REPORT NOS. 43–51: WEDNESDAY, MAY 19–TUESDAY, JUNE 1, 1976

EMI STUDIOS, STAGE 4: INT. DEATH STAR PRISON CORRIDOR, SCS: 88 PART; 91 [SOLO: “MAYBE YOU’d PREFER IT BACK IN YOUR CELL?”]; 96 [LEIA BLOWS OPEN GARBAGE CHUTE]; 88A (EXTRA SC: LUKE IN CORRIDOR)

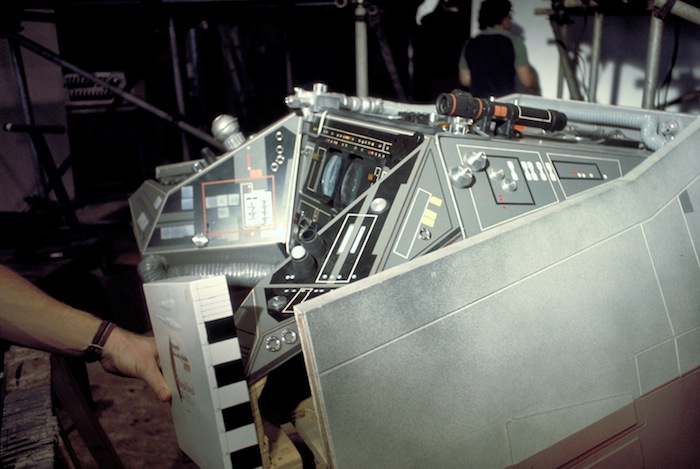

STAGE 8: INT. PIRATE STARSHIP COCKPIT, SCS: 60 PT. & 62 [SOLO: “WATCH YOUR MOUTH, KID, OR YOU’ll FIND YOURSELF FLOATING HOME”]; A67 [COMING OUT OF HYPERSPACE]; 73 [FALCON SPOTS TIE FIGHTER]; A74 [LUKE: “HE’s HEADING FOR THAT SMALL MOON”]; C74 [OBI-WAN: “THAT’s NO MOON …”]

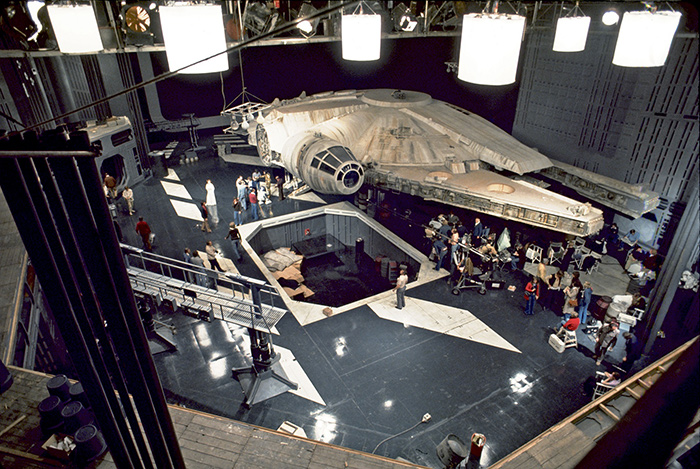

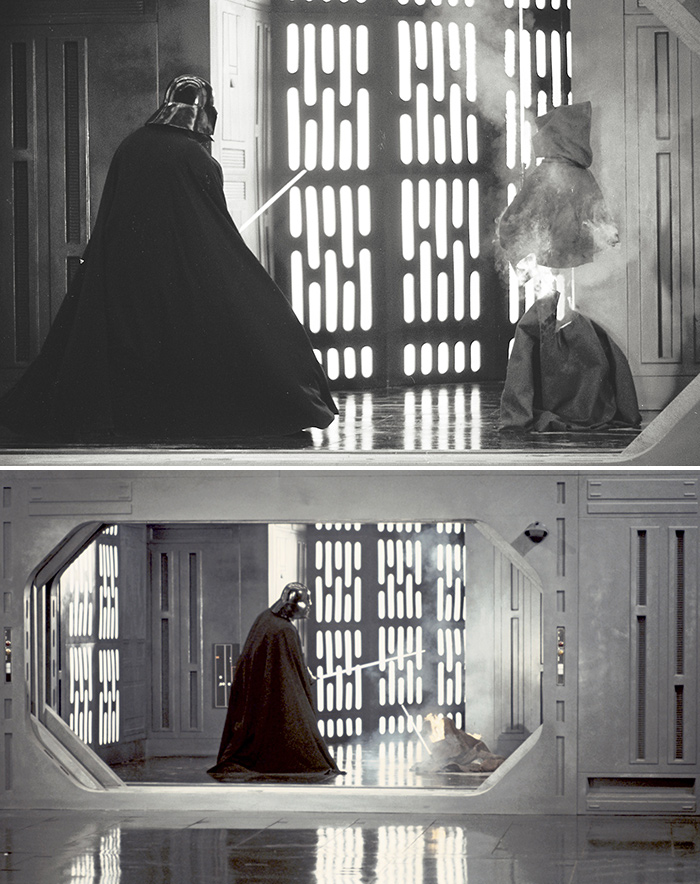

STAGE 3: INT. DEATH STAR, MAIN FORWARD BAY; SCS: 77 [OFFICER REPORTS FALCON IS EMPTY]; 81 [STORMTROOPER CARRIES SCANNER EQUIPMENT ONTO FALCON]; A101, A102–04 PART [R2-D2 PLUGS IN, C-3PO TALKS WITH LUKE]; 117 PART [VADER AND OBI-WAN FIGHT; OBI-WAN IS CUT DOWN; HEROES ESCAPE]; 116 PART [VADER: “WE MEET AGAIN AT LAST”]

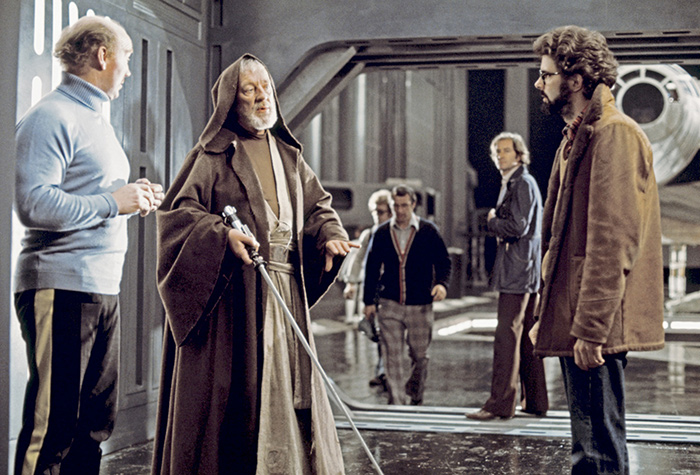

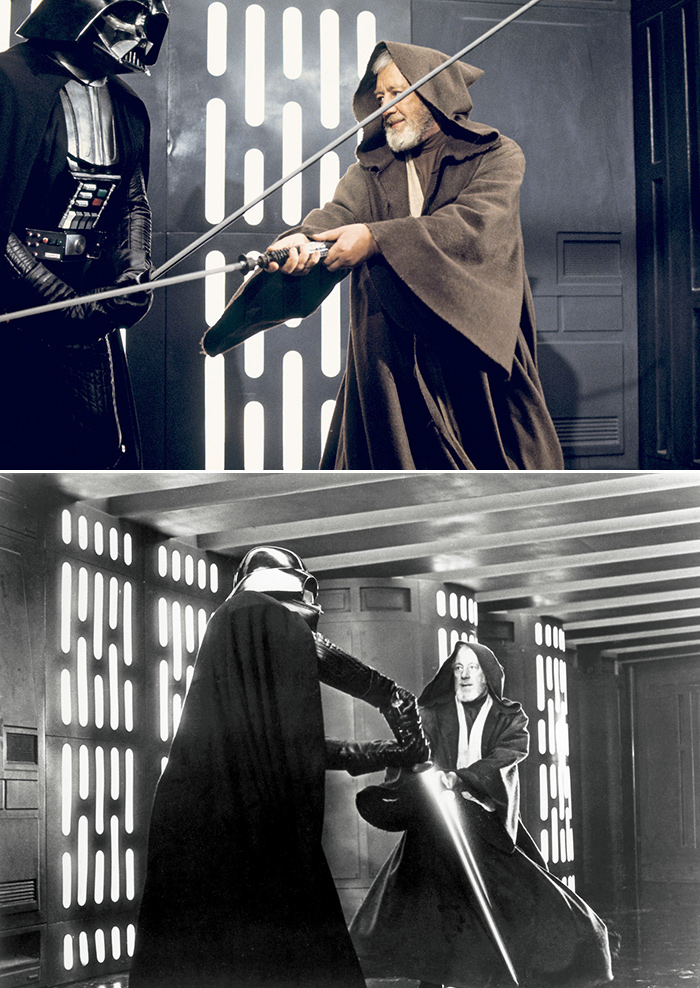

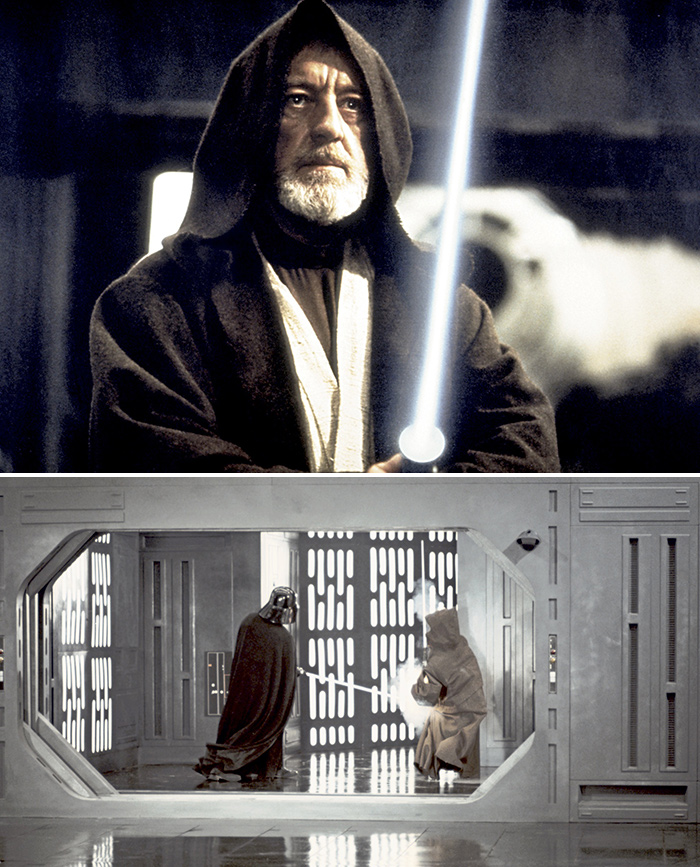

For logistical reasons, the fight between Obi-Wan and Vader was filmed first, for three days beginning on May 27, before their actual meeting was shot on June 1. Stunt coordinator Peter Diamond had started thinking about this duel the day he had met the director. “George said, ‘I’ve got these laser swords—I don’t want broadswords and I don’t want fencing. I want it somewhere in between,’ ” Diamond says. “So I had to create a style that was unique.”

He trained Prowse and Guinness in that special style, but the day of the shoot things went a bit slowly. “It’s a natural tendency when you are cutting at someone’s head to bring it down as hard as you can,” Diamond says. “The fight took slightly longer to shoot than anticipated because of that problem … and David Prowse is such a heavy-handed man, every time they touched swords, the blades kept breaking.”

A few days before the duel, on May 17, Lippincott had interviewed John Barry. One lingering aspect of the shoot that hadn’t yet been tackled was bothering the production designer. “Front projection gives us enormous problems,” he says. “We can’t build front projection to full size, because that’ll push us too far away from the screen—and you’ve got to keep the screen fairly tight up behind the cockpit, otherwise we get this terrible fringing problem. It really is a perfect case of the cart before the horse. It’s really going to cause quite a bit of problems, for George, ultimately.”

Barry wasn’t alone in his apprehension, so, on May 27, the second unit started front projection tests on Stage 8 using an extra in the pirate ship cockpit after the principals had been filmed. “I was worried about the approach to the Death Star sequence,” Kurtz says. “We desperately needed the plates, but we weren’t getting them. And the shots that ILM did send were not right. I said we needed long shots of the approach, and they were giving us short pieces for front projection. They kept saying that we’d have to cut away. Instead, we spliced them all together to make them long enough.”

Back at ILM, there was disagreement as to the quality and quantity of what was being delivered. “We delivered sixty plates; we thought they would work,” says Robbie Blalack.

“When they reached the point in live-action shooting in England when they needed the process plates, we didn’t have ’em,” Dykstra says.

Once everyone saw the second-unit experimental footage, however, the verdict was clear. “We saw the tests as they came back and there were a lot of problems,” Blalack admits. “Problems of focus in the process rig in England, some problems of contrast coming from the way we were lighting the ships on our end, the way we were compositing them. In total, it simply wasn’t working.”

“I don’t know who the technician was and I don’t know what kind of problems he ran up against while he was doing it, but it didn’t appear to be usable,” says Dykstra, who, in retrospect, saw it as a flawed concept—trying to time an actor’s performance to perhaps only a few seconds of pre-filmed footage—and he felt somewhat responsible. “That’s real hard, right: You cue the actor and he looks up and he can’t see anything but gray and he’s only got 60 frames to get his line out with feeling. It’s pure luck for him to hit that timing. You can burn film for weeks like that, so that was ridiculous, and it didn’t work. I didn’t foresee that problem. There was no talent in that because I didn’t have any consideration of what they were really trying to do, so I got busted for that one. It was our fault that they didn’t use the front projection. It was another moment for which I felt very bad about things.”

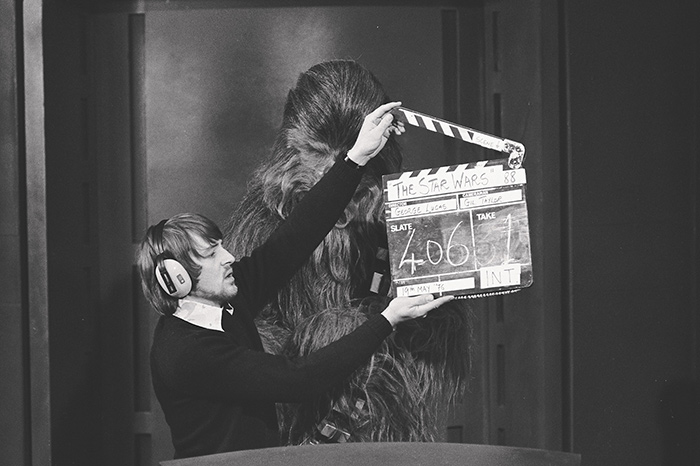

On May 19 cast and crew returned to film more of the prison shootout.

The slate for that day, Take 1.

“When we were wearing the stormtrooper uniforms, you couldn’t sit down,” Mark Hamill

says. “They built us some sawhorses to sit on and that’s the most we could rest all

day. It was terrible. You get panicky inside those helmets. You can see the inside

of the helmet and it’s all sickly green, plus you’ve got wax in your ears, because

of the explosions, and you just feel eerie. I only once freaked out and said, ‘Get

me outta here!’ It really was uncomfortable.”

It was also another setback for Lucas and his crew members, who, according to the progress reports, were increasingly ill and having physical mishaps, from principals to stagehands. They were nine days over, and an essential part of the plan had simply disintegrated. Things also came to a head with editor John Jympson, whom Lucas dismissed about halfway through production.

“I make virtually all the explosive charges,” John Stears says, “which is highly illegal and highly irregular—unless you have a manufacturing license, which is dreadfully impossible to get. You need about a hundred acres and various buildings about fifty yards apart. But the authorities know we do all this here and that we’ve got it under control.”

“Unfortunately, it didn’t work out,” Lucas says. “It’s very hard when you are hiring people to know if they are going to mesh with you and if you are going to get what you want. In the end, I don’t think he fully understood the movie and what I was trying to do. I shoot in a very peculiar way, in a documentary style, and it takes a lot of hard editing to make it work.

“I got rid of some people here and there, but it is a very frustrating and unhappy experience doing that,” he adds. “I realized why directors are such horrible people, in a way, because you want things to be right, and people will just not listen to you and there is no time to be nice to people, no time to be delicate.”

SCS COMP: 98; SCREEN TIME: 79M 18S.

REPORT NOS. 52–62: WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2–WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 1976

STAGE 2: DEATH STAR COMMAND OFFICE; 82 PT [LUKE CONVINCES HAN TO HELP RESCUE LEIA]; 94 [C-3PO TALKS WITH LUKE DURING PRISON BATTLE]; 99 PART [DROIDS PRETEND THEY’d BEEN TAKEN PRISONER]

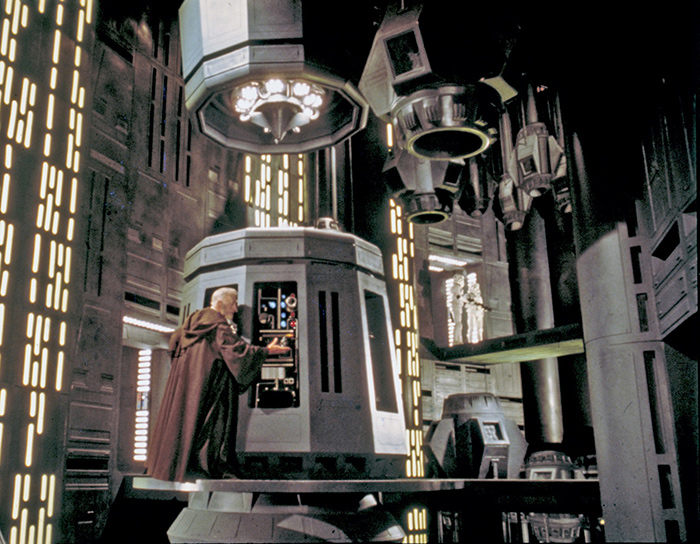

STAGE 2: INT. POWER TRENCH; A105 PART [OBI-WAN SHUTS OFF THE TRACTOR BEAM]

STAGE 8: INT. SANDCRAWLER; 20 [C-3PO AND R2-D2 ARE REUNITED]

SHEPPERTON STUDIOS

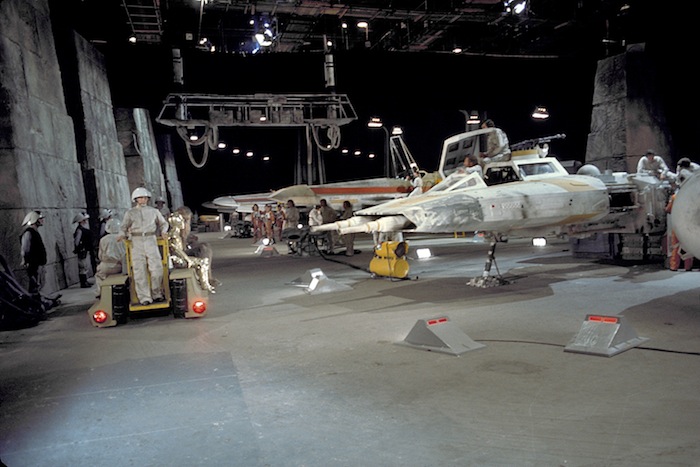

H STAGE: INT. MASSASSI MAIN HANGAR DECK; 136 PART [LUKE REPROACHES HAN]; A132 [HEROES WELCOMED IN CRUMBLING TEMPLE]; 251 [LUKE RETURNS WITH R2]

EMI: STAGE 8—INT. PIRATE STARSHIP; 62 PT RETAKE, A67–E74 RETAKE

“I did say some rubbish to Alec once in the control room because I couldn’t think of the right words,” Anthony Daniels says of their scene in the Death Star. “Rather than screw up the tape, I mumbled. He never batted an eyelid and just carried on. Of course, that takes his kind of skill.”

After Guinness as Obi-Wan left to disengage the tractor beam, on June 2, Hamill, Ford, Daniels, Mayhew, and Kenny Baker completed the scene in which they plot out their ad hoc strategy to rescue the Princess. “Occasionally, I would stop like a real actor and deliver a line absolutely still, like ‘the Princess is going to be terminated,’ ” Daniels says. “You can’t fool about with that line because it is really quite serious. What George instantly spotted was that I only existed when I moved. If I didn’t move, the voice could be coming from anywhere. So I very carefully had to think out how to move as I spoke, to speak the lines with my head, physically.”

The physical side of the robot costume was not improving for the walled-up thespian: Numerous progress reports attest to his continuing discomfort, chafing, and skin irritation. “There was a very strange system of filming, which did very much get on my nerves,” Daniels says. “It took a half hour for me to get dressed up in this thing for the master shot. Then, generally, we’d do everybody else’s ones and twos and close-ups, and then we’d get to me. But toward the end of the film, I couldn’t bear the costume any longer. I’d take it off as soon as I finished a shot, which meant wasting a lot of their time because I’d have to get dressed again. And they never got on to the fact that if I’d been allowed to do all my scenes at once, it wouldn’t have taken nearly as long.”

Daniels’s partial solution was to dress only as much as was needed for the shot. “I would, whenever possible, look through the viewfinder in the camera and discover how much of me was visible,” he explains. “Believe me, if you see just my arm or just my head and shoulders, that’s all I’m wearing in that scene. There is a magical shot in the control room where you see just my hand come into frame and pick up a comlink. But it still took about twenty attempts to do that; they had to put a sticky pad in the palm of my hand. Then I had to watch very carefully out of camera, watch this sticky pad come somewhere near, and then close up, because my hands were hit and miss. Every day was a new experience.”

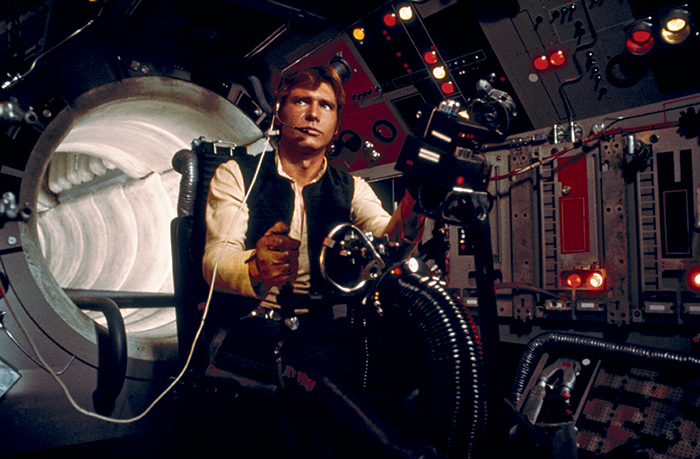

Although quite far apart in the script continuity, nearly all the scenes in the Falcon cockpit were filmed one after the other on Stage 8 late in May and mid-June.

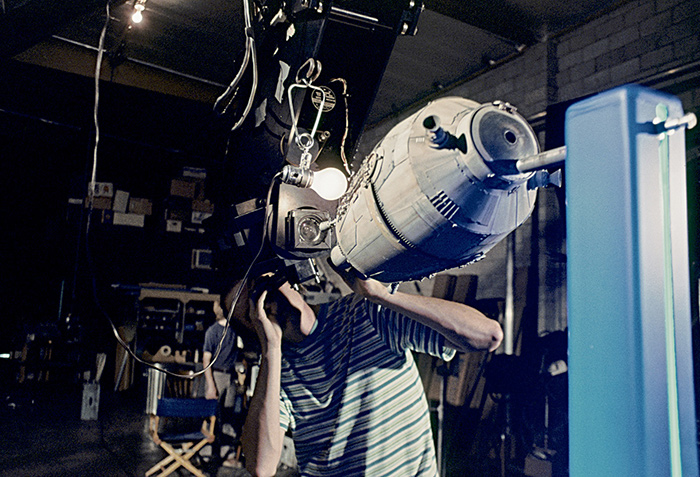

Lucas’s experiences with the robots, however, had become maddeningly similar. “See-Threepio hasn’t been fixed, and neither has Artoo-Detoo,” he says. “Artoo cost us at least a week just because his head wouldn’t work. It just wasn’t well designed and it was not that well executed in the end. I said I want those heads to work, to turn, and we gave them a lot of time and put on more people during production toward the end when we were really using them—and they never worked.”

“There was a problem with Chewbacca’s eyes,” Stuart Freeborn says, listing another headache. They would separate from the hair on the inside and look as if they were separate from the mask. “It’s quite a problem, and really we haven’t got a 100 percent answer to it, and we never will.”

While all of these irritations persisted, the solution to the front projection shots was to opt for bluescreen instead. New plans and budget estimates were made, and Dykstra, Edlund, and Blalack were scheduled for a trip to Elstree. “Everyone was very clear that if photography in England of the actors against the bluescreen, which was to be shot in VistaVision, wasn’t correctly lit, then we were going to have to do a salvage job on top of our normal workload,” Blalack says.

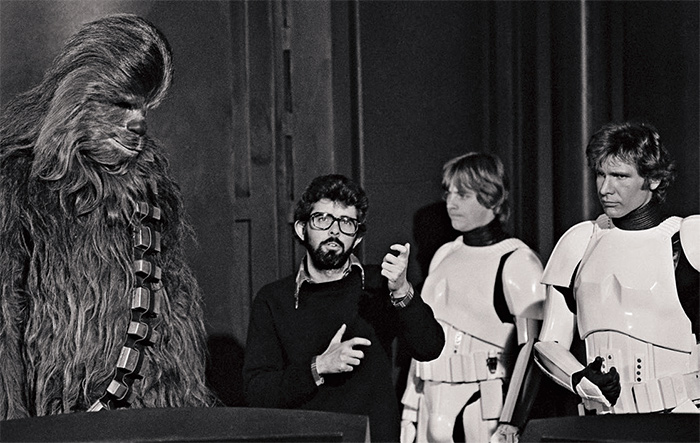

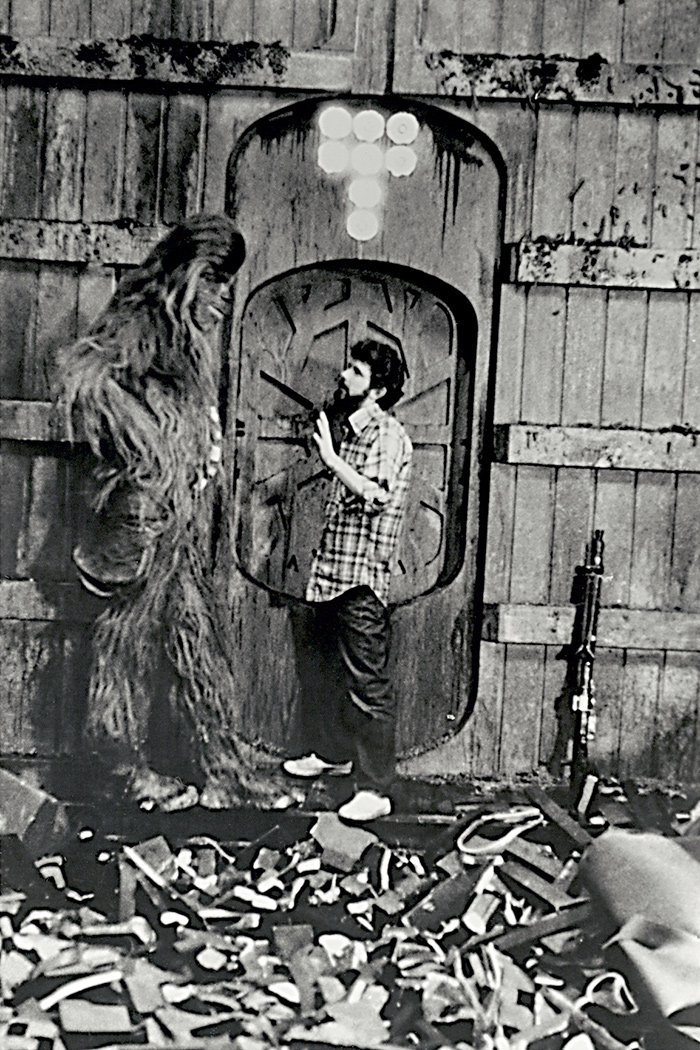

On Stage 3 in mid-May several scenes were shot with the half-Falcon: the arrival of the stormtroopers via the elevator and the shootout (—with sandbags in the elevator shaft). Stunt coordinator Peter Diamond, Guinness, and Lucas discuss Obi-Wan’s duel with Vader in the forward bay on the same stage. Following two pages: Lucas demonstrates to Guinness how to surrender himself to the Force, and the scene is shot with a special effects rig standing in for the departed Jedi Knight.

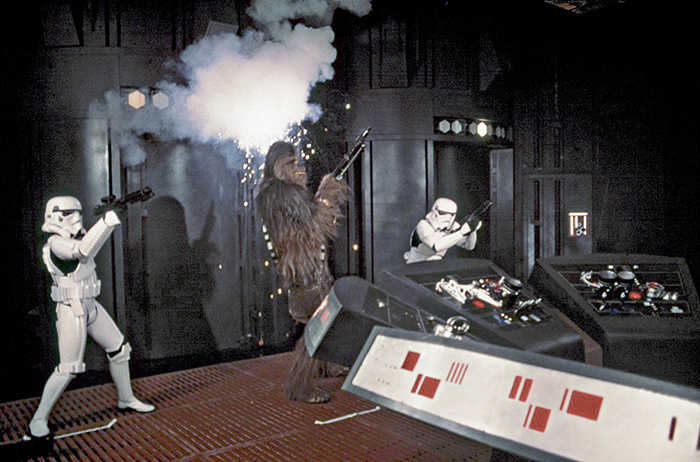

Printed dailies from June 1, 1976, of the Death Star hangar shootout. Several shots

are filmed with three cameras for maximum coverage so Lucas will have lots of choices

while putting the sequence together in editorial during postproduction. (Again, colored

slugs indicate film taken out and used in actual edits.)

(1:29)

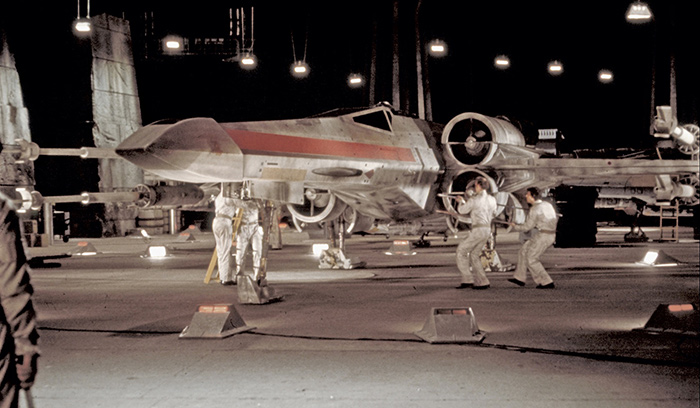

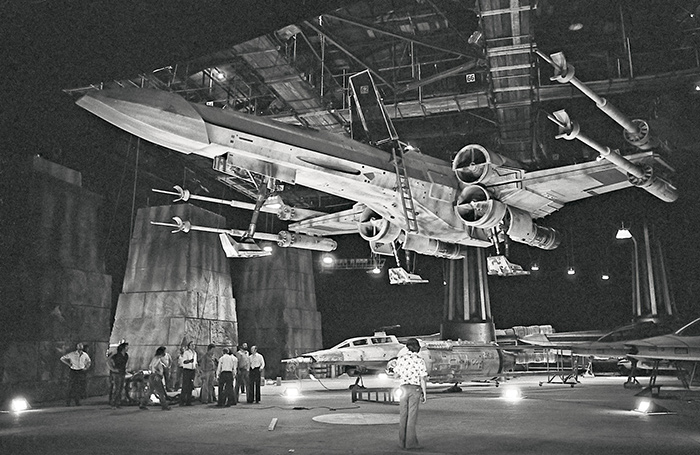

From June 9 to 14 production moved back to Shepperton Studios, where the throne room had been converted to the giant Rebel hangar. “We changed that in maybe three or four days,” John Barry says. “They were both enormous sets, but they’d been built on huge wheeled units, forty feet tall. We had trucks lug them into place, and then George came back again.”

As the earlier conversation between Taylor and Lucas had suggested, H Stage was too small for the hangar, which was supposed to be hundreds of square feet—as big as a real one. Attempts had been made to rent a genuine hangar, but permission to film there proved unattainable. Instead they had to use light and magic. “The sound stage at Shepperton, although it’s 250 feet long, is a little bit small for the Massassi hangar,” Barry says. “So the back half of that set is all in perspective, where the lights go away on the back of the runway. Although they are good old-fashioned tricks that they’ve used all the way through things like Gone with the Wind, it does limit the director. And people don’t like that, which is why those tricks are unpopular.”

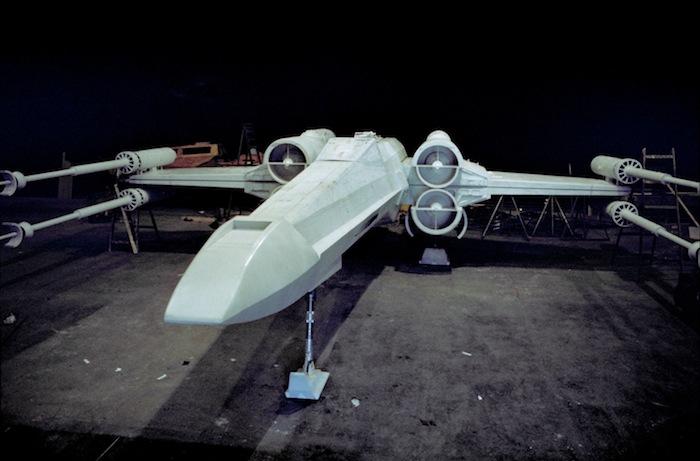

Another trick of the trade included using painted cutouts for the starfighters in the background, as well as filming the two real ships that they’d built in such a manner that they could be multiplied in postproduction. But even the real ships created difficulties. “We got the guy into the X-fighter and the hydraulics brought down the canopy,” Barry explains. “That was great. It closed. But then we couldn’t get it open again. We were all struggling with it—but we had to drill a hole, finally, in order to get him a screwdriver so that he could let himself out. That’s moviemaking, of course.

A printed daily of Ben’s duel with Darth Vader (with Prowse speaking Vader’s lines).

(0:27)

“When the X-fighter takes off and it goes up in the air, there was a lot of fuss about it,” he adds. “People were saying, ‘We can’t get a crane in here and we can’t do this and that.’ So I said, ‘I’ll tell you what: Get one of those gigantic cranes.’ So we had a huge crane outside the biggest stage in Europe, way over the top, and we hacked a little hole in the roof, and the wire came right down through the roof and just lifted the ship up.”

Back at EMI on Guinness’s last day, June 16, the first unit filmed a retake in the pirate ship hallway. It was during this sequence that the actor felt his skill at one moment sagged. When the planet Alderaan blows up, Obi-Wan reels backward and clutches his forehead—“an unpardonable cliché” in Guinness’s opinion. “I still go hot and cold when I think of that scene,” he says.

His own criticisms notwithstanding, Guinness’s performance still stands today as part of the essential charisma that was found during filming—something the other actors were well aware of at the time. “He was the strongest, most solid thing,” Hamill says. “From the very first day he worked, he just had something there. You could see it. A lot of times you couldn’t see it on the set, but when the film was developed, you’d say, ‘I didn’t know that was going on.’ There was just an aura. I think he was playing a wizard, but he had magic all of the time.”

One evening after the day’s filming, Guinness, Fisher, Hamill, and some others went out and got to know each other a little better. “He was funny the night he took us out to that Greek restaurant for dancing, Carrie and all those people,” Hamill remembers. “The owner came out with his daughters and taught us Greek dancing, and we rolled up our pants. Alec has a really whimsical sense of humor. It doesn’t come out all of the time, but in spending a long time with him, I found out that he’s real funny. He was real funny that night. He talked about experiences, and so forth, but if you ask him about what he thought about winning an Oscar, he’s more thrilled at getting nominated for his screenplay The Horse’s Mouth [1958]. That was much more important to him.”

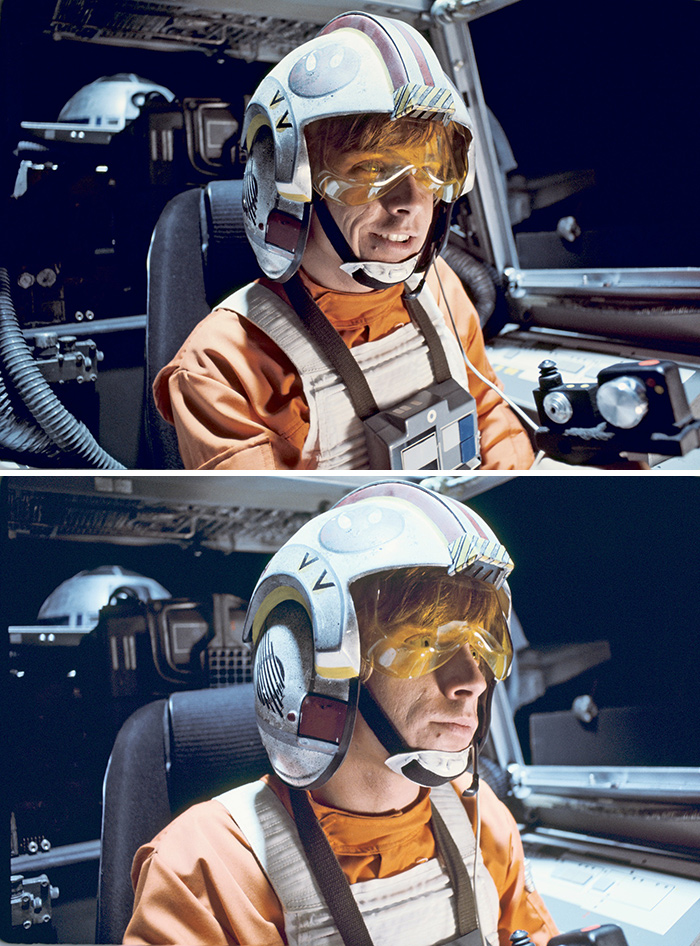

Mark Hamill interviewed during principal photography at Elstree by Gary Kurtz (off

screen).

(1:50)

Sir Alec Guinness.

“I gather he displayed his real personality to much greater effect than I ever saw,” Ford says. “Got real drunk and started dancing around with his pants rolled up. But I never saw him that loose. He revealed his personality to me by doing things like trying to find me a place to live on one day’s acquaintanceship.”

“Good actors really bring you something, and that is especially true with Alec Guinness,” Lucas says, “who I thought was a good actor like everyone else. But after working with him I was staggered that he was such a creative and disciplined person.”

SCS COMP: 112; SCREEN TIME: 92M 30S.

In the Death Star command office, Ben leaves on his mission (with Larry Cuba’s computer graphics in the background).

Luke then convinces Han to go on a more spontaneous adventure to rescue the Princess.

When the robots are discovered, Daniels had to shoot an insert of his robot hand picking up the comm unit—a shot that proved quite difficult to accomplish.

Printed dailies from the Death Star command office scene with Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca

speaking the Wookiee’s lines in English.

(0:33)

John Barry came up with the idea of putting a giant crane outside the studio, whose hook could descend through a hole cut in the sound-stage roof in order to lift up the X-wing so it would look like it was flying.

Various moments from filming on the rebel hangar set, including an unpainted and then painted X-wing life-sized prop.

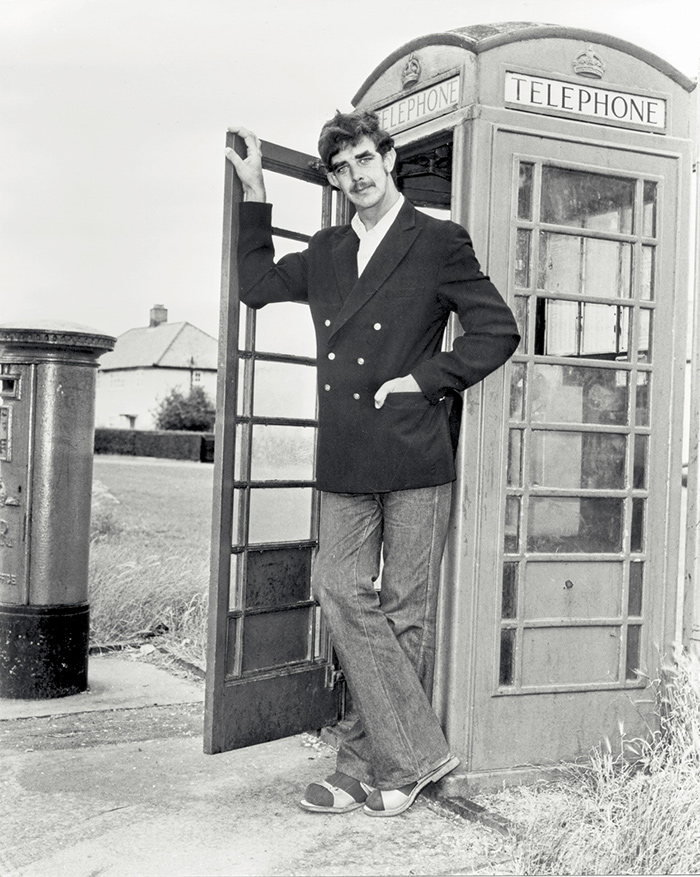

Back at Shepperton Studios, Hamill suited up in Rebel pilot gear.

Others also suited up in the dressing room.

Lucas and company next to the full-sized X-wing.

REPORT NOS. 63–70: THURSDAY, JUNE 17–MONDAY, JUNE 28, 1976

STAGE 8: INT. PIRATE SHIP HALLWAY AND COCKPIT, SCS: A125 PT [HAN: “NOT A BAD BIT OF RESCUING”]; C120 PT & C121 PT [FALCON/TIES FIGHT]; 118 PT [SOLO: “I HOPE THAT OLD MAN MANAGED TO KNOCK OUT THAT TRACTOR BEAM …”]; 239 PT [SOLO: “YOU’re ALL CLEAR, KID”]; 245 PT [SOLO: “GOOD SHOT, KID. THAT WAS ONE IN A MILLION”]; A122 [LEIA AND CHEWIE HUG]; AA58 [CHEWIE IN COCKPIT]; A–Z120 [DOGFIGHT SCENES]; INT. X-WING AND Y-WING COCKPIT (WITH BLUE BACKING), SCS: 140, 143, 152, ETC. [CHATTER DURING DEATH STAR ATTACK]

STAGE 2: INT. SANDCRAWLER, SC 25 [C-3PO SENSES SANDCRAWLER STOPPED]; INT. DISUSED HALLWAY, B105 [LEIA AND HAN ARGUE AFTER ESCAPE FROM GARBAGE MASHER]; INT. DEATH STAR HALLWAY, SC: G163 [VADER: “WE’ll HAVE TO DESTROY THEM SHIP TO SHIP”]

STAGE 4: INT. GARBAGE ROOM, SCS: A97 PART [SOLO: “WHAT AN INCREDIBLE SMELL YOU’ve DISCOVERED”]; A100 [WALLS CONTRACT]; A102 & A104 COMP [LUKE’s SIDE OF DIALOGUE WITH C-3PO]

As first and second units scrambled to complete the film, which had fallen more than fourteen days behind, the situation wasn’t helped by a nagging sense that special effects work had stalled in the United States. “That part was the biggest problem that we encountered. Our biggest frustration,” Kurtz says. “Because we were shooting and shooting and getting closer and closer to the end—but we knew that nothing was being accomplished in Los Angeles.”

But at ILM, the feeling was mutual. “George is in England, you know, and I don’t care how articulate he is at describing what he wants, or how articulate I am at understanding what he wants, the truth of the matter is without him being here to see the film, it’s really tough to get that cohesive spirit of working together,” Dykstra says.

The reality was that during the entire length of principal photography, ILM completed only two shots, in which the escape pod disengages from the Rebel ship and sails toward Tatooine with the robots inside. “George had gone to England and John was busy, so Richard Edlund designed this whole shot, and Jamie Shourt and I stuck it all together,” Grant McCune says of the first shot. “We took the escape pod and tied the entire box that held the tube and took it up to the roof of the building. Then we took a great big volleyball net, with four guys holding it. I had a trigger to push the electronic pulse through the whole system. Richard took the high-speed camera that was mounted on top of the box, and we said, ‘We’ll try it and hope that the pod doesn’t break when it hits the net.’ We dropped it twice that day. When we got the film back the next day, the first shot was perfect—just exactly what they wanted. For three or four months that was the only shot that the shop was able to put out, so everybody was real happy about it.”

On Stage 2 Daniels worked with children as Jawas inside the sandcrawler interior.

The second was shot by Dennis Muren about a month later during the latter part of principal photography (with Doug Smith and Edlund, who took a look before his departure to London). “Richard was gone to England for four days, with John and Robbie,” Muren says, “so when they needed to do this shot of the pod dropping, they already had the background painting, so I composed the shot and gave some motion to the background through the stars and shot the pod using the big camera. I think it was Grant that came up with the idea, or maybe John, to have the pod mounted off-axis, so it would look like it was tumbling. When it goes down a distance, I had it sweeping in toward the planet all of a sudden, like the planet’s gravity is taking over. We didn’t want it to go in front of the planet, though, because we hadn’t worked out all of the bluescreen problems. I lit the shadows of the pod with orange light, as if it were being reflected off Tatooine. That was about it; it was very smooth. I shot it in one afternoon.”

Meanwhile, Ben Burtt, when not working at ILM, was diligently collecting sounds. “Seventy percent of the time I was recording,” he says. “About every two weeks I’d send a tape representative of what I’d recorded to England. I probably sent about twenty tapes during their shooting. I’d have my voice on the tape, saying, ‘Here’s ten examples of explosions; here’s some examples of jet planes; here’s a whole bunch of bear sounds.’ I even tried to make them do some phrases. I said, ‘Here’s a Wookiee getting angry, here’s a Wookiee being lovable.’ I never got any response, but they told me they did hear it. I honestly think they were so busy they probably never had a chance to listen to the tapes. I think Bunny Alsup heard them, you know, but I don’t think George had time. But that was the only way they knew I was doing anything. The other 30 percent of the time I was doing odds and ends at ILM.”

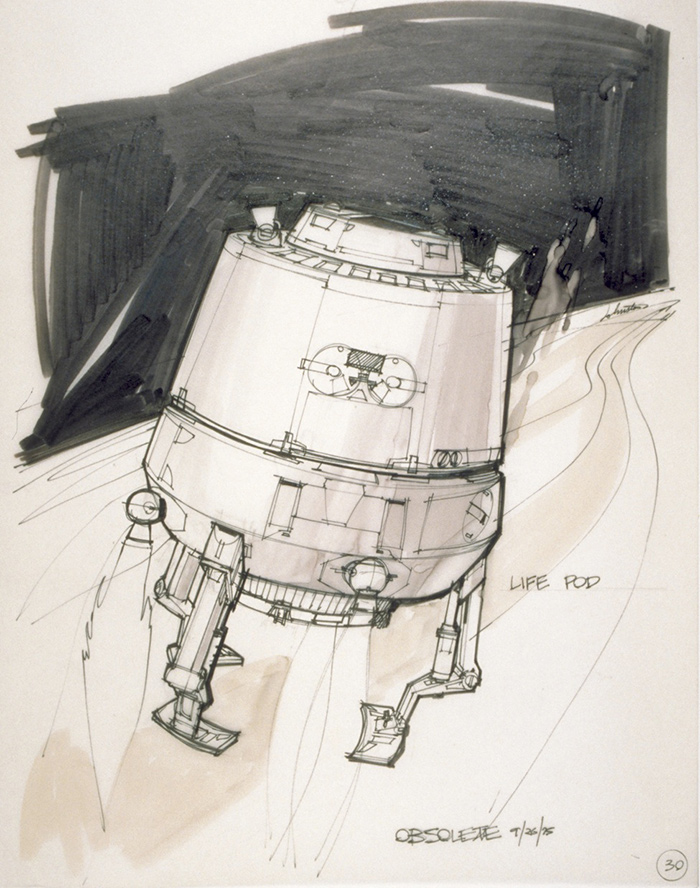

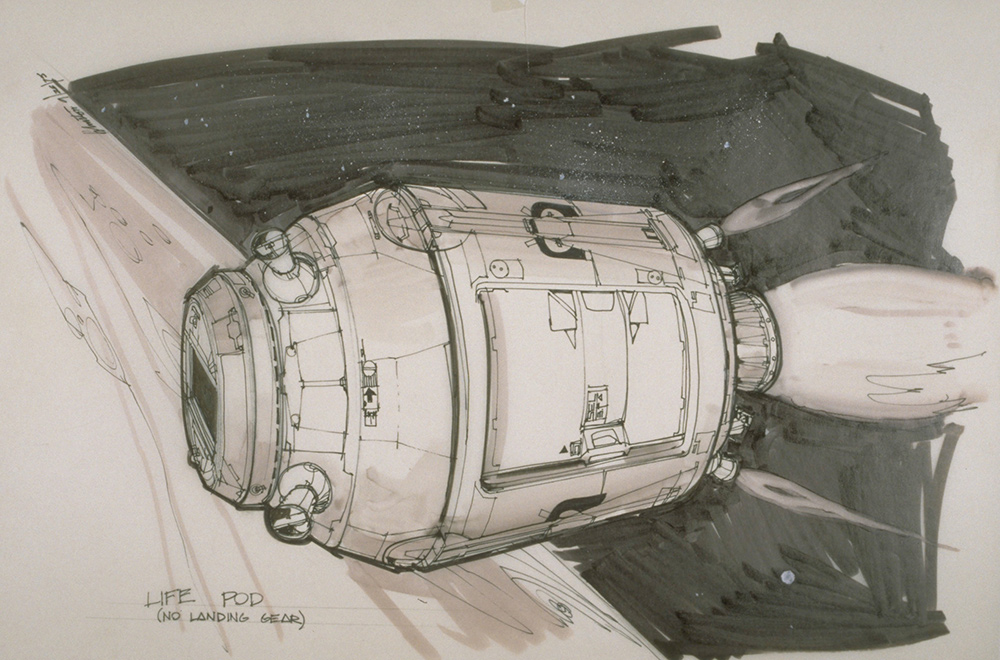

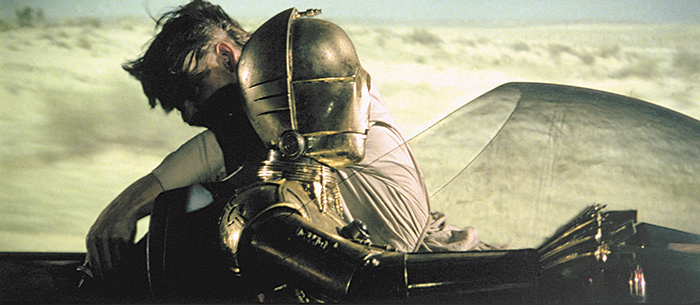

Joe Johnston did concept sketches of the escape pod being jettisoned, dated May 11, 1976.

Dennis Muren shot the pod as it descends toward Tatooine.

Joe Johnston also did concept sketches of the escape pod landing. While it was decided later that the pod didn’t need to be filmed actually landing, Grant McCune describes how they shot the pod being jettisoned: “We took electric solenoids and put three of them inside the tube that held the pod. The pod had a ring around it where these claws would hold on to it, which were connected to the solenoid, so that when you tripped the button, all three claws would pull out and drop. Down lower in the tube we put three-inch aluminum tubing in it with a number 44 flashbulb that lasts for 1.7 seconds; at the end of the tubes were the flashbulbs. Closer to where the pod was, we’d cut little square tables out and laid fish scales and mica dust on it, and we’d put air jets in with an air solenoid—so the final effect when it fired was the pod dropped through the tube, the explosive bolts would go off and then all the junk that was sitting around it that got exploded would float around in space right behind it [middle].”

A lifepod concept by Johnston, with “no landing gear.”

Burtt was right about Lucas, who by this time was suffering not only mentally but physically from the strains of making his movie. When John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, and Robbie Blalack arrived in England, via TWA Flight 760 on June 23, to oversee the switch to bluescreen, Lucas was hoarse and ill. “George is flying by the seat of his pants at all times— I mean, it is an enormous project,” Barry says. Stories of Lucas’s plight spread through his circle of friends, making their way to Spielberg on the set of Close Encounters where Bob Shepherd remarked, “George was getting wasted badly; I’m surprised he’s still alive.”

Despite his worsening condition, Lucas met with the ILM trio, and together they strategized as to how to best utilize the bluescreen technique. “The biggest change during filming was from front projection to bluescreen,” Lucas says. “We had shot the approach to the Death Star, but once we got the results, we realized it wasn’t going to work.”

“So we decided we were going to do a bluescreen,” Dykstra says, “and then we really got rolling again. We went over to England to check it out. At that point I think George felt like I knew as much as Tommy Howard [special photographic effects supervisor on 2001 and many other films], that there was some validity as to what I was saying—not that I was always right, but that I knew enough so maybe I could help.”

“We were faced now with remaking all of those shots at a later period of time,” Blalack says, “so the energy level went sky-high and we flew over there, helped them, worked with them to set up the shooting. We converted the VistaVision camera to take Nikon lenses, so it was compatible with what we were shooting; we did testing; and I went over to Kodak to see that we got the correct and best perforations on all the stock that they gave us. We did all of this coordination, running around, and spent about a week there, got over jet lag about three days into it, and flew back.

“But it was very exciting, actually seeing the full-sized pirate ship, seeing all of these people walking around and the stormtrooper extras resting in the sun, with half of their stormtrooper suit on,” Blalack adds. “We had fun in the midst of it, but we also realized what we were faced with. All the plates that we had sent to England, except one or two of the TIE ships going toward the Death Star, we never used again; that was all shelved, and we started over.”

“John Dykstra came to London when we started the bluescreen,” Kurtz says. “We wanted to make sure that we weren’t going to go back to the US and hear, None of this stuff is any good and you didn’t do it right. So he and Richard and Robbie all came to London, and we stood on the stage with Stan Taylor from Technicolor and went over everything very carefully. Then we sat down with John and went over the optical effects. We said, ‘We have 360 shots, that makes one shot a day projected out—are we going to finish on time or not?’ And John sat there and said, ‘If things go right, yeah, we can do that.’ We gave them the last chance at that time.”

News of the technical change didn’t go over well at Fox, where Ray Gosnell was monitoring costs back in the States. “Fox is very thorough,” Robert Watts says. “Particularly Ray Gosnell, the head of production—he knows his business. And it’s good for us because if we feel we’re being looked at carefully, it keeps us on our mettle.”

“The bluescreen cost another $100,000,” Lucas says, “but there wasn’t anything we could do about it, so there wasn’t any issue about it. We had to stay on schedule and we had to get the stuff shot. But lighting the bluescreen really slowed us down—it would take forever, hours and hours.”

While bluescreen tactics were decided upon, Lucas steered the first unit into the garbage masher set on Stage 4, where the actors got to slog around in increasingly nasty water on June 21 and 22. In addition to the walls that were rigged to contract, the special effects and makeup department had combined to create the Dia Noga. For everyone, however, the creature was less than it could have been. For Lucas, who had already tried a trash compactor escape scene in THX 1138, it was a case of another compromise, for what had started out in his drafts as a semi-transparent, fairly enormous monster with almost magical powers had been repeatedly scaled down by necessity and unworkable concepts.

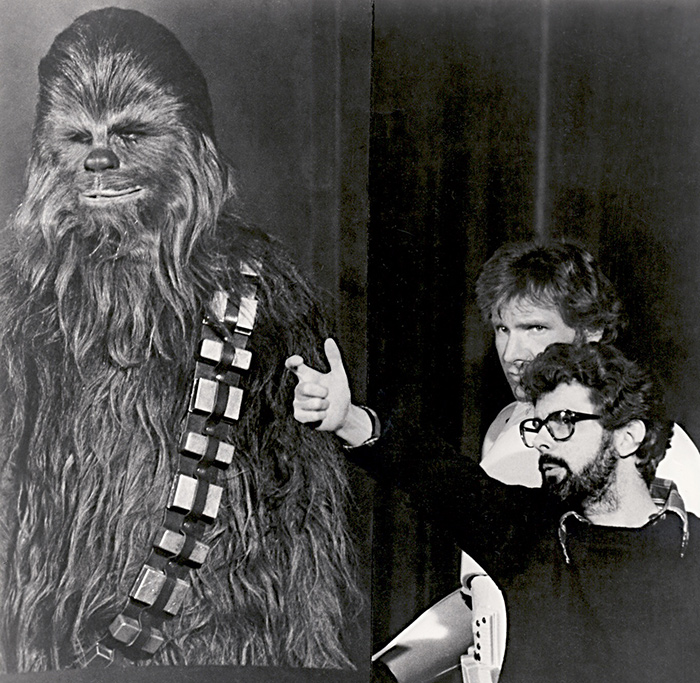

Lucas directs Mayhew.

The cameras roll in the garbage room.

The next scene was filmed in the “disused hallway”.

“It’s a cross between a jellyfish and an octopus, a transparent muck-monster,” Lucas says, “which can take any shape. It presses itself against the floor or in the nooks and crannies of the trash masher, or even in the trash itself, to survive. I had that same scene in THX and it failed miserably, so I had to cut it out.”

“The Dia Noga is a bit of a sad story,” Stears says. “I made the mock-up of the monster for George to see. He thought about it and came back, and we redesigned it. There was an awful lot of work that went into that monster, and it really is superb. Unfortunately, we can’t use it in its entirety. You’ll never see the body, just the tentacles.” During early preproduction, in fact, the plan had been to use diodes to inflate the monster, so it would seem to emerge from the water—but that idea went by the wayside when budget cuts forced Lucas to combine scenes. “We needed a smaller tank because we combined the two sets: the garbage room and the Dia Noga cave,” Stears explains. “Now it’s not physically possible on the set we have.”

“They started constructing the Dia Noga out of this very heavy plastic, and it started to get very cumbersome and big,” Lucas says. “It had to be run by ram jets, which I didn’t like, so I rejected that idea and I kept rejecting things to the point where all we had left was a tentacle.”

To protect themselves from the slimy water in which the tentacle lay, the actors had the option of wearing a wet suit under their clothes. Fisher, however, thought it was mandatory and soldiered through the two days. “I liked jumping through the garbage chute, but I didn’t like wearing the wet suit,” she says. “It was under my white gown, for protection—or I was going to look like Walter Brennan [a leathery and wizened actor] from the waist down from being in the water so long.”

Later on the same set, the ad-libbing of Ford and Hamill became comically contentious. “Then, of course, there is that famous fight between me and Harrison,” Hamill says. “In the scene where we’re trying to get out of the garbage masher, I was supposed to say, ‘Threepio, open the…,’ and give this long serial number. So I had planned all along to say, ’2–––,’ so my [own] number would be forever preserved on film. But the way the scene was blocked the day of, I wasn’t near the door—so Harrison got to say the line and he started doing his number and that really burned me up. I said to him, ‘Come on, say mine, I thought of it!’ But he kept doing his own and I got madder. Finally, Harrison read my number and said, ‘Happy now, you big baby?’ And I laughed because I felt busted ’cause I’d been acting like a two-year-old.”

Filmed in continuity, the next scene was shot in what they called the “disused hallway” (which would explain why it wasn’t crawling with stormtroopers who would’ve noticed four wet Rebels emerging from a garbage masher). “It was 105 degrees outside,” Fisher says, “so I wasn’t standing up straight and I was acting crazy. I was walking too fast because I wanted out of that hallway. But George said, ‘Now, act more like a princess. Stand up straight.’ Very black-and-white direction. Not anything weird and bizarre like other directors would say. It was very specific. ‘Faster’ you can do. ‘More intense’ you can do. And he did that in the disused hallway when it was so hot and he was the only one who seemed to know what was going on. He’d also refer to other scenes: ‘Remember how you were in the scene with Peter Cushing? Now just do the same in this scene.’ So it was never scary. I totally trusted him.”

Lucas has a rare smile as he looks at a collection of photographs taken during principal photography and assembled by Lippincott and Stanley Bielecki of SB (International) Photographic. “There was one point during filming when George and I figured we were making about $1.10 an hour, with all the time and work we were putting into it,” Kurtz says.

Peter Mayhew, upon completing his role as Chewbacca, returned to his day job as a hospital “porter” or orderly.

Thursday, June 24, was Harrison Ford’s last day. “I get a concept of the character,” Ford says, “but I don’t get a concept of the way the character will behave until I see how the other people are going to act in a scene and until I get to see what the set is like and the situation. If you can develop a kind of confidence in the people you’re working with …” In the interview, he trails off, but the conclusion is fairly clear: Han Solo was a result not just of Ford’s own interpretation of the character and Lucas’s direction—Solo was also the right response to the performances of his fellow actors.

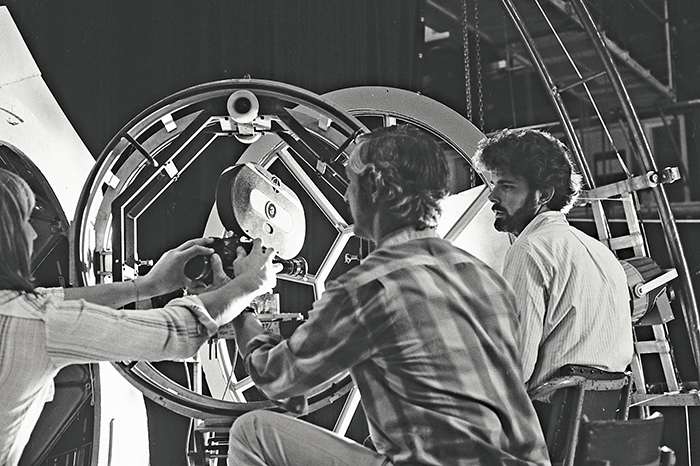

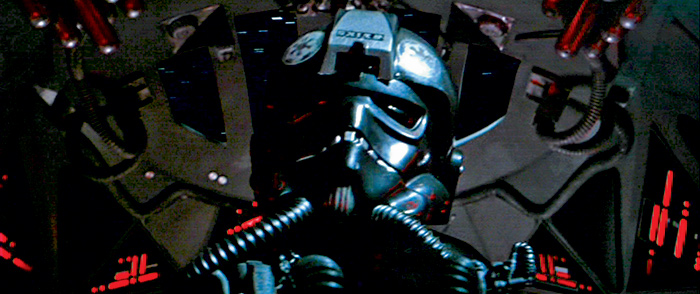

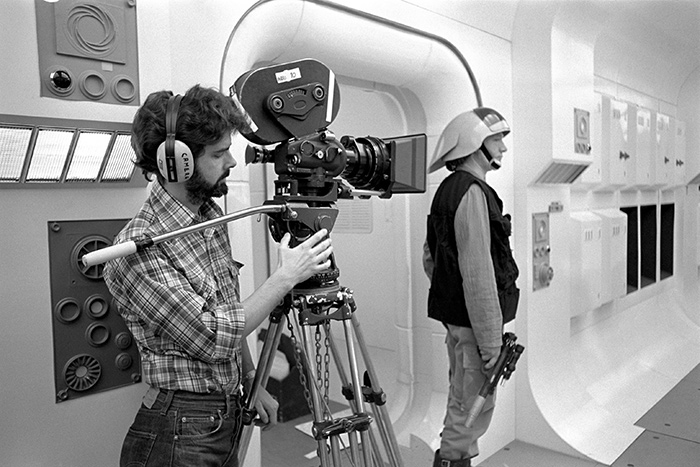

On Stage 8 more cockpit scenes were quickly shot, with Lucas taking a look at Vader in his TIE fighter.

On Stage 4 Hamill and Ford finish their gunport scenes.

The Panaflex camera used for filming Biggs (Garrick Hagon) had a list on it of the other films in which it’d seen action.

On Monday, June 28, Ford flew to Los Angeles, along with Fisher, who was taking a break. And it was another last day, this time for Peter Mayhew. The Princess and the Wookiee had enjoyed some good times together. “We’d go to lunch at the Chinese restaurant, and I’d have my ‘hairy earphones’ on, and Pete Mayhew is seven foot two,” Fisher says, “but they’d serve us like we were regular people. That was my favorite part. I’d go out to get cigarettes and magazines in my entire outfit, and … nothing. They would just give them to me.”

That Monday also saw Dykstra, Edlund, and Blalack return to ILM. Indeed, for the first time the progress reports mention “blue backing,” in shots of X-wing cockpits, as production entered a new phase.

SCS COMP: 173; SCREEN TIME: 103M 08S.

REPORT NOS. 71–84: FRIDAY, JUNE 29–JULY 16, 1976

STAGE 8: INT. COCKPITS, SCS: 170 [BIGGS IN TROUBLE]; I220, 148 [WEDGE: “LOOK AT THE SIZE OF THAT THING”]; N220, ETC. [ATTACK ON DEATH STAR]; 240 [BEN TALKS TO LUKE, WHO SWITCHES OFF HIS TARGETING COMPUTER]; LUKE’s SPEEDER ON EXT. DESERT WASTELAND (FP), SC: 34 [LUKE SPOTS FUGITIVE R2-D2]

STAGE 2: GUN EMPLACEMENTS, SCS: 158, Q163, ETC.

STAGE 4: INT. GUNPORT, SCS: 232, A120–A123 (CLOSE-UPS OF MARK HAMILL)

STAGE 9: INT. REBEL STARFIGHTER, SCS: 11 [LEIA: “LORD VADER … ONLY YOU COULD BE SO BOLD”]; 6 [THE DARK LORD BREAKS THE REBEL’s NECK]; A6 PT [C-3PO: “DON’t CALL ME A MINDLESS PHILOSOPHER …”]; 4 PT [C-3PO: “WE’ll BE SENT TO THE SPICE MINES OF KESSEL …”]; C6 [STORMTROOPERS STUN LEIA]; 2 PT [C-3PO: “DID YOU HEAR THAT? THEY’ve SHUT DOWN THE MAIN REACTOR”]; A3 [“THE AWESOME, SEVEN-FOOT-TALL DARK LORD OF THE SITH MAKES HIS WAY INTO THE BLINDING LIGHT OF THE MAIN PASSAGEWAY”]

One last attempt was made to do front projection with Hamill and Daniels in the landspeeder, also on Stage 8.

With cast and crew fifteen days behind schedule, Fox insisted that the Star Wars production split up into several units and shoot as many things as possible at the same time. The progress reports from the last two weeks are thus filled with statistics relating to multiple crews working on different stages and sets as they shot inserts, pickups, close-ups, and miscellaneous coverage as rapidly as possible, while Lucas continued with the first unit. The director tried to explain to Fox that it would cost much less to simply extend the schedule, but executives were adamant that the film had to finish no later than mid-July.

“Alan Ladd just couldn’t go to the board and say the film wasn’t finished on a given day,” Lucas says. “It had to be finished.”

One by-product of the intense need to wrap things up was that even though front projection had manifestly failed, a last attempt was made for a few shots of the landspeeder traversing the desert. With Hamill and Daniels in the physical vehicle, they were filmed against front-projected plates in an effort to save time that would have to be otherwise tacked on to the US pickups. Meanwhile, the second unit traveled with the actors for a shot outside the Cardington Air Establishments in Bedfordshire, a stand-in for the exterior of the secret Rebel hangar on Yavin.

Work was complicated by the fact that during his performance in the grips of the Dia Noga tentacle, Hamill had burst a blood vessel in his eye, making it impossible for him to shoot his X-wing cockpit close-ups until the very last days, and forcing scenes to be rescheduled. Other mishaps were recorded, including an increasingly ill Gil Taylor, and a larger and larger number of electricians who had to be called in for the intricate bluescreen lighting. The conflict between DP and producer came to a head when the former discovered the latter rearranging the lights. In some stills taken from this period, Ronnie Taylor is the acting director of photography.

Carrie Fisher returned to this melee on Sunday, July 4, bearing a gift for the beleaguered Lucas. “Carrie brought him a Buck Rogers helium pistol,” Hamill says. “And George wouldn’t put the thing down. We saw him in the hallways up at EMI, just kinda twirling it around. Couldn’t pry it out of him.”

Fortunately Lucas was able to compartmentalize, reserving space for amusement while also driving his troops on—but still only to 5:30 PM. It didn’t help that Lucas would speak to his friends Steven Spielberg and Marty Scorsese, who were making their respective films with 120-day shoots of twelve- to fourteen-hour days—more than twice the time that Lucas had.

“Magazines were calling and asking, ‘Is George unhappy?’, and I said, ‘Well yes, George is unhappy,’ ” Barry recalls. “And they asked why was that, and I answered, ‘Because making movies is very difficult. Movies are not done in a jolly atmosphere of self-congratulatory lunches at the Polo Lounge.’

“The potential problem on a picture like this is it can become a committee movie,” Barry adds. “There are so many people involved and so many forces working on you, working on George, that the amount of choice you’ve got is limited all the time by these outside pressures.”

Lucas nevertheless had the wherewithal to make a last crucial decision. Walking through the sets one night with John Barry, they toured the Rebel ship, which was really the redecorated main hold of the Millennium Falcon—and Lucas found it wanting. “Sometimes we tried to re-dress a set and use it again,” he says. “But I looked at it about a week or so before shooting, and I said, ‘I can’t possibly shoot the sequence on this set.’ The original set was the little alleyway with the Princess and the robots. That was all we had. And I just realized I couldn’t shoot a battle, five pages of dialogue, and all these people running around, and have it all take place in one little hallway.

Printed dailies from the end of principal photography, July 1976. Lucas directs the

extras as cameras roll for the scene in which stormtroopers blast their way onto the

rebel ship.

(1:12)

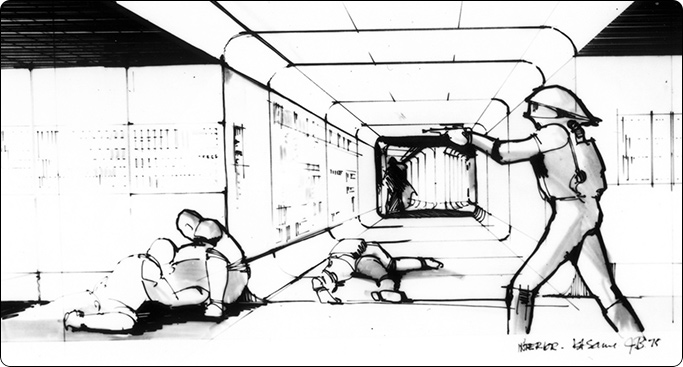

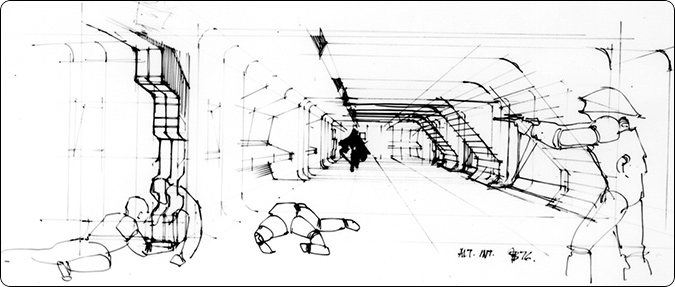

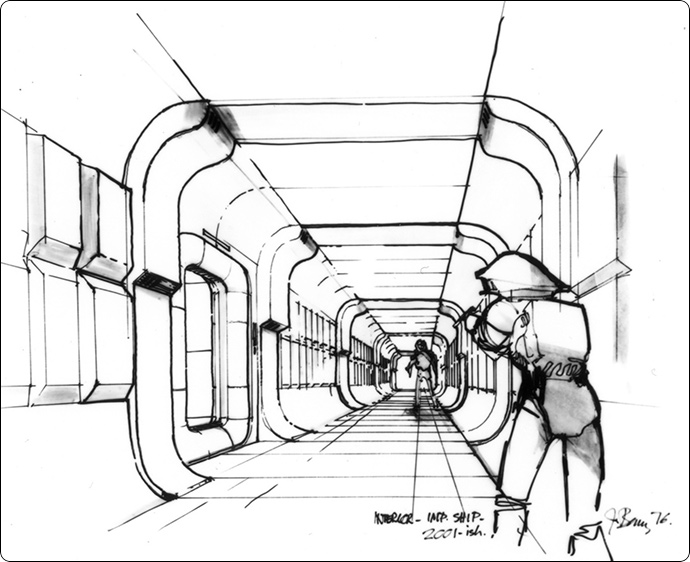

John Barry originally sketched ideas for the Rebel ship shootout with a much longer and wider corridor that corresponded to the first pirate ship layout.

His 1975 drawing also shows a different setup from his 1976 sketch, which is closer to what was filmed on July 9.

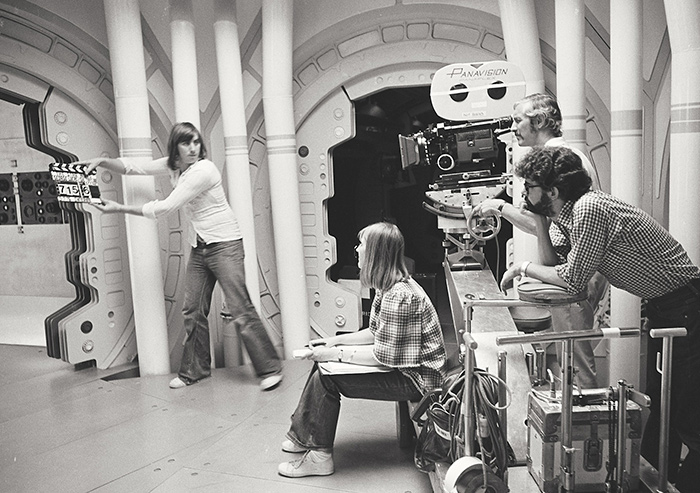

Filming on July 9, with Ann Skinner, sitting.

“So I said, ‘John, you have to build another big hallway next to this little hallway’—and that created a whole big ruckus with Fox and everybody, because it cost a lot more money. I got a lot of flak—everybody came down on me. There was a lot of screaming and yelling. But ultimately, as the director, if you decide that it is vital to the film, it is vital to the film. We had to have it; I couldn’t make the movie with half a set. I had really tried to cut corners wherever I could, but once in a while we’d reach a point where we needed to spend the extra money. So John built a new white set. I was very concerned that the opening, the first interior of the film, be spectacular and look opulent, and not just be a set re-dress. We had a lot of problems with that but eventually John, who is a genius, did it.”

“One set we changed quite a bit was the interior of the opening spaceship,” Barry says. “We added a great white hallway to it, because it had been a revamp of the interior of the Millennium Falcon. Also, I think George wanted the set to look, at first sight, like you are in your conventional all-white interior 2001-type spaceship—and then the door blows down and in comes Darth Vader—black against a white hallway!”

The explosives ignited during that opening shootout caused at least one stuntman to go to the hospital. “John Stears got a little ambitious and blew the walls off the set a couple of times,” Kurtz says. “But any powder man does that occasionally. Misjudges a little bit. But he did a really good job on the gunfights in the white hallway. He was much faster than any other powder man that I’ve ever worked with.”

“When the laser blasts hit a wall, I didn’t want it to be just a little squib like you normally have on a gunshot,” Lucas says. “I wanted it to be a big, huge flash every time it hit. So we tested out large squibs so we could make big explosions.”

The last few scenes of principal photography were shot on Stage 9. In scene 6, the rebel officer getting his neck broken was played by Peter Geddis, according to the cast list.

In scene 11, the “commander” is played by Constantin De Goguel (sometimes billed as Constantine Gregory).

Originally the Rebel ship set consisted of only the redressed Falcon hold (with Fisher).

Printed dailies from July 8, 1976. Prowse as Vader chokes the rebel captain.

(0:50)

“I remember that I had to shoot a gun and that I got felled by a paralyzing ray, which I loved,” Fisher says, “because I knew I would have to do what my mother called ‘pratfalls.’ ”

Amid the chaos of the sparks and multiple units, everything went right those last few days: The actors gave great performances; the lighting, sets, and dressing were beautifully done; and production finished on time. The progress report for July 16 reads, “Completion of principal photography in U.K. today. Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher completed their roles today and will travel to Los Angeles tomorrow, Saturday, July 17, 1976. George Lucas will travel to USA on July 17. Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker also completed their roles today. The editing equipment and film will arrive in the U.S. on July 27. Scenes remaining to be shot (in USA) are now as follows …”

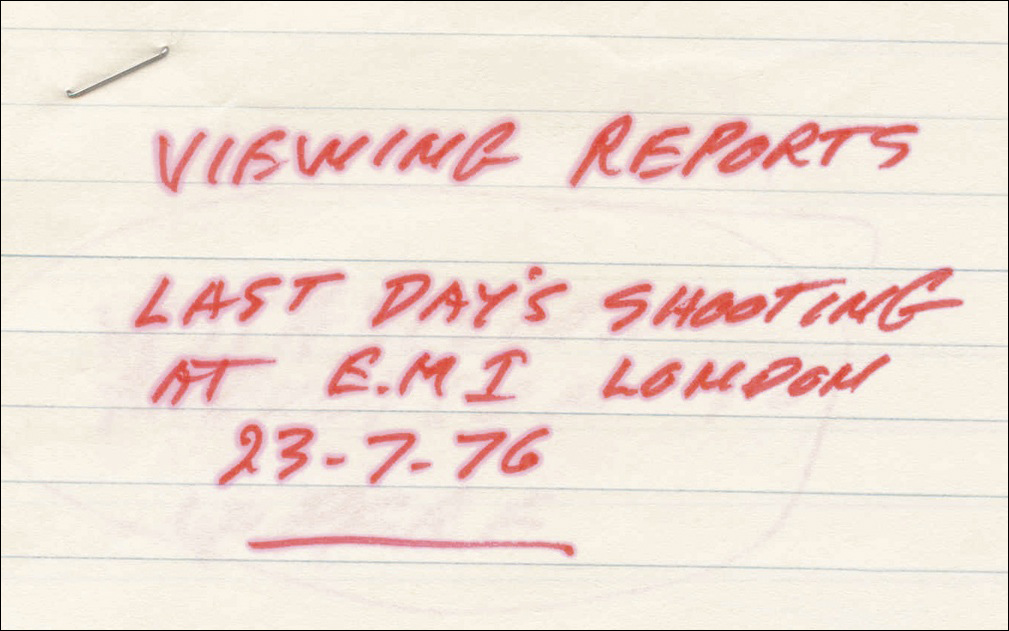

A list of those incomplete scenes follows, mostly with R2-D2, the banthas, the landspeeder, and the sandcrawler—pretty much all shots that had been handicapped for technical reasons. There would also be one more day of shooting in the United Kingdom. The first official day of postproduction was the following Friday, when an insert shot of Luke’s gloved hand turning off the targeting computer and of C-3PO in the Rebel ship corridor were needed, so stand-ins were used. Derek Ball, the sound man, also traveled to the home of Shelagh Fraser (Aunt Beru) to record “wild track”—lines that can be inserted anywhere when the actor is off camera. On July 23, second-unit cameraman Brian West used his Arriflex to capture: R2-D2 for scene 2; various hands on various controls, in assorted cockpit shots; and, once again, the landspeeder with a Luke double against bluescreen.

“I kept checking and asking, ‘Do you realize I’m working on that day,’ ” Daniels says. “And they said, ‘Yes, you’ll be finished.’ And of course I wasn’t so they asked my stand-in to do it. She was a beautiful blond debutante, a girl small enough to get into my costume. She was really quite good.”

By the end of the 84-day shoot, which finished twenty days over schedule, production had exposed 322,704 feet of film, with 226,717 feet printed, and recorded 219 magnetic rolls for sound. They had shot an average of one minute and thirty seconds of script a day. Hamill led the field of actors, with 70 days worked, next to Daniels’s 54, Ford’s 42, and Fisher’s 37—all performed on about 100 sets. “But what we did was group the sets all together into composites, so there were only about 40,” John Barry says.

Principal photography cost more than planned, but not wildly so. “Gil Taylor’s lighting budget was the source of the biggest overage, along with transportation,” Kurtz says. “He’d looked at the sets, all the plans, and worked out with his gaffer that the average was supposed to be 10 electricians a day.” But they ended up with 20, some days 40 electricians on the big sets, most of whom were called in for the shift to bluescreen. “That automatically kicked it up, because we had to dig out about 50 extra arc lights,” Kurtz explains. “The days that we were going blue backing, we had 60 electricians working on the set. Every 20 minutes those guys had to change the carbons on about 70 white-flamed carbon arcs. So that was a huge overage right there. That wasn’t Taylor’s fault.” Nor were the Death Star hallways and hangar, which John Barry had to repaint about seven shades of gray lighter, so they wouldn’t require so much illumination.

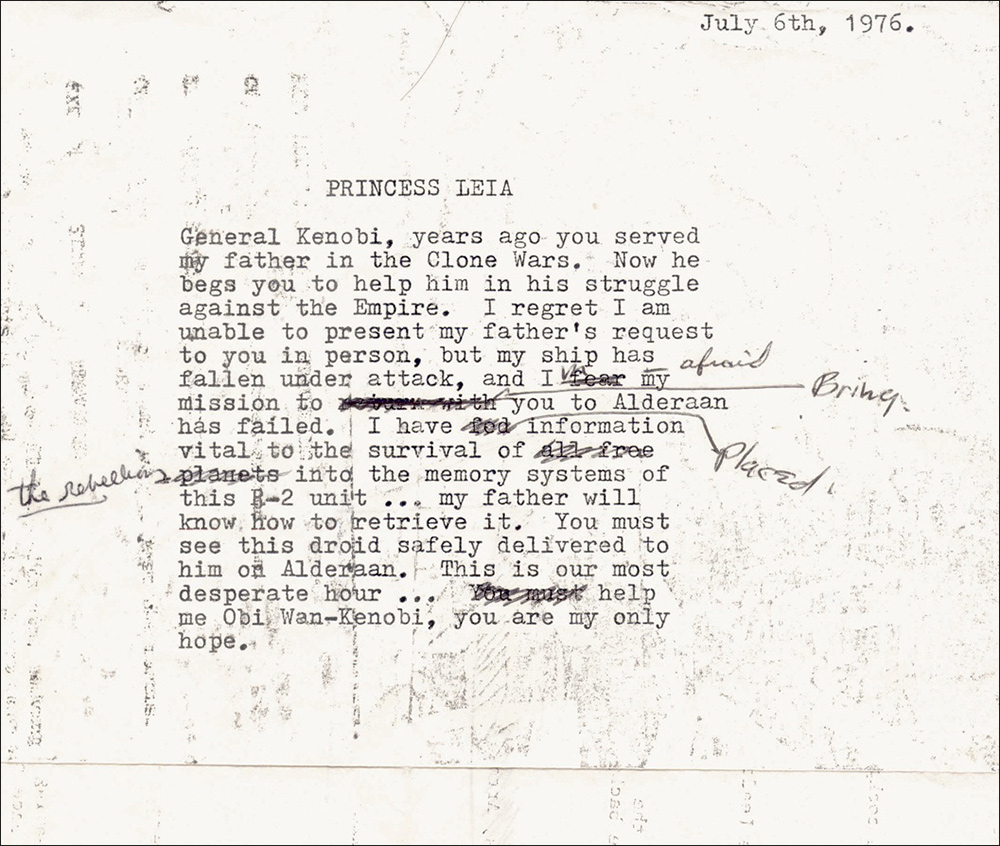

One scrap of paper dated July 6, 1976, contains Lucas’s changes to Princess Leia’s hologram monologue, which was shot on July 16, while another indicates the last day of second-unit shooting on July 23, 1976.

Gil Taylor would eventually express regret about the way things turned out. “I only wish I could have my time over again to have a slightly different relationship with George,” he says.

“Most of the rest were just nickel-and-dime overages,” Kurtz adds. “Set construction overages, rescheduling … The rest was more or less okay.” Circumstances aided the bottom line, when the British pound was devalued that year, creating a windfall of about $450,000, which decreased the total overage in the UK to approximately $600,000.

The final appreciation of the experience in England was mixed, but edged toward the positive. “Some of the people were enthusiastic about the picture and some of the people were indifferent,” the producer says. “I think 60 to 70 percent worked out well. We were working with people we had never worked with before, so I don’t consider that a particularly bad record.”

Lucas agreed: Some worked out, some didn’t. “Part of the problem is that you’re asking the impossible of people,” the director says. “And they can either do it or they can’t. But you can’t blame or fault somebody for not being able to do the impossible—by definition, it’s impossible.”

SCS COMP: 344; SCREEN TIME: 124M 02S.