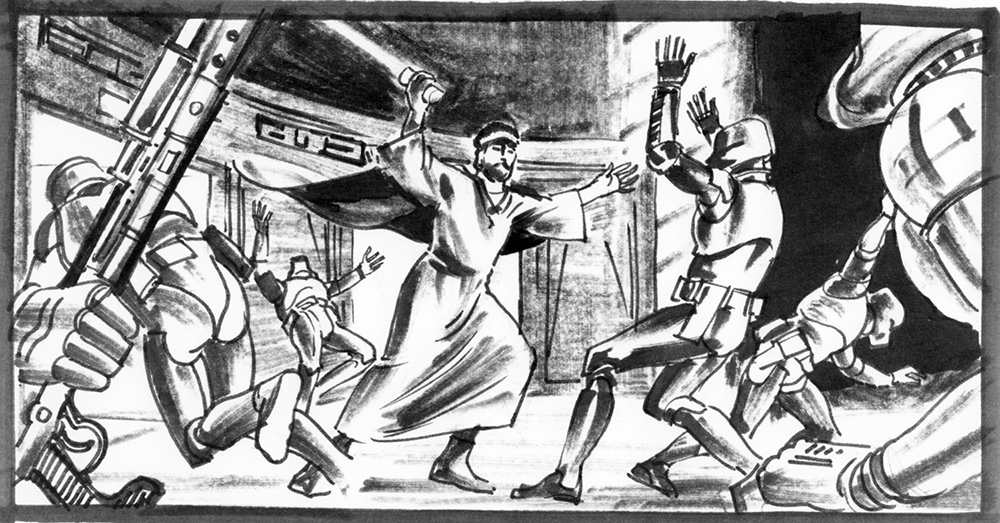

In England, Ivor Beddoes took over storyboarding for principal photography, while Joe Johnston continued in the States doing them for the VFX, concentrating on Ben Kenobi battling Darth Vader and a group of storm-troopers.

Lucas: The little antenna, something that pokes out of the water. We’ll have a skin diver play that part.

Kurtz: Let’s back up. When they get put in the cell, what are they wearing?

Lucas: Just their regular clothes.

Kurtz: They don’t get changed into prison garb or anything?

Lucas: No. I thought about that. I decided we won’t do it. They don’t stay in there long enough.

Kurtz: So Ben shows up and helps them escape, but there’s no big fight in the control room of the prison?

Lucas: No. Except for the fight with Ben.

Kurtz: Do we see how Ben gets in there?

Lucas: No, we don’t see how he gets in.

Kurtz: So they get out of the garbage room and they’re across from the starship…

Lucas:… and they see the starship. This is all very complex. It’s going to have to be worked out in detail; I don’t know whether I can just sit here and tell it. Ben will split off because Vader will have shown up in one of the hallways, and they will have this confrontation just like they did before. Before they fought over the Kiber Crystal, but now the Kiber Crystal’s gone.

Kurtz: What about Ben being wounded, and all that stuff aboard the pirate ship after the end of the fight?

Lucas: Ben is going to be wounded, but not as bad, so there’s no big scene afterward. [At one point Kenobi was budgeted for a hospital “smock.”]

Kurtz: All right, so you have an exterior shot and the pirate starship arrives and you see the fourth moon of Yavin, and the two lifepods jettison away. This is all in miniature…

Lucas: No, you don’t see the lifepods jettison away. You’re in orbit, and she says, ‘The Death Star is behind us, so nothing’s going to be here too long.’ They’re in orbit, and you just cut down to the jungle. You have these shots across the steaming jungle. You cut to the shot of the temple, that one in the drawing, and the troops run out and greet them. They’re in a little car and come riding up…

Kurtz: A couple of long shots…

Lucas: Yeah, it moves right along. You cut inside—

Kurtz: Now, the discussion of where the vulnerable part of the Death Star is—that’s in a little side room, in one of the war rooms?

Lucas: In that briefing room, which is connected to the war room; it’s all one big room. Half of it is briefing room and half of it is war room.

Kurtz: So then they have the big fight, then Luke comes back and lands, and we have the scene where everybody runs up and greets him, and then we go to the throne room scene. That happens the same way as before.

Lucas: Yes. Two points: the Crystal Chamber is now out, and the docking bay control room is now out. I’ve got to tell John Dykstra about that.

Kurtz: Before Vader and the TIE ships take off, is there anything of them in preparation?

George: Yeah. He can be in a hallway. I think I’m going to have a big control room on the Death Star, because I want to try to develop something where they’re approaching the green fourth moon. Truth of the matter, I have much more script than I need…

Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz discuss the story as the former nears completion of

a shooting script. (Recorded on January 20, 1976)

(1:39)

The main work at EMI was always building the sets, and Lucas and Barry recommenced their intense consultations that had been interrupted by Fox’s six-week delay. “For three or four weeks George and I were both sitting on the same stool in front of the drawing board,” Barry says. “George has quite a good grasp of it all; he’s a mechanically minded person and he understands the blueprints. The most important thing about a set is how it works: What can you see from the doorway? So we talked about that for quite some time, both of us drawing at the same time, and George saying, ‘I don’t need that. I will need that corridor.’ It’s up to the art department to try and find out what it is he wants, and then make suggestions which he’ll accept or otherwise, but he has an idea in his mind about all these things.”

“Barry brought a lot of knowledge about building sets,” Lucas says. “How you maneuver things around, use forced perspective, or build a false wall. He did a lot of the set designs, because I had never worked on a set before. I learned a lot from John.”

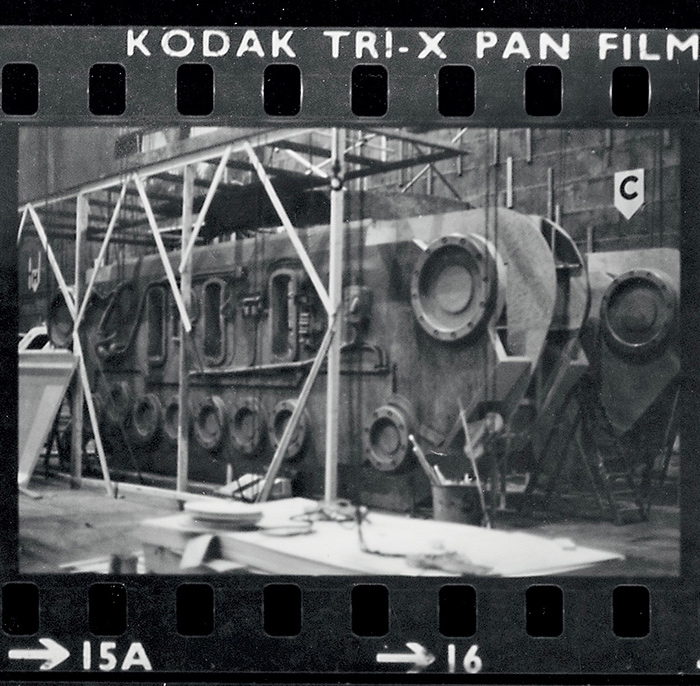

One of the ongoing challenges was coordinating production in England with the special effects in Van Nuys. “They sent me very good photographs of the model—the exterior of the pirate starship—as they were building it,” Barry says. “At that time we were building our exterior, too. With the X- and the Y-fighters, they just made two extra models when they cast them. Now the two companies building the full-sized ones have the models in their place, and they’re working from them.”

Mollo’s costume sketches for Darth Vader include an insignia and a lightsaber with a broadsword handle.

Construction of the full-sized X-wing.

Reference photos of interesting junk, some of which became interesting props through the intermediary of John Barry’s art department.

Han Solo’s blaster.

Using set dresser Roger Christian’s technique of repurposing found objects into realistic-looking guns, prop makers fabricated what is perhaps a mock-up for a background gun.

A variation on Christian’s “Sterling Stormtrooper’s Gun,” it has the same T-strip for the barrel, but a different gun site and a small electronic greeblie.

The reverse side of Christian’s “Sterling Stormtrooper’s Gun,” which clearly shows the metal electronic box he added using superglue, as well as a short ammunition magazine he found and added.

A prop maker’s variation on Christian’s Mauser-inspired Han Solo blaster, which uses the same base but different greeblies.

“I made this one for the Tusken Raiders,” Christian would say. “I added the large round barrel silencer to give it a different look, and then attached a rubber line to the holster so it looked like a power pack for the gun.”

“It would be a lot easier if ILM were on the next-door stage,” Watts notes, “so we could just dash in and out, and there wasn’t an eight-hour time shift, and a shipping situation, and a communication problem. So the director could actually pop over there and say, ‘Yeah, that looks great,’ or whatever. This is the first time I’ve worked on a picture where the two powers of the show, as it were, are on different sides of the Atlantic: live action here and models on the other side. It’ll be interesting to see the end result …”

Set dresser Roger Christian explains how he designed Han Solo’s blaster, the prototype

weapon for all those that followed. (Interview by J. W. Rinzler, 2012)

(1:24)

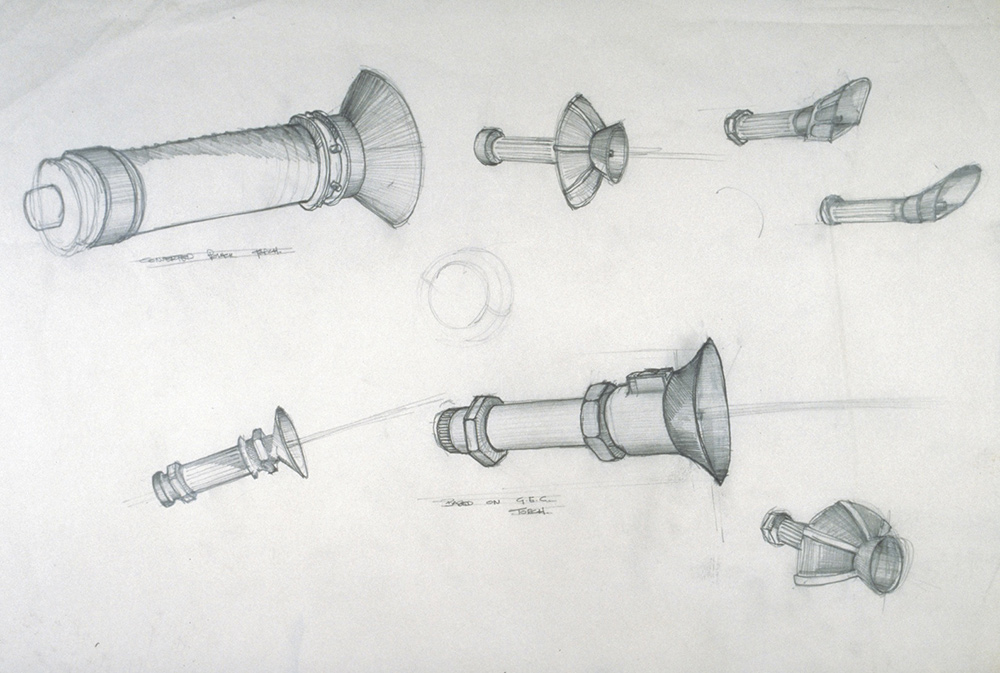

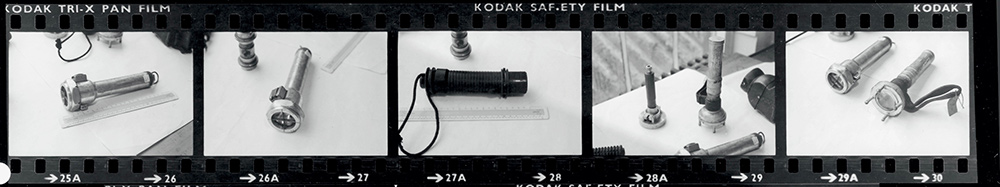

One of the side effects of working with ILM was to inspire Barry to go into the junk business. “ILM was basically using the same premise that had been used on 2001,” he says. “They used model kit parts to make their models look interesting. But I had to build full-scale seventy-feet-across versions of these things—but then it dawned on me that, of course, the actual kit parts represent real things, like crank shafts, so I could go back to the originals. So one of the first things we did on the picture was to buy thousands of pounds’ worth of junk from drain companies and the like—we have a buyer who’s a very eccentric and amusing man—and we invested £10,000 in a big machine that had previously been making dinghies and boats. The comlink is in fact part of a faucet. The handle of the lightsaber is a very old photographic flash unit, though we never just picked them up and used them. They were repainted, sign writing was put on, and sometimes they were cast again in plastic. Luke’s binoculars are an old Ronoflex.

“I took George to all the fun places,” Barry adds. “We went to one of the big weapon-hire companies that had endless rows of arms and armor. We found the gaffi sticks there; we just picked them off the wall, and took something off and whacked them a bit. George and the dresser, Roger Christian, and I got together a lot on those things. Rather than have your slick streamlined ray guns, we took actual World War II machine guns and cannibalized one into another. George likes what he calls the ‘visceral’ quality that real weapons have, so there are really quite large chunks of real weapons with additional things fixed onto them. It’s just so much nicer than anything you can make from scratch; it stops them from having that homemade look.”

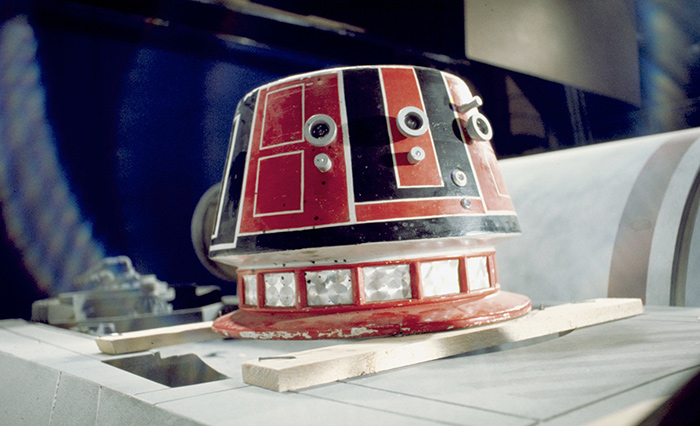

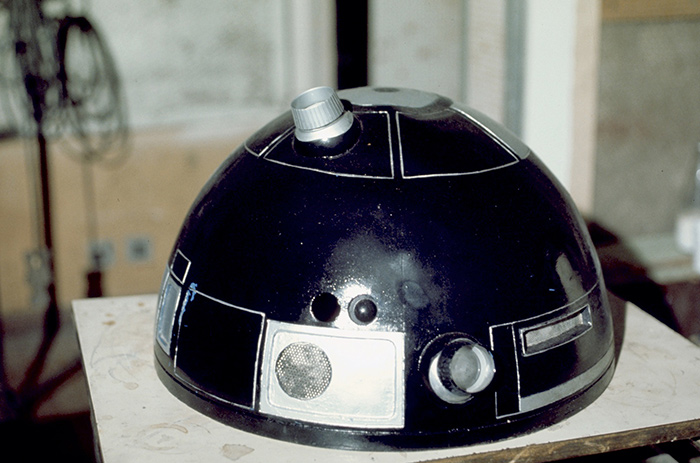

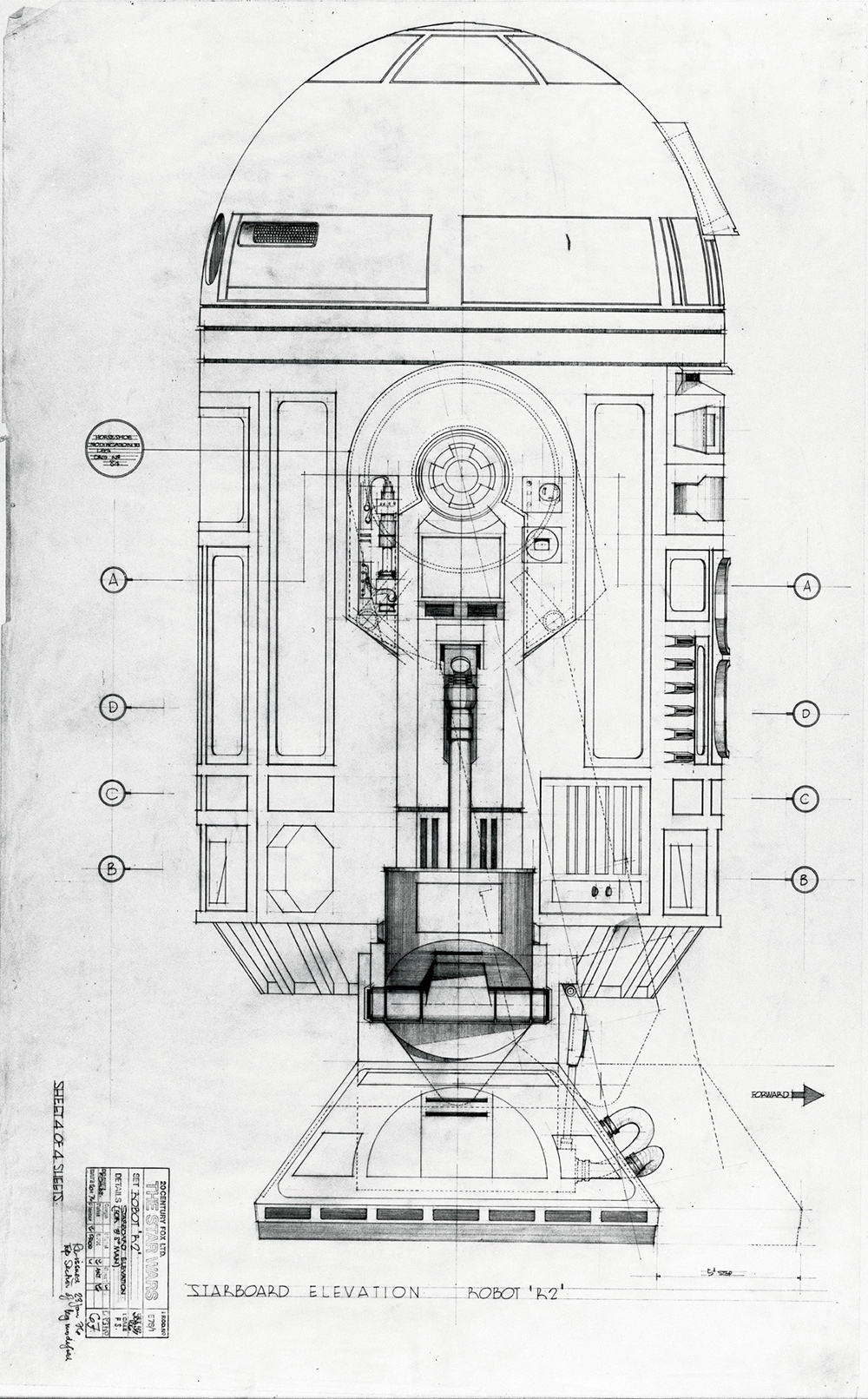

One of the first special effects tests at EMI concerned R2-D2, which became the model for several other robots in the film.

A blueprint for R2, dated January 20, 1976, drawn by P. Childs; a note indicates that the “top section of leg” has been modified.

Following the first special effects tests on January 14 with “laser swords, R2-D2 model, and illuminated control boards,” a second test took place on January 23 with “laser swords and Jawa ‘eyes.’ ” Between the two, Lucas sat down on January 20 with Kurtz and director of photography Gil Taylor, who at this point was quite new to the production and clearly coming to grips with many of its technical challenges.

On January 14, 1976, screen tests are filmed for “Artoo’s head.” (No audio)

(0:22)

George Lucas: As it stands now, we’ve got three scenes with the light sword. The first scene shows what it is: Luke just turns it on. The next one is a very quick scene in the cantina—it’ll just be a flash. In both those cases, it’s just one sword. The last is the final battle between Ben and the warlord. That’s going to be a tricky one where they actually fight, but at least now it’s down to a very controlled setup.

Gil Taylor: Are the laser sword and the laser gun one and the same thing?

John Stears

Lucas: No. Laser guns are going to be essentially real guns that fire a blank that makes a big flame. We’ll make it into a nice laser-gun sound later; then we will optically, in cases where it is necessary, animate the blasts, so you’ll see the bolts ricochet around. But you’ll never actually have to deal with it photographically.

Stears’ early concepts for the laser sword.

Production’s reference photos of early prototypes.

Mechanical effects supervisor John Stears (with beard and mustache) and others test

out early laser sword effects, circa January 23, 1976. (No audio)

(0:45)

Christian goes over how he created the first lightsaber prop. (Interview by Rinzler,

2012)

(2:14)

Lucas: The speeder is very low to the ground, like a hovercraft. It runs maybe a foot or two off the ground.

Taylor: I know it sounds outrageous, but if it was doing a lot of speed and you were shooting down like a railway track, you wouldn’t see much at all except a lot of things going by. Of course, I’m going back many years to a Hitchcock film, Number 17, in the 1930s—we had people fighting on railway carriages… [Taylor was a clapper loader on that film.]

Lucas: In a car on the salt flat you could go pretty fast.

Gary Kurtz: The ideal way to do it is a Wescam hanging from a helicopter, because it flies at fifty to sixty feet and it’s not affected by air pockets. The camera’s hanging down as close to the ground as you dare put it, and even if there’s a severe jolt the only thing that hits the ground is the camera and it’s in a bubble. It’s gyroscopic—have you ever seen one of these things in use?

Taylor: The thing is to get the right angle…

Lucas: If we had mirrors, or pieces of shiny metal, in front of the wheels, little plates tilted down, it would reflect the ground right underneath it and would help mask the wheels themselves.

Taylor: That sounds like it could work.

Kurtz: I hope we can find a stretch of road that meets the requirement—

Lucas: We found it. I don’t know what it’s like now—it’s rained there a lot—but it was fairly decent. It was a hard, scraped road; it wasn’t dusty. There was a problem with telephone poles, but we could mask those out. We don’t need that much, about twelve to fifteen seconds’ worth, a side view, a front plate going forward, and two side plates. The way the story is written now, there’s only one scene like this, and a couple of long shots.

Taylor: Is it an open cockpit?

Lucas: No, it’s closed.

Taylor: Oh, it’s all closed. So when you’ve got dialogue, where are you? Are you outside?

Lucas: We’d be outside.

Taylor: I see. Then there would be no wind as such and they would be completely air-conditioned inside.

Lucas: Yes. I want to be outside the ships, the fighters, as well, so we can see the reflections of light on their windshields, and use that as a device to create a sense of speed. I think we’ll probably do it on the speeder, too, because then we could have a really quick strobing, and shoot with a slightly long lens—not a real long lens, but long enough to lose a lot of the glass. We can shoot right through the glass. The thing of it is, no matter how fast you’re going along, clouds don’t move very fast. They won’t give you a sense of speed; whereas if we do it in the studio, we could fake something up that looked like it was going much faster. We have a whole lot of process shots with these ships, so we wanted to make some kind of rig that would change the key light drastically—it would zip all the way around, go from one side to the other side in a very short amount of time.

Kurtz: If the key light represents the sun, and the ship is flying along and suddenly turns, then the key light moves over here very quickly—if you’ve got some sort of a rig to move a single source of light across it. The other possibility that we came up with was to mount a whole raft of lights and have some sort of rheostat mechanism that would allow you to change from one to the other. The problem with incandescent lights is that they don’t heat up and die down quickly enough.

Lucas: I’ve discovered that the one thing that creates the illusion of movement is light. We cut the end battle scene out of all kinds of old war movies, everything from The Dam Busters and Battle of Britain [1969] to documentaries and Tora! Tora! Tora! And the one thing in the footage that makes it real is that the key lights change all the time. Even when they’re just flying along in a straight line, the light is never sitting there; it’s always rotating and moving. It’s really a nice feeling, even if it’s illogical. Even when you can’t figure out what’s going on, it’s nice to see that light dancing across the cockpit glass—there’s even a shot in one of those films where half the dashboard is all lit up and half is in dark shadow, and the shadow slowly moves up the dashboard. That’s a shot I want to get, where you play with the light inside of the ship as it flies around. Because this dogfight is going to be, hopefully, extremely quick. When we get into it, I want lots of flashing, strobing, and moving light, so the excitement continues from the exterior to the interior.

Lucas, Kurtz, and director of photography Gil Taylor discuss how they might shoot

some of the landspeeder shots from a moving vehicle. (Recorded on January 20, 1976)

(2:22)

Lucas: I want to rely on source lighting as much as we possibly can in the hangar, and design the source lighting into the sets. Things won’t be perfectly lit—we’ll have very hot spots and very dark spots, combined with the fact that I do want to get a soft edge. I want the film to be slightly filtered to give it a romantic quality. We have to find the simplest and easiest way of accomplishing everything, because we’ve got so many things to do. If we spend a lot of time trying to do something really complex, it’s going to bog us down.

Taylor: Are there going to be practical lamps in the big hangar?

Lucas: There are fluorescents or something. The main thing is that we want it to be very dark. We may want to rig a triangle light with a floodlight in the front. So you’d have a ship sitting there with a ring of these lights around it, shining up at it, these little floodlights that sit on the floor. We could use those on a couple of sets.

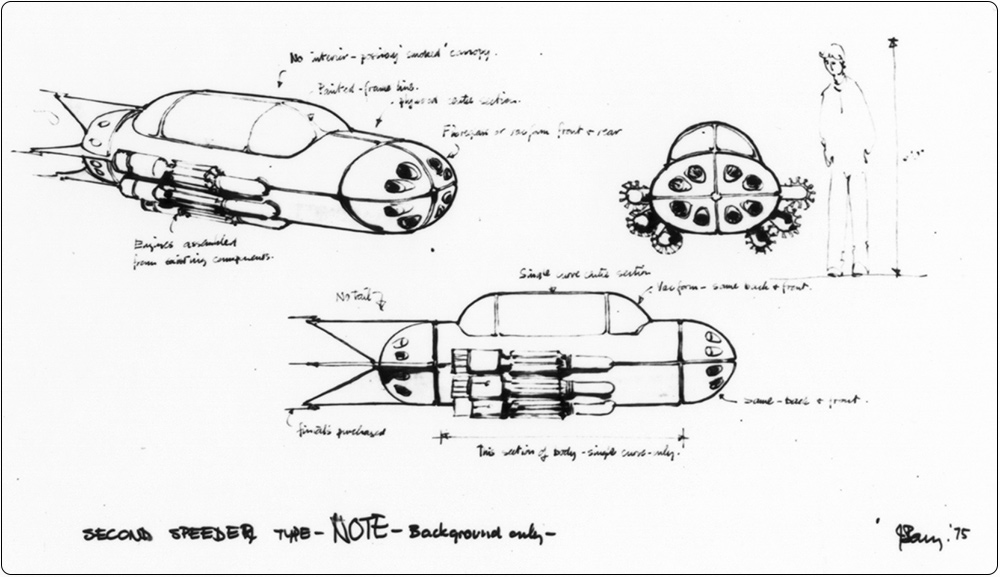

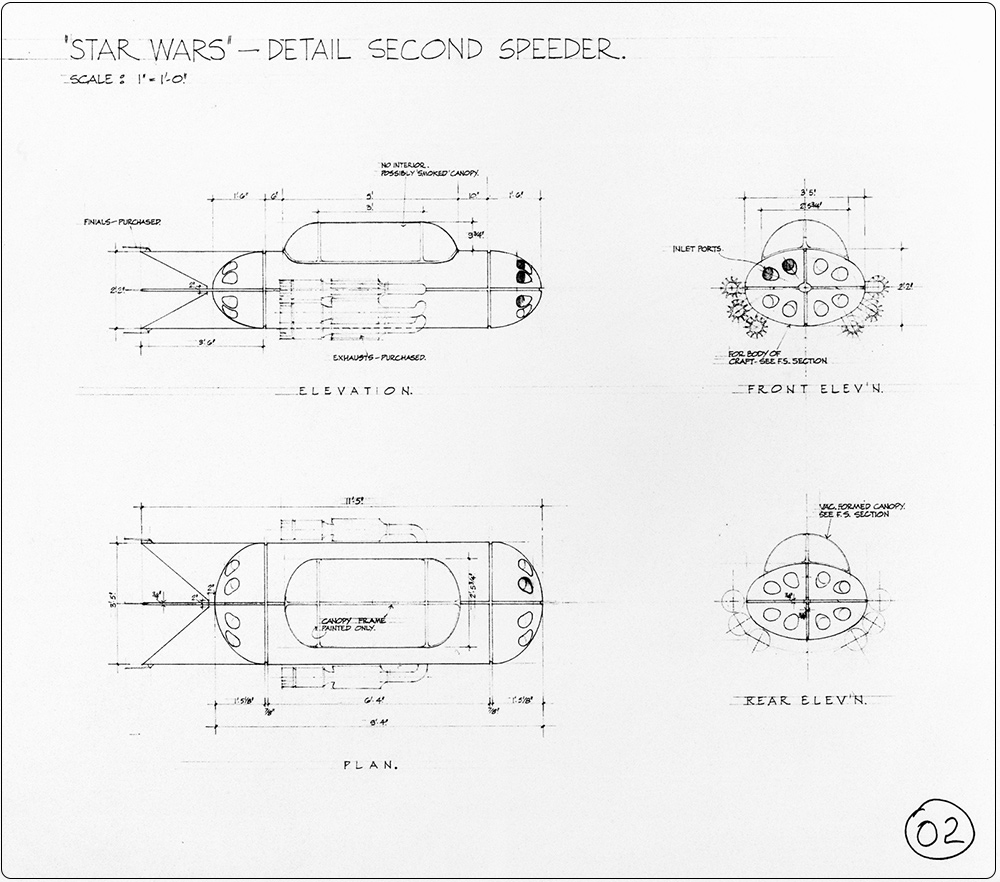

John Barry sketch for the “second” background landspeeder.

“Second” background landspeeder blueprint.

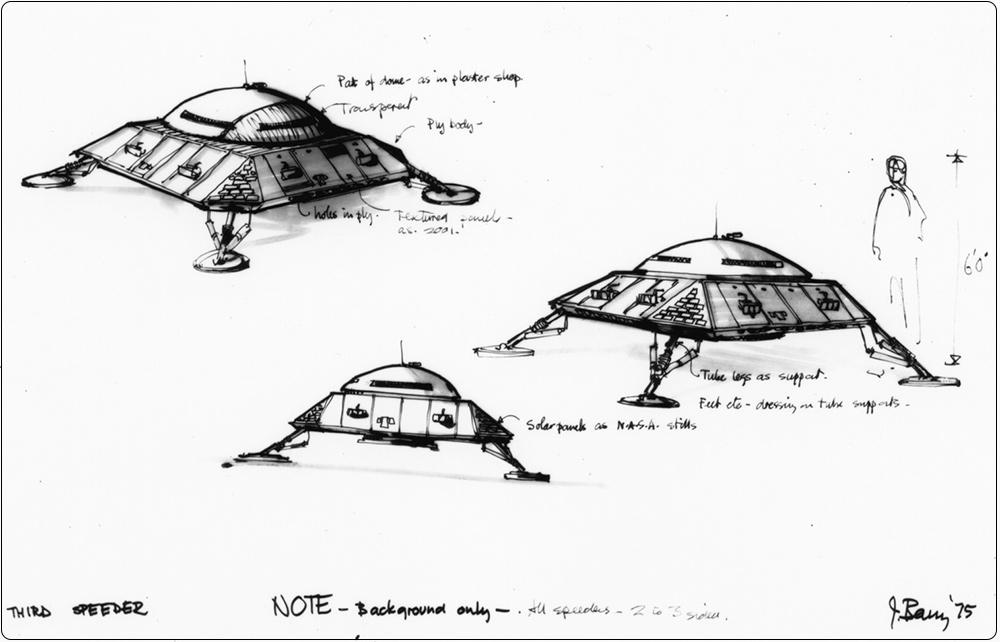

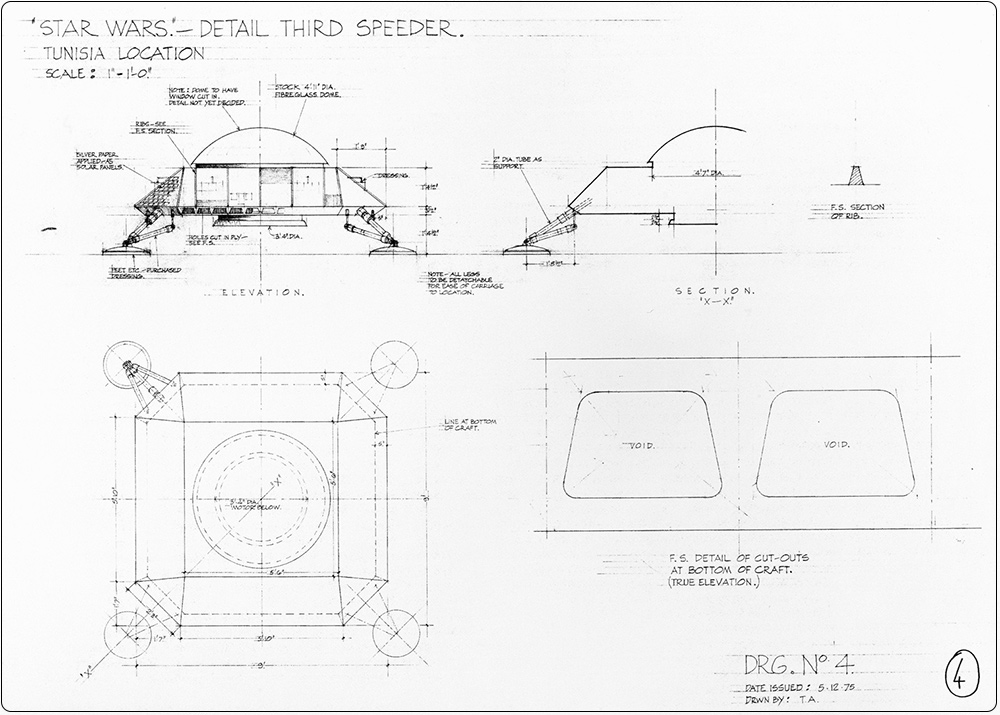

John Barry sketch for the “third” background landspeeder.

“Third” background landspeeder blueprint.

Taylor: But if that’s a painted cutout ship and I’ve got yellow lights, it’s going to make all this yellow, which we don’t want.

Lucas: We have a real ship. The circle lights will be cold, and the work lights will be very warm, so they’ll contrast. I’d like to have lots of lights, because that will work if we’re using a slightly filtered look—it’ll flare out and make everything look very complex. Combined with realistic source lighting and a slightly longer-than-normal lens, our backgrounds will be out of focus; I think, in a lot of cases, that will save us.

Kurtz: In this particular case, we’re going to move the extras around and shoot without touching the camera. Just shoot sectional pieces and have it matted together. The seven or eight matte shots will be filmed with the VistaVision camera locked down; all the rest will be shot normally.

Taylor: I wouldn’t have thought there was any studio big enough. Even the sound stage at Shepperton wouldn’t accommodate that.

Lucas: Well, we’re going to do it in this airplane hangar, so we have the length; we just don’t have the height. We’re going to try to double-expose the people, so that we have a whole lot of people, and then cover what’s left with a matte.

Taylor: We would have to—we can’t put in any big lamps, we’d probably have to accommodate that with the CSI-type lamp.

Lucas: Well, the scene can be much darker than it is in Ralph’s painting. The only thing that needs to be illuminated brightly would be this strip down the center, and if some of it kicked off onto the first and second rows … because if all of this goes dark, it saves us a lot of problems.

Taylor: Would that be a day scene?

Lucas: I don’t know. We were trying to decide whether we should do it day-for-night.

“Right around the end of 1975, all of a sudden this became a go-project,” Andy Rigrod remembers. “Then we started doing serious negotiations.”

The nine-page deal memo had to be transformed into a production-distribution contract, “which is a monstrous forty- to sixty-page document that formalizes the agreement by which a studio finances a motion picture, obtains certain rights in it, distributes the picture, and shares the profits with the filmmaker,” Rigrod explains. “From the very beginning there were tremendous amounts of negotiations with the studio.”

Although Twentieth Century-Fox was still calling the financial shots, by waiting so long the studio had actually managed to bargain itself into a corner. Thanks to American Graffiti, which by now had grossed more than $100 million and was one of the top ten moneymakers of all time, Lucas was a director to be reckoned with, who would normally receive greater pay. Fox had also antagonized the production by refusing to fund key elements of preproduction and by postponing negotiations—to the point where it was now the weaker party.

“The longer it took, the tougher we got,” Lucas says. “Because the longer they dillydallied, the more our stock went up—and the more it looked like we could make the film somewhere else if we really had to. We were willing to take it from them. It was at least two years after we got the deal memo that they finally drew up a contract, and during those two years things had changed. And I had written four scripts—they had only paid me for one—while the least they could have done in that time was crank out one contract. But I didn’t go back and say, I want to get paid for a rewrite; I want to get paid for each script. We left the deal memo intact. I left the money, I left the points, I left everything that was in the deal memo. But we did say, ‘You want to negotiate the contract now? We’ll negotiate the whole contract.’ ”

“Bill Immerman, who is the head of business affairs at Fox, and I handled the negotiations,” Pollock says. “But we did not renegotiate George’s money, which is what they had expected us to do. They had expected us to come back and say, If this movie is made, George should get $250,000 or $300,000 as a director, instead of $85,000, and he should get more points, and this, that, and the other. But George didn’t need the money anymore, so we went after all the things we wanted in the beginning but never had any chance of getting, because the studio never gives them up. Which is control—control over the making of the picture and control over the exploitation of all the ancillary rights.”

“Fox had been working on the assumption that we would accept their standard contract, while we had been working on the assumption that we weren’t going to accept anything,” Lucas adds. “We said, ‘This point isn’t right, and we don’t want this …’—and they were shocked because nobody had ever done that before.”

On February 1, 1976, the most formal budget so far was drawn up. The below-the-line budget was $6,568,932, with the total projected budget as $8,228,228; every last expense was itemized, and its cost projected into the future. Lucas was assigned $72,700 to direct and $50,000 to write, while his several trips to Los Angeles and London, his “Living Costs,” were reimbursed, totaling $8,210. His out-of-pocket costs were also covered by early 1976. The past was refunded, but the future was wide open. (Proof that things were happening in a somewhat chaotic manner, this budget still had remnants of items from previous drafts. For example, the Kiber Crystal had been budgeted for £300; two Sith Lords had costumes for £500 each; forty Aquillian rangers had costumes totaling £6,000; a Montross pirate outfit would cost £150—while an early address list notes that Bill Bailey had been cast as Montross, and Jay Benedict was to play Deak Starkiller—but only as an extra still carrying the name, as an in-joke, from the second draft.)

“You have to prepare for contingencies that may never happen,” Pollock continues. “What happens if the film goes $4 million over budget and Fox decides they want to take it over? You’ve got to fight that out now, otherwise you’ll have no rights later. What if they want to take it away from George and recut it? What are our rights? Everything is negotiated out, every possible contingency—and it takes forever. Andy Rigrod is really brilliant at that—that’s his strength in the firm.”

“There was an open area in the deal that was always more or less ambiguous,” Jeff Berg says, “that had to do with the notions of sequels and television, and publishing and merchandising and soundtrack: areas that were important to George because he knew the life of Star Wars would exist beyond the making of the first theatrical motion picture. So those were additional points that continued to be negotiated throughout the complete development phase of the project.”

“It was hard for Fox, at the time, to forecast two years down the line and say we shouldn’t give something up now if someone came in and offered a buck,” Jake Bloom says. “They had a historic way of merchandising films and it was hard for them to understand our client’s position. We weren’t interested in a buck—we were interested in preserving whatever rights we could and in making merchandising deals, if the upfront money justified the deal. We weren’t interested in making a blanket across-the-board merchandising deal, because we felt that if the picture was successful we would be selling out—and in the long run it would cost our client a fortune.” Within the film business, more prescient words may never have been spoken.

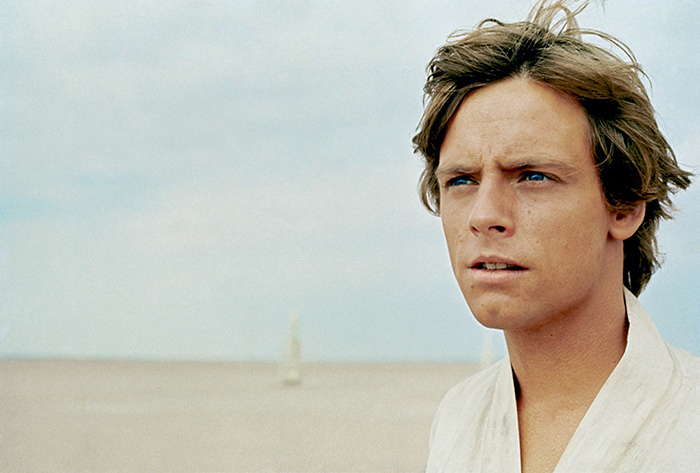

While hard-core negotiations began in the States, by late January, Lucas had decided on his final cast. After getting Guinness, Lucas chose Harrison Ford to play Han Solo, Mark Hamill to be Luke Starkiller, and Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia Organa.

“Harrison’s test was very good,” Lucas says. “I think he always had the edge because I liked him a lot in Graffiti; he had a quality. The Han Solo part wasn’t written for him, but I’d had him in my mind when I was writing it—even though I’d decided at one point that I wasn’t going to use anybody from the past. And I auditioned other people for that part. I had a black actor [Glynn Turman] who was one of the finalists and more heroic, and I had an older actor [Walken], who was the more maniacal of the group; Harrison was the funnier, goofier one—but he could also play mean. When I went younger with Mark, I decided I would also go younger with Han. The fact that I had Harrison in mind when I did the tests was helpful; he really worked well with Carrie and Mark—the combination was very good.”

Vice president of marketing and merchandising Charles Lippincott asks Lucas why he

chose Harrison Ford to play Han Solo. (Recorded on March 24, 1977)

(0:39)

Turman had also been recommended by Fred Roos, who had been “impressed” by his performance in Cooley High (1975), but Ford won out. “I’ve always had the feeling that I was hired for the job because I did the right thing for that character,” Ford says. “Acting is a matter of mechanics, and it was presumed I had sufficient capacity as an actor to handle the material, or was as close as George could get for the part.”

Although giving it a different chronology, Ford agrees that Luke and Han were cast as a duo. “I think George cast the relationship between Han and Luke,” he says. “That’s where George is a real student of human nature, ’cause he picked the kid automatically as soon as he picked me. I found it very easy to assume that relationship with Mark.”

“I try to cast it as a very good ensemble,” Lucas explains. “You think of it not only in terms of very good personalities who are going to work well on the screen, as good actors who are going to really be at the top of their craft, but also in terms of how all the actors interrelate as a group.”

The choice of Hamill also jibed well with the script. “If you read the original description of Luke, it’s almost exactly the way Mark is,” Lucas says. “In the end, it was between Mark and an actor who was a little bit older and a little bit more collegiate. He wore glasses; he was a little bit more intellectual. He was more like Kurt in American Graffiti, and Mark was a little younger, more idealistic, naïve, and hopeful; a little more Disney-esque.”

“My agent took me to lunch, and she was going down a list of business matters, like a grocery list,” Hamill says, “when in the very middle she said, ‘You have the part in Star Wars,’ and then she went on with the next item. ‘Wait a minute—back up!’ I interrupted.

“George chooses you for your personality,” adds Hamill, who was understandably shocked when he heard the news. “I mean, as a person, the actor is already so close to being the character. I’m not saying that’s true all of the time, but one phase of them is that character. I think if George would have had five more meetings with me, I wouldn’t have gotten the part.”

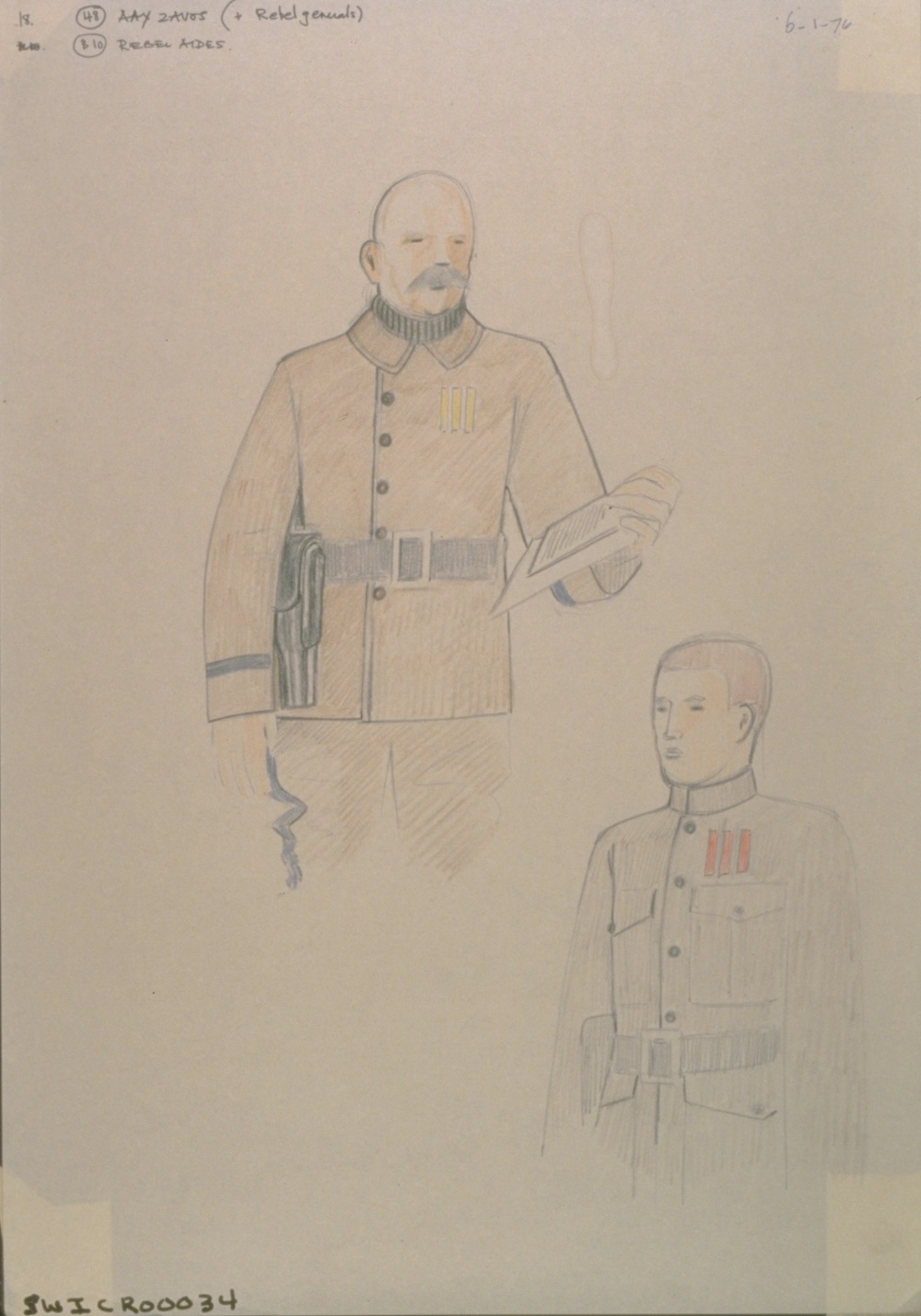

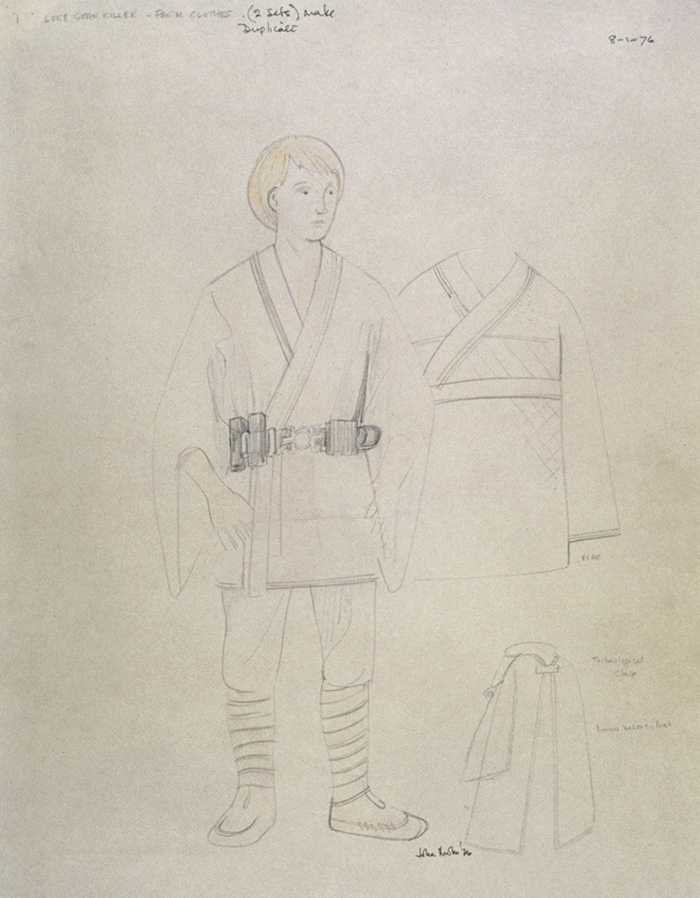

Mollo’s costume sketches for Luke.

Mollo’s costume sketches for Han Solo (right), and Ben Kenobi (left). “Luke wore a Japanese-type shirt with baggy pants and puttees,” he says. “George didn’t want any fastenings to show, he didn’t want to see buttons, he didn’t want to see zips, so we used stuff like Velcro, and things were just wrapped over and tied with a belt, or actually attached to the suede soft-leather boots. Ben Kenobi’s shirt is very much Russian.”

More costume sketches by John Mollo.

The last lead to be cast was Leia. “I had another girl who was much younger, who looked like what you might envision as a princess [Terri Nunn],” Lucas says. “She was very pretty and petite, but she also had an edge to her. Whereas Carrie is a very warm person; she’s a fun-loving, goofy kid who can also play a very hard, sophisticated, tough leader. This other girl couldn’t play sweet and goofy. Whereas with Carrie, if she played a tough person, somehow underneath it you knew that she really had a warm heart. So I cast it that way. The princess is one of the main characters, so the actress was going to have to be able to generate a lot of strength very quickly with limited resources available—and I thought Carrie could do it.”

“I ran outside in excitement,” says Fisher, “because I’d seen American Graffiti three times and liked it a lot.”

The budget benefited from the casting of unknowns. While Guinness’s long career and reputation earned him a substantial sum, Hamill’s weekly salary was $1,000, Fisher’s $850, and Ford’s $750. Another veteran English actor to receive more than his American counterparts was Peter Cushing, who was cast as Governor Tarkin and paid £2,000 per day. Apart from starring in dozens of Hammer horror films of varying quality during the 1960s, Cushing had started by playing bit parts in Hollywood films, such as James Whale’s The Man in the Iron Mask (1939) as well as Laurel and Hardy’s A Chump at Oxford (1940), later returning to England to play Osiric in Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948).

“The character of Tarkin, as I kept rewriting the script, kept evolving into a bigger and bigger part,” Lucas says. “And after we’d started designing the costumes, and I saw what Darth Vader looked like, I felt I really needed a human villain, too, because you can’t see Darth Vader’s face. I got a little nervous about it, so I wanted somebody really strong, a really good villain—and actually Peter Cushing was my first choice on that, once I’d decided we were really going to spend some money to go with a really good actor rather than just some stock day-player villain.”

“When you get to be my age and you’re still wanted, it gives you an awfully nice feeling,” Peter Cushing would tell Starlog magazine. “The older you get, the lonelier you feel. When you’re over sixty, you think you’re on the shelf.”

The last hurdle to the final cast was the United Kingdom itself, which had to be persuaded to let the American leads into the country. “The only problem that came up was the original equity problem about getting all three of the young actors into England,” Kurtz says. “We solved that through the Film Producers Association, saying, in effect, that we need a waiver on this because we have three hundred jobs at stake in England, and we have a lot of other actors that are locally hired. That was just a casual thing. They were willing to listen to reason.”

On the other side of the pond, ILM was making its first attempts at blowing up models. But the explosions were not looking good on film. One errant Y-wing even slid down a wire, detonated, and put a hole in John Dykstra’s leg. ILM’s predicament was not improved by the possible addition of the jungle planet Yavin to their list of imminently due front projection plates.

Another principal-photography-driven deadline involved computer graphics. “Gary and George had just left, and I was working with Jim Nelson, who was the only authority around here,” Ben Burtt recalls. “At this point my assignment was still rather vague. George and Gary gave me no goal, no quota, they didn’t need anything by a certain date. They more or less wanted something to listen to when they got back from England. So in the meantime I started working on other things—specifically, they needed computer graphics sent to England to run on those little screens on the sets and on the dashboards of the spaceships. So I was handling that for about three months at ILM; I had to find some animators to do it. Eventually, Dan O’Bannon took over, but Robbie Blalack and I found Larry Cuba.”

A Cal Arts graduate and already a pioneer in the use of computers to create animation, Cuba was awarded the contract in February and began work in March, with a June 1 deadline. His main task was to give the stolen Death Star plans a computer-graphics form for the big debriefing scene. “George knew enough about computer animation to specify the kind of things that he wanted,” Larry Cuba says. “He wanted the computer to look like it was really drawing the graphics. They also needed background screens moving all the time, and general computer activity.”

The key element of the plans was the trench run that led to the exhaust port, into which the rebels were to fire their torpedoes. “I visualized it as one continuous shot: coming upon the Death Star, flying toward the surface, entering the trench, going straight down the trench, and dropping the bomb at the end into the target,” Cuba says. “It turned out, for very technical reasons, to not be a trivial task to make all those continuous linkages from the different ways of rendering things.”

Before Cuba left for Chicago, where his equipment and setup were located, he went down to ILM for reference material. “I said, ‘Okay, where’s the trench that I’ve got to simulate on the computer?’ ” he recalls. “And someone said, ‘Over there,’ and pointed to a stack of boxes where pieces of the modules were just lying there. So I took one each of the modules.”

“I designed the Death Star modules,” Joe Johnston explains. “They represented, initially, the three trench stages. The theory was that at one end of the trench, where you first enter, there’s not much detail: the buildings are all low, and the trench is shallow and wide. But then as you get closer to the exhaust port, the trench becomes deeper and narrower, and the buildings higher and more detailed.”

“During the process a trench seemed to be forming at ILM,” Cuba says, “so Ben Burtt mailed me photographs that he’d taken to give me an idea of what the trench looked like. But there was no reason to match their design precisely.” In Chicago, Cuba set to work using his PT1145 “basic digital computer,” which was connected to a Mitchell camera with an animation motor. It would take two minutes to do a frame, for about two thousand frames, or three days of continual computer processing, to end up with ninety seconds of animation.

Ben Burtt was also busy doing his other job: collecting sounds. “George did not want anything in the picture to sound electronic, except maybe the robot language,” he says. “Electronic sounds had been in a sense a cliché in science-fiction movies. They wanted to avoid that and have as many organic sounds as possible—real sounds that existed and could be recorded in the world. You can’t beat the reality of sound like that. So I went to Marineland and spent some time recording the dolphins, seals, and sea lions. They were in the middle of draining the walrus pool one Saturday, so I went down there and recorded Petulia, a big walrus. A lot of her sounds became part of the Wookiee. Basically, the Wookiee ended up being a combination of Petulia and a young cinnamon bear by the name of Pooh, owned by a trainer in Tehachapi, California.

“The most interesting stuff came from a place here in Burbank called Pacific Airmotive,” Burtt continues. “It’s a company that builds and tests jet engines. You’ve got four isolated engines sitting in a wind tunnel, and they run up the engine and go into a lot of different maneuvers. I would bring the microphones in their test chambers and get everything from 747s down to helicopter and turbine engines. On a gunnery range in the Mojave Desert, where they actually strafed and were blowing up things, shooting rockets, I got some good material: explosions and swooshes and sounds that were used for some of the laser effects. I also had a friend who was a gun collector, from old black-powder guns up to M16s. We checked out about twenty weapons. We shot up the hillsides, got a lot of ricochets. I tried recording them in an unusual way by putting a mike near the gun and by putting a mike next to the target as well, so in stereo you’d hear the bang and the hit.”

Ben Burtt records Petulia in the drained walrus pool at Marineland.

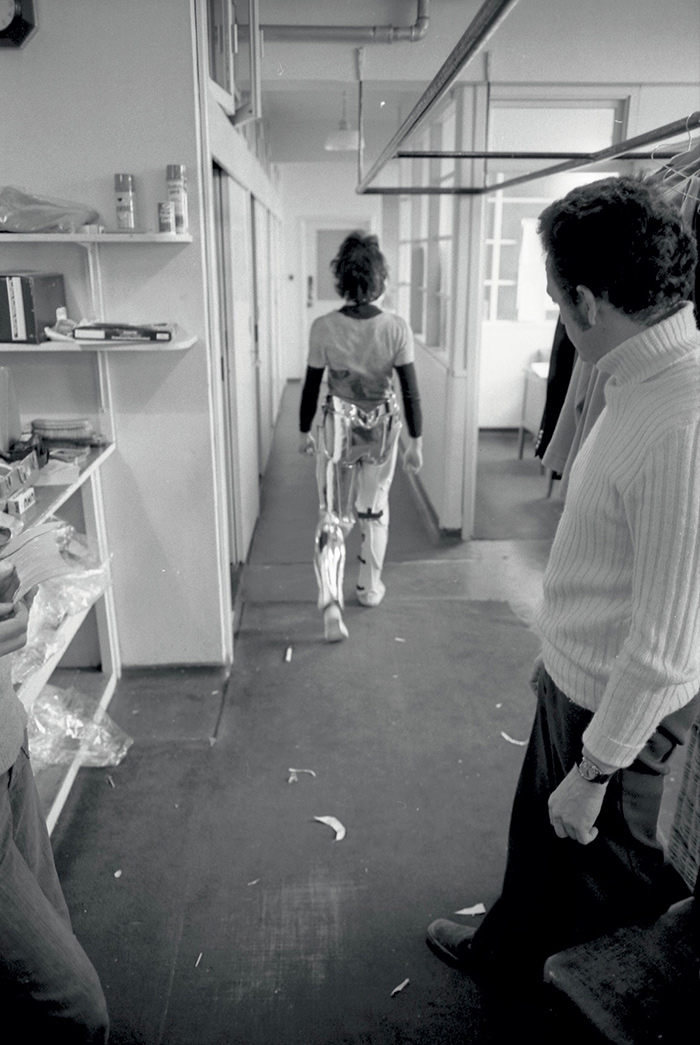

Several of the nine C-3PO faces sculpted by Liz Moore, with a variety of eye and mouth shapes, were photographed (above). Following the creation of the mold made from Anthony Daniels’ body (third set of photos), pieces were individually constructed, which the actor then tried on—testing, among other things, his ability to actually walk wearing his costume (below, with Liz Moore and Norman Reynolds observing).

Later Lucas and Barry puzzled as to how to attach the approved head design to the body.

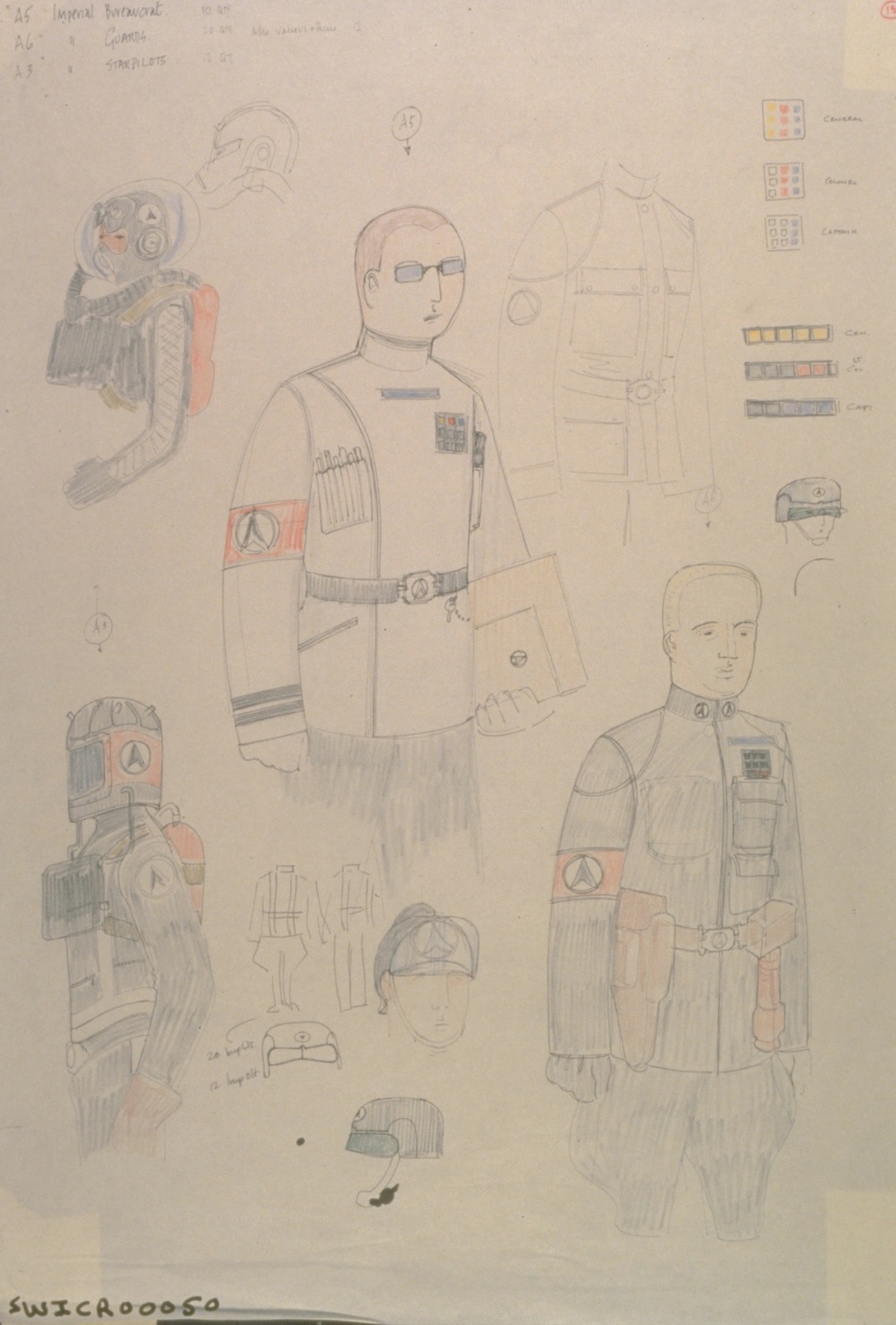

In England, Lucas and Mollo were busy creating the last costumes, with the latter being the next department head to be impressed by the former’s spartan directives. “George made pronouncements of a general nature,” Mollo says. “First of all, he wanted the Imperial people to look efficient, totalitarian, fascist; and the rebels, the goodies, to look like something out of a Western or the US Marines. He said, ‘You’ve got a very difficult job here, because I don’t want anyone to notice the costumes. They’ve got to look familiar, but not familiar at the same time.’ That was it! It then came down to asking George, ‘Well, is this color right, is this material right?’ and going from there.

Costume designer John Mollo on the first steps of transforming concept sketches into

physical costumes. (Interview by Arnold, 1979)

(1:04)

“We didn’t look at any films specifically, but had a lot of books—all the books there were on science fiction and science-fiction films, books on World War II, on Vietnam, and on Japanese armor,” he adds. “I started going around the area in London where all the electronics firms are and buying £20 worth of things. I would say, ‘You know, I’m going to be sticking this on a robot.’ ”

The one outfit for the film’s robot-like villain, Darth Vader, had a budget of £500 pounds ($1,173). “Vader was fixed in the McQuarrie painting,” Mollo says. “To realize that costume, Vader became a combined operation between the costumiers and us. The costumiers made the basic costume out of leather, while we in the studio made the masque, the armor, the belt, and the funny chest box with lights on it. To me it looks like a Nazi helmet and pieces of trench armor that they wore in World War I. So it wouldn’t be too hot and uncomfortable for the actor, we made it in pieces, so that you could take bits off quickly on the set.”

While Vader was to appear in only a few scenes, Anthony Daniels as C-3PO was going to be in nearly the whole picture. He also had only a single outfit, but it was budgeted at the much more grandiose sum of £7,750 ($18,189). The road to a finalized C-3PO design had begun with Lucas; gone through McQuarrie’s mind, then the shops of John Stears and John Barry, where Liz Moore took over; and finally returned to the hands of Lucas on February 11, 1976. “George had this concept of what the thing should look like, but I did a lot of very simple line drawings of little expressions,” Barry says. “Then George wanted to go for a slightly more humorous, silly look, so Liz Moore modeled nine faces. We stood them up at head height all the way around the stage, so that George could look at them, but they were kept well apart so that they didn’t interfere visually with one another. Then George, in fact, found two coins for the eyes, and we poked into the clay to make the mouth. He didn’t quite like the made-up mouth.”

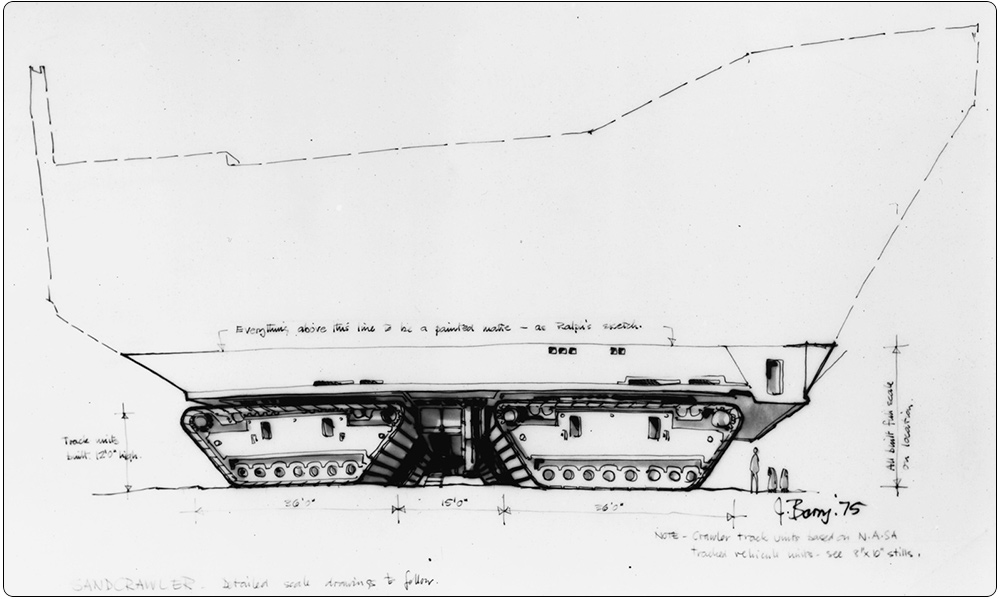

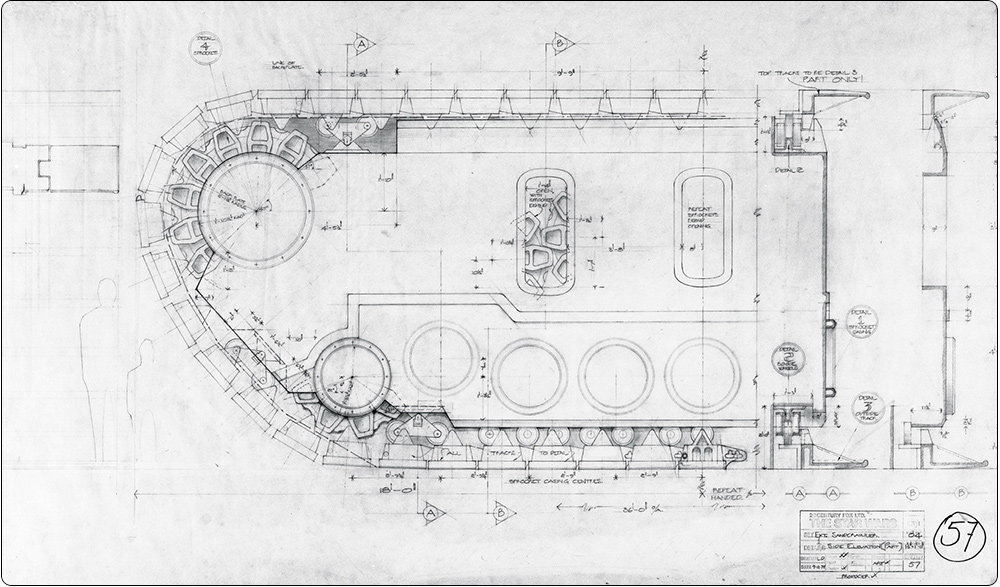

John Barry’s sketch of the sandcrawler.

John Barry’s sketch, based on the designs of McQuarrie and Johnston, helped his crew draw up blueprints for the sandcrawler base and tracks, dated December 9, 1975.

Ingenious production design enabled the wheel assemblies to be broken down and packed into trucks for transportation to Tunisia.

Following the costume show for Lucas, the art department concentrated on personalizing the robot exterior to fit its sole inhabitant. “They told me they had to cover me in plaster,” Daniels says. “The glamour of films really hit the dirt when I was standing there cold and shivering, with practically nothing on, and these two laborers came up with buckets of plaster and Vaseline. It was one of the most disgusting experiences in my life. They were very worried about doing my head because they said a lot of people faint. So they stuck a couple of straws up my nose. They said if you feel at all funny about it, wave your arms and we’ll yank you off straightaway.”

After creating the plaster molds from Daniels’s body, from which the metal pieces would be cast, the process hit a snag. “Unfortunately, a few days later they called me up and asked if I had a twisted spine,” he explains. “I didn’t think I had a twisted spine, but I went into the studio and there was this poor little warped me. The weight of the plaster had pulled me over. So I had to go through the whole body-cast process again. Fortunately Liz Moore was a love and made sure I was as comfortable as possible. She was very beautiful, and there I was wearing ladies’ tights wrapped up in sandwich foil, and she was slapping great jars of Nivea all over me. George kept coming in and fiddling around with my elbow or my knee or my shoulder, trying to work out how to make this garb work for a robot.”

A cover letter to Bunny Alsup, assistant to the producer, came with a copy of a press release sent out by Roadrunner Productions Ltd. in which they described, with breathless excitement, the departure of the first road trains—shown here waiting embarkation at Dover on their way to Tunisia—on February 16, 1976: “This is believed to be the first operation of its kind undertaken by a British haulier. Despite lack of time, the most meticulous planning has been necessary, particularly with regard to customs documentation … Within a matter of days, the first convoy of three drawbar pantechnicons and one specially constructed scenery van, with a combined capacity of 24,000 cu ft, was en route to Calais …”

Throughout the first quarter of 1976, Lucas somehow managed to find time, as usual before dawn, to revise his fourth draft into what would be the shooting script. Most of his changes occur in the first two-thirds. However, no matter how much Lucas worked on the spoken parts, they failed to impress him. He decided to hire his screenwriting friends Gloria and Willard Huyck for their verbal expertise. “Just before I started to shoot I asked them to help me rework some of the dialogue,” Lucas says. “At the very last minute, when I’d finally finished the screenplay, I looked at it and wasn’t happy with the dialogue I had written. Some of it was all right, but I felt it could be improved, so I had Bill and Gloria help me come up with some snappy one-liners.”

“I met George at USC, when we were both in film school,” Willard Huyck remembers. “A friend of mine and I had made a short film and it got stuck in the lab because we didn’t have the $80 to get it out. George was working at a commercial house on weekends, and I didn’t know him that well—but out of nowhere, he said, ‘You know, I’ve got the $80 and I heard that you couldn’t get your film out of the lab.’ So I thought this was such a wonderful thing to do, and we became friends after that.”

Lucas and the Huycks had already collaborated on American Graffiti and the development of Radioland Murders, so they had a solid working relationship that was actually built upon, at least in Willard’s case, a similar upbringing. “Willard and I come from exactly the same background,” Lucas says. “He came from San Fernando Valley, and his father is almost like my father. Same small-business owner. Small town. Middle-class WASPs. We are of the same social, economic, religious group, and we therefore relate on a lot of levels; there are a lot of similar things we understand and are amused by.”

Already familiar with the film, having read several of the previous drafts, the Huycks tightened and lightened the dialogue, while Lucas remained fundamentally frustrated by the whole experience of authoring The Star Wars. “It’s very hard to write about nothing,” he says. “Graffiti, I wrote in three weeks. This one took me three years. Graffiti was just my life, and I wrote it down. But this, I didn’t know anything about. I had a lot of vague concepts, but I didn’t really know where to go with it, and I’ve never fully resolved it. It’s very hard stumbling across the desert, picking up rocks, not knowing what I’m looking for, and knowing the rock that I’ve got is not the rock I’m looking for. I kept simplifying it, and I kept having people read it, and I kept trying to get a more cohesive story—but I’m still not very happy with the script. I never have been.”

Two weeks before shooting was to begin, the last of the road trains left for Tunisia—without the landspeeder and robots, however, because they were still not ready. The first road train had departed the end of January, and the second in February. Each journey took five days, by ferry to France, by road to Italy, by ferry from Genoa to Tunis, then by road from Tunis to Djerba in trucks—twelve trucks total. The first construction crew was already in Tunisia for six weeks of prep.

The production crew brought with them four Land Rovers, a mobile kitchen, tons of equipment, and, of course, the sets. “I designed the sets that went out on location so that they nested one inside the other, so that we would get a lot on the trucks,” Barry says. “I made the track units of the sandcrawler in three sections so that we could get them one folded up inside the other—because if it won’t go on the truck and it won’t go over the hill, then it won’t be in the film. It’s those sorts of considerations that really pin you down.”

Three weeks before shooting began, all of this carefully if frenetically planned work almost became a lost cause. Because back in the United States, negotiations between the Star Wars Corporation and Fox were dragging on and on, up to the beginning of March—at which point Lucas had to call their bluff. A number of elements, which Kurtz characterized as “deal breakers,” were fueling the fire: 1) a dispute over who should pay $45,000 in legal fees; 2) still unsigned agreements that affected the chain of title to the picture; and of course 3) all of the details inherent in the production-distribution contract.

“About three weeks before we were going to shoot, I gave Fox an ultimatum,” Lucas says. “I said, ‘I’m not going to start shooting this picture until all these outstanding points are agreed upon.’ Because once I’d started the picture, they would’ve had me. Once you start shooting, you don’t have any more leverage.”

In late February 1976, Kurtz flew to LA and met with Alan Ladd. Following the meeting Kurtz called Andy Rigrod, telling him he wanted Tom Pollock and Jeff Berg to talk with Ladd and Dennis Stanfill, chairman of the board of directors, and obtain their verbal commitment that Fox would pay the $45,000. Rigrod’s notes reveal that, if these issues were not resolved, Kurtz and Lucas were ready to “fly back”—i.e., abandon the picture. Now that Fox had invested heavily in the film, this was a serious threat—which was made doubly so given the last and most critical piece to the legal puzzle: the American Security Interest and the British “Charge”—two pieces of insurance essential to Fox’s ownership of the film, both of which were in peril because the studio had no signed agreements.

For two weeks, negotiations must have hit high gear—because seven days before Lucas was either going to shut down production or board a plane for Tunisia, Fox blinked. Compromises were reached, and though they didn’t have the exact language for the final production-distribution contract, the studio gave in to Lucas’s main demands. Pollock signed key papers on behalf of the Star Wars Corporation to help Fox, which agreed to pay the legal fees, and Lucas signed agreements formalizing his directing and writing services, which gave Fox its desperately needed “chain of title.”

“It wasn’t until a week before we started shooting,” Lucas says. “Gary went over and got the agreement, brought it back, and I signed it.”

In this Mollo costume sketch, Solo’s costume directions are: “T-shirt, long sleeves, black jeans, yellow stripe into boot.”