As last-minute preparations were made during the final few days in London, Alan Ladd, newly appointed as Fox’s senior vice-president in charge of worldwide production, arrived from Los Angeles to go over some “final points” with Lucas and Kurtz. One dilemma was that ILM was behind. “They hadn’t done any special effects,” Lucas says. “ILM was supposed to have all the plates for the front projection with the spaceships done by the time we started. It was a key part of the production schedule—but they only had about three of them.”

Into this high-tension situation came the first of the leads. “The whole thing was such a parallel of the film,” says Mark Hamill, former short-order cook at McDonald’s, ice cream scooper at Baskin-Robbins, and copyboy at Associated Press. “Here I am, off on this great adventure to make this movie. I had never been to England, never been to Africa. I was on the plane, and we came down through the clouds, and I saw all of those quaint houses. After landing, I was anxious to hear people talk with their English dialects. Someone picked me up and we went to the hotel. I put my bags down, took a shower, and went straight out to have a costume fitting. The next day they took me over to EMI where I met George and Gary. I was scared of them.

“George took me around and showed me all of the sets,” he continues. “They weren’t painted or anything; the Millennium Falcon was just wood. You can’t imagine how it’s going to look. And he’s explaining all of these things—‘We’re going to shoot the exterior here and when you walk into the house, this is where you’ll be’—and jet lag is setting in while I’m meeting all of the crew. Then George says, ‘Do you want to go and see some test footage of the robots?’ I said sure and we went to the screening room, and they were all waiting for George. And George says, ‘Oh, this is Luke Starkiller.’ Everybody just went ‘Oh’ and went back to their job, and I fell into a chair. It was really exciting, but no one cared. They were all blasé. I was really interested in what was going on, but I just couldn’t keep my eyes open.

“Afterward, I left to go back to my hotel—and got lost. I thought I’d walk around and see things. Well, nothing’s on a grid in England. Three hours later, I’m still trying to find my hotel. It got so bad that I tried to get help in another hotel. I’m looking through my wallet for something, a matchbook, and they’re starting to get very worried—with the Tube bombings and the IRA—so they want my passport number. But I couldn’t think of it, so they called the police. And I’m sitting there with the police in a paddy wagon, and they’re asking, ‘Was it the Dorchester? The Grosvenor Square?’ Finally, magically, we hit upon it.”

As Ladd and Kurtz finalized cost estimates, the wardrobe budget came out to about £90,000 ($220,000). “In fact it was really quite a comfortable budget,” Mollo says. “The materials that were used were so cheap, you see.” One item that stood out, however, was the cost associated with the stormtroopers, who ran up a tab of £40,000 ($93,000)—and whose final outfits were still not ready a week before location shooting was to begin. “Stormtroopers were the nightmare costume,” Mollo explains. “We got a model in of suitable size, did a plaster body cast, and a sculptor modeled the armor onto this figure. Then everybody used to go in and say, ‘Arm off here, arm off there,’ and George changed all the kneecaps. This went on for several weeks. Finally that was all taken away and produced in vacuum-form plastic—but the next question was: How does it all go together? And I think we had something like four days before shooting, but we just played around until we managed to string it all together in such a way that you could get it on or off the bloke in about five minutes.

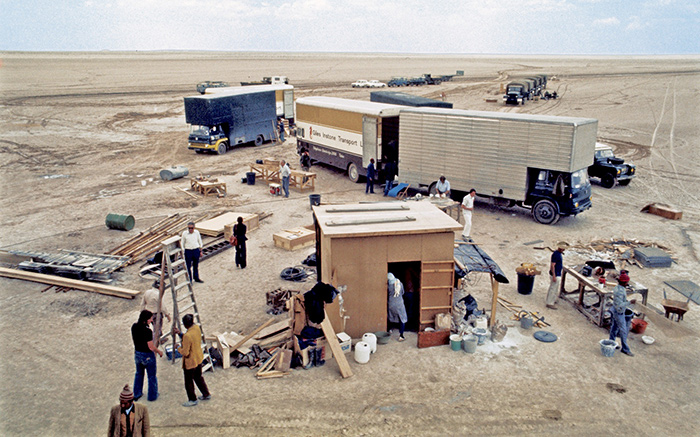

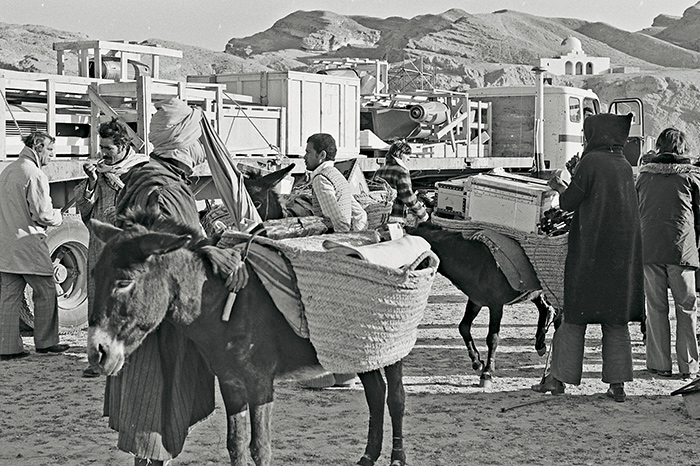

While last-minute preparations were completed in England, last-minute construction of the sandcrawler and other sets were under way in Tunisia, with the arrival of the road trains from England—though even mules were necessary for additional transportation.

“On top of all this, George announced that he was going to take some stormtroopers on location, and he wanted them to be in ‘combat order.’ I said, ‘Oh yes, George, what’s combat order for stormtroopers?’ and he said, ‘Lots of stuff on the back.’ So I went into this Boy Scout shop in London and bought one of these metal backpack racks; then we took plastic seed boxes, stuck two of those together, and put four of those on the rack. Then we put a plastic drainpipe on the top, with a laboratory pipe on the side, and everything was sprayed black. [laughs] This was the most amazing kind of film! George asked, ‘Can we have something that shows their rank?’ So we took a motorcyclist chest protector and put one of them on their shoulders. George said, ‘That’s great!’ We painted one orange and one black, and that was it!” Mollo concludes, happily.

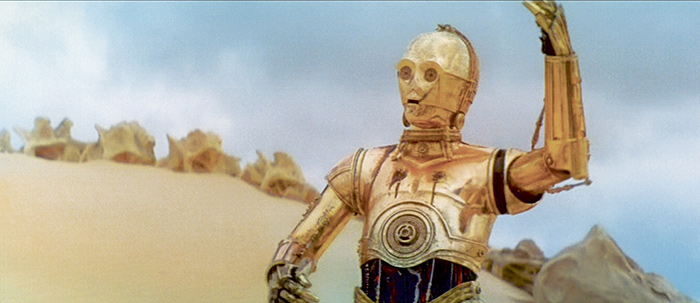

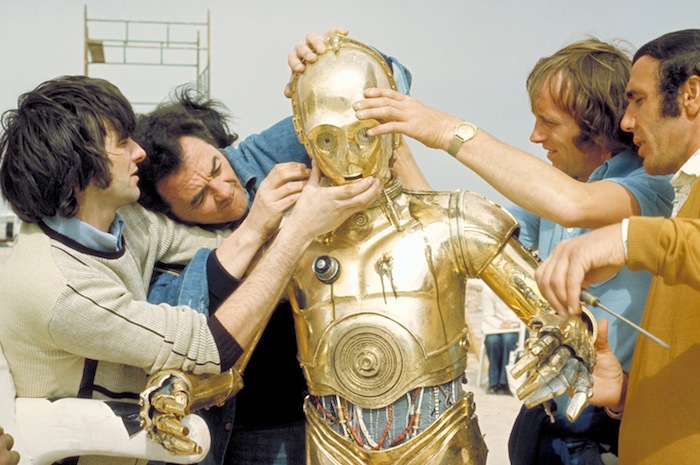

Last-minute solutions were also found for the C-3PO costume. “They finally did hit on specially engineered wheels and rings that fit in beautifully with each other,” Daniels says. “But all this took so long that I only put on the complete costume once, just before we flew to Tunisia.”

One of the major cost overruns occurred because these sort of final adjustments were being made so late, due to the studio moratorium. Certain sets and equipment didn’t make the last road train, which would’ve cost around $5,000. Instead production had to charter a Lockheed Hercules C-130 aircraft at a cost of $22,000, round trip, for the last shipment just two days before shooting began.

To celebrate their impending adventure, Lucas and Kurtz threw a cocktail party for the cast and crew at the Hotel Africa in the Maghreb room on March 17 at 6:30 PM. “I guess I came in on Tuesday,” Hamill says. “Thursday I had off. Friday, I had lunch with George and Gary in a Chinese place. Then the big day arrived. It was Saturday, March 20: We were down at Heathrow Airport and were ready to zip out to Tunisia. That was the first time I saw any of the crew that were going to be shooting. That was fun. That was like field-trip day. You got your bags with STAR WARS stickers on them. I thought to myself, ‘I’m going to Africa!’ And off we went.”

Lucas, Hamill, Daniels, and company flew from London to Djerba on a chartered British Airways flight. That night was a layover before they continued by car and truck to Nefta. The week before, Anthony Daniels had been playing in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead at the Criterion Theatre in Piccadilly Circus. “It’s a very taxing play,” he says. “But I still didn’t sleep the first night in Tunisia, because there were a lot of German tourists trying to find their rooms at four in the morning, and we had to get up at six.”

“We landed in Djerba, and there was a huge hotel complex,” Hamill says. “Four hotels all next to each other—you could get lost on the way to your room. It was insane. It was all one story, just spread out. Golf courses, restaurants, discothèques—I thought, Is this what Africa is going to be like? But the next day we started out real early and drove forever in the rain to the salt flats.”

At Nefta, the biggest nearby town was Tozeur, “which was tiny,” Robert Watts says. No stranger to location shooting, Watts had handled productions all over the world, including Japan, Finland, Spain, Germany, Colombia, and the Kalahari Desert. “A lot of nomadic people used to come out of the Sahara, these black-dressed Berber women who still cover their faces. You can only see one eye like that. And they were a terrible hassle at night driving through the town because you couldn’t see them.”

After running smack into the bargain-tour crowd in Djerba, the newly arrived crew had to deal with the Franco Zeffirelli television production of Jesus of Nazareth (1977), which was also lodged in Tozeur. “It was a twelve-hour miniseries,” Kurtz says. “And they had used up all the local technicians, all of the plaster and rental cars—and all of the hotel space. The big hotel was closed due to remodeling, so people had to double and triple up, and stay in fourth-rate hotels. That was okay for two weeks. We could survive that. But if it had been two or three months, we would have had a riot on our hands.”

The Star Wars location crew numbered about a hundred people from England and twenty-five Tunisians. The two groups communicated in French, primarily through the assistant directors and the Arabs from Tunis, as Tunisia used to be a French colony. The night of Sunday, March 21, those who could got some sleep in their cramped quarters, preparing for a production that had already been almost three years in the works, but still wasn’t ready for prime time.

REPORT NO. 1: MONDAY, MARCH 22, 1976

CALL: 06.30; SALT FLATS AT NEFTA; SETS: EXT. LARS’ HOMESTEAD; SCENE NUMBERS: 26 PART [PURCHASE OF C-3PO AND R2-D2]; 29 PART [LUKE AND GIANT TWIN SUNS]; B29 [LUKE AND C-3PO RUSH OUT OF HOMESTEAD TO LOOK FOR R2-D2]

Note: Not every scene shot is listed; some scenes were shot over several days, which is signified by “Part” or “PT.”

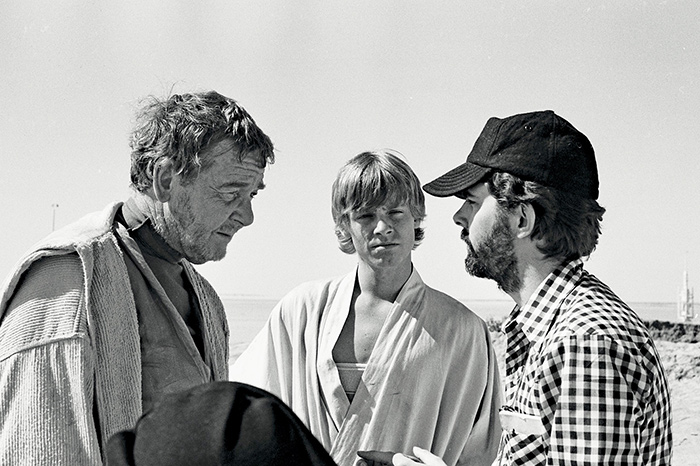

Lucas talks to Phil Brown (Owen) and Mark Hamill (Luke).

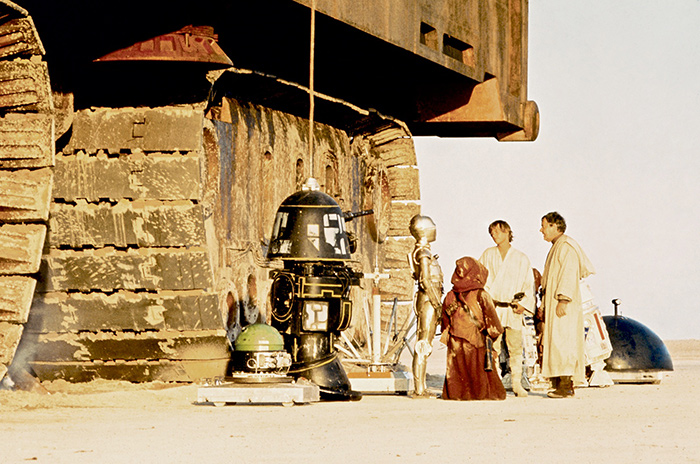

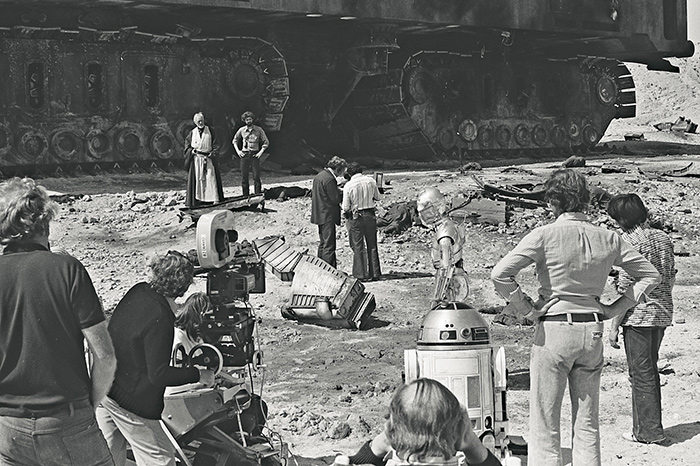

Cast and crew arrived on the salt flats at Nefta, where the sandcrawler partial set was ready for them. Lucas needed only the bottom portion for his location shoot, including scene 26, in which Owen Lars purchases the robots.

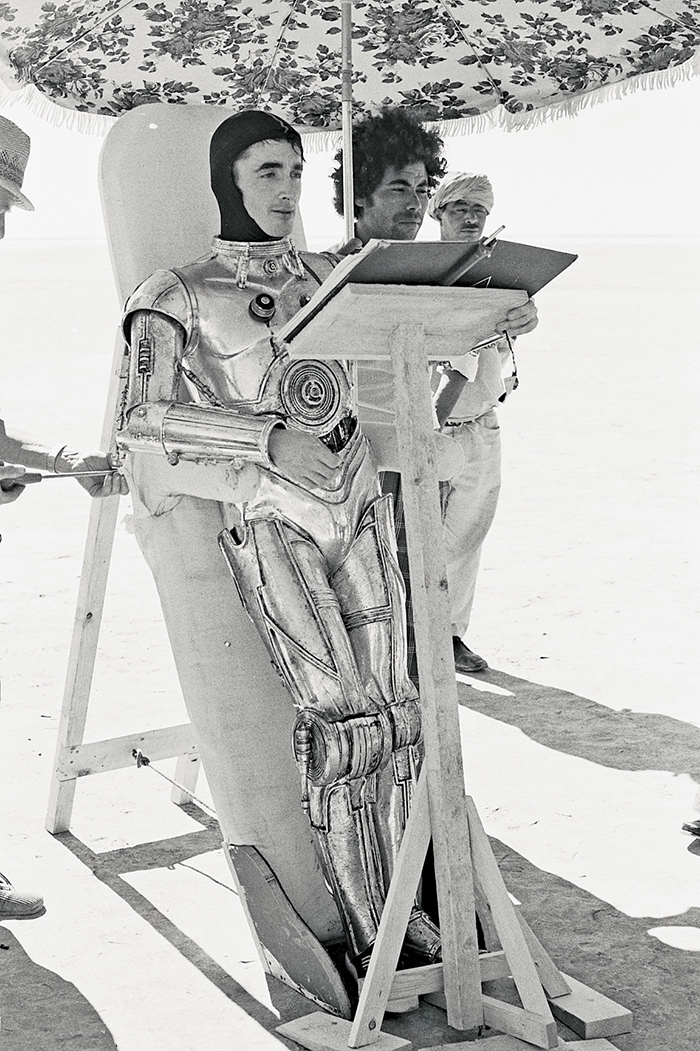

Anthony Daniels: “I saw a chair one day and it said ANTHONY DANIELS on the back of it, and I was very excited about that. But I never got to sit in the chair because I could never sit down. I had this terrible leaning board, a kind of medieval thing with arms that allowed me to recline at about seventy degrees, which was very little use at all, because the weight still went down to your ankles. I wore ordinary nylon leotards and tights and some very nasty little sailing shoes from Libby White’s in London—I wore one pair throughout the film, and they got very battered. I had gold shoes under the gold legs, which went up onto a pair of trousers made of fairly thick plastic bolted together at the hip. It had a rather large crotch, which I think George liked to define as ‘space eroticism.’ And then I had a kind of corset, which was made of very thick rubber and sewed by hand. It had lots of spare wires and junk, which during the course of the film changes incredibly. Fitting above that is a front and back piece. The front piece contains the left armhole and the back piece contains the right. The arms were slid up and hooked on the shoulder. The hands were special gloves made by a sculptor who decided that they should be sheet steel. The first time I put them on, I could hold my hand up for about twenty seconds before it would clunk on the table. They were so heavy, I said they had to make me something else. That was an example of production gone haywire.”

Anthony Daniels as C-3PO being attended to by production on location.

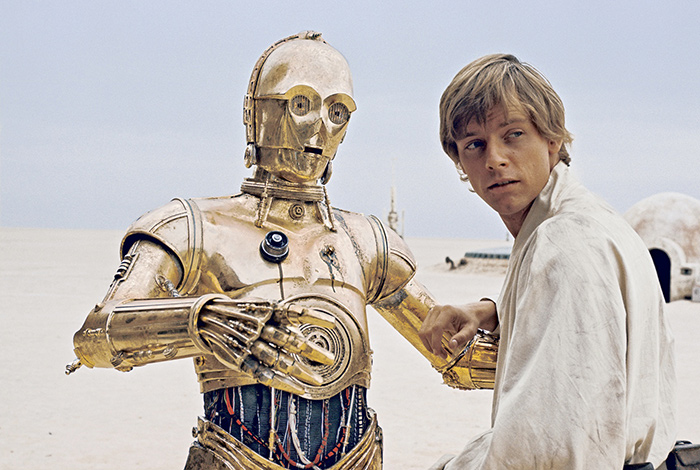

The first day’s scenes featured Hamill, Daniels, Kenny Baker in the R2-D2 shell, and Phil Brown as Uncle Owen. Lucas’s notes reveal that Brown was cast because he was a “good Owen-type, a scruffy American”—something that Brown could relate to. “Uncle Owen was a straightforward curmudgeon—which I am anyway,” Brown says.

The day’s most complicated scene was the purchase of the robots. Extras included twelve local children as Jawas. Struggling to join them was a tired Daniels. “I couldn’t sleep in Nefta, either,” he says. “The first morning of filming I was so tired, I didn’t care at all about anything. The final costume took two hours to put on. It fit tightly. Two bolts went into the neck, and it was bolted just above the waist, so there was no way on earth that I could get out of that thing. It was precision-engineered, and if I got in the way, I got very badly cut up. By the time I walked ten paces out of the tent on the Tunisian salt flat, it hurt so much that I couldn’t make it to the set about three hundred yards away. I kind of hobbled and lurched over to the set and we began filming—but I just felt I wasn’t going to make it through the film.”

Hamill, on the other hand, was enjoying the first day. “It was really great,” he says. “All of that stuff was supposedly happening on my planet, Tatooine, so there was a modicum of continuity. That was the beginning of the movie and I really got to know Threepio, the actor playing him, as well as the character. It was real easy; it was like it was happening in the film.”

As the sun rose, Daniels, encased in his armor, learned a valuable lesson. “On the first day’s shooting, the script had a lot of technical vocabulary. I had to say ‘binary loadlifters,’ which I still can’t say. And we must have done quite a few takes before it occurred to me that it didn’t matter what I said, because my lips weren’t moving.”

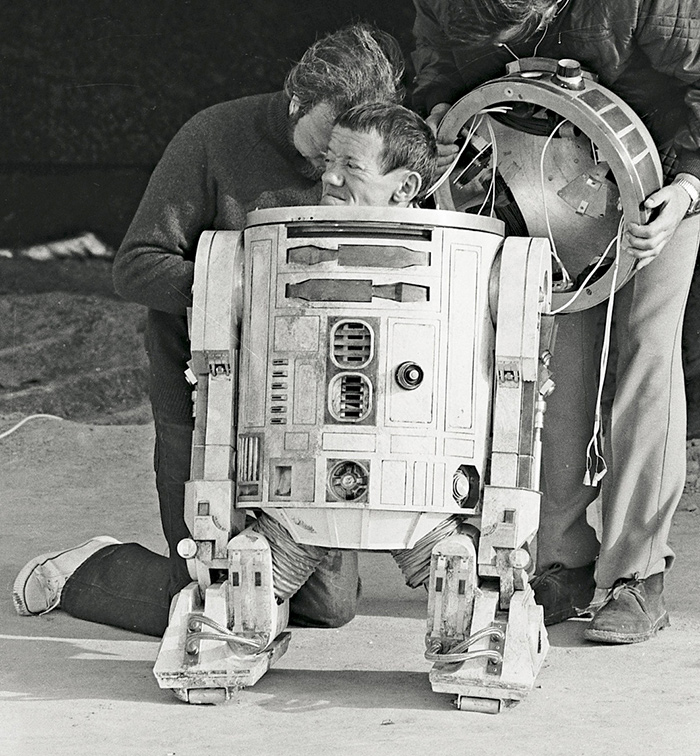

While Daniels resolved one problem, however, others waiting in the wings came to the fore. “Things started to go wrong,” Kurtz says. “The Artoo unit was not working right, the batteries would run down too early, and they were hard to replace. The kick-down leg didn’t work, and the head didn’t turn right. The very first day we had that sequence where Uncle Owen picks the red robot and Luke walks away and says, ‘Come on, Red!’—and the red one is supposed to roll out there and its head is supposed to blow up. Well, the radio-controlled robot had all the controls in the head, so we couldn’t put the exploding head on it.

Problems with the robots began on the first day. “Red” is unpacked, with one of production’s Land Rovers behind it.

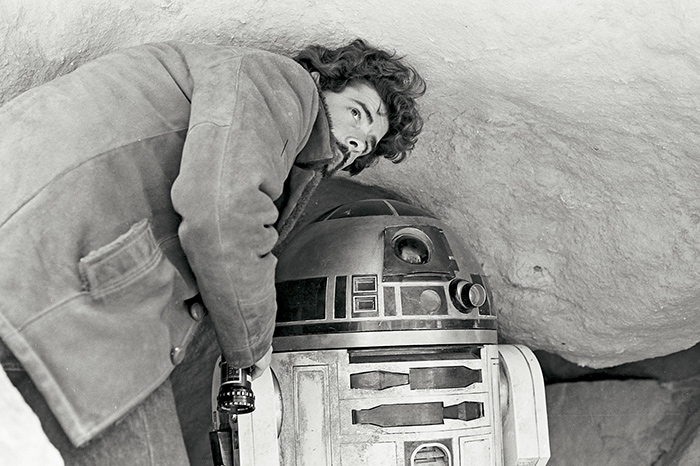

Kenny Baker also did his best to make R2-D2 function.

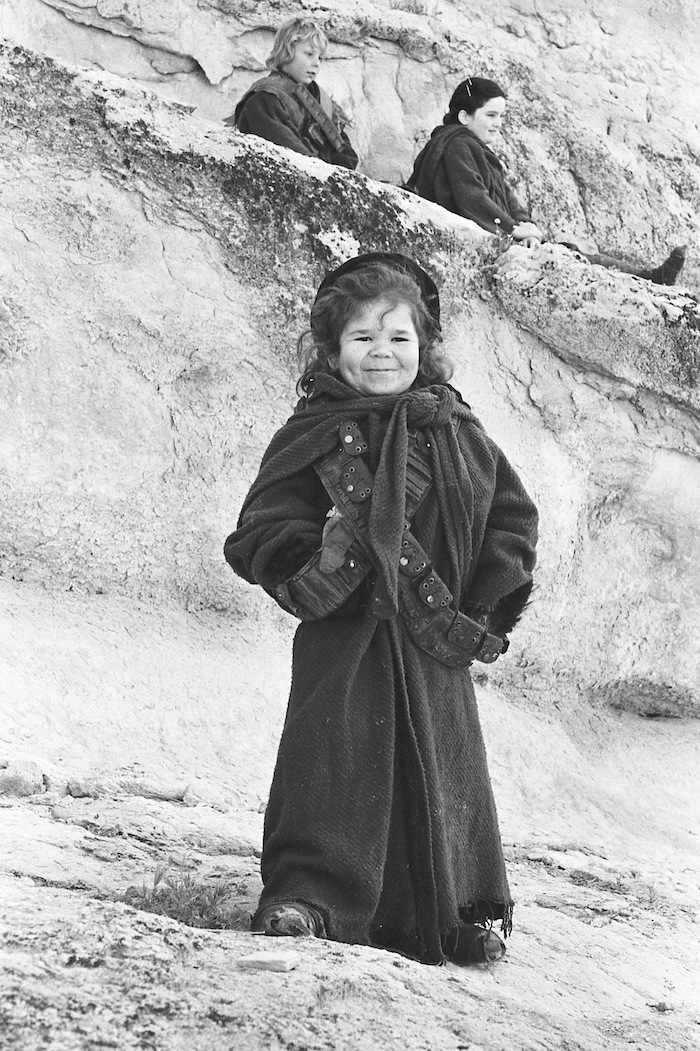

Head Jawa Jack Purvis (middle) talks with child Jawas.

“So we all stood around for a few minutes looking at each other and saying, ‘Wait a second. The script says the robot is rolling along and the head blows off. Now, you guys are supposed to know better than this. You’re the ones that designed this stuff.’ But we knew that nobody had had enough time to get ready,” he adds, “so we accepted all the problems on location. We had rushed and rushed to get ready for Tunisia, and I even considered postponing for two weeks, but we would’ve gotten into hotter weather, and that would have been a real disaster. So we went ahead with it.

“We ended up taking the fiberglass backup robot, putting it on a piano wire, and putting the exploding head on that. Les Dilley ran off and repainted it to match the red one.”

“There were all kinds of robots careening over the desert,” says Kenny Baker, who was inside R2. “They were all charging around on the flat desert. Jack Purvis was yelling, ‘Look out! There’s a robot coming!’ and it just crashed into me, tipped me over.”

Though this was surely not the best way to start the shoot, Lucas’s demeanor had an effect on at least some of the crew. “He’s always calm. Even if he has a storm going on inside of him, he’s very calm and soothing,” Hamill says. “Amazing things would go wrong technically. He’d be working with four robots in one shot and one’s radio-controlled, one’s hydraulic air-powered, one has a midget inside, and another’s on strings like a big marionette. If two of them hit the mark, it’s a print. I was amazed, because George moved really fast. I never felt he was really slighting the film, though. I’m sure there was a certain amount of compromise, but we moved really fast.”

“George is very good at compromising,” Barry agrees. “When Artoo falls off the ramp or something, he doesn’t mind because he knows he’s going to not use the shot at that point; he’ll cut away to something else. He’s prepared to ride the punches, as it were.”

By the time the unit wrapped on the first day, though the first of 355 scenes had been shot, they had failed to capture Luke and the “twin suns” because the Tunisian weather hadn’t cooperated. As for Daniels, who had started out relaxed, he was suffering terribly. “At the end of the first day, I was covered in scars and scratches,” he says. “I was very, very tired and very cross. That was the last time I ever wore the costume all day.”

UNIT DISMISSED: 19.20; SCS COMPLETED TODAY: 1; SCREEN TIME TAKEN TODAY: 2M 43S.

With “Red” on a piano wire, the robot was made to explode on cue after some frantic scrambling.

Scene B29, in which Luke looks for the little robot who has fled, was shot at the end of Day One.

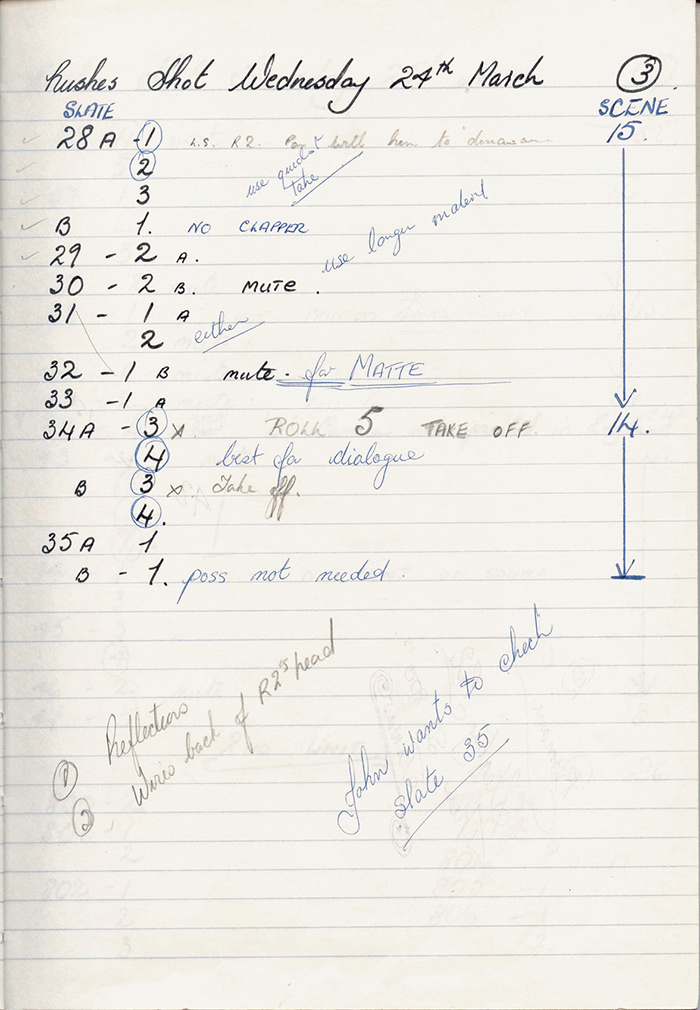

Within the “Rushes Book,” adorned with the logo created by McQuarrie, meticulous handwritten notes were kept for each slate for each scene.

REPORT NOS. 2–4: TUESDAY, MARCH 23–THURSDAY, MARCH 25, 1976 CALL: 06.30; SALT FLATS AND SAND DUNES AT NEFTA; SETS: EXT. LARS’ HOMESTEAD; EXT. EDGE OF DUNE SEA; EXT. DESERT WASTELAND; EXT. SANDCRAWLER; SCS: 26; 15 [C-3PO AND BLEACHED BONES]; 14 [C-3PO AND R2-D2 ARGUE ABOUT WHICH WAY TO GO]; B32 [STORMTROOPERS FIND EVIDENCE OF DROIDS]; C42 [LUKE DISCOVERS DEAD UNCLE OWEN AND AUNT BERU]; 3 PART [LUKE IN WASTELAND WITH DROID THAT MALFUNCTIONS]

At the end of the second day they again failed to get the sunset shot, as clouds unloaded “torrents” of rain on the desert, and the trucks carrying equipment got stuck in the mud. On the morning of the third day location auditor Ralph Leo left with the first day’s rushes, so John Jympson could start editing back in England, and Daniels’s difficult life in his metal prison continued during scene 15.

“If you look carefully when I’m walking past the big bones in the desert, you’ll see that I can barely move,” he says. “In fact, just as I got ’round the corner, I fell over. I was found with my arm sticking in the sand at ninety degrees, because, once I fell down, I couldn’t retrieve myself. And if nobody stood in my immediate range of vision, I was totally alone on that sand dune. My hearing wasn’t good, either, so I would spend many hours in my own little world unable to join in and chat with people. In the evenings I would seek out the biggest group of people making the most noise to relocate myself as a human being.”

That afternoon, Sir Alec and Lady Guinness arrived in Tozeur, but weather conditions continued to worsen, forcing Lucas to halt shooting at 5:57 PM due to “bad light.”

By the fourth day, despite the several setbacks, cast and crew were becoming familiar with their surroundings and one another. The location caterers, working in the mobile kitchen, managed to produce steak-and-kidney pie, while Mark Hamill and Gary Kurtz had discovered a mutual love of Carl Barks’s Donald Duck comics.

Daniels had to be pulled out of the sand after he’d waved on camera and then walked off camera behind a sand dune and fallen over.

The bleached bones were first assembled and approved in England before being shipped to Tunisia.

“We worked like stink, twenty hours every day,” Robert Watts says. “It was a very good shakedown period for a crew. To really get together out on location, and do it up front before you get to the studio, is good— to eat out of each other’s pockets, particularly in a small town like Tozeur.”

Because the production stayed in that one town for a few days, word went around that they were sometimes hiring, and Watts ended up employing a local youngster. “When I’d leave in the morning and every night when I’d come back, this kid is standing outside the hotel. So I’m not going to give him a job, because the minute I do, all his buddies will ask me for jobs. In the end, though, I decided I needed an office boy. He worked out very well because he worked very hard.”

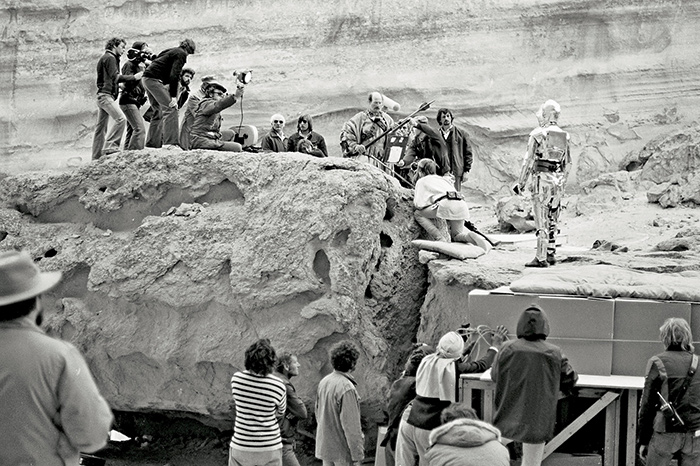

But in order to make up for the time they were losing, production had to split into two units. The second unit covered “Jawa activity shots with robots in front of sandcrawler,” while the first unit shot scene B32 with stormtroopers, played by “six local men” who were paid 8,500 dinars for the day ($6.50). The delays necessitating two units were partly due to unusually bad weather, but also to the earlier, unnatural holdups caused by the studio.

“It was purely a case of Fox not putting up the money until it was too late,” Lucas says. “Every day we would lose an hour or so due to those robots, and we wouldn’t have lost that time if we’d had another six weeks to finish them and test them and have them working before we started. Whereas before there were only about five or six people involved in the special effects, once we were on location with 150 people involved, we were paying much more in salaries—so that six-week delay cost an enormous amount of money. Ultimately, we had to scrap whole days out there in Tunisia and say, ‘Okay, we’ll try to pick that up when we get back to the United States.’ ”

Another robot crisis occurred when the truck carrying several of them caught fire, and two robots slated for the homestead set were damaged.

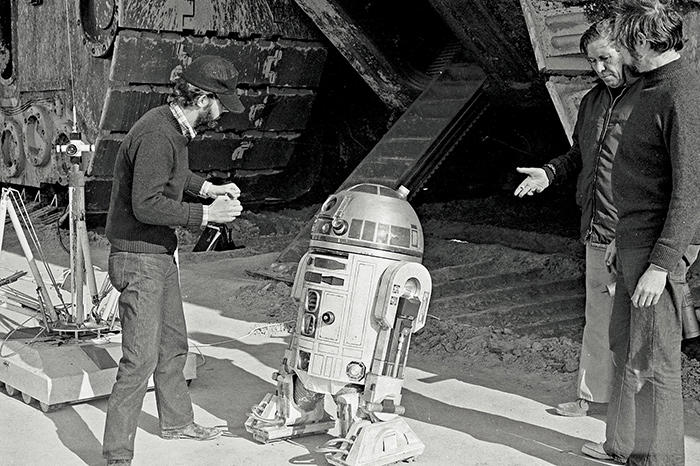

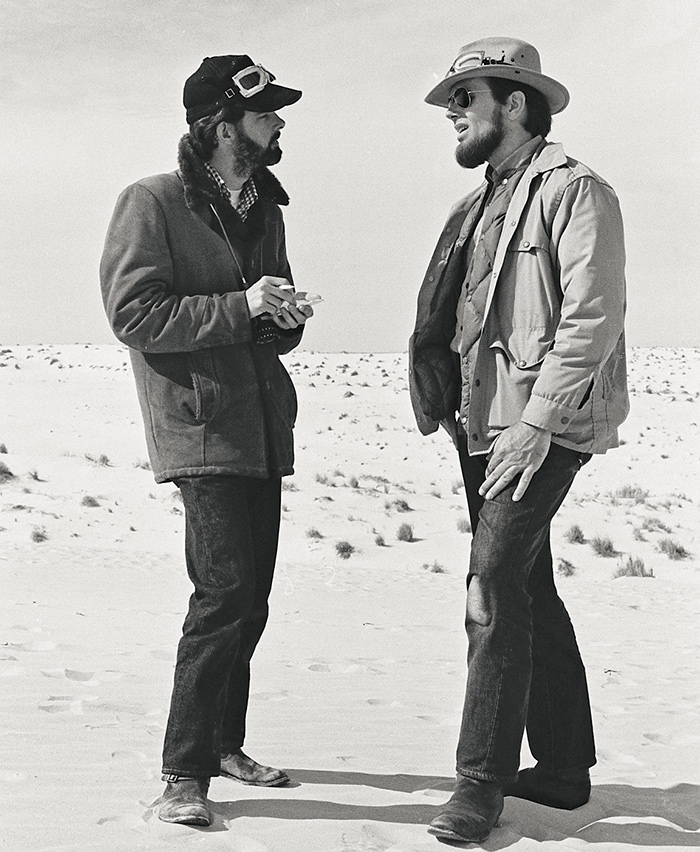

Lucas directs the stormtroopers.

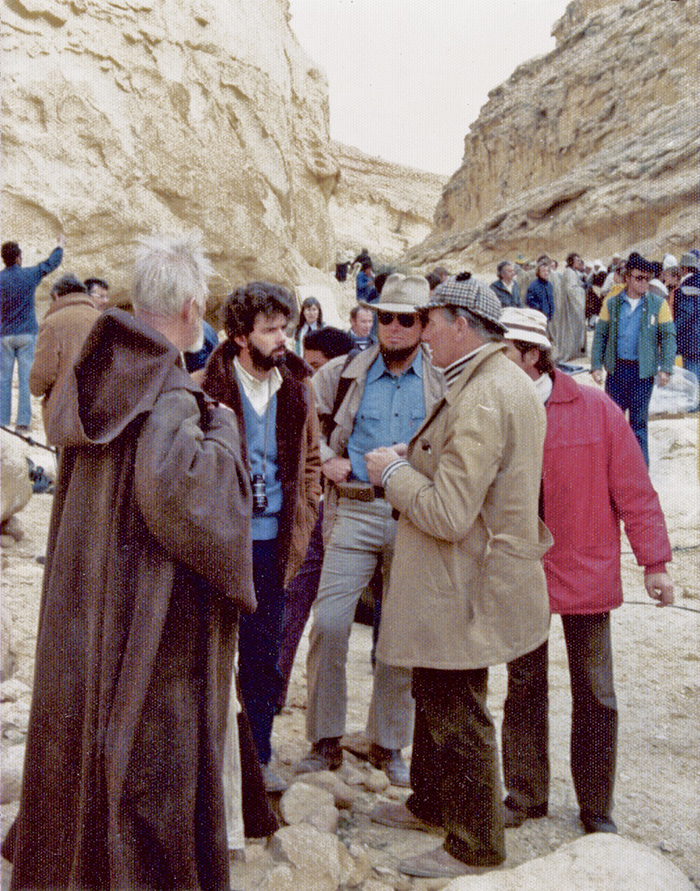

Lucas talks things over with Kurtz.

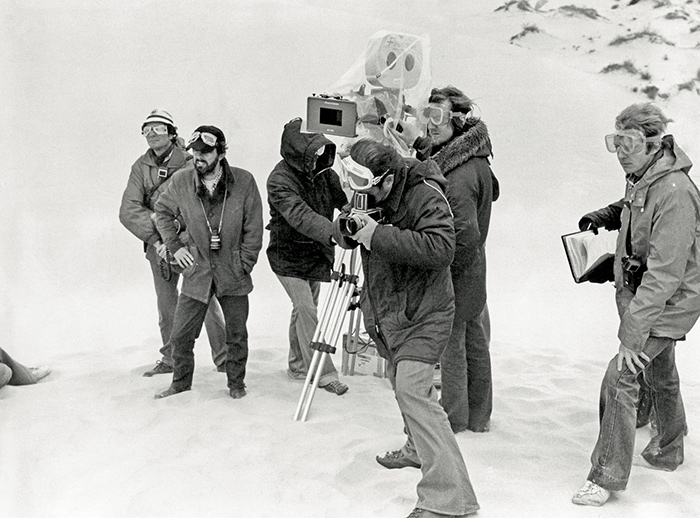

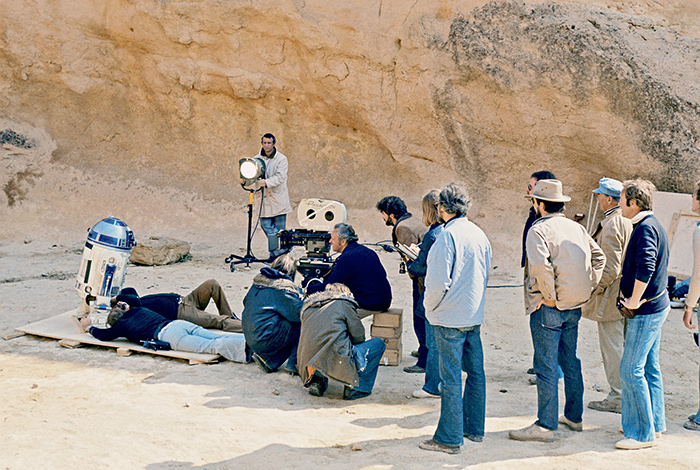

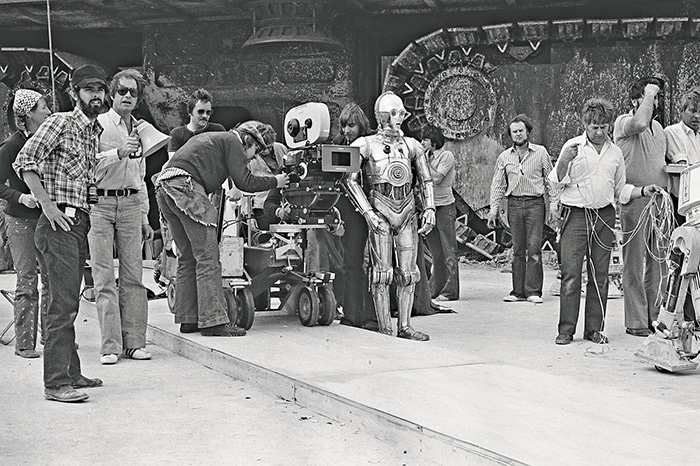

Lucas sets up the shot with his camera crew.

His camera crew films the six stormtroopers.

The six stormtroopers afterward pose for a group shot following their work’s completion.

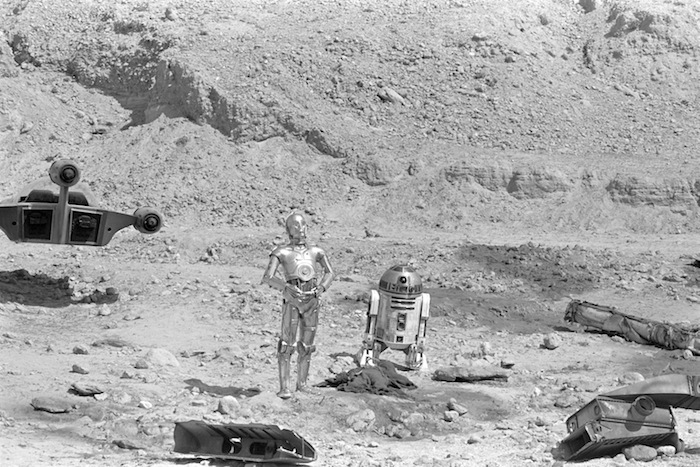

Black-and-white photography taken on location.

“We had a black all-in-one leotard for the stormtrooper costume,” Mollo says, “over which the front and back of the body went together; the shoulders fit onto the body, the arms were slid on—the top arm and the bottom arm were attached with black elastic—a belt around the waist had suspender things that the legs were attached to. They wore ordinary domestic rubber gloves, with a bit of latex shoved on the front; the boots were ordinary spring-sided black boots painted white with shoe dye. Strange to say, it all worked.”

SCS COMP: 5; TIME TAKEN: 6M 46S; DAILY STATUS: 3/4 DAY OVER

REPORT NOS. 5–7: FRIDAY, MARCH 26–SUNDAY, MARCH 28, 1976 CANYON IN TOZEUR; SETS: EXT. ROCK CANYON; SCS: 37 [LUKE AND C-3PO FIND THE FUGITIVE R2-D2]; 38 PART (SOME OF THIS TO BE SHOT IN USA) [LUKE ATTACKED BY TUSKEN RAIDER]; 39 PART [ARRIVAL OF BEN KENOBI IN CANYON]; 40 [LUKE FINDS INJURED C-3PO]

Problems with the landspeeder also played a part in the decision to do pickups in the United States. The scene with the banthas, however, which were to be portrayed by elephants, had always been scheduled for later. “By the time we would have dragged out two circus elephants and fought with them and waited around endlessly with the crew, entailing all those associated costs, it was clear that it was not a practical idea,” Barry says.

Despite slow going, the one scene completed on Day Five—in which Luke finds an errant R2-D2—helped Hamill better understand his character. “George is Luke,” Hamill says. “He is. I always felt that way. We were in the desert one time—it was the scene where I had just found Artoo after he ran away—so I ran up and said, ‘Hey, where do you think you’re going?!’ And to Threepio, ‘Do you think I should replace the restraining bolt?!?’ But George came up to me and said, ‘It’s not a big deal.’ He acted it out, just walking up and saying, ‘Noo, I don’t think he’s going to try anything.’ At that point, I was thinking, Well, he’s doing it so small, so I’ll do it just like him—and he’ll see how wrong he is. So I did it like that—and he said, ‘Cut. Print it. Perfect.’ So I thought, Oh … I see.

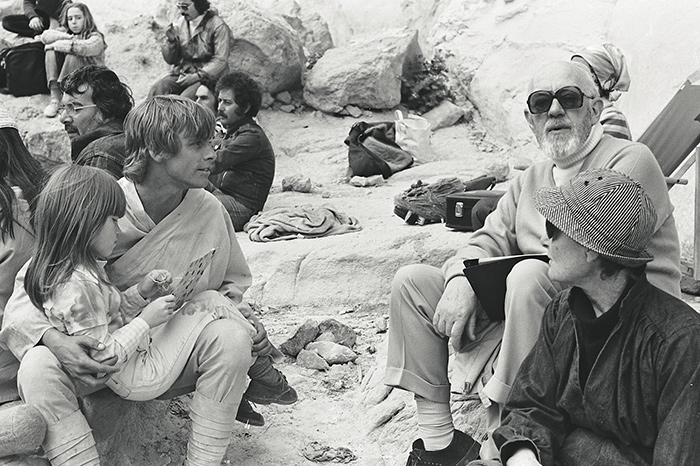

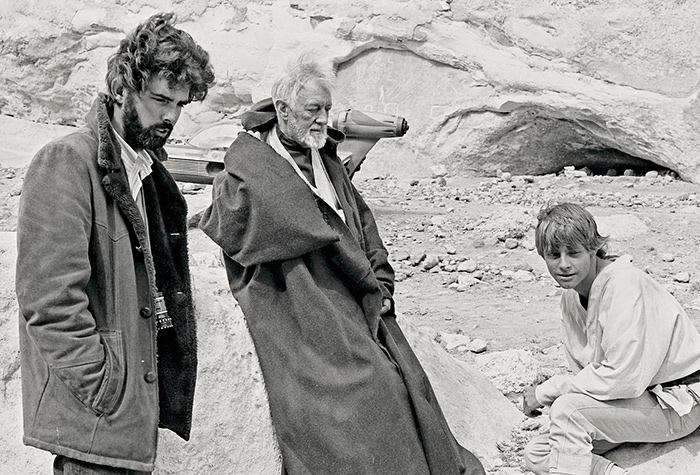

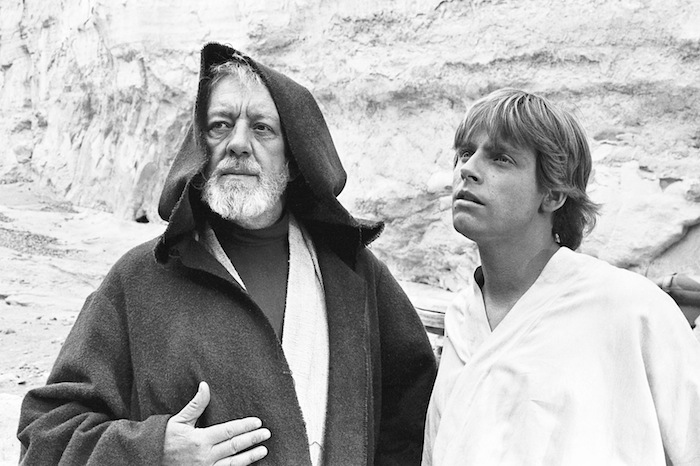

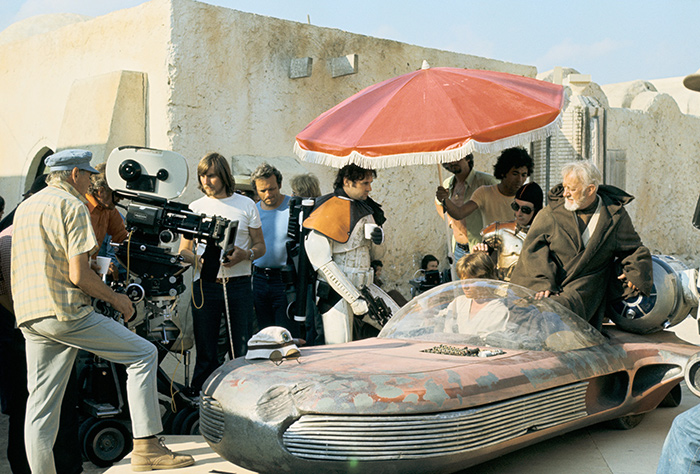

Sir Alec and Lady Guinness are greeted upon their arrival by Lucas.

Sir Alec and Lady Guinness chat with Mark Hamill.

Lucas confers with his DP, Gil Taylor.

They shoot Luke looking into the skies while tending to a moisture vaporator. “Luke’s poncho was just a straight blanket with some edging to it,” Mollo says. “There were all sorts of funny sombreros and hats, but eventually we abandoned the hat for Luke.” In total, five outfits were made for Luke at a budget of £2,020 ($4,700). “The moisture collectors were made out of airplane junk,” John Barry says, “but somehow they look believable.”

On location in Tunisia, late March 1976, John Stears radio-controls a droid, while

Mark Hamill is filmed watching the skies. (No audio)

(0:46)

When Luke (jumping out of his land-speeder perched on its carousel arm, left) finds his dead aunt and uncle, Hamill thought it would be appropriate for his character to fall on his knees sobbing, but Lucas preferred a more neutral performance, so that audiences would be able to project their feelings onto him. Lucas knew that later on he would edit the sequence in keeping with the art of montage as explained by early Russian filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov, in which the juxtaposition of shots would arouse emotion, rather than just the actor’s performance.

Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) arrives to find his home in flames and his family murdered.

Mules once again were used to help carry equipment to remote areas, such as the spot where they filmed the arrival of Ben Kenobi; while Lucas conferred with his crew, however, delays with the little robot persisted.

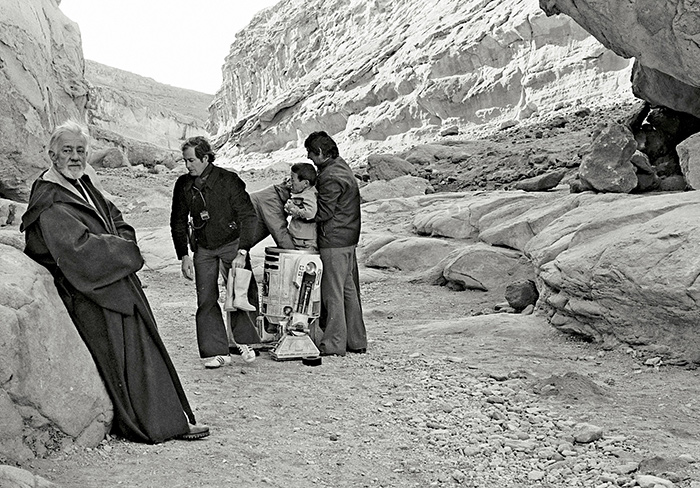

Sir Alec Guinness clowns around with Kenny Baker and then films the scene in which

Ben and Luke discover a damaged C-3PO (note that only the droid’s torso would be in

the shot, so his pants are “off”). (No audio)

(0:42)

“After that, I often felt like I was playing George; I even went so far as to do his little beard gestures,” Hamill adds. “George even gave me his nickname, The Kid; they used to call George The Kid until he grew his beard.”

Daniels was also getting into character. “See-Threepio is a kind of English butler, a cross between Laurel and Hardy with his friend,” he says. “He loves being around Luke because that’s his purpose—to look after people—he wants to make them happy. I think that’s one reason why the part works. This unlikely shape has all the human attributes and possibly more, though it seems outlandish, because he isn’t human. The odd thing was I kept acting the whole thing out, facially, if I were emotionally upset in a scene or angry, even though no one could see me.”

Friday’s shooting again wrapped early due to heavy rains—and on Saturday the bad weather reached its peak, developing into a terrific storm. “We get up in the morning, and though we are supposed to be in the sun-drenched southern part of Tozeur, it is pissing rain and there’s a wind like you wouldn’t believe,” Watts says. “So I call a rest day, and I go down to Les Dilley and take him out to the salt flats. We drove out in the Land Rover all right—but when we got out of the car, it was so slippery we couldn’t even stand up. Luckily the local security guards had these Wellington boots, with the heavy treads on the bottom. We had one each supporting us, so we could get out to see the damage to the sets. The top had gone off the homestead and that was already halfway to Algeria somewhere.”

“It had blown away,” Barry says. “It blew three miles in the night, it just rolled and rolled and rolled.”

“The sandcrawler had been completely blown apart!” Lucas recalls. “Stuff had gotten stuck in the mud. Then the army trucks that came to pull the stuff out of the mud got stuck in the mud—and stayed there until the weather changed.”

The crew regrouped and rebuilt, however, and on Sunday, Guinness appeared for the first time in costume as Ben Kenobi. “What I remember about Sir Alec Guinness was that, before going on camera, he lay down in the sand in his brand-new clean costume and dirtified himself,” Bunny Alsup says. “I thought this was unique and wonderful. Only later did I realize that George probably asked everybody to do this because one of his goals on the film was for everything to be used and dirty.”

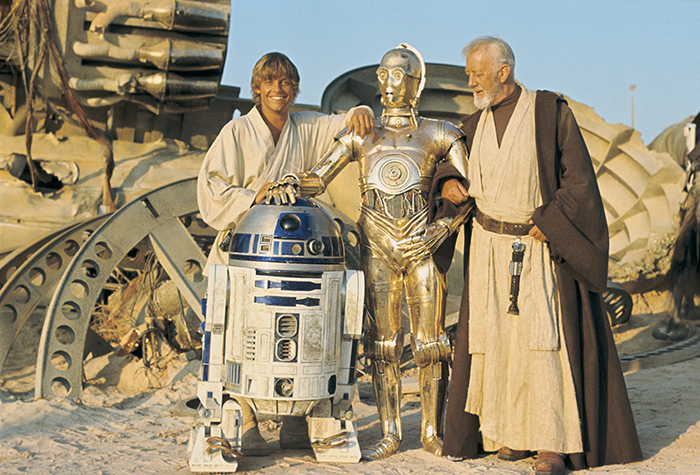

Having arrived several days earlier, Guinness was playing the scene in which he finds Luke in the canyon after the Tusken Raiders have attacked. “We worked about a week without him, but we’d see him,” Hamill says. “I think Tony Daniels and I had dinner with him and his wife, Lady Guinness, twice.”

As they quickly filmed the canyon setups, Hamill adjusted to working with the vastly experienced older actor. “At first, I felt very much like you do when you go before the principal, but then I thought I should be more myself, because that’s what he’s like. So we loosened up to the point where I could just sit next to him and not say anything for an hour while they were setting up. I know he really liked that. He felt that we were taking each other into our confidences. Two or three times, he would say, ‘May I suggest something?’ And, gosh, I wish he would do that all the time, because he was always right. He would say, ‘Stop and think of what you’re saying. Are you talking about going or are you going there?’ Because it’s not the fact that I’m going but where I’m going. Little things like that. You’d think about it, and, usually after you’d shot it and were on your way home in the car, you’d understand what he meant.”

Lucas, Guinness, and Hamill watch and wait before filming Obi-Wan’s first scene.

“We did work in Tunisia on these extraordinary salt flats,” says Guinness, who was enjoying himself. “There’s a great feeling of strange space that stretches on for hundreds of miles; it’s genuine, real and gritty—it’s not some made-up world.”

SCS COMP: 7; TIME TAKEN: 11M 0S.

REPORT NOS. 8–10: MONDAY, MARCH 29–WEDNESDAY, MARCH 31, 1976

TOZEUR; ROCK CANYON; SCS: 38 [TUSKEN ATTACKS LUKE]; 47 [VIEW OF MOS EISLEY, “SCUM AND VILLAINY”]; 35 [TUSKEN RAIDERS ESPY LUKE IN LANDSPEEDER]; 17 [JAWAS NEUTRALIZE R2-D2]; 18 [JAWAS CARRY R2-D2 TO SANDCRAWLER]; B42 [LUKE AND BEN DISCOVER DEAD JAWAS]; E42 [JAWA BONFIRE]

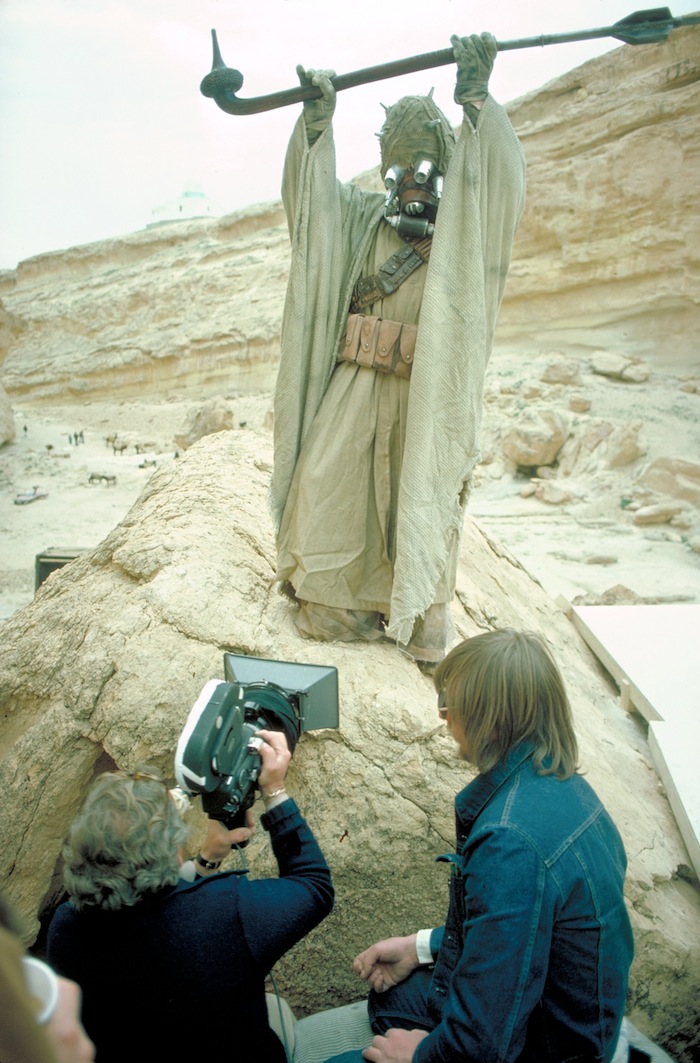

By Monday, on a logistically complex day, with first and second units working on the salt flats and in the canyon near Tozeur, several scenes were completed: Obi-Wan’s arrival; Luke watching the battle in space; and stunt supervisor Peter Diamond playing the Tusken Raider who attacks Luke. The veteran stuntman and actor rehearsed without costumes—but when the cameras rolled and Diamond donned the Tusken headgear, he realized he couldn’t see. As Hamill dodged the blind stuntman’s violent blows, his look of fear was real.

The rest of that day was spent climbing up to the cliff from where they’d command a breathtaking view of the canyon below, which would later be replaced by a matte painting of Mos Eisley. The crew gathered their equipment for the trek—including an indispensable (for the English) tea urn—and packed up the mules and porters. When they got to the top, Daniels was put into his metal outfit just in time for tea and, to his annoyance, had to wait inside his prison for the duration of the break.

At the end of that day, the shot that bad weather had foiled three or four times before—scene 29: Luke and the twin suns—was attempted once more. With the clouds dissipated, they set up the VistaVision camera, waited, and got it.

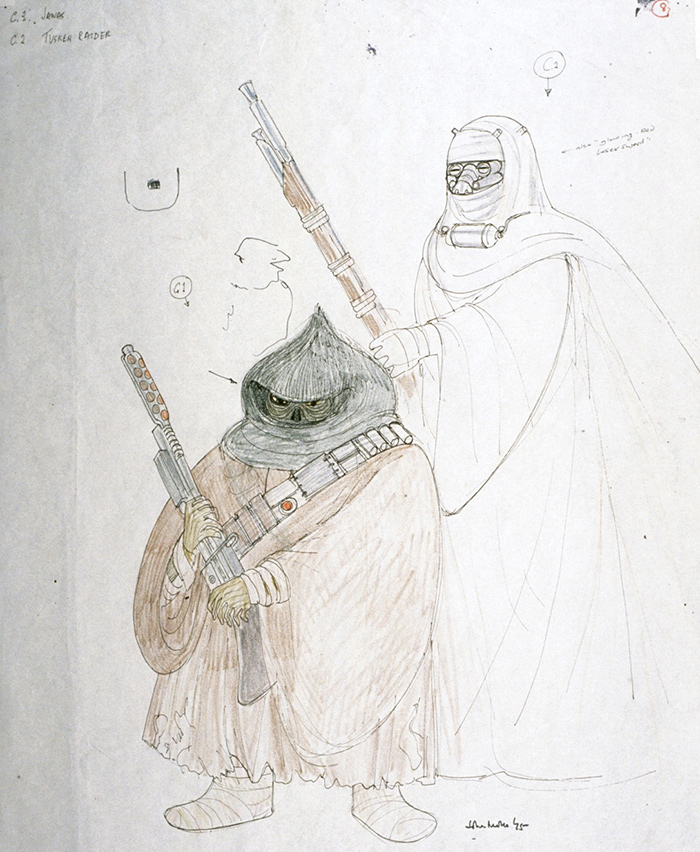

By Tuesday, Day Nine, production was concentrated in the rock canyon during what was another day of fairly intense filming for the Jawas. Playing those diminutive creatures were Kenny Baker’s cabaret partner, Jack Purvis; Gary Kurtz’s two children; the son of an English truck driver; Mahjoub, a little Tunisian who usually worked for the hotel in Tunis; and local children aged eight to ten. “The Jawas had to be designed from scratch,” John Mollo says. “They were supposed to look like little rats, sort of grimy and filthy. George produced a prototype, which he subsequently felt was too theatrical, so we pulled it back to just a black stocking mask and these eye-bulbs, which were wired on, a little brown cloak with a Russian Cossack hood, and a scarf. Then we’d put other bits and pieces on them the day of shooting just to make them look a bit more formidable.”

For the shot in which Daniels had to drop a Jawa cadaver into a bonfire, the body was placed onto his already outstretched arms; fighting his limited visibility, he then tried to coordinate his movement with Luke’s, as his landspeeder was swung around by the carousel. Hidden beneath his armor, Daniels was also able to quietly analyze his relationships with fellow actors: “Without being unloyal to Kenny Baker,” Daniels says, “he didn’t read the script from beginning to end, so I was totally on my own. In fact, it was very difficult because I would say something to him and there would be absolute silence. Often it was very lonely doing scenes with him, for he wasn’t there. As for Mark, I used to kid him that even when I wasn’t speaking in our scenes together, nobody was going to look at him because I was gleaming and shining in all the lights, nodding and upstaging him generally—but one of the things that is a delight is the way Luke talks to See-Threepio. The same with Alec Guinness, though he must have had a very difficult time in his career to suddenly start acting with robot scrap heaps.”

Alec Guinness as Ben Kenobi chases off the Tusken Raiders and revives Luke, who lies next to his landspeeder (its supporting post is concealed by a rock, below).

Peter Diamond, without mask, rehearses with Hamill and crew the scene in which a Sand Person attacks Luke with a formidable weapon, because Diamond would be literally blind when the cameras rolled and he was aiming blows at the actor (mattresses were placed to cushion their falls—and Daniels wears shoes because his feet are not on camera).

Hamill inspects the weapon with some trepidation.

On Monday, March 29, Mark Hamill prepares and then plays the scene in which his character reflects on his dreams. The second sun would be added in post-production.

“I found him to not be an easy guy to get close to,” Baker says of Daniels. “We didn’t argue or anything, but we were not close friends.”

Daniels also overheard a brief difference of opinion between Taylor and Kurtz, as they hurried to catch the fading light for a shot of the Jawas loading R2 into the sandcrawler. “I didn’t grasp them all but, ‘Who’s meant … be lighting this … movie,…or me, because … you’re … it, I’ll … off!” Daniels says.

By the second week of location shooting, the radio-controlled robot problems had formed a frustrating pattern: “In the morning we had perfect reception,” John Stears says. “But by two o’clock we had all sorts of problems with interference.” They would pick up other radio stations, which Stears hypothesized may have been due to mica buildups under the sand. Some problems were resolved by playing around with the aerials, but as the days wore on new difficulties arose.

“We got some weird signals from Arabic radio stations,” Hamill says. “It was really frustrating. We’d get things almost all ready—and the robots would go bananas, bumping into each other, falling down, breaking. It took hours to get them set up again.”

Also by this time, several questions that had been developing in relation to the script had been posed—and a solution found. The problems were essentially two: Ben Kenobi didn’t really have anything to do in the film following his escape from the Death Star; and the Death Star, theoretically a very dangerous place, was too easy to escape from. In short, the film needed more drama. The answer to both structural problems was to kill off the Jedi Knight. At one point C-3PO and Chewbacca were also candidates for death, but Ben was the most logical choice—as it also enabled Lucas to make an important point about death and its relation to the Force. Kenobi wouldn’t just die, he would disappear, joining the Force with his consciousness intact.

“I started writing the revised fourth draft while we were in London doing preproduction,” Lucas says. “I continued it when I was in Tunisia and I didn’t finish it till we were back in England. I had been toying with the idea of killing Obi-wan but I made the decision while we were in the desert. I was struggling with the problem that I had this climactic scene that had no climax about two-thirds of the way through the film. I had another problem in the fact that there was no real threat in the Death Star. The villains were like tenpins; they just got knocked over. As I originally wrote it, Ben Kenobi and Vader have a swordfight, and Ben hits a switch and the door slams closed and they all run away, and Vader is left standing there with egg on his face. They run into the Death Star, take over everything, and run back. It totally diminished any impact the Death Star had.”

As a late entry into the story, Kenobi hadn’t always fit in. Even the first appearance of the old man in the synopsis, where he is essentially a vehicle for the film’s spirituality, had obliged Lucas to search for plot points that would involve him. Rewrites are common during shooting, however, so Bunny Alsup was already armed and ready for script changes. “I had shipped my IBM typewriter with all of the other equipment,” she says. “But the typewriter fell off the plane while they were unloading in Tunisia and was broken. That was pretty tough. But we had production secretaries there, and one was French and she had a French manual typewriter, not even electric. Using that was exceedingly difficult because some of the letters are in different places. Then I got sick on some fish and had dysentery. I was so sick, sick as a dog, but I couldn’t afford to be sick because I had to type the pages—and I managed to get that done with a French [laughs] typewriter.”

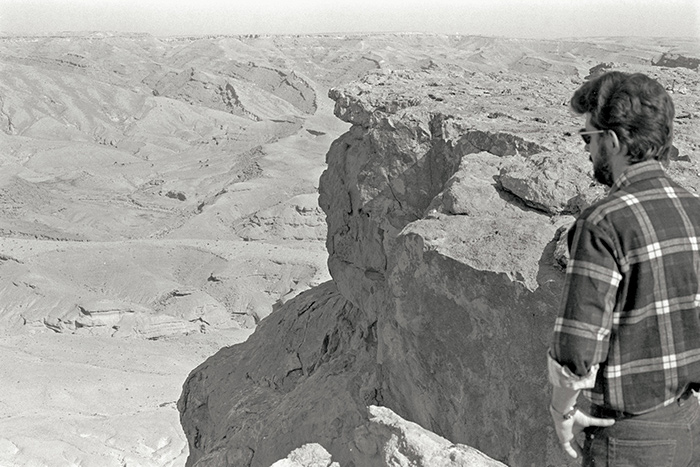

Lucas

Hamill as Luke

In Tunisia, Hamill, who had realized that Luke and Lucas were one and the same (as two photos of Lucas and Hamill overlooking the desert say, visually), climbed with Guinness and company to the top of a mountain for the scene in which they see Mos Eisley for the first time. Below them was the large sandcrawler set, which cost £54,850 ($128,000), and which caused some strange reactions–or not so strange, when you recall that its tread systems were based on NASA-designed vehicles. Because it was placed on the Tunisia-Algeria border, and because Tunisian military trucks were being used by production, the Algerian government registered official concern about what they perceived as a massive military mobilization on their border. “It’s true about the border,” Lucas says. “They had to come and inspect the sandcrawler to verify that it was not a secret weapon.” The sandcrawler had been transported in pieces from its salt flats location to its rock canyon location–a move complicated by the fact that it had been blown apart earlier by the storm.

A printed daily of scene 47, above Mos Eisley, on location, circa the end of March

1976.

(0:22)

“I took Alec aside and told him I was going to kill him off halfway through the picture,” Lucas recalls. “It is quite a shock to an actor when you say, ‘I know you have a big part and you are going to the end and be a hero and everything and, all of a sudden, I have decided to kill you.’ Alec was a very, very brilliant man but he was also an actor and very emotional, very human. ‘You mean I get killed but I don’t have a death scene?’ he said. But he kept it under control.”

Lucas explains a shot to Gil Taylor.

Hamill as Luke is then filmed looking into the pit/set where the crew would also lunch.

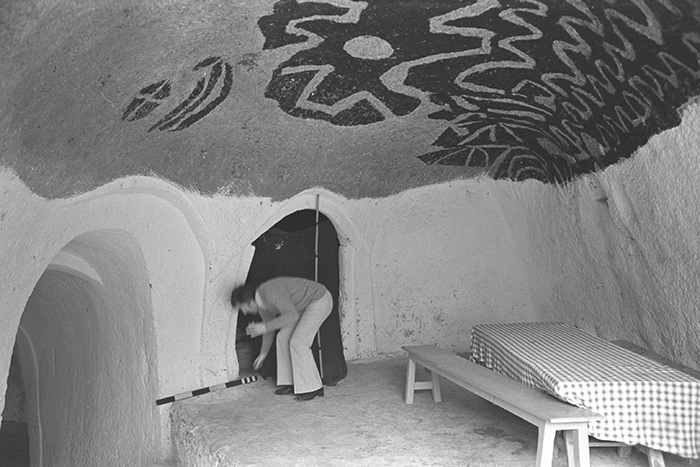

In one of the Hotel Sidi Driss alcoves, Phil Brown and Shelagh Fraser (Aunt Beru) were filmed with Hamill.

The Lars homestead courtyard set was budgeted at £6,200 ($14,500).

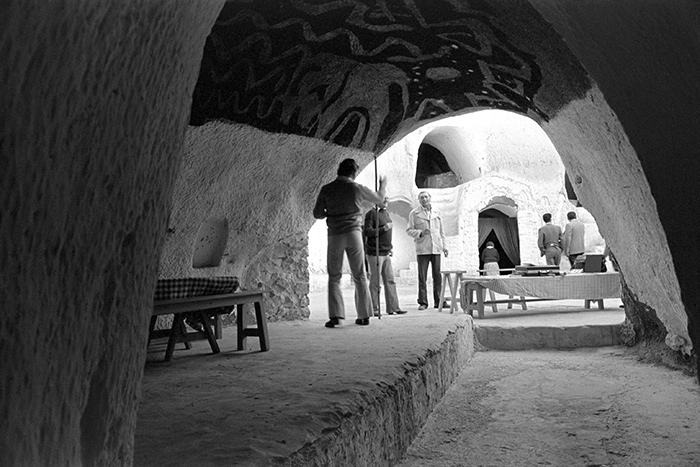

In the Hotel Sidi Driss in Matmata, Tunisia, cast and crew eat lunch where scenes

would also be shot of the interior homestead, early April 1976. (No audio)

(0:31)

On April 2, 1976, Hamill, Kurtz, and Lucas toasted Guinness on the occasion of his birthday, in Djerba. In the background, a “crashed” spaceship masks a tree.

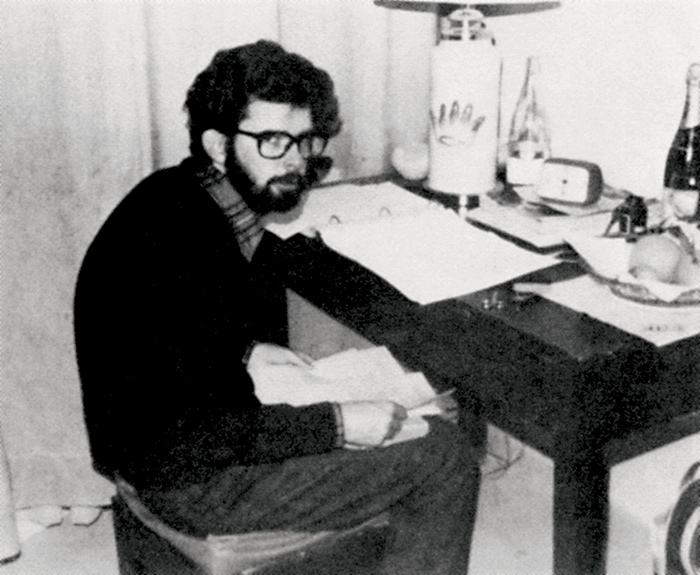

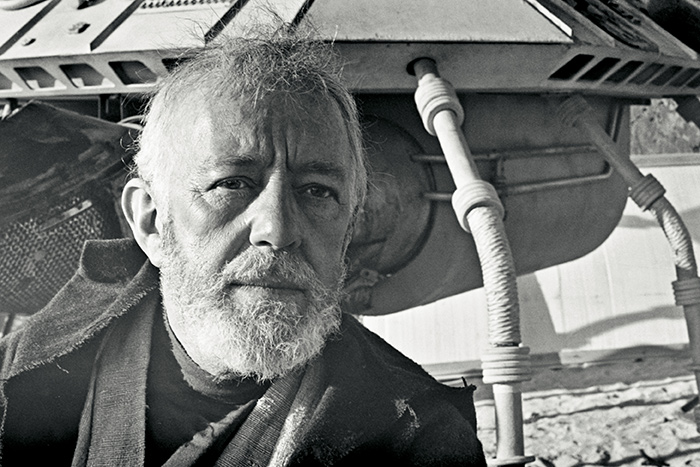

The expression of Lucas, sitting in his hotel room in Tunisia, reveals the stress the ongoing multiple problems were causing the director on location.

Under control, for the meantime.

SCS COMP: 15; SCREEN TIME: 15M 48S.

REPORT NOS. 11–14: THURSDAY, APRIL 1–SUNDAY, APRIL 4, 1976

HOTEL SIDI DRISS, MATMATA (GABES LOC.); SCS: 26 [PURCHASE OF C-3PO AND R2-D2]; A28A (EXTRA); 32 [OWEN LOOKING FOR LUKE AT HOMESTEAD]; A28 [LARS’ HOMESTEAD—DINING ROOM]

AJIM, DJERBA; SCS: 48 [BEN: “THESE ARE NOT THE DROIDS YOU’re LOOKING FOR”]; 59 [MOS EISLEY: STORMTROOPERS WATCH MILLENNIUM FALCON FLY OFF]; ZA50 (EXTRA) [C-3PO IN FRONT OF CANTINA]; A50 [BEN TELLS LUKE HE’ll HAVE TO SELL HIS SPEEDER]; 49 [IN LUKE’s SPEEDER, THEY APPROACH CANTINA]

MOSQUE, DJERBA; SCS: 8 [LUKE IN LANDSPEEDER ALMOST RUNS DOWN A WOMAN]; 10 [BIGGS AND LUKE WATCH BATTLE IN SPACE ON TATOOINE]; 16 [BIGGS TELLS LUKE HE’s GOING TO JOIN THE REBELLION]

The morning of April 1, production moved several hours by car to the homestead location in Matmata, located within the Sidi Driss Hotel. There, Shelagh Fraser (Aunt Beru) joined the crew for the first time. Again, Lucas’s notes contain his thoughts on casting: “a little British, but okay.”

The sunken hotel courtyard had been transformed into the homestead hole by Barry and his crew, with ingenious dressing that included two storage tanks, toys, kitchen units from an aircraft galley, drainpipes, and yards of specially made material. Cast and crew stayed here only one day, however, before moving on to Djerba.

Shoot Day Twelve was the first in the “Old West” town of Mos Eisley. To populate the one-horse outback, production again used twelve children as Jawas; four men playing Tusken Raiders; six men as stormtroopers; four as starpilots; three as robots; and sixteen men and women as farmers. The town of Djerba had been modified by Barry, who had spotted it during one of his location-scouting trips.

“It looked very interesting with those strange low domes, which I saw just as I was going by on the way to the ferry one day,” he says. “You can just see them from the road. So we added to those domes; we created premade domes, and I put one on top of each box-like building. Then, because all the electrical supplies are aboveground on poles, we decided to mask them. I invented a strange aerial, which you can see sticking up all over the place, which we fixed to all the electrical supplies just to make them look like something else. Then there was one tree around which we built a big crashed spaceship. We had made a great big machine, a sort of roller, to make tracks across the desert for the sandcrawler—so we used that as dressing in the street. We never wasted a thing!”

Needless to say, the local population was “a bit amazed” by all these doings, and a guard was kept on location at all times. “They stood around and watched us shoot,” Kurtz says. “ ‘Those crazy Americans!’ ”

By Day Thirteen the C-3PO suit was literally starting to come undone. “There is one scene where you see me walking away from camera into the cantina behind Luke, and my trousers have completely given up,” Daniels says. “In fact, bits of me would fall apart. They would ask if I could play the scene with my arm bent. I would open my arm, and a greebly would fall off. Basically I was classed as a prop, so through the whole film I had an amazing prop man to look after me, Maxie, who had worked in Tunisia before. He would stand there shouting strange words in Arabic mixed with French to the Tunisian helpers, and they really liked him.”

The cantina exterior that Daniels stumbled toward was surrounded by many of the landspeeder prototypes, keeping to Barry’s maxim of zero wastage. Having finished the scenes in Mos Eisley, production packed up and moved to the mosque location.

For the last day of the Tunisian shoot, on April 4, Garrick Hagon (Biggs), Anthony Forrest (Fixer), and Koo Stark (Camie) arrived for their scenes with Hamill in Anchorhead. Scene 8 was a shot of a woman, played by a local, shaking her fist at Luke, who drives by too fast for her liking. In one of the odder happenings, Stark recalls that the Lucasfilm production did end up meeting the Zeffirelli production: “Operated by remote control, R2-D2 had to trundle off camera and disappear behind a sand dune,” she says. “But the remote control failed to stop the robot and he wandered onto the set of Jesus of Nazareth!”

Despite the quantity of work scheduled for the last day, they sped through it—much to the relief of all involved. Following crew wrap, Daniels and Hamill had dinner together. “We talked,” Daniels says. “We had enjoyed working together in this peculiar world.”

Having decided to be an actor at a very early age, Hamill noted that it had been amazing. To celebrate, they both then attended a cast-and-crew party paid for by Lucas and Kurtz—a brief respite from the twenty-hour days on location before months of work in London. Only cameraman Jeff Glover and his assistant, Mike Shackleton, would stay behind to shoot a couple of aerial plates for the landspeeder and a few pickup shots of R2-D2.

“We made it,” Robert Watts says. “We got out of Tunisia on schedule, which was important—because this picture has masses of problems. Electronic devices, radio-controlled robots, people wearing weird suits, strange sets—I mean, it’s stuff that hasn’t been done before. We were underscheduled in preparation time, and with the best luck in the world, you can’t predict everything that’s going to go wrong.”

While Watts remained upbeat, Lucas didn’t appear that evening, going to bed early, exhausted and disturbed. “By the end of the location shoot, I’d only got about two-thirds of what I’d set out to get,” he says. “It kept getting cut down because of all the drama and I didn’t think it’d turned out very well; I wasn’t happy with what I had managed to get. I was very depressed about the whole thing. I was so depressed I couldn’t even go to the wrap party. I just wanted to go to sleep. I was seriously, seriously depressed at that point. Because nothing had gone right. If things continued in that way, I was never going to get the movie finished. Everything was screwed up. I was compromising right and left just to get semi-things done. I was desperately unhappy.”

Christian describes having lunch on the road to Djerba, Tunisia, with a tired and

dejected Lucas. (Interview by Rinzler, 2012)

(1:39)

SCS COMP: 28; SCREEN TIME: 24M 39S.

Mollo’s sketch of the Jawa costume.

The finished costume on the day they filmed three Jawas in Djerba.

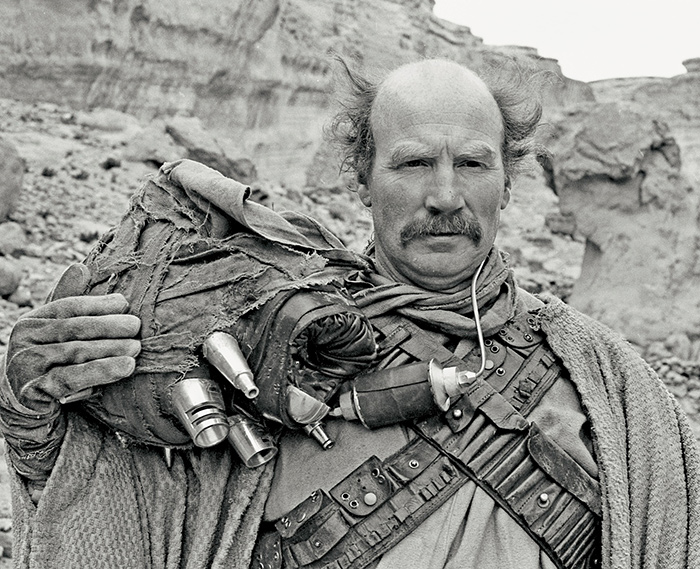

Jack Purvis played lead Jawa as well as several robots.

In Ajim, Djerba, an extra is lowered, strapped into a droid, and shown how to walk;

the heroes’ arrival in Mos Eisley is then shot with the droid acting as foreground

dressing; early April 1976. (No audio)

(1:20)

Djerba was first tagged as a possible location by Barry, who took several photographs during his recces.

Peter Diamond plays a farmer in Barry’s transformed Djerba.

Hamill, Daniels, and Guinness pose in front of the dressed cantina exterior.

Lucas survived Tunisia, but was unhappy with what had transpired there.

Alec Guinness in Djerba.

On April 4, 1976, the last day of the Tunisia shoot Koo Stark (Camie) and Garrick Hagon (Biggs) arrived for their scenes.

Lucas checks a shot, with the camera protected from the desert sand by a plastic sheet.

Hamill shoots scenes with Garrick Hagon (Biggs) and Koo Stark (Camie).