REPORT NOS. 15–17: WEDNESDAY, APRIL 7–FRIDAY, APRIL 9, 1976

CALL: 08.30; EMI STUDIOS, BOREHAMWOOD

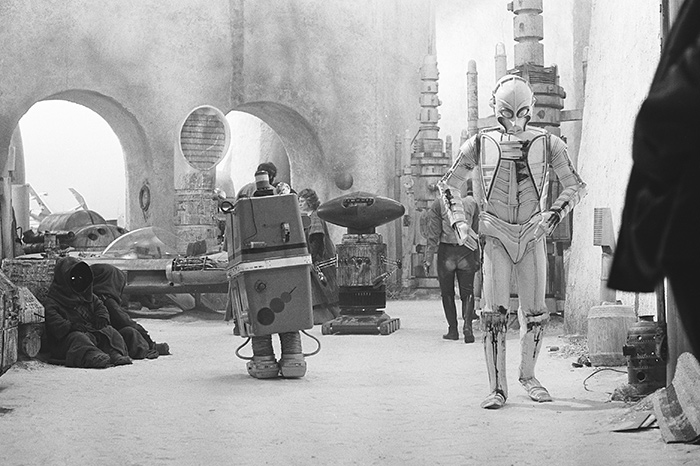

STAGE 7: INT. LARS’ KITCHEN; INT. ANCHORHEAD POWER STATION; 28 [BERU FILLS PITCHER WITH BLUE MILK]; A32 [OWEN LOOKING FOR LUKE, TALKS WITH BERU]; 9 [ANCHORHEAD: BIGGS/LUKE REUNION]

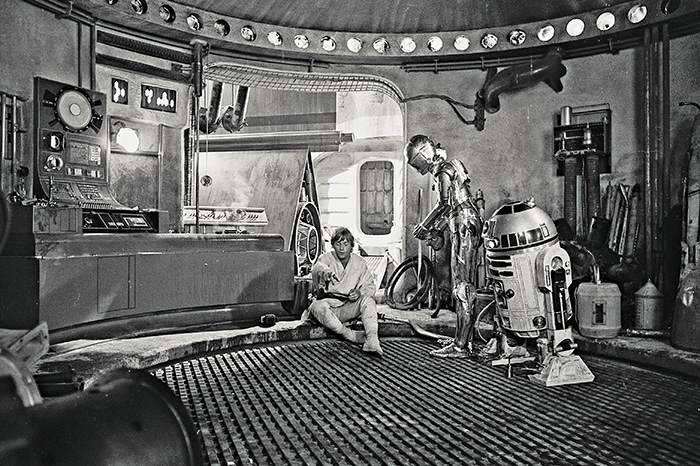

STAGE 1: INT. LARS’ HOMESTEAD (GARAGE); 27 [C-3PO TAKES OIL BATH AND LUKE DISCOVERS LEIA’s MESSAGE]; A29 [LUKE FINDS C-3PO HIDING IN GARAGE]

STAGE 3: INT. DOCKING BAY 94; AA53 PART [JABBA AND HAN SOLO]

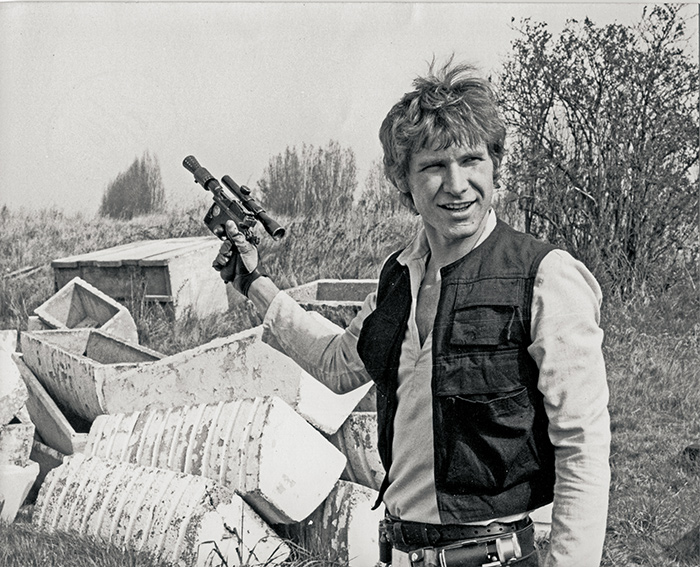

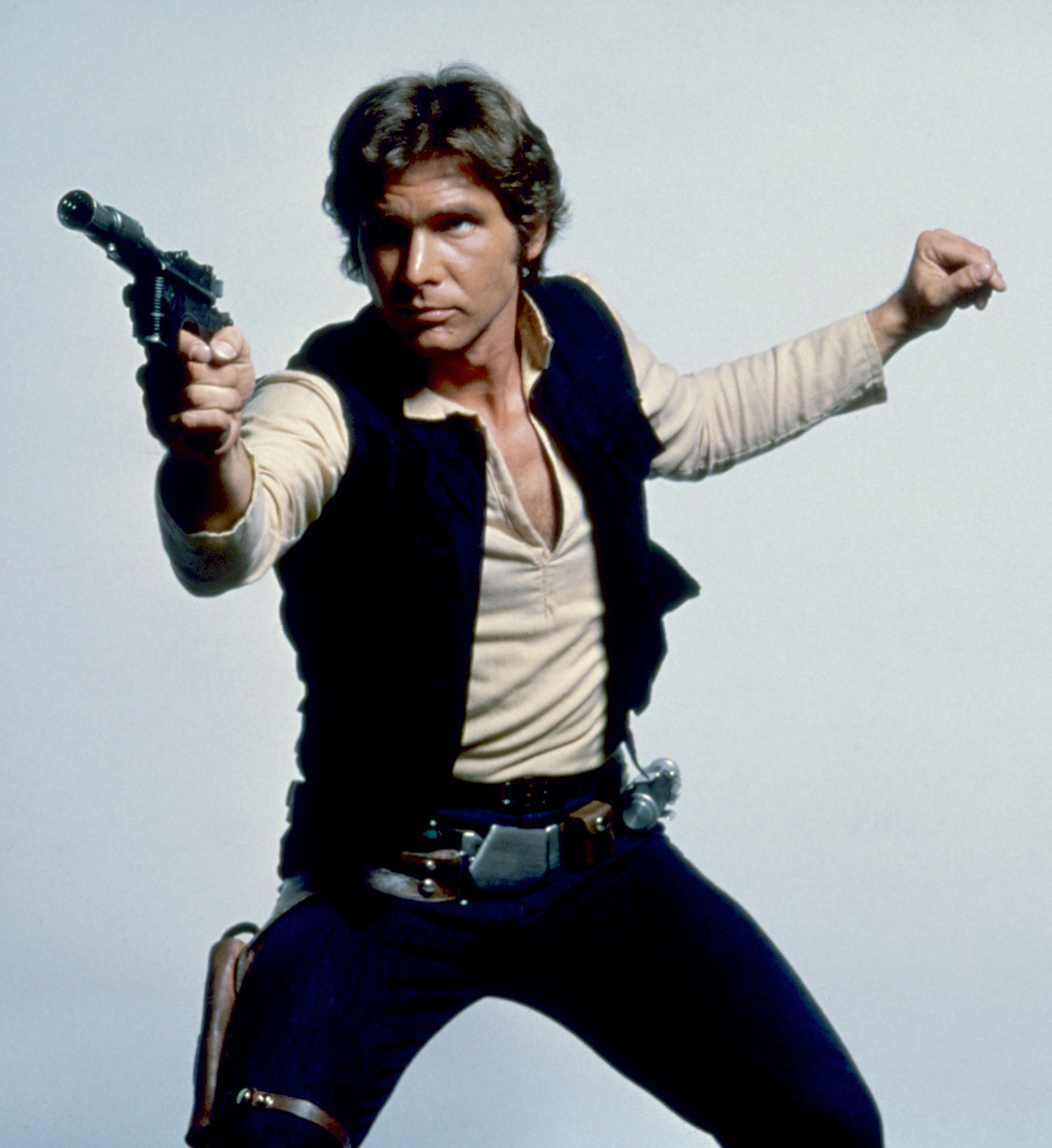

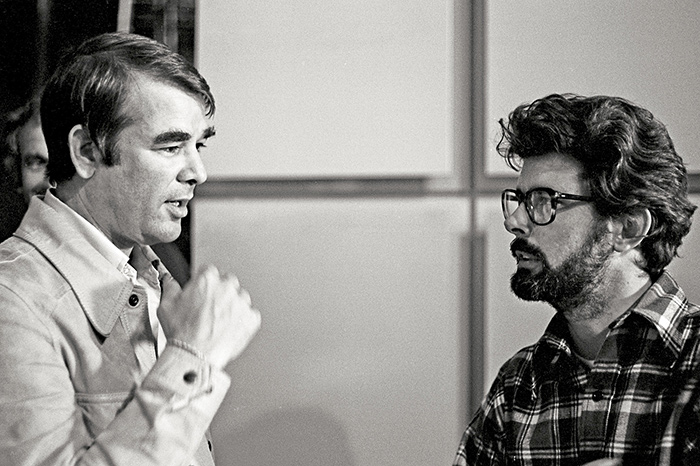

Harrison Ford arrived in England on April 1, a few days before the location group returned. “The first contact I had with the company over there was for a fitting, at a big costume company in London,” Ford says. “George had made suggestions to the costume designer, who had prepared a costume for me to try on. It included the shirt I wore, but instead of the small collar, it had a huge Peter Pan shawl-type collar. I said, ‘No, no, no. That’s wrong. Can’t wear that.’ So they took it off. Later on the set, George never missed the collar. He had a concept of the costume, but it was loose.”

While Lucas and Ford had an easy rapport, apparently Kurtz retained some leftover apprehension from his interactions with the actor more than four years before. “I heard that Gary had prepped certain members of the English production group with information that I might be very difficult to deal with,” Ford says. “That was based on his experience with me on American Graffiti, where most of Paul LeMat’s antics were pinned on me.”

Moving back to London and EMI/Elstree gave some members of production a chance to regroup. “As soon as we got back to the studio, I told John Stears we had to fix the Artoo unit so that we didn’t have so much trouble with it,” Kurtz says.

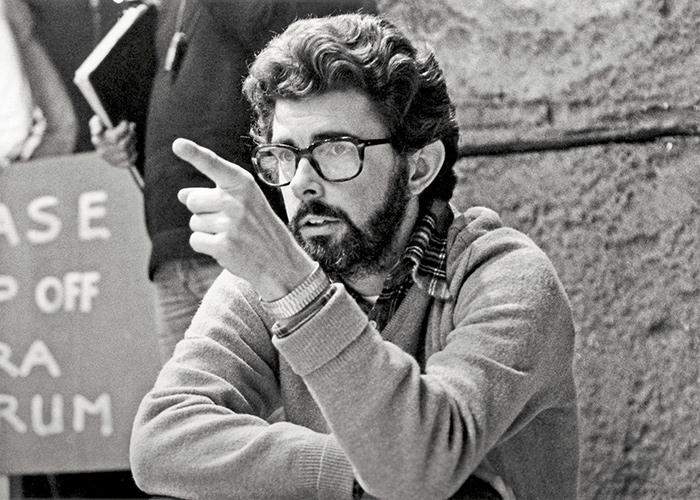

“To move forward you have to be stubborn and persistent,” Lucas says. “I went back to England and got a lot of sleep, because we returned on a weekend. I got up the next morning and started all over again. I was hoping things would go better. But they didn’t.”

While life on the set could be much more controlled than it was in the Tunisian deserts, it was also strictly regulated by unions and long tradition. The workday began at 8:30 with a tea break around 10; a copious lunch was served from 1:15 to 2:15, with tea at 4 PM. During the tea breaks, work would continue, however, as only the assistants would stop and grab things for the people running the set. After wrap, crew members would often go out for a drink nearby. “That helped us a lot because we could run down to the pub, see if anyone was there, and ask a question or get them to come back,” Kurtz says, as often Lucas and others would be working out the next day’s shoot long into the night.

The crew would not work overtime unless it had been accepted by a vote earlier that morning. Even if they were in the middle of a scene, the workday would stop dead at 5:30 PM—which immediately caused problems. Scenes that could have been finished in the evening were completed the next day, which meant that a two-hour stage move that normally would be accomplished at night would take place during the day—translating into huge amounts of lost time, and wearing quickly on the independent-film-schooled Lucas.

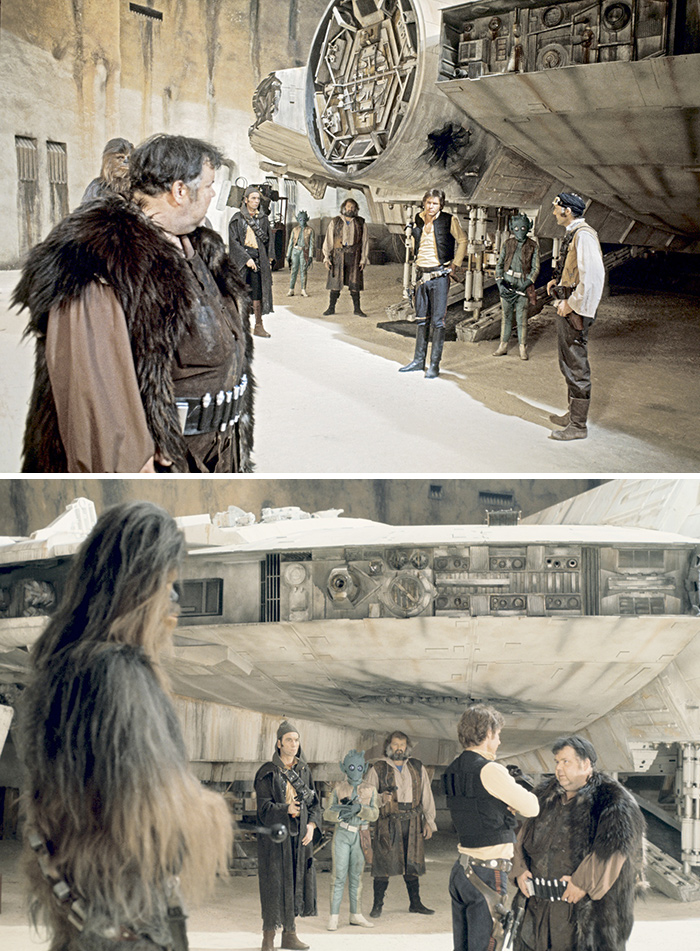

On Friday, Day Seventeen, production moved to one of the largest sets: Docking Bay 94, in which the Millennium Falcon was housed. Built in what must have been close to record time, the exterior of the pirate ship had been painstakingly re-created by the construction crew and art department, duplicating exactly the miniature sent over from ILM (even down to the mistakes—like an edge of styrene coming out that was too thick to be the ship’s aluminum skin—much to the amusement of Joe Johnston). “That sort of preconceived idea is very dangerous,” Barry says, “because you find yourself building things that don’t fit in any stage.” True enough, only half the Falcon wound up fitting on Stage 3, and it was so large that moving it was out of the question; instead different sets would be built around it.

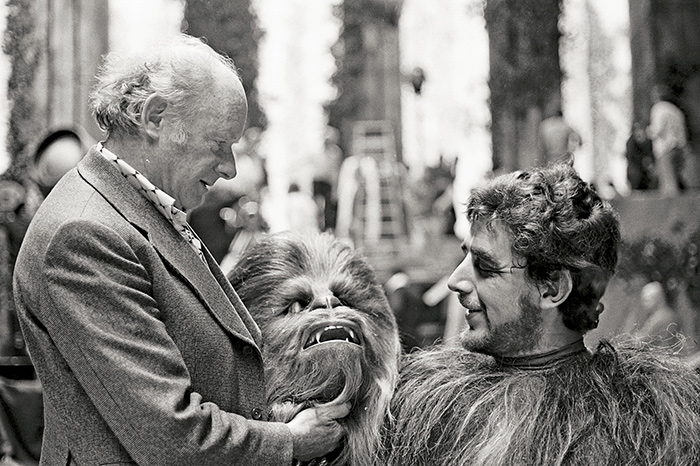

Friday was also the first day on set for Peter Mayhew, who had been cast as Chewbacca the Wookiee and who had signed his contract on February 27, 1976. Mayhew’s route to Star Wars had begun when “some reporter wanted to do a story on people with big feet,” Mayhew says. “A producer saw the article and cast me to play Minoton in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger [1977]. One of the makeup men on Sinbad was also creating the Wookiee costume, and he suggested me to the producers of Star Wars. So four or five months after playing a Minoton, I was playing a Wookiee. I was the new boy, new costume, and everything was strange.”

“He’s just the most gentle—that’s how smart George is,” Hamill says of Mayhew’s casting. “I mean, he found this big, gangling sweet guy. He was so shy at first.” Through both acting stints, Mayhew kept working his day job as deputy head porter in a London hospital, though apparently his employer didn’t take kindly to Mayhew’s suddenly varying schedule.

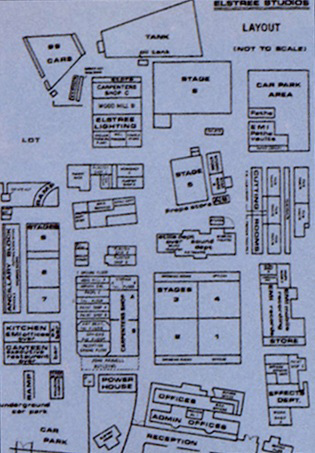

The layout of EMI Studios (aka Elstree Studios) in Borehamwood, England.

Philip Strick from Sight and Sound magazine visited the studio at about this time and wrote: “All nine [sic] stages were festooned with amazing architecture, including a labyrinth of curling corridors, ramps, and airlocks, a vista of one-dimensional rocket tubes, and a spectacular pirate spaceship, brooding like a huge concrete manta-ray over the meteor holes that had been burned into it.”

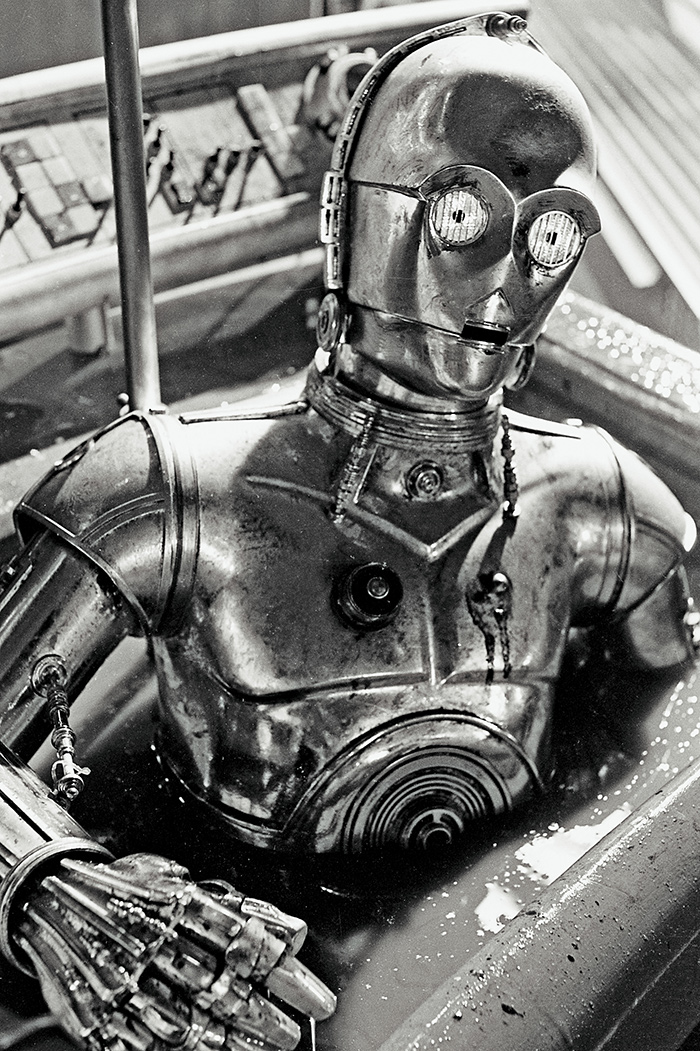

Scene 27, the protocol robot’s oil bath, was also completed that day—though Daniels’s costume predicament was not improved by the return to London. “I stood on a special effects platform and, as the oil bath scene began, the platform was lowered by three men into a big tank containing a mixture of oil and colored water,” he says. “I’d had the foresight to have them heat the mixture first—for this was still winter in England—but it was a fairly disgusting experience, feeling this warm oil seeping up between the costume and me. By the end of the day, we’d done it so many times the sticky tape came off and my leg began to float away. I also had a little ear microphone to hear Mark speaking, and what is so wonderful about those instruments is that you can hear anyone near the microphone, so you listen in on some very outrageous gossip.”

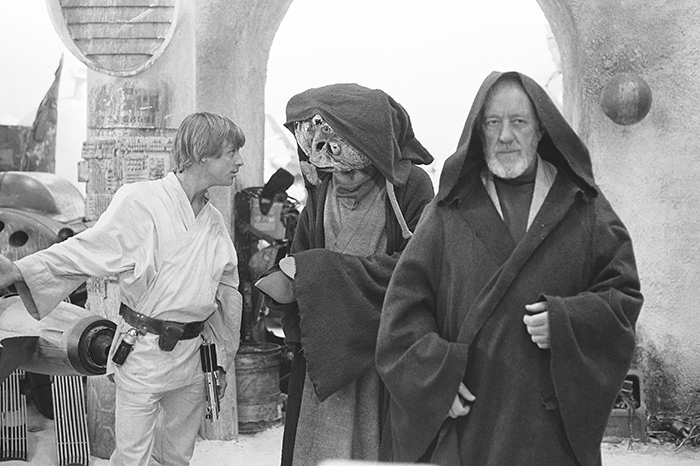

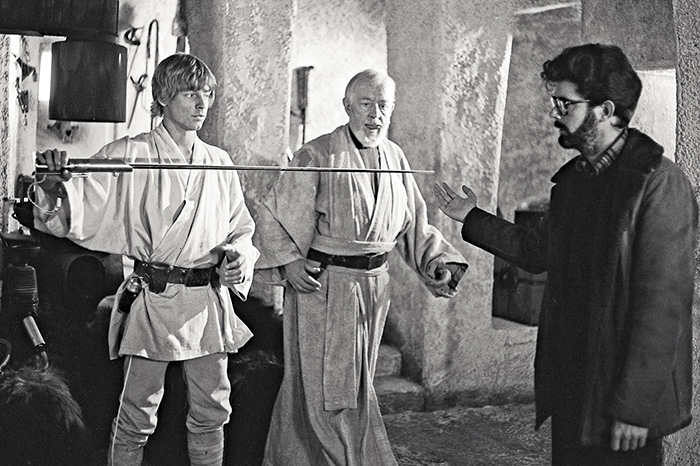

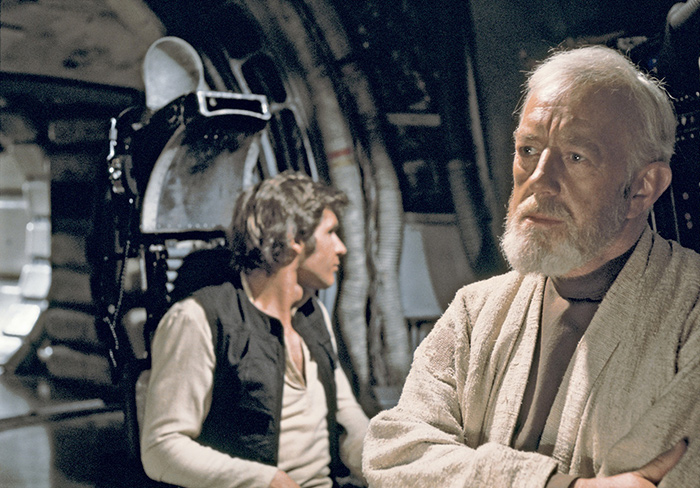

The biggest problem—a potentially film-destroying event—had to be counteracted by Lucas during a strategic lunch on one of their first few days back. In the intervening time between Tunisia and his arrival at the studio in London, Guinness had mulled over the death of Obi-Wan, and was not at all happy about it.

“We went to a restaurant and sat down,” Lucas says. “He was terribly upset. He was ready to walk off the picture—he said, ‘I’m not doing this.’ He didn’t like the idea of being a ghost. That’s the part he really didn’t like, the idea of giving yourself up willingly to join the Force. So I had to convince him to come back on the picture. That was a very long lunch, during which I had to explain why I was doing it and what I was doing and how. I explained that in the last half of the movie he didn’t have anything to do, it wasn’t dramatic to have him standing around, and I wanted his character to have an impact. Once I explained it was much better for the movie, he looked at it and said, ‘You’re right. This is much better.’ He started to think about what he was going to have to be doing and how it would’ve been embarrassing to simply be standing around without much purpose.

“The idea of having Ben go on afterward as part of the Force was a thematic idea that was in the earliest scripts,” Lucas adds. “It was really a Castaneda Tales of Power thing.”

Afterward Guinness spoke to Hamill, who says, “Alec thought it would be far more effective if he sacrificed himself.”

Off screen, Gary Kurtz interviews Alec Guinness at Elstree Studios, asking him about

his character and if it was difficult to act with the “robots.”

(0:51)

In the garage set Luke points to a hologram of Princess Leia that would be added in postproduction.

C-3PO takes a refreshing oil bath—that was anything but for Anthony Daniels.

SCS COMP: 33; SCREEN TIME: 30M 13S.

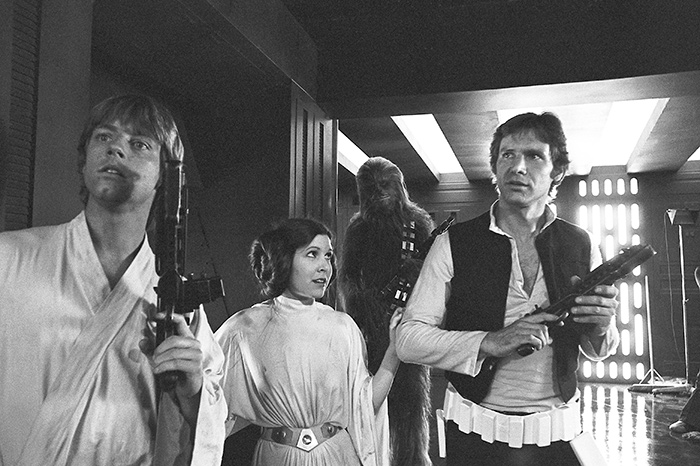

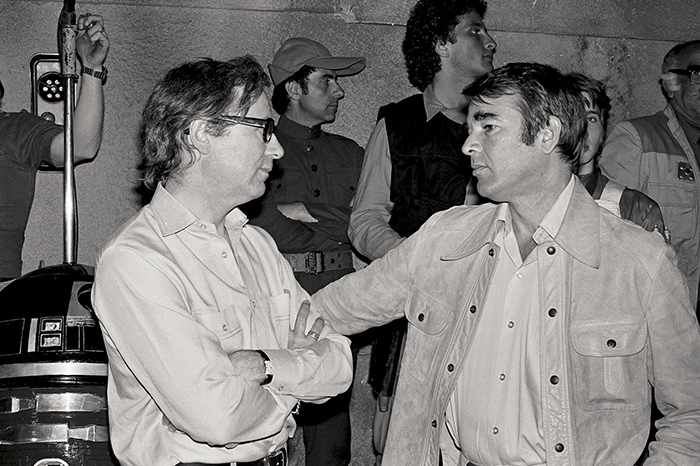

Declan Mulholland (Jabba the Hutt) on Stage 3 with Harrison Ford (Han Solo) and Peter Mayhew (Chewbacca).

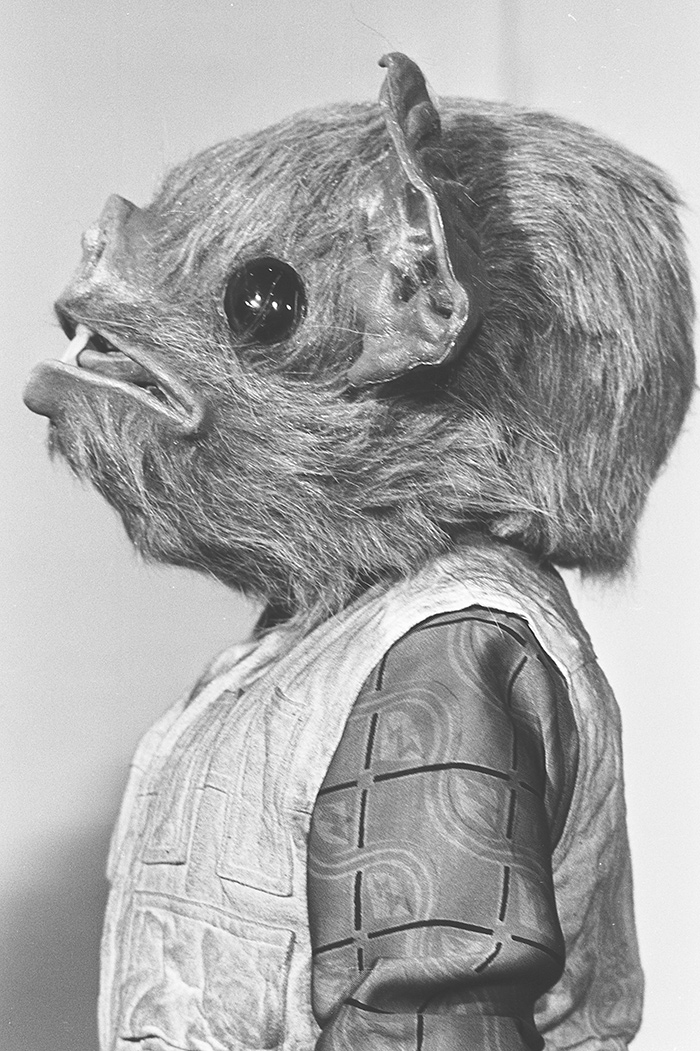

Paul Blake (the “Alien”) is fitted with a mask while another extra holds his alien hands.

REPORT NOS. 18–24: MONDAY, APRIL 12–THURSDAY, APRIL 22, 1976

STAGE 3: INT. DOCKING BAY 94, SCS: AA53 [JABBA AND SOLO]; 58 [LUKE AND COMPANY ARRIVE]; B58 [HAN FIRES AT STORMTROOPERS]

STAGE 6: INT. CANTINA, SCS: 50 [OBI-WAN AND LIGHTSABER]; ZB50 [LUKE AND BEN MEET HAN]; AA50 [HAN AND ALIEN]

STAGE 8: EXT. MOS EISLEY ALLEYWAYS, SCS: 53 [LUKE HAS SOLD HIS LANDSPEEDER]; 56 [SPY TRANSMITS FALCON’s COORDINATES]; A58 [SPY TALKS TO STORMTROOPERS]; C50 [DROIDS HIDING]

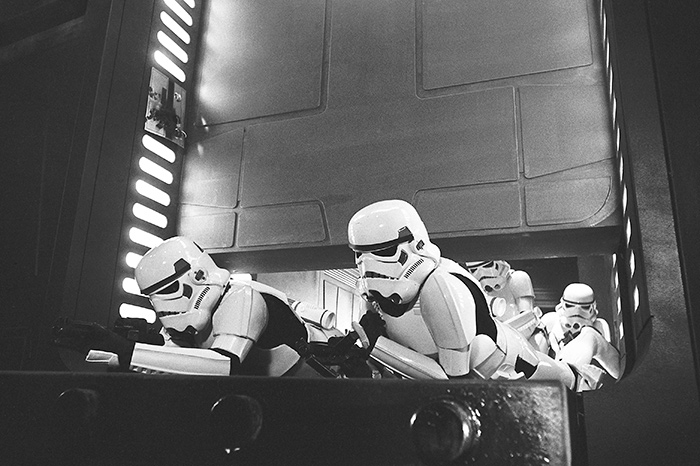

Monday saw everyone back on Stage 3’s Docking Bay 94. Declan Mulholland returned for his second day as Jabba the Hutt, along with Bill Bailey, Paul Blake, and Peter Diamond, who played his gangster henchmen. Filming and retakes continued for several days of first- and second-unit work, as progress reports recorded various difficulties, including a defective 40mm lens and an accident with stuntman Reg Harding, who, as a stormtrooper, had a bolt inside his helmet dig into him during a fall.

“The sets were terrific and there were all these different sorts of people wandering about,” Mulholland recalls. “Harrison Ford was pleasant and got on with the job. He was just one of the lads, really. We had a few chats in between takes.”

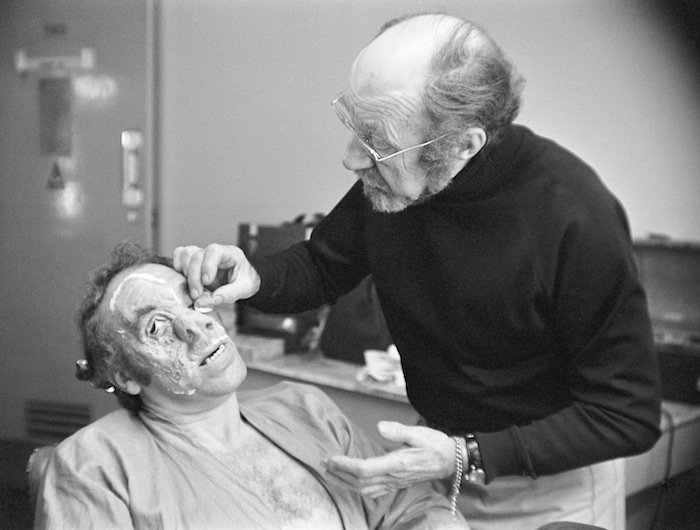

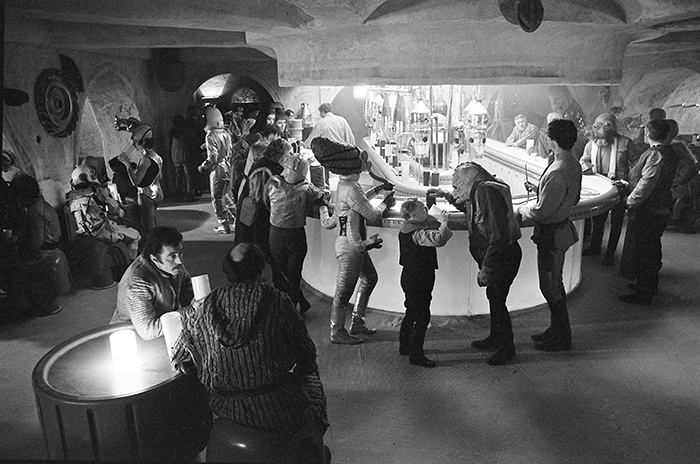

On Tuesday the camera crew set up to film the interior cantina scenes—the set piece that had been in Lucas’s mind since 1973. The entrance of Luke and Ben into the bar—and the reveal of all the strange creatures—was meant to come as a surprise to audiences. “George didn’t really want to go way-out on the people, other than the creatures,” Stuart Freeborn says. “Because that was supposed to be a kind of ‘shock’ scene. Everything’s pretty normal up to that point in the film. Indeed, we weren’t to introduce odd things like Mr. Spock before that scene.”

To prepare the exotic cantina clientele, Freeborn worked with his wife and son, and employed another six assistants. Together they made life casts with rubber and foam pieces: fake noses, twisted lips, false teeth, cheek enhancements. “For the so-called ugly humans, I had photographs taken of all the artists,” he says. “I did some sketches on the photographs, which I got okayed by George Lucas, and built them up from there.”

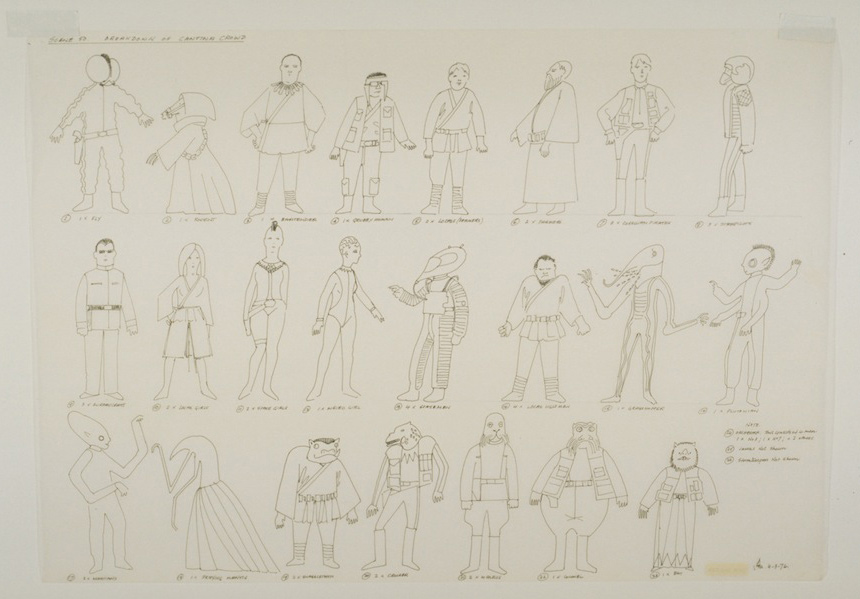

“What happened with the cantina costumes is that George and I sat down and created a complete chart,” Mollo says. “I drew a little figure for each type of person, and he decided he wanted so many peasants, so many Martians, so many space pilots, so many pirates—and that was all tied in with the heads which Stuart had designed or could produce. Then it was just a question of getting together with Stuart and making sure the heads and the costumes fit together.

“As usually happens with a crowd is that you do it on the day,” he adds. “You truss them all up on the day, and change them around if you see something you don’t like.”

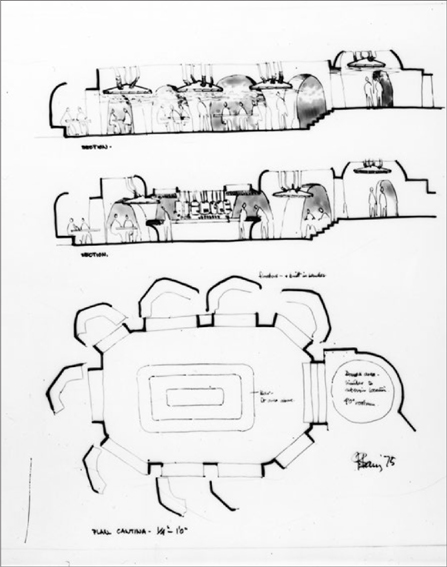

Barry’s sketch, based on Lucas’s instructions, of the cantina and alcoves.

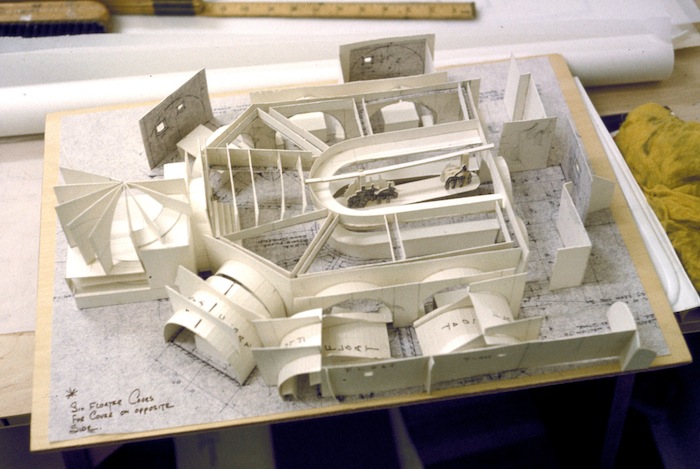

A cantina maquette contains a note saying that it will have “six floater [al]coves for cover on opposite side.” A “floater” wall is a wall that can be removed from the set for camera placement if necessary.

The final set. Among the crowd were a few in-jokes: Five spacesuits were actually outfits taken from Western Costume; one was modeled on a character from Destination Moon, and another on the television show Lost in Space; at the bar was a character referred to as “mini Han Solo,” because he was dressed the same as Ford.

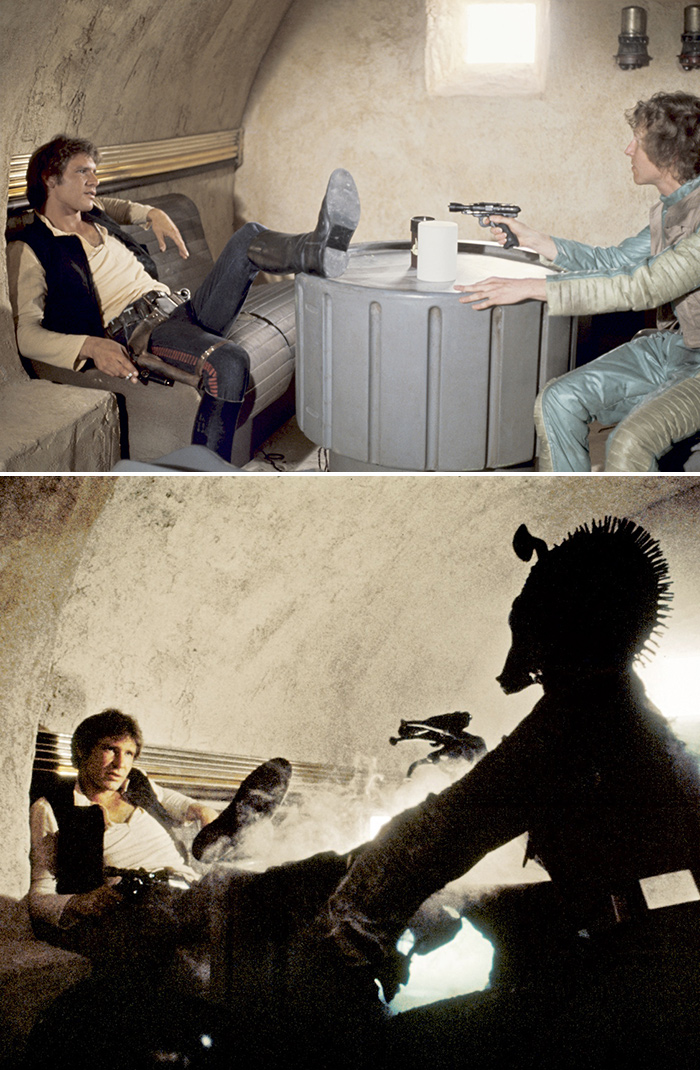

Ford in the alcove with Paul Blake (without and with mask).

Makeup artists work on various cantina denizens, who are then filmed.

“Breakdown of Cantina Crowd,” costume lineup sketch by John Mollo.

After Mollo had seen to the last costume details of the forty-two extras, they were escorted onto the cantina set. “I wanted a round bar,” Lucas says. “I drew out a rough plan, with a lot of little alcoves around the side, and I wanted a big shaft of light coming down the center.”

“George wanted a main part for where the action was,” Barry says, “and then those cubicles off to the side—a secret part where you could have a secret discussion.”

That secret discussion, filmed on April 20, was Harrison Ford’s first dialogue scene with Alec Guinness. “I’ve always been impressed by Guinness, man. It just scared the shit out of me that I was going to have to do scenes with him,” Ford says. “Before I even went over there, I would think about it—he could have been any one of a thousand monsters. But he turned out to be an honest, simple, direct kind of guy, which made working with him much easier. And he was like all good actors: prepared and ready.”

“Alec Guinness had a very mischievous sense of humor,” Lucas says. “He would give me a hard time every once in a while, making me explain things that didn’t have to be explained. He wanted me to go through the drill. He loved to do that to me. I knew he was playing, but he would be smiling to himself almost saying, I’m not going to let you get away with it that easy.”

A printed daily of Ben swinging into action in the cantina, at Elstree, mid-April

1976. Note that you can see Lucas’s reflection in the protective glass in front of

the camera at the end of the take.

(0:18)

“His eye is a very pure eye,” Guinness says of Lucas. “I trust that. And little things I’ve heard him hesitate about … He’s kind of like a litmus paper; you can judge off him very well as to what’s going on. He has a total passion for what he’s doing; I don’t think I’ve ever come across anyone so immersed in film. I have an idea that he goes to bed in it—wrapped up, you know, in the actual material.”

The same alcove was also used for a scene with Ford and Paul Blake, a friend of Anthony Daniels. Although later in the script Jabba refers to him as “Greedo,” during the cantina scene he is simply called an “Alien.” A newcomer, Blake was appropriately impressed. “My first day on the set, the cantina was filled with incredible aliens. The booth sections were extremely restricted, so my movements were quite stiff.”

However, because Freeborn was ill at the time and not able to finish his work, Blake’s mask was not very expressive, nor his hands very maneuverable, so he had difficulty grasping his blaster and pointing it at Han. Indeed all the faces were somewhat disappointing. “Stuart was rushed to try to create the cantina creatures while we were in Tunisia,” Lucas says, “because we had moved the cantina sequence up a week in the shooting schedule and I kept adding monsters all the time. But a few weeks before we were going to shoot that sequence, Stuart got sick and had to go to the hospital, so we didn’t get all the monsters finished that we wanted. The ones we did have were the background monsters, which weren’t meant to be key monsters.”

Two other day players in the cantina, Angela Staines and Christine Hewett, played Han’s female companions (or “space girls”), while Rusty Goff, Gilda Cohen, Marcus Powell, and Geoff Moon were listed as “contract artistes,” adding to the total crowd. Ted Burnett played the bartender who tells Luke he can’t bring in the droids. “The parallels between the film and real life were amazing,” Hamill remarks. “When we got back to England, Harrison came into the picture and had so many ideas and just new perspectives on a lot of things. There were new characters coming in, so Threepio and I were split up a lot and he felt a little left out.”

Mayhew, on the other hand, was quickly adjusting to his role and creating a relationship with his on-screen companion, Harrison Ford. “You first see Chewbacca in the cantina background talking to Obi-Wan… Bang, bang, bang, the whole scene worked,” he says.

A printed daily from April 21, 1976, of Harrison Ford as Han Solo turning the tables

on Greedo (Paul Blake, who speaks his lines off camera; Lucas can be heard saying,

“Cut”). Note that during the pickup at the end of the clip, you can hear the sound

of an ejected shell from Han’s blaster falling on the floor, as Christian’s prop fired

real blanks.

(1:19)

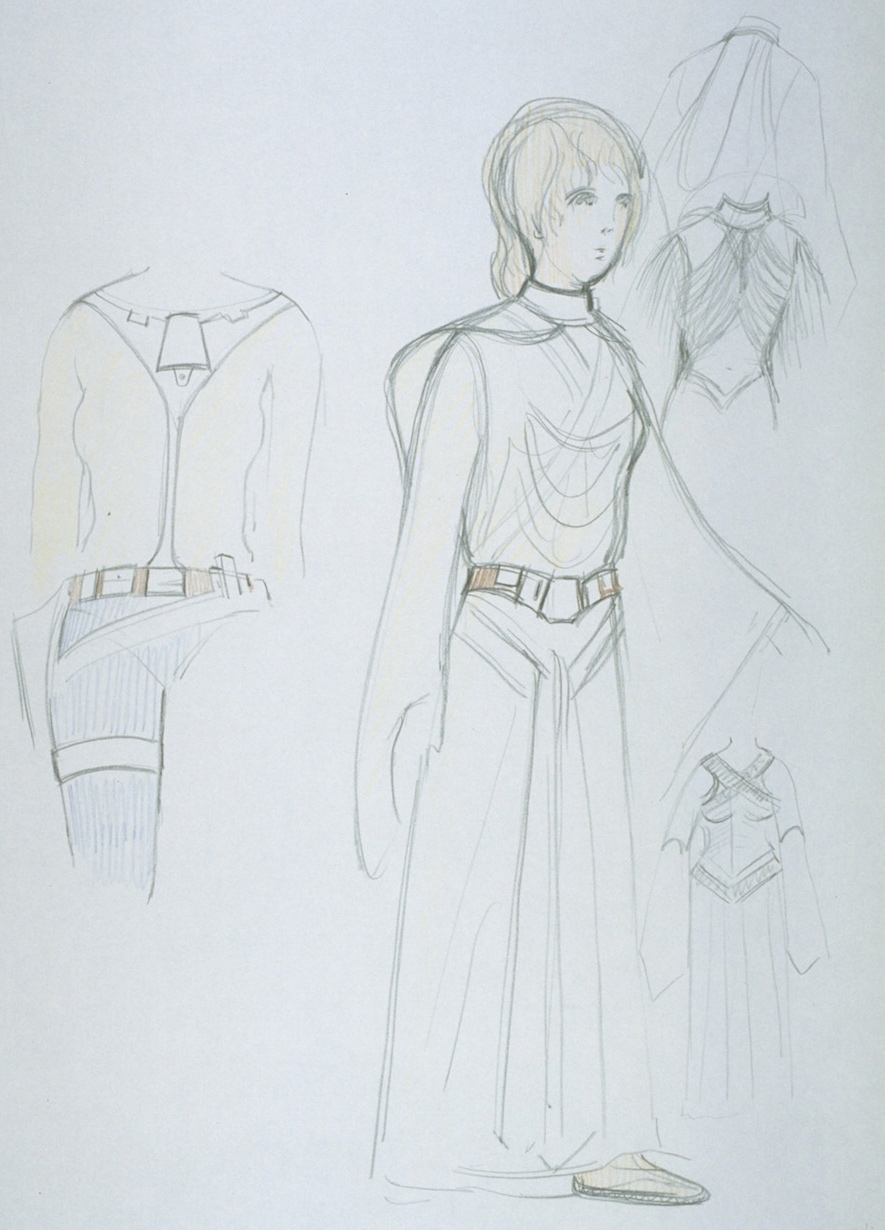

April 20 was Carrie Fisher’s first costume fitting, at Berman’s, the actress having arrived the previous day. Before leaving the United States, she had been worried about her hair and her wardrobe. “One of the costume sketches had me wearing a little Peter Pan leotard,” Fisher says. “But it was rejected. I was also scared about what they were going to do to my hair, because I had so much hair put on me, two different sessions of that—I had at least thirty hairdos tried on me. And they didn’t like it when I got to London. When I arrived, they were shooting the Mos Eisley thing. The hairdresser woman Pat [McDermott] put on me what she had as an idea for the hair—and that was it. I went into the cantina and showed George the hair, and he said, ‘That’s okay.’ Then they put me in a nice white dress and put dirt all over it. And from the first day on, they put a gun in my hand with charges in it, took me to a sound stage, and had me practice shooting it.”

“For Leia’s costume, what we did was to slit it up the side a bit so she could move around,” Mollo says. “We had special boots made for her, too. Jean Harlow was the type, so we looked through a few Vogues and came up with that slightly different belt.”

The same day that Fisher arrived, new script pages dated April 19 were circulated among the actors, and a copy was sent to Fox back in the States. “George went off to shoot, but of course a lot of blue pages were coming in,” Alan Ladd says. “That’s when they decided about the death of Obi-Wan.”

Another alteration, smaller in scope but with lasting impact, was the last of the name changes. Luke Starkiller became Luke Skywalker. “That I did because I felt a lot of people were confusing him with someone like Charles Manson,” Lucas says. “It had very unpleasant connotations.”

Skywalker was of course the original name for the general in the treatment, but for a long while Lucas didn’t think it was strong enough. No scenes had to be reshot, however, as Luke’s last name wouldn’t be spoken until he finds Leia in her prison cell: “I’m Luke Skywalker … I’ve come to rescue you!”

SCS COMP: 42; SCREEN TIME: 39M 32S.

Costume sketches of Leia’s dress by McQuarrie and Mollo.

Fisher wearing the final product. Mollo’s sketch asks the question whether Leia would be wearing jewelry on her wrist and whether she will be wearing sandals, shoes, or boots; it also indicates where the slit in her dress should be made.

Leia costume concepts by John Mollo.

Carrie Fisher (Princess Leia) testing out hairstyles, possibly.

Although ostensibly an exterior, the Mos Eisley street was built on Stage 8.

Extras were suited up in alien costumes and masks.

A strange encounter between a small person and a larger one on stilts, Peter Barbour, was filmed.

REPORT NOS. 25–26: FRIDAY, APRIL 23–MONDAY, APRIL 26, 1976

STAGE 7: INT. BEN KENOBI’s CAVE, SC: 42 [OBI-WAN VIEWS LEIA’s MESSAGE, ETC.]

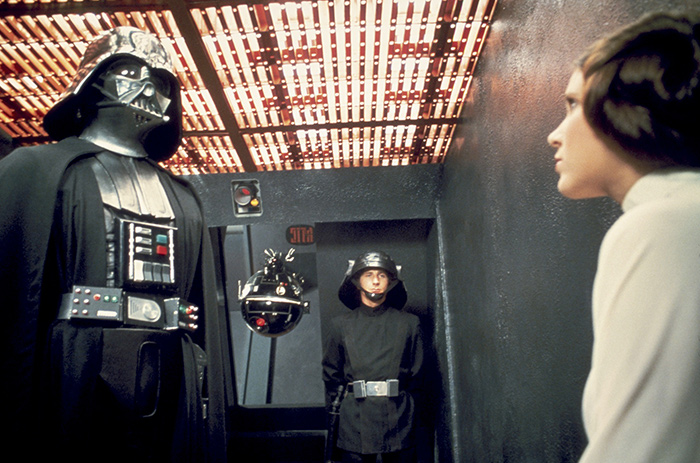

STAGE 2: INT. DEATH STAR, SCS: 86 [KENOBI SNEAKS AROUND]; 111 [VADER FOLLOWS KENOBI]

The long scene in Ben’s home took one day of first unit and another day of second unit to complete, with pickups done a few days later because of a lens problem. “We were asking ourselves, ‘Ben Kenobi—what does he do in his spare time?’ ” Barry muses. “You have to decide that before you can do his apartment. We had steps and seats, which we put furs and things on top of.” The pared-down dwelling was ultimately given a rug, a trunk for the lightsaber, and what look like mementos. But the décor had to play second fiddle to the dialogue between Ben and Luke, which formed one of the two or three main expository scenes of the film. In it, the Force is explained, their mission revealed, and the lightsaber unveiled.

In Ben’s home on Stage 7 with the lightsaber (which glowed when viewed through the camera).

The middle child of seven brothers and sisters in a family that moved often, including two and a half years in Japan, Hamill adapted easily and enthusiastically to life on the set, and could relate to his character’s family problems. “I think Ben Kenobi is like the father I always wanted, because I can’t really relate to my uncle,” Hamill says. “My uncle is an isolationist and wants to just have a farm. But when I find out that Guinness knew my father and was involved in the same sort of things, I think there’s a great connection there—and it was easy for me because I couldn’t help but be in awe of the actor who was playing it.”

“I tried to make him uncomplicated,” Guinness would tell The Sunday Times on May 2, a few days later. “I’m cunning enough now to know that to be simple carries a lot of weight. The laser sword seems to be a marvelous weapon. It’s rather like a Japanese sword with a row of laser buttons. But I must confess I’m pretty much lost as to what is required of me … What I’m supposed to be doing, I can’t really say. I simply trust the director.”

It would also seem that Guinness was relaxed enough to improvise, for while the script had his line as “You must do what you feel” when Luke hesitates about becoming a Jedi Knight, what Guinness said was, “You must do what you feel is right, of course.”

John Stears and company had worked out the problem of the lightsaber just in time for their scene. When Hamill “ignites” it, what he’s really holding is a spinning wooden sword, partly coated with a reflective material that, when photographed by Gil Taylor through a half-silvered mirror, looked like it was illuminated from within.

While Hamill and Guinness did repeated takes, Daniels sat quietly in the background, worrying. “My feet crossed beneath me in a yoga position, I moved up only with the help of Alec and Mark,” he says. “But I had to warn Alec that I was really a lethal instrument, because I could very happily chop off fingers without knowing. If they put their fingers where the arm went in or where the knees joined, I would just crack their fingers without being at all aware.”

At 5:30 PM Lucas and company were still filming the cave scene. The director had already been obliged to stop scenes several times in midstride and wasn’t about to do so again. “When we were on location we could shoot a twelve-hour day,” he says. “But when we got back to the studio suddenly they were chopping me off at 5:30. I said ‘Wait a minute!’ Because what happens is you get a scene completed, except one or two shots that would’ve taken about forty-five minutes to finish—but they’d say no. If instead you finish the scene at the end of the day, then you move to the next stage that night; you don’t take up shooting time for it—because they won’t shoot after 5:30, but they can move their equipment. I would have picked up an hour or two every day, but they wouldn’t let me do that.”

“It’s a holdover from the labor situation in England,” Kurtz explains. “It would’ve been helpful had they decided to work past five thirty, but they never did, which annoyed George quite a bit some days, particularly when he only had one or two shots left to complete a scene—forcing him to make a time-consuming set move in the middle of the next morning.”

“But there was a provision in the contract that said if I was in the middle of a shot, I could take what they called a ‘quarter’—fifteen minutes,” Lucas adds. “I was allowed to take up to four ‘quarters’ to finish a shot. So I set up a very elaborate, long dolly shot in the Obi-Wan scene, and I took the four quarters—but the crew was very angry with me. I was a bearded kid, around thirty years old. I was just this crazy American who was doing this really dopey movie.”

That Friday evening, after the first unit wrapped Ben’s cave, Lucas and Barry did a walk-through of a Monday set, the first on the Death Star: a simple corridor in which Darth Vader catches a glimpse of Obi-Wan and follows him. The following Monday the panels Lucas requested during the walk-through to close off the corridor had been added—and Darth Vader, played by David Prowse, quickly completed his scene.

“George told me he was making a space fantasy and asked me to consider playing either Chewbacca or Darth Vader,” says Prowse, who had played many a large person in films such as A Clockwork Orange, and who owned a chain of weight-lifting gyms that made him independently wealthy. “I turned down Chewbacca at once. I know that people remember villains longer than heroes. At the time I didn’t know I’d be wearing a mask. And throughout production I thought Vader’s voice would be mine.”

Another looming problem was taking shape in the form of John Jympson. While Lucas had been in Tunisia, rushes had been delivered to the English editor, who had started cutting the scenes together. However, Lucas hadn’t been able to see the dailies himself until now, and when he started viewing Jympson’s assemblies, he wasn’t happy: Jympson’s selection of takes was questionable, and he seemed to be having trouble doing match-cuts. Yet, just as Lucas had been patient with the robot problems, he was hesitant to criticize the editor for similar reasons: Everyone in the production was operating without enough prep time and, in this case, with less guidance than perhaps needed. “Jympson is in an impossible position, cutting material that I haven’t even talked to him about,” Lucas said to one of the crew at the time. “It’s totally unfair for me to judge him now.”

Strangely, it was the editor who became very impatient with Lucas, complaining loudly about how things were being done. “I think the editor was very unsympathetic to George,” Barry would say a couple of weeks later. The situation was all the more uncomfortable for Lucas, who was now coming to grips with the more negative aspects of doing a large-scale production. “His films were always very private before,” Barry says. “Because of the low budgets, no one would see them. So George is now fairly touchy about people seeing rushes, and I can understand his point of view. He knows what he’s going to do with it, but someone else might ask, ‘Well, why does it look like that?’ He doesn’t want people to start losing confidence, in him or the picture.”

SCS COMP: 45; SCREEN TIME: 44M 29S.

The highly reflective floors had to be kept clean for the scenes of Darth Vader (David Prowse) and Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) walking through the hallway built on Stage 2.

Behind-the-scenes footage of David Prowse being dressed in his Darth Vader costume

at Elstree. (No audio)

(1:30)

On June 25, 1976, a gag in which a gonk droid finds itself alone in a Death Star hallway

is shot (this doesn’t make the final cut). Jack Purvis plays the droid. (Note that

colored film “slugs” in the sequence indicate where film has been taken from this

daily and used in the final edit, or one of the early edits; the slugs fill up the

holes so the audio is still in sync.)

(0:45)

REPORT NOS. 27–32: TUESDAY, APRIL 27–TUESDAY, MAY 4, 1976

STAGE 2: INT. DEATH STAR, SCS: BA53 [VADER SPEAKS WITH A COMMANDER]; 113 PART [HAN AND CHEWIE JUMP THROUGH BLAST DOORS]; 107 PART [HEROES VIEW FALCON THROUGH BAY WINDOW]; A110 [LUKE FIRES AT STORMTROOPERS]; B110 PART [LUKE AND LEIA ARRIVE AT CUTOFF BRIDGE AND SWING ACROSS]

STAGE 4: INT. DEATH STAR CONTROL ROOM, SCS: A124 [VADER: “THIS WILL BE A DAY LONG REMEMBERED …”]; D42 [VADER AND TARKIN DISCUSS LEIA’s RESISTANCE TO MIND PROBE]; SS225 [TARKIN: “EVACUATE?! IN OUR MOMENT OF TRIUMPH?”]; 66 PART [LEIA: “THE MORE YOU TIGHTEN YOUR GRIP …”]

STAGE 1: INT. DEATH STAR CONFERENCE ROOM, SCS: 22 [VADER: “I FIND YOUR LACK OF FAITH DISTURBING”]; 76 [REPORT PER DANTOOINE]; 89A [VADER REPORTS OBI-WAN’s PRESENCE TO TARKIN]

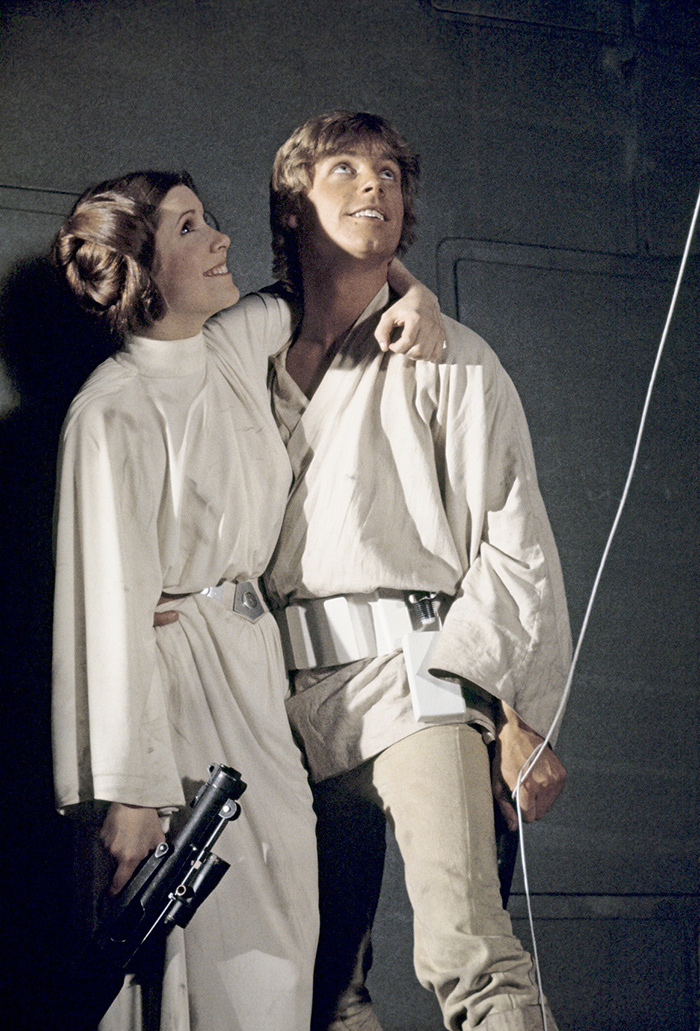

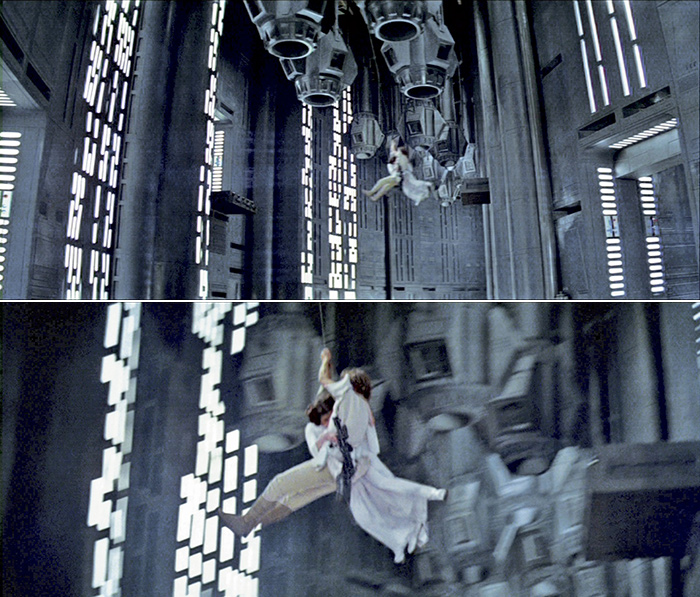

While Tuesday’s filming was uneventful, Wednesday, April 28, featured Luke and Leia’s swing across the chasm. Though the stage floor was only about a dozen feet below—a matte painting would be added much later to simulate the bottomless pit—harness expert Eric Dunning had been called in on April 21 for an evening meeting with department heads to discuss logistics and safety.

“First they practiced with two puppets on one string dangling from the roof just to see if the rope was strong enough,” Fisher says. “Then they put all these cardboard boxes down on the ground, but I couldn’t see how the boxes were going to prevent me from breaking any bones. After kissing Mark, George wanted me to say, ‘For luck,’ which sounded obscene because the words blended into one another. Then I was supposed to shoot the gun and swing. On the swing across, I was going to hold the gun, which is real heavy, and that scared me because I thought I’d drop it. I was also afraid my hair was going to fall off. But it was funny that day— everyone was laughing—and we only had to do it once.”

A printed daily from April 27, 1976. In a gag that won’t make the final cut, the heroes,

just out of the garbage masher, conceal their weapons from Imperial officers in a

Death Star corridor (Chewbacca doesn’t conceal his, which may have been one reason

to cut the gag).

(0:34)

Harrison Ford evidently enjoyed playing the somewhat trigger-happy Han Solo.

Harrison Ford, as Han Solo, running through the same hallway that Guinness sneaked through on Stage 2.

“I always knew that I couldn’t get the girl,” Ford says. “Han knows if he gets the girl, it will just be a one-night stand.”

Leia’s “ear-muff” hairstyle was inspired by photographs taken by Edward S. Curtis of Native Americans and photos of Pancho Villa’s rebel women. “I was a little afraid of it,” Fisher says. “I still am a little afraid of how I am going to look in it.”

The swing was just one of Fisher’s physical performances, which dominated her first days on the film. “I’d be running down a hallway and my hairdo would start falling apart,” she says. “I didn’t like having my breasts taped in. In space, they don’t bounce. Princesses don’t do that, so they taped me.”

Fisher’s first appreciable dialogue occurred with Peter Cushing in the Death Star control room the following Thursday. It was here that she started to understand how Lucas worked with his actors. “Up until the scene with Peter Cushing, I was just running down corridors, and George didn’t talk that much to me,” Fisher says. “But in my scene with Peter, I was doing too sarcastic and George wanted real anger. But I liked Peter Cushing so much that, in my mind, I had to substitute somebody else in order to get the hatred for him. I had to say, ‘I recognized your foul stench …’ But the man smelled like linen and lavender.”

“You see, I always lavishly slosh lavender water all over myself whenever I’m filming,” Cushing says. “I also use a tube of Colgate Dental Cream, because I’m very conscious of bad breath. In fact, if I’m watching a boring love scene in a movie, I can’t help thinking: I do hope they’ve both brushed their teeth.”

While Carrie struggled to muster her anger, Cushing, like his compatriot Alec Guinness, was trying to make sense of his lines. “There was a great deal of the script I didn’t understand,” he says. “Especially the technical jargon. And I wasn’t alone. Many of the stagehands came up to me and asked, ‘What is all this about? I can’t understand a word of it.’ I told them, ‘Neither can I. I’m just saying the lines, and trying to sound intelligent.’ ”

By the end of the day, though Fisher had done her best to sound authentic, she thought she had failed. “George didn’t say anything, which I took to mean, He’s mad,” she says. “The next day, George came up to me with his hand on his beard and said, ‘You were great yesterday.’ And from then on I knew that when he didn’t talk, that it was okay—that less was more with him. Sometimes George would just say, ‘Anything goes. If you want to change the dialogue, you can,’ or he’d say, ‘Faster’ or ‘More intense’—and I didn’t know what that meant, either, at the beginning. I just thought it meant that I was not very good. But then I found out that it was okay. I think Harrison told me.”

A printed daily from April 27, 1976, in which a stormtrooper’s squib continues burning

after the trooper falls. When “cut” is called, stunt coordinator Peter Diamond runs

to the fallen trooper to make sure the stuntman is okay.

(0:21)

Lucas shows Fisher how to hold and shoot the gun—and then she and Hamill swing across.

“Basically I show up and George points me to where he wants me to stand and tells me in his own way what he wants me to do,” Ford says. “When I’m done doing it, we either have a discussion about it, or he says, ‘Do it again, faster and better.’ That’s one of the nice things about George, which gives me real confidence in him. That whatever the problem is, we will be able to work it out when we get there. It’s no big thing. I think that’s the way he likes to work, too.”

“Carrie had just started when she did her scenes with Cushing,” Hamill says. “I came in about eleven and left when they finished. I watched a lot of what Carrie did, but I didn’t want her to know I was on the set because it would have been a distraction. The next day, between takes, I did go and get his autograph. Cushing is the ultimate English gentleman. So distinguished. He was surprised I knew that he was in that Laurel and Hardy film Chump at Oxford, and he told me about working with them. Pictures were taken for publicity, and though I never worked with him, there was no way I would have missed meeting him.”

Hamill had also learned that the fairly recent death of Cushing’s wife had tremendously affected the actor, who wrote about it in great length in his autobiography. “He used to cycle to her grave every morning,” Hamill says. “He was very fragile, but a wonderful guy, really sweet.”

A printed daily (a pickup) of the swing across the chasm, late April/early May 1976.

(0:36)

SCS COMP: 53; SCREEN TIME: 54M 17S.

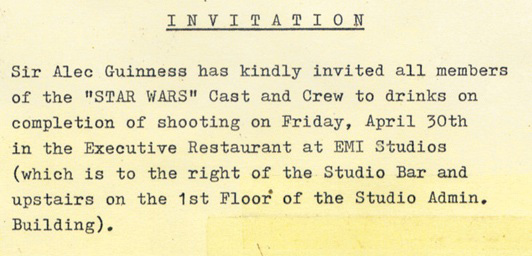

On April 30 cast and crew members received an invitation for cocktails from Sir Alec Guinness.

REPORT NOS. 33–36: WEDNESDAY, MAY 5–MONDAY, MAY 10, 1976

STAGE 2: INT. DEATH STAR, SCS: 83 (CHEWBACCA GROWLS AT MOUSE DROID); 84 [WAITING FOR ELEVATOR TO PRISON LEVEL]; 109 [HAN CHASES STORMTROOPERS]; 110 [CHEWBACCA SEES HAN RUNNING AROUND CORNER]

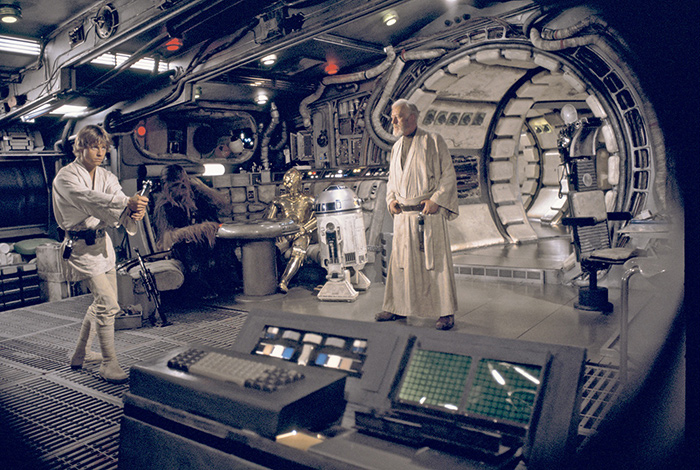

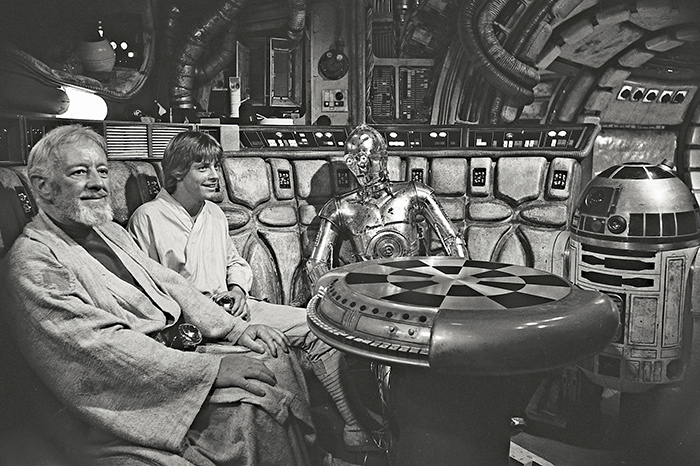

STAGE 9: INT. PIRATE STARSHIP HALLWAY, SCS: 80 [EMERGING FROM SMUGGLING COMPARTMENTS]; 67 PART [LUKE TRAINING WITH SEEKER; HOLOGRAM GAME]; 63 [C-3PO: “I FORGOT HOW MUCH I HATE SPACE TRAVEL”]; AA118 [LUKE: “I CAN’t BELIEVE HE’s GONE”]; A119 [SOLO: “WE AREN’t OUT OF THIS YET”]

Back in the United States, ILM continued to work on the plates for front projection with an increasing sense of doom. They were spending around $30,000 per week now on operating costs, but were hopelessly behind schedule. “As a result of the six-week delay and a couple of other things, we were behind just about the period of time that the hiatus encompassed,” Dykstra says. “So my head was in a shit because it looked like we weren’t going to have the plates out on time and people were getting really depressed. They were working really long hours, but they weren’t happy about what they were doing because they knew it was second-rate. But we felt we had to do it because it was going to cost $10,000 a day to have a crew sitting around if we didn’t have the plates out on time.”

Their forward progress hadn’t been helped by the departure of ILM production supervisor Bob Shepherd just as principal photography had begun. But he had previously committed to Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. “Had someone been here who had the power to do things George would accept, it wouldn’t have taken so much time,” Shepherd says. “John Dykstra said to me, ‘If you’re going to leave then you’ve got to find someone else to do what you did.’ But I didn’t know anybody else.”

Shepherd was eventually replaced by Lon Tinney, but John Dykstra’s job hadn’t been made any easier. One bright spot at Van Nuys was an April 1976 hire, Dennis Muren, who was chosen to work with Richard Edlund in the camera department in order to help move things along. “I was very much aware of the project for about a year and a half before I got on to it,” Muren says. “I’d heard that John had gotten the job, so I called him up and I showed him some of my footage, but I didn’t hear back for about ten months, so I thought the show had folded. Then all of a sudden I got a call to come on in and meet Richard Edlund and see the place. They had already been set up there for months; they were almost hiding out, and it was just a neat place. I didn’t know quite what the quality of work was going to be and I’d never seen that sort of electronic equipment before, so it seemed like an opportunity to try and figure the stuff out, plus meet a lot of people that I didn’t know. I was hired on to shoot backgrounds of stars moving by and planets for the foreground spaceships that Richard was going to be shooting.”

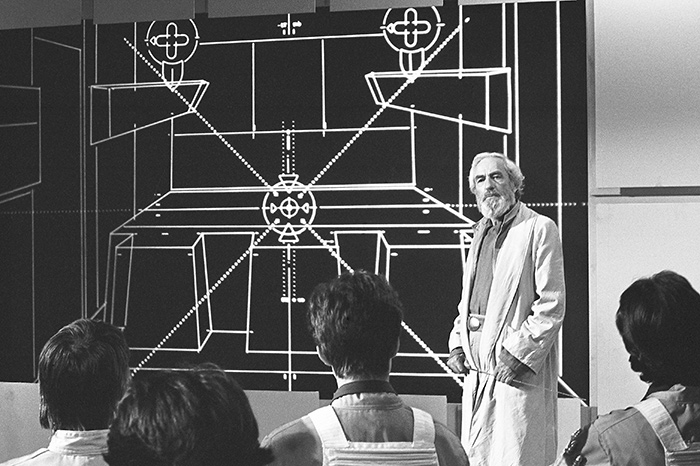

In Chicago, Larry Cuba was also struggling with his deadlines, in his case for the computer animation. “I thought we’d start work in December,” Cuba says, “but the actual contract was not decided on until February, and they said the actual deadline was June 1. So based on the data, I thought we could still make it—but in the middle of April they said, ‘We made a mistake. The shooting schedule just arrived from England, and we noticed that the scene we need your stuff for is May 6. So we actually need it in April for them to prepare over there.’ So I called George and he said, ‘Well, we can change our shooting schedule.’ So they rearranged it for the last day the set was available: May 17—which meant we had to send it on May 6.

“So we went at it. All the shooting was done in the last week in April. But then the hardware just kept breaking down during the crucial weekend. I had even decided on Saturday night that I would call them on Monday and say, ‘I tried but you are going to have to do bluescreen.’ I decided to go to sleep. Usually the computer rooms are air-conditioned to keep the hardware cool, but I figured I’m going to be comfortable, so I turned the air conditioner off. I went to sleep at midnight; at three I woke up and I thought, ‘Well, it’s gotten warmer in here—I’ll try it.’ And the computer ran continuously all day Sunday from then on; it crashed maybe two or three times during the whole day. We were lucky and we got it out on time.”

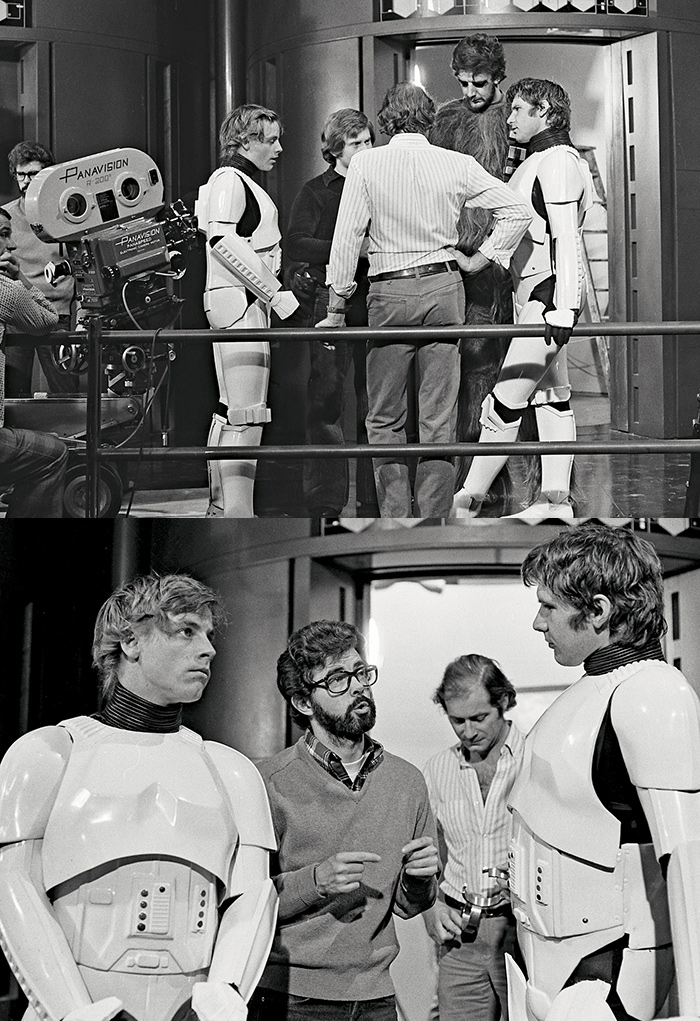

On Stage 2, Lucas watches and advises as Hamill, Ford, and Mayhew await and then board the Death Star elevator.

Back in England the frenetic pace of the shoot, which was now four days behind schedule, was taking its toll on cast and crew. The scope and complexity of the sets were particularly challenging. Production supervisor Robert Watts happened to be interviewed by Charles Lippincott on May 10, 1976, so his words relate exactly what the crew was experiencing: “The biggest problem on this picture is that we have a large number of sets that we shoot on for a comparatively short period of time. So it has been a case of trying to keep up with the set construction. Though we’re employing a large number of laborers, we’re literally only one day ahead on the set construction. People have been working on weekends; people have been working overtime in the evenings to get this thing done. But it’s been necessary, because we couldn’t have kept up without it.”

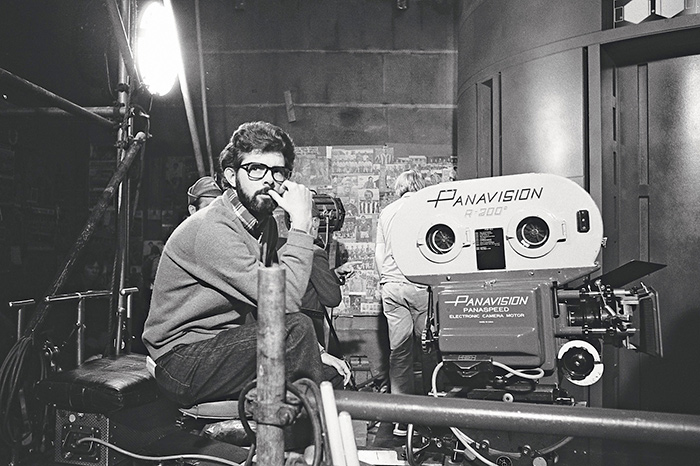

In the middle of all this was Lucas, whose experience on sets up to this point had been dramatically different, because he’d either been on location or on a tiny set on a small sound stage. THX 1138 and American Graffiti had had a total of about 40 people on the payroll, whereas The Star Wars had 950 paid employees, simultaneously working on fairly massive sets within two large studios.

“We’d really be on a set for only about one day,” Lucas says. “We’d finish shooting and then we’d move on to another set; and we’d have to tear down the previous one and build another one right away, because we didn’t have that many sound stages. At EMI there were eight sound stages, but that’s a little better than a week if you’re shooting a set a day. Sometimes we’d put two or three sets on a stage, which would give us that advantage, but no matter how you did it there was a tremendous amount of pressure to get sets finished and redressed. It was really like riding a freight train at about 120 miles per hour and having the guys trying to build the track in front of you as you go.

“One of the results was to make it hard to have complete control over things,” Lucas adds. “I would tell somebody to do something and that somebody would tell somebody else and by the time the guy who was actually nailing the fixture to the wall got the message, it was usually the wrong message. That was not only frustrating for me, it was also frustrating for John Barry. He would bang his head against the wall and say, ‘Why can’t they just do it the way I tell them?’ And that’s what I would say, and we were both in the same fix.”

“George will sometimes tell some carpenter on the floor to change something without going through the chain of command,” Watts says. “But if one thing is changed and it doesn’t go over the production office desk, the ramifications of that one change may affect four different departments. So it should always come through here, which is now happening. But that’s, you know, a minor consideration.”

“You cannot control it, unfortunately,” says Barry, who was interviewed just a week later, on May 17. “You can dictate the letter, but it’s going to come out in somebody else’s handwriting. It’s driving me potty, doing the sets, because it’s so absolutely time-consuming—and even though you work seven days a week, you can’t do everything, but you can’t delegate, either. That’s the director and designer’s problem: Basically, you are dependent on somebody else, because of the time scale. Ironically, the more you do get involved, the more it ends up like a Stanley Kubrick film, taking fourteen months instead of eight weeks. And the sets all are terrific, but nobody notices that the actors are very dull.

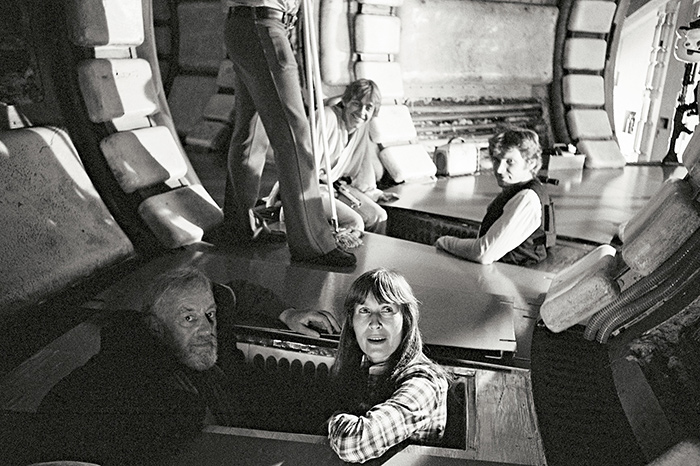

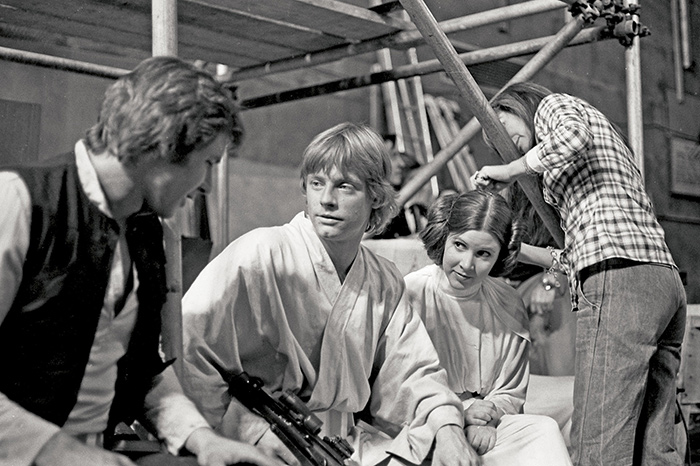

On Stage 9 Guinness, Hamill, Ford, and Daniels quickly ran through several scenes in the Falcon’s main hold.

For Ford, the line, “Kid, I’ve flown from one side of this galaxy to the other …,” perfectly explained his character.

Hamill, on the other hand, complained to Lucas about his line “Gee, it’s lucky you had these compartments” while they were shooting their exit from the smuggling vaults (hair stylist Patricia McDermott). “But George said, ‘Just get in the compartments and do it,’ ” Hamill says. “And he was right.”

“Fortunately, George knows that a lot of things can be changed and altered, and is always ready to discuss it, to come and look at the sets after the rushes,” Barry adds. “We’re always walking around the sets at eight o’clock at night, so nothing’s a horrid surprise when George gets on there in the morning.”

Most of the film’s numerous and rapidly built sets continued to the very outermost edge of the stages, and Lucas would photograph them with two, three, or four cameras. “I shoot fairly rapidly but I pick out shots as I go,” he says. “I like to stand on the set and see the scene take place and decide how I’m going to shoot it. I’ll watch the scene through the camera, move the camera around, watch the scene various ways, and get rough ideas about things. That’s why I use a couple of cameras.”

The combination of the size, number, and resulting costs of the sets, mixed with Lucas’s unorthodox shooting style, turned out to be very confusing for Fox executives and the crew. Both were expecting lots of wide establishing shots of the elaborate sets, whereas Lucas would often start in close, or dispense with more ordinary coverage. “George says he wants to make it look like it was shot on location,” Barry says. “So if you’re shooting on an ordinary suburban street, you don’t do a great big shot of a suburban house, because everybody already knows what it looks like. He wants to give the feeling that everybody knows about Mos Eisley or whatever; he wants a newsreel sort of feeling.”

“There was a lot of negative reaction coming back from England to the US,” Alan Ladd says. “People were saying, ‘We spent all this money on these big, elaborate sets and he’s only shooting a piece of it!’ George wasn’t doing the 360-degree camera angle, exposing the entire set.”

“They wondered when they were going to see more sets,” Lucas says, “but they didn’t really make a big issue out of it. I think Laddie kept things under control, and obviously that’s the office that can come down on you and really cause trouble.”

“Sometimes people get upset because of the way George shoots,” Watts adds. “Maybe he’ll not do a master first or something like that. But it’s his prerogative—because every member of the crew, from the top to the lady who sweeps the offices out, is only here for one reason: and that’s to help George tell a story. That’s my belief. Sometimes you can work with a director and really think you’re getting a lousy picture, and that’s depressing. But that’s not the case here at all. I think that if we can make as good a picture as American Graffiti, then I think we’re in. I wish I had a piece of the action …”

SCS COMP: 65; SCREEN TIME: 60M 01S.

“The prison floor is made up of plastic pallets for fork-lift trucks, which we bought off the shelf,” John Barry notes of the set built on Stage 4.

Hamill’s scene in the prison cell has him, for the first time in the film, speak the name of his character—“I’m Luke Skywalker …”—which had been Starkiller until just a few weeks before.

REPORT NOS. 37–38: TUESDAY, MAY 11–WEDNESDAY, MAY 12, 1976

STAGE 4: INT. DEATH STAR, A42 PART [LEIA’s CELL AND BLACK TORTURE ROBOT]; 89 [LEIA: “AREN’t YOU A LITTLE SHORT FOR A STORMTROOPER?”]; 88 PART [ARRIVAL AT PRISON LEVEL, FIGHT]

Production continued to speed from stage to stage, moving on to the prison cell set, with the help of assistant director Anthony Waye—one of those chosen by Watts and Lucas for his toughness—while the second unit filmed inserts and R2-D2 putting out a fire in the pirate ship hallway.

On Wednesday, May 12, in her prison cell scene with Vader and the torture robot, Fisher

again had to work up fear for someone whom she found not very threatening. “I was

in a little box of a room, so I used the idea of claustrophobia to make it scary,”

she says. “But it was hard to be afraid of Darth Vader. They called him ‘Darth Farmer,’

because David Prowse had this thick Welsh accent, and he couldn’t remember his lines—

I guess I could’ve been afraid of that.”

The morning of the second day on that set, Fisher prepared as she usually did: “Coca-Cola first thing in the morning. I used to sit in the bathtub the night before and go over my lines, like the one in the prison hallway when I would say, “This is some rescue. When you came in here, didn’t you have any plan for getting us out?’ I planned a reading for it. But when I went in the next day to do the scene the entire hallway was blowing up—so there was no other way to do it but, ‘THIS IS SOME RESCUE! WHEN YOU CAME IN HERE …’ After that, I would memorize my lines and wait to see if we were being blown up or not.”

“Carrie is the funniest girl I ever met,” Hamill says. “She makes me laugh, almost always, and she has a great sense of humor about herself. She doesn’t take herself seriously, which would probably be very easy for her to do. I actually didn’t know how the Princess was going to be. I did the whole hologram scene before I even met her. So Carrie comes in and she’s like Carole Lombard: beautiful to look at, but with a sense of humor.”

As a child Fisher used to “read” books before she could actually read the words, making up stories to go along with the cover or illustrations. After progressing through an “Archie and Love comic-books phase,” she became an avid reader of Hemingway, Shakespeare, and Fitzgerald. She would also fake being sick so she could stay at home and watch Andy Griffith, I Love Lucy, The Real McCoys, and old movies on TV.

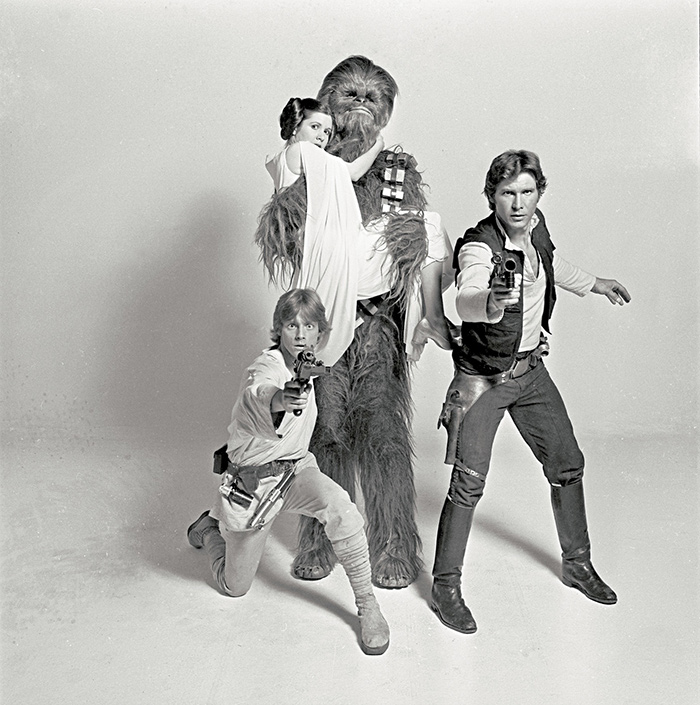

As their scenes together multiplied, Fisher and Hamill were finding a rapport, as were Hamill and Ford. Played as written, they were supposed to simply exit the elevator into the prison area. The day of shooting, however, they ad-libbed, facing the wrong direction when the door opened, to add a comic touch. A few days before, they’d improvised with Peter Mayhew: As they marched down a Death Star corridor, Chewbacca growled at a mouse droid, which, radio-controlled, did an abrupt about-face and scurried in the opposite direction. In short, the actors were creating the all-important chemistry that Lucas had hoped they would. One point that seems to have drawn them all together was Ford’s cabalistic handling of his dialogue.

“I had already been shooting for four weeks, going on five, when Harrison came in,” Hamill says. “He visited the set once and then I went over to his hotel room. We were going to go out and have dinner, and I’m flipping through his copy of the script—and I see lines of his just crossed out completely. He’d written things in the margins, saying the same thing basically, but his way. He had an amazing way of keeping the meaning but doing it in a really unique way for his character. Well, I was … you know, the script was the bible for me. There were lines I just couldn’t say, but I learned to say them. It might have even helped my character, in a way, that sort of stilted dialogue. But I also kind of kicked myself and wished that I had been loose enough to do what Harrison was doing.”

Ford, Hamill, and Fisher on the set.

Hamill, Fisher, Mayhew, and Ford in a publicity shot.

A few of the rigging department crew at Elstree Studios.

“I used to go over lines with Harrison and Mark,” Fisher says. “Harrison would always change his lines. I was very impressed that he could do that. I didn’t know what to do with them. They seemed fine like they were. I was also being agreeable because I kept thinking they were going to realize their mistake soon about hiring me.”

“Mark makes this big point about my changing dialogue,” Ford says, “but I don’t remember really changing that much. I would change the phrasing slightly or put a line or a group of five lines in a different place. But I would usually discuss those with the script girl, rather than George.”

Nevertheless, Hamill seized upon the prison-level scene as an opportunity for some of his own line changes. “When we were bringing in the Wookiee, the guard [Malcolm Tierney] asks, ‘Where are you going with this thing?’ ” Hamill says. “And the line was something like, ‘It’s a prisoner transfer from cell block …’ And then lots of letters and numbers. But I love in-jokes, so I said, ‘This is a prisoner transfer from 1138.’ But George came over and said, ‘Don’t do that.’ But we did four more takes and by the end I was doing it again. I think I did it on the one he printed.”

He did. “Working with actors is like working with any professional,” Lucas says. “All you have to do is explain what you want and help them try to get it. It’s communication more than anything else. There are a lot of theories, but ultimately, at the practical level, it’s just a matter of getting across what you want the character to do. If the part is cast properly and you have a really good actor, he can do it. In terms of changing their lines, well, that’s a matter of letting them have their way. Lots of times actors have very good instincts. They’re thinking about the character a lot more than you are. You’re looking at the whole thing—they’re looking at only that particular person. If they’re uncomfortable or something doesn’t work, it’s usually because there is something wrong with it.

“If I have a disagreement about something with an actor, I’ll do it both ways,” he adds. “I’ll spend the time and money on the set to let him have what he wants, but that’s just a matter of give and take. There are some crazy actors in the world, obviously, but the best thing to do is to avoid them. I only want people who are good, talented, and easy to work with, because life is too short for crazy actors.”

“You like George so much as a person, and feel so at ease with him as a friend, that you want to please him,” Hamill says. “He would never embarrass you or make you feel foolish for trying some things—and I tried really amazing things that were really wrong, thinking back on them. I did have a couple of disagreements with him, not big ones, where he’d say, ‘Well, I don’t think he should do it that way.’ And if George thinks you are wrong, there is no way you can convince him that you are right. He might be open to a hundred thousand ways of doing something, but if you pick the one that he thinks is wrong, there is no way you can show him you’re right.”

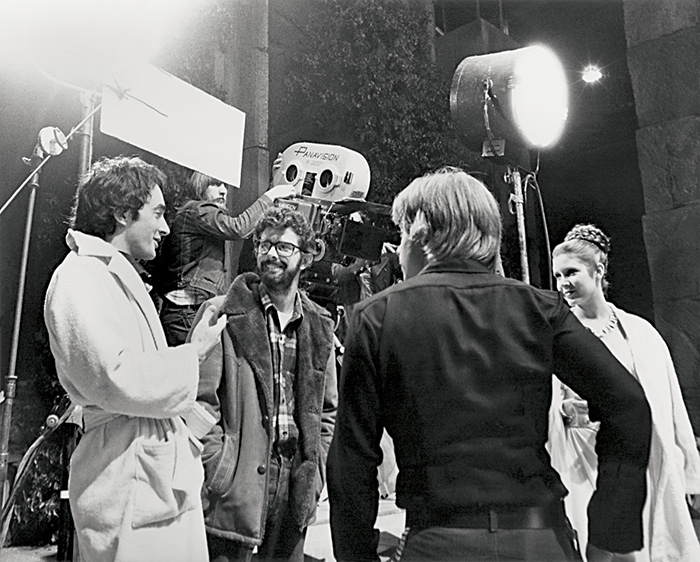

Alan Ladd Jr. and George Lucas at Elstree Studios in late April/early May 1976.

Ladd with an unidentified crew member.

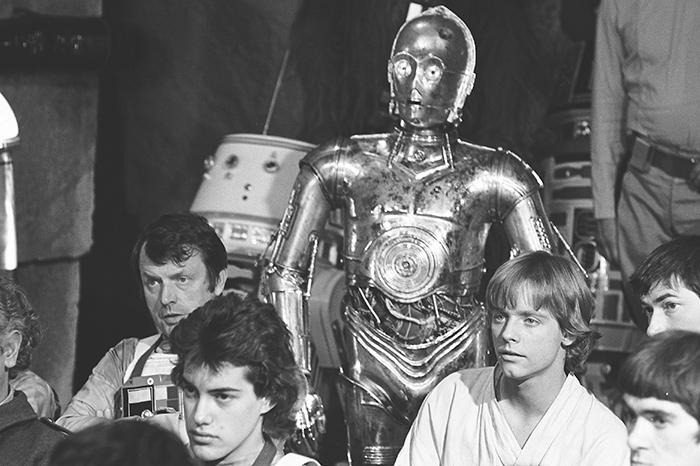

The Rebel briefing and war room sets occupied the same stage at Shepperton. Alex McCrindle is General Dodonna, next to Fisher as Leia.

On display are the computer graphics hurriedly created by Larry Cuba for a grand total of $10,200.

While the on-set camaraderie between the actors and their director increased, the department heads were having a more difficult time of it. “John Barry and Gil Taylor didn’t get along very well,” Kurtz says. “They really didn’t talk much, unless I forced them to by having a meeting. There were some problems John created for Gil by not allowing enough room for lighting the sets, and Gil created a lot of problems for John.”

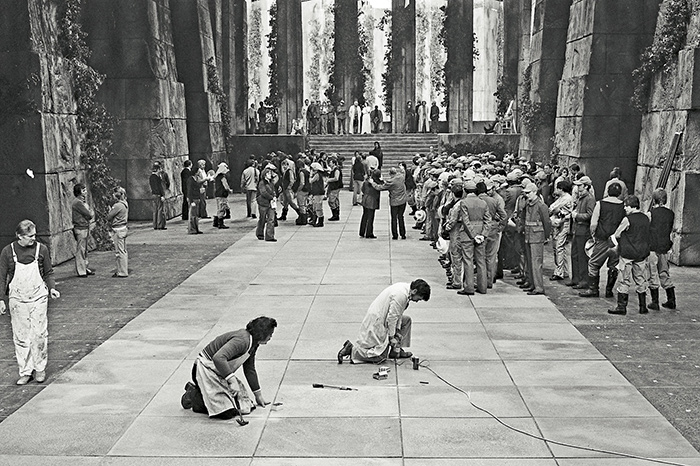

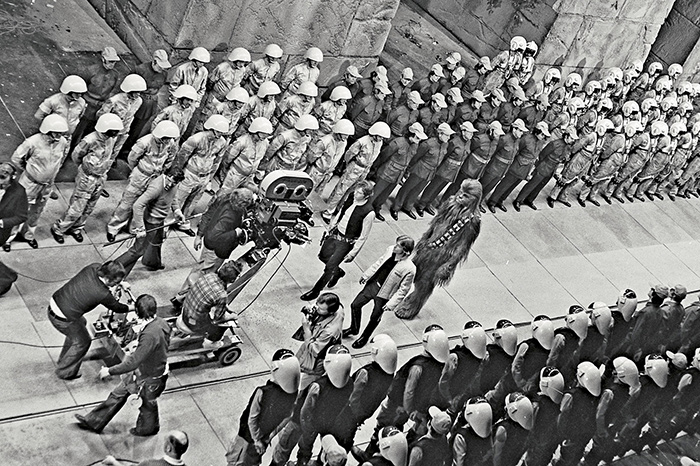

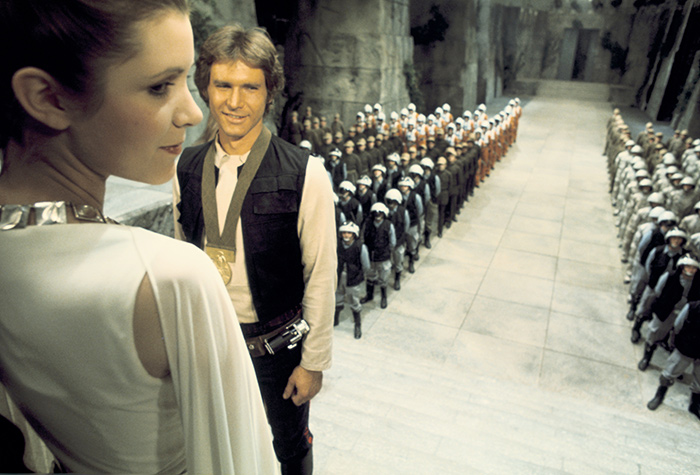

At Shepperton Studios extras line up for the throne room scene.

Technicians put the finishing touches on the set of the Massassi temple that had been budgeted at £1,500 ($3,035).

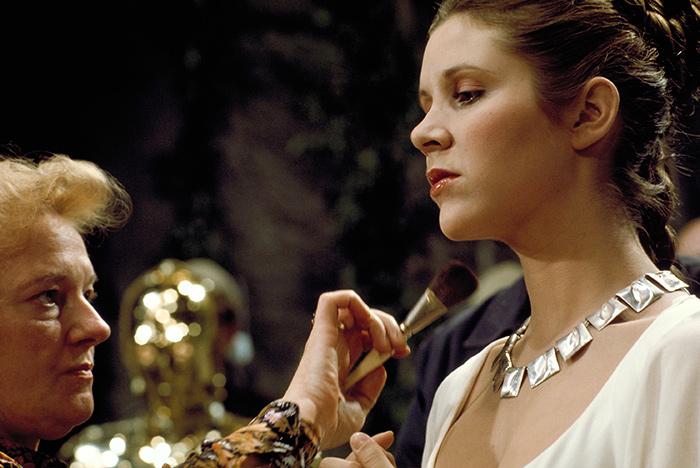

Stuart Freeborn helps Peter Mayhew into costume.

One particular problem was the color of the Death Star walls. “I always wanted to use a navy-blue steel color,” Barry says. “We went through various tests with that, but it does seem to have been too dark, as events have turned out. It didn’t seem to be able to light up enough in the Death Star conference room. But I have changed it now to a lighter gray. I also gave Gil a bad time because it’s really tough to light a set that’s that dark with characters in it who are wearing either black or white. The light panels were metal, and they started to distort because Gil had to use, and very wisely I might add, thousands of photo floods. But I learned long ago that if you give the lighting cameraman an extremely bad time, it makes the lighting very interesting.”

“When you get a person like John Barry,” John Stears explains, “who is really so interested in the artistic merits of the film, it’s very, very difficult—because he builds sets that don’t work for us. We’ve had problems two or three times now where things don’t work for the lighting cameraman. Gil’s had awful problems; I’ve had several problems, too. But it’s one of those things you have to get around.”

Unfortunately, Taylor became the locus of more bad feelings, a result of the fallout after Alan Ladd came over to see the dailies in late April and early May. “Up until that point I had been getting very negative feedback from London about the picture,” Ladd says. “And the picture was escalating in cost, so I thought I’d go see for myself.”

Ladd’s trip was primarily to placate certain executives at Fox who were in an uproar. “I remember people saying, ‘How can this be?! Star Wars is going to cost us over $10 million—how are we ever going to get our money back?!’ ” Warren Hellman says. Ladd was also interested in shoring up his own base, as rumors were circulating that he would soon be fired due to the horrendous fiasco of a film he had championed called The Blue Bird, released on April 6, which would eventually be referred to as “without a doubt the turkey of the decade.”

As Lucas was busy filming, Ladd and other visiting Fox executives were shown film footage without the director’s presence. “I was warned up front that it was a very rough assembly, and that they were quite unhappy with the editor,” Ladd continues. “The picture started, and all I could say was, ‘That’s interesting; it looks good,’ and so forth. But, and I never said this to George, my real reaction was: utter and complete panic.

“I didn’t sleep that night. But the next day I spoke to George, and when I heard specifically what his concerns were, and how things should be changed, I must say I lost the anxiety about it. Had George said, Didn’t you love it? I would have been very scared and very nervous. But he said, ‘This is not what I want and this is not what it’s going to look like.’ He explained that he hadn’t even seen a lot of the footage himself yet.”

Lucas also allayed the studio’s anxiety about the end battle. The last two drafts of the script described each shot in so much detail that it had covered a lot of pages—and pages meant screen time, which meant money. “There was a lot of concern about the page count, people saying the picture would run three hours,” Ladd adds. “But George told me in London that the battle sequence was timed out completely, and that the whole movie would not go over something like two-ten.”

After Ladd returned to the States to give his report, another Fox executive carried out an end run in London—again influenced by the company’s experience with Lucky Lady. “It was after Laddie and those guys came over and looked at the first few weeks of dailies,” Lucas says. “They said it all looked fuzzy. I think part of it was an overreaction on their part to Lucky Lady, which had not done well. It had that gauzy look, and they were afraid that that was why it wasn’t a hit. So I think Peter Beale told Gil, without telling me, to stop using the gauze, which was unfortunate. Because a day later I noticed a difference in dailies, so I asked Gil, ‘Did you have gauze on that?’ And he said, ‘No, no, I think on the Death Star we shouldn’t have gauze ’cause I think it’s too black,’ and he gave me all these excuses. Then I found out a few minutes later that the studio had told him not to do it.”

On Shepperton’s H Stage, crew make ready the floor of the throne room for the scene in which Mayhew, Hamill, and Ford walk down the aisle to the dais.

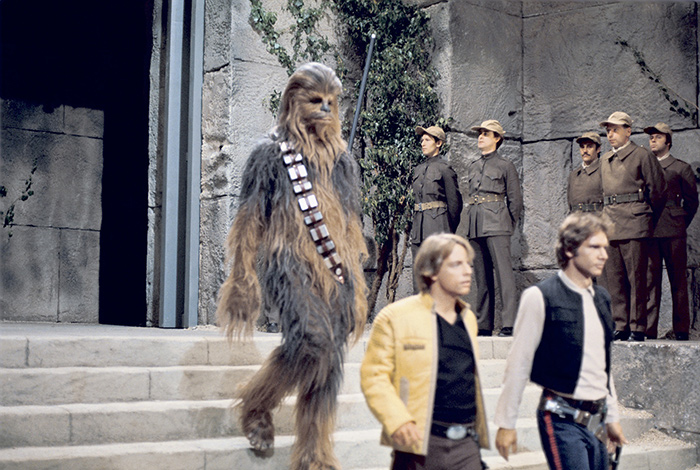

Mayhew, Hamill, and Ford walk down the aisle to the dais, with extras in the background clothed in Mollo’s last-minute find at Berman’s: olive green US Marine outfits—with buttons.

Already unhappy because Taylor hadn’t been giving him the documentary style of lighting he’d requested, Lucas, who had been working more with the camera operator on the framing of shots and movement, felt understandably betrayed by both his DP and the studio. The production was five days over, R2-D2 still wasn’t working properly, costs were escalating, and the pace was not about to let up.

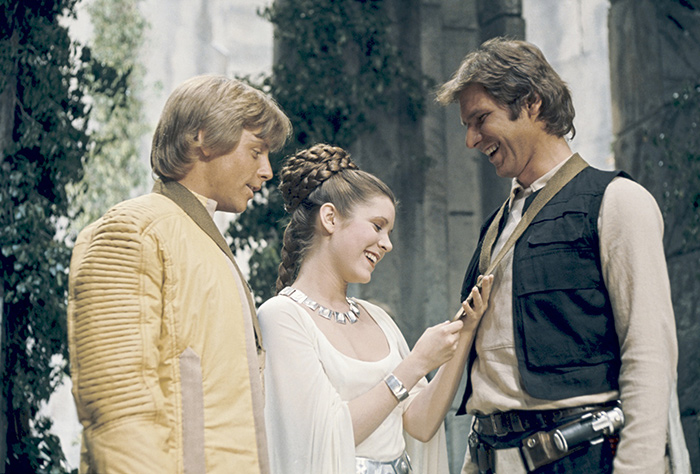

The award ceremony scene.

Daniels, Lucas, Hamill, and Fisher sharing a light behind-the-scenes moment.

SCS COMP: 69; SCREEN TIME: 62M 43S.

REPORT NOS. 39–47: THURSDAY, MAY 13–TUESDAY, MAY 18, 1976

SHEPPERTON STUDIOS, H STAGE: INT. MASSASSI OUTPOST, THRONE ROOM, SC: 252 [CELEBRATION]; INT. MASSASSI WAR ROOM; SCS: 135 [DEATH STAR ATTACK BRIEFING]; 137 [DEATH STAR ARRIVES]; 190, ETC. [LISTENING/REACTING TO BATTLE]

Production traveled across London to film on Shepperton Studio’s H Stage from May 13 to 18. Although it was an enormous cavern, Lucas was going to have to carefully film angles that would make maximum use of his extras. Additional Rebel personnel and the missing parts of the set would be created later with a matte painting. The extras he did have needed to be briefed as to the story, which Hamill, who by this time was thoroughly invested in the movie, took upon himself. Clothing them was John Mollo’s job.

“That scene wasn’t in our budget,” Mollo says. “Someone came in and said, ‘Of course, you realize there are 250 extras in it.’ So we asked George and he said it was more like four hundred, so we really had to make do. Nothing was made at all; it was all stock items. We took our gray Rebel combat jackets and our pilot outfits, and we added funny caps. At Berman’s, in boxes, we found something like two hundred US Marine olive-green stand-ups, which we left well at the back because they had buttons on them. We also found two hundred French Foreign Legion costumes, khaki jobs with collars, so we added hats, scarves, and things. For the Rebel generals, George came in with a still from Once Upon a Time in the West, where they were all striding through the dust in Rangoon coats. Gary came in with a khaki jacket with leather patches and a bit of metal hanging on it. One of the art directors wanted an American cavalry shirt…

“I think we asked George, ‘Is Luke wearing his flying suit in his last scene, or does he go back to his own clothes?’ ” Mollo continues. “And George said, ‘No, I think he ought to look a bit more like Han.’ It was a very last-minute thing, but we concocted an outfit like Han’s in different colors.”

Carrie Fisher wore the same white dress, but her hair was changed to what was referred to as the “hot plate special”—an arrangement dreamed up by Lucas and Pat McDermott. Although suffering from a cold, Anthony Daniels took the stage in spruced-up attire. “All through the film I was covered in grime,” he says, “but for this shot, I am absolutely gleaming, which of course gave all the camera people problems.”

Because the robots couldn’t climb the stairs with the three heroes, they were placed with the Princess at the top—which was still a perilous place. “I could come down stairs purely by force of gravity,” Daniels says, “and nearly had a couple of nasty accidents where I miscounted the steps; once I set off there was no stopping me until I reached the bottom. When Luke comes up to get his prize, I played the whole thing a bit like a Jewish mama seeing her son at his bar mitzvah.”

The scheduling of the award ceremony couldn’t have been better. The actors had really gotten to know one another by this time, and their camaraderie spilled over and into the scene, with Fisher’s infectious humor and smile mirrored by Ford and Hamill—and caught forever on film.

SCS COMP: 78; SCREEN TIME: 69M 41S.