Ashattered Lucas made a couple of stops before returning to California: Mobile, Alabama, to visit Spielberg on his set; and New York City to say hello to Brian De Palma. Lucas had assembled booklets of black-and-white production stills, on-set photography of Star Wars, which he gave to his friends, including film critic Jay Cocks.

“When he wrapped at Elstree he came straight to my set in Mobile, where I was shooting Close Encounters, and he was so depressed,” Spielberg says. “He brought a whole bunch of stills—the sandcrawler and the Jawas—and I was just amazed, but George was so depressed. He didn’t like the lighting; he didn’t like what his cameraman, Gil Taylor, had done for him. He was really upset.”

Back in Los Angeles, Lucas attended a screening of Carrie with its editor Paul Hirsch and director De Palma. Lucas then returned to ILM on August 1, 1976, to face a situation even more dire than the one he’d left in England. The pressures awaiting him were such that, even decades later, they haunted him. At the 30th anniversary of ILM in 2005, during his short speech at their new San Francisco Presidio headquarters in the Letterman Digital Arts Center, Lucas recalled his experience: “When I got back, they’d spent half their budget, and had only one shot in the can. There were 45 people and about 360 shots left—and they thought they’d be able to finish the film easily in only eight months.

“On my way back from ILM,” Lucas says, “I started getting severe chest pains, since my life was collapsing around me. I had to recut the movie from scratch and ILM hadn’t created a single shot that was viable. I was really hurting, so when the plane touched down I went straight from the airport to the hospital.” They kept Lucas overnight. By morning, the doctors determined that he had not been having a heart attack, and Lucas was allowed to leave.

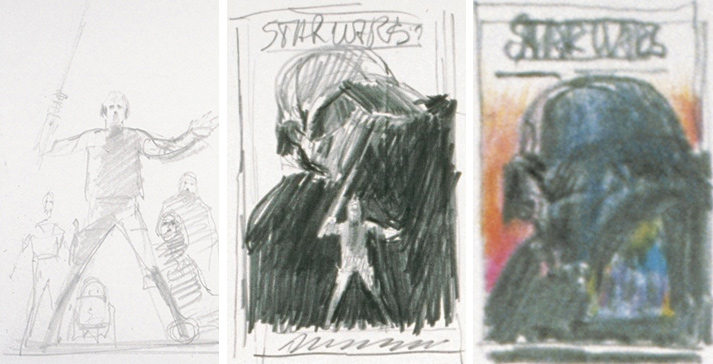

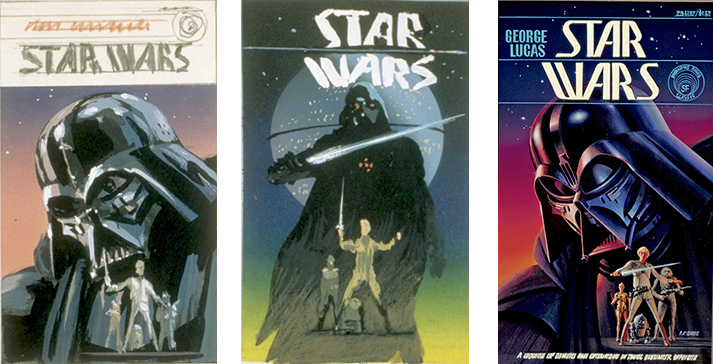

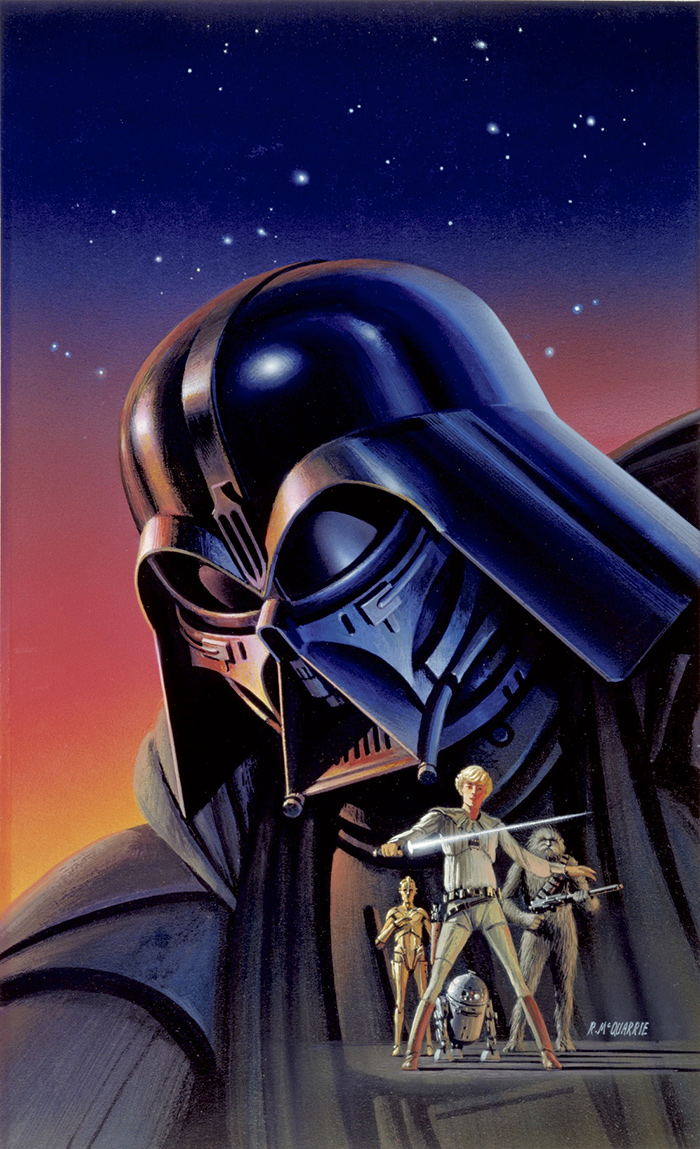

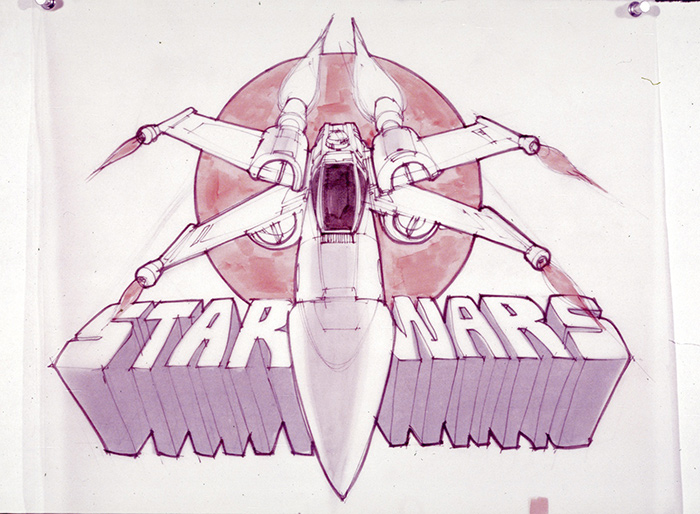

During most of May and June, Ralph McQuarrie had worked on other projects, but from July 19 through July 22, 1976, he worked on the “roughs for S.W. book cover.”

On August 11, 1976, he finished the illustration and started work on “I.L.M. Star Wars T-shirt art.” By this point, Lucas had dropped The from the title, at which point it became Star Wars.

Even if the ILMers were right, Star Wars would just barely make its release date in the spring of 1977. As Lucas mulled over the situation at Industrial Light & Magic, he came to certain conclusions. The first was that it was being run as a research facility rather than a film production unit. The equipment, though fabulous, had taken longer than predicted to build, tests were still being carried out, and the experimental explosions hadn’t looked good. Procedurally, they were completing a shot and then waiting until the next day to make sure the rushes were okay before moving on, despite the Dykstraflex. “George ended that as soon as we got back,” Kurtz says. “No holding any shots. You finish the shot, you break the set up. If you have to do it over, you reset. We can’t worry about the rushes. That was a part of the delay. They were experimenting and they were working under a different set of rules.”

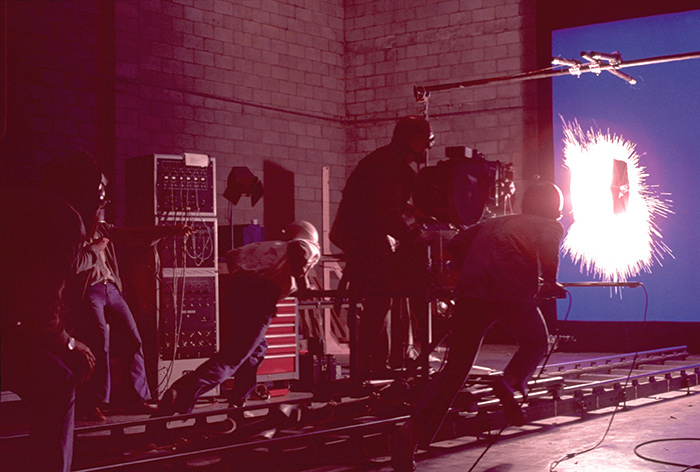

“We didn’t even know how to do a bluescreen shot at the beginning of Star Wars,” Richard Edlund notes. “So I brought in Bill Reinhold, an old-timer who had done It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World [1963], to teach Robbie Blalack how to do bluescreen.”

While Lucas and Kurtz came to grips with one problem, an equally important task was beginning up north in San Anselmo, within Park Way’s converted carriage house: the editing of the film. ILM’s initial goal—the one that had been abandoned during principal photography—was to finish the escape from the Death Star scenes. But now that ILM was going to be adding special effects to the bluescreen elements already shot in England—the reverse of what had originally been planned—a work print of that sequence had to be created before they could start. The first and primary task of postproduction was thus to cut together that sequence so ILM would know how long each shot was, where the camera would be, and so on. Fortunately, this was the moment Lucas had been working toward for more than three years—to have the raw material that he could meld into a cinematic experience.

“I really enjoy editing the most,” he says. “It’s the part I have the most control over, it’s the part I can deal with easiest. I can sit in my editing room and figure it out. I can solve problems that can’t get solved any other way. It always comes down to that in the end. It’s the part I rely on the most to save things, for better or worse. Everybody has their ace in the hole—mine’s editing.”

Harrison Ford, who had already experienced the before and after of American Graffiti, was well aware of what Lucas would do in editorial. “That’s one of George’s great virtues: putting a movie together to create an experience for the audience,” he says. “That’s where a touch here of this character and a touch there of that one will seal up your impression of what he is going for. It’s not fully resolved until it’s done by him.”

“I think of it in terms of cinematic style, which is why there is a lot of cross-cutting in my movies,” Lucas says. “Cinematically, it’s the way I like to tell a story. But no one had been editing on the movie for several months, so the first thing we had to do when we got back to San Anselmo was to reconstitute everything that had been cut in England, put it back in dailies form, and start from scratch. It turned out to be even more of a horrendous job than we thought it was going to be. We were running against a terrible time problem, so we hired an editor, Richard Chew. He and my wife, Marcia, who was also an editor, raced to get a first rough cut of the movie ready by Thanksgiving.”

Chew and Lucas had originally met through their mutual acquaintance, John Korty, and Chew of course had been Lucas’s first choice as editor the previous year. “I had gotten other offers because of the success of Cuckoo’s Nest,” Chew says, “but nothing had come along that I felt I wanted to live with for six months or a year—when the chance came again to work on this. I had already heard that George was coming back from England and that they were very unhappy with what the English editor had done with the film. George wanted the whole thing redone. He asked Marcia to work on the final battle sequence, so ILM could start, and he needed someone else to start at the beginning. And since I’m neighbors with him and he was familiar with my work …”

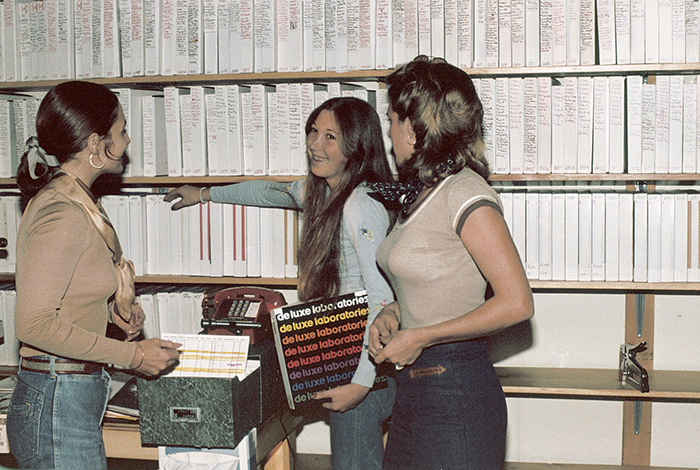

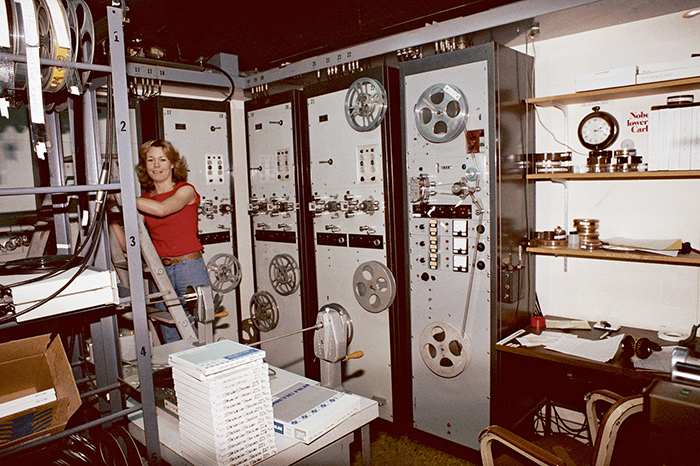

The overarching concern was to cut things as tightly as possible, with no unnecessary special effects footage, so neither money nor time would be wasted. But before anyone could begin, they had to create coding systems and standards that would enable the editors and ILM to work together. Coordinating that effort was Mary Lind, who ran the Film Control Office down in Van Nuys. She had actually started back in August 1975, recruited by Jim Nelson, who was an old friend of hers, after they’d met accidentally in a Schwab’s drugstore. She and her team were responsible for the whereabouts of every frame of film—a monumental task, particularly as postproduction wore on. Eventually, she wound up with 23 cross-referenced notebooks tracking each frame as it traversed often a dozen departments (top right). “I remember we had about 60,000 feet of live-action VistaVision out of England,” Lind says. “It was sent here and reduced from 8-perf to 4-perf so that Marcia and Richard could cut it.”

This initial mechanical work took about four weeks; another two weeks was spent coding the reduction prints to the VistaVision prints. “If you were going to pick up a code number to find negative and it was code number 400, it was actually code number 800 in VistaVision,” Lind says. “Oh God, it got crazy!” Another complication occurred when Film Control discovered that “the film put together in England was damaged,” Chew reports. “As though people hadn’t cared what they were doing—to the point of slamming it all together and saying, ‘Screw this job!’ So they were a bit upset at ILM because they had to go through the whole thing.”

While they were waiting up north for the processes to be completed down south, Chew started at the beginning, on the Rebel ship and the droids. “One great thing about working with the robots was there weren’t any lip-sync problems for an editor to worry about,” he says. “We just chose whatever looked good and then we could cheat in anything else. For See-Threepio we had at least the production guide track, where Anthony Daniels is speaking underneath the mask, but for Artoo, whenever we came to him, either George or I would say, ‘Phoove-orvr-ovrrrrrr!’ We’d do something that would sound appropriate as a reply. It was a good way for me to ease into the style of this film.”

As soon as the properly coded and reduced 35mm special effects footage was delivered from Film Control, while Marcia concentrated on the end battle, Chew turned to the escape from the Death Star. “I started working on the picture the beginning of August 1976,” Chew says. “George said he had to lock that sequence by September 15 for ILM to do all the optical work and the miniatures, but he was so busy, the only thing he could say to help me was, ‘Here’s the scene—don’t look at the English cut, because it could influence you and I want you to start from scratch.’ So I was stepping into the project cold. I had all this material, with bluescreen, and I had no idea what we were going to see out there. The only guide that George could give me was this black-and-white dupe of World War II dogfight news footage. So during the first three days, while keeping in mind what George wanted, I was already indicating with grease pencil the paths that the TIE fighters would take, where the explosion would come from, and when laser beams would fire out of the guns.

In the Film Control Office, film librarians Connie McCrum and Cindy Isman work with film control coordinator Mary Lind.

Peeking out of the drawer is an ILM shot tracker.

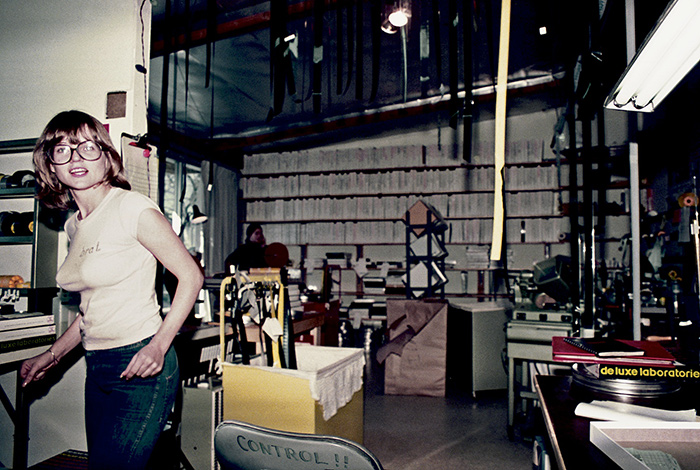

In the same room was ILM editorial.

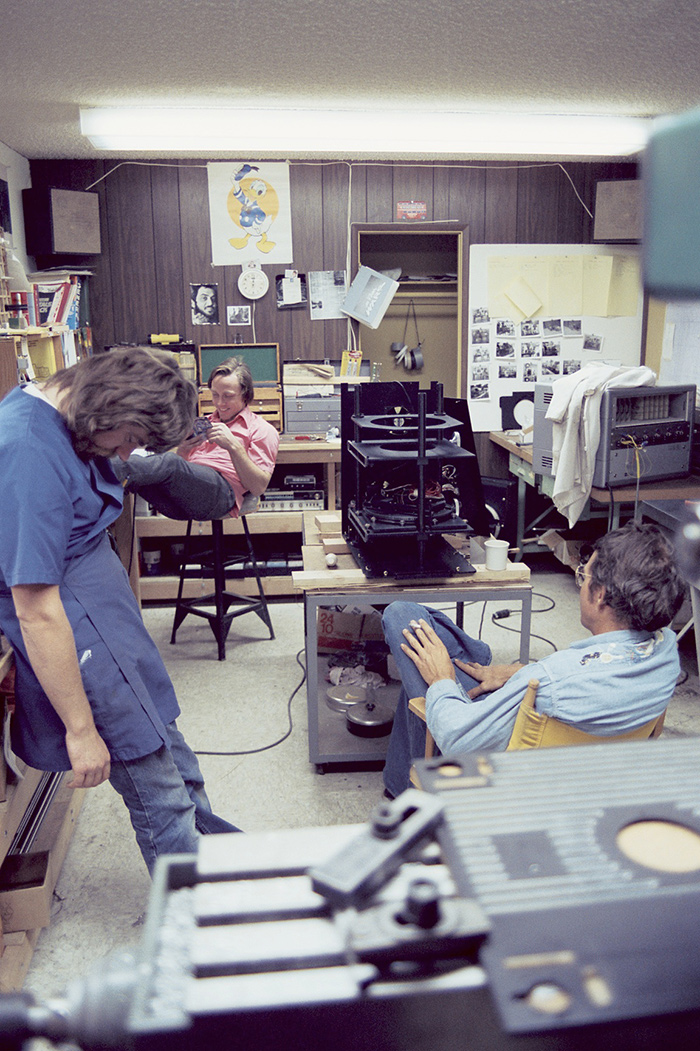

Every department was fairly cramped, including editorial, optical, the machine shop (with Dick Alexander, Doug Barnett, and Bill Shourt), and the back room.

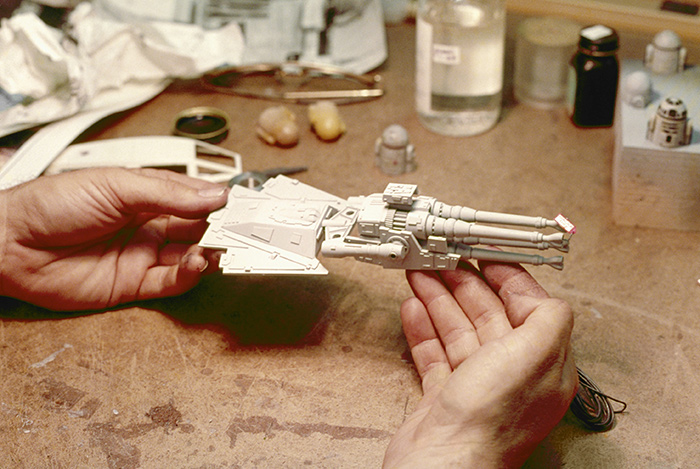

The back room was filled with models used for kit bashing. In fact, ILM spent about $1,700 on art supplies and $2,900 on model kits.

“We wanted to establish the spatial relationships,” Chew continues. “There were some very nice angles that George had shot; and when Han or Luke pivoted in their chairs, they cast these nice shadows on the wall behind them. We would choose stuff like that, not taking into account where the TIE fighters were. There were some lines like, ‘Here they come,’ or ‘Do you hear me, baby, hold together,’ but those were the ‘wild cards’ that we were able to shift around to bracket whatever action was occurring.”

After Chew was able to piece together a rough cut of the sequence, as it was a precedent-setting moment in postproduction, Lucas took over. “George is enough of a film craftsman, besides being the ‘general’ of this huge army, that he really wanted to get his hands dirty,” Chew says, “to cut frames off and manipulate things, because I think he is happiest when doing that. So he had me put together the gunport sequence so that he would have something to play with. Then he went upstairs to his editing room and Steenbeck editing table and looked through all the trims, while I continued working from the beginning of the film and Marcia was working on the end. He worked on it weekends up until the time that he locked it on schedule.”

“I cut one sequence myself,” Lucas says. “It was too hard to explain what I wanted, so I just cut the whole thing. It had to be cut right away because of the special effects. We had to know how to do it, so I sat down and cut it.”

“After the live-action editors had their time to work with the material in San Francisco, it hit our room—when it all had to be done at once,” Mary Lind recalls. “And of course they couldn’t give us little sections at a time, so when those escape from the Death Star rolls arrived, it was 18 hours a day just figuring out numbers. There were people sleeping here.”

Once the film had been logged, ILM began its first true sequence—with a year of investment in equipment and experimentation on the line.

“Kissinger always said that the essence of negotiating is having an ass that doesn’t get tired,” Tom Pollock says. “The one that sits there the longest, and says the same thing over and over and over again, is the one that survives.”

Perhaps spurred on by the return of Lucas, Twentieth Century-Fox finally agreed to the official wording of every single item, the result of years of hard deliberations between, representing their client, Andy Rigrod and Tom Pollock, and, representing the studio, Mort Smithlise, Donald Loze, Lyman S. Gronemeyer, William Immerman, and often two or three people from production.

“Studios are very traditional and precedent-oriented,” Rigrod says. “If you ask for something that they normally don’t give, no matter how small it is, they get very defensive about it. So I remember the negotiations as endless. We were in this huge paneled room at the studio—it looked like a meeting of the board of directors. There were sometimes as many as eight people sitting around this huge table. We would sit there for days and negotiate and argue. Every line of the agreement was read and changed. It went through four or five revisions. It was the most lengthy, complicated, and difficult contract negotiation I’ve ever seen.

“The thrust of it was that Lucas was very concerned that all versions of the picture would be controlled by him,” Rigrod adds, “with as little interference by the studio as possible. We were actually having a race to see whether the contract or principal photography would be done first.” The movie won by more than a month.

The seventy-four-page “long-form” contract was signed on August 27, 1976. The most important part of said document is Exhibit D, which begins with the phrase, “[The Star Wars Corporation] owns all Sequel Motion Picture rights in and to the picture.” The intricate legalese, which necessitated its own in-contract glossary, also stated that Lucas would maintain control over the licensing of his movie and the sequels, with profits from merchandise—which historically had meant T-shirts and movie posters—being split fifty-fifty for Star Wars.

The lone wolf of production, Ben Burtt also had to be taken care of when Lucas returned. “By the time they came back, I was pretty nervous as to what was going to happen,” Burtt says. “I’d had very little feedback and I was still under the impression that Walter Murch was going to step in and take over. I thought that maybe I was through with being employed. Gary would say things like, ‘Now a real sound effects editor is going to run the picture …’ I had no previous track record in this area, and they were not about to give the responsibility for a film of this magnitude to some completely inexperienced sound editor, which is what I was. Of course I was offended by that, because I’d spent a lot of time on the film. This was my first big job, and I wanted it to turn out good.

“Finally in August, they said they wanted me to go to San Anselmo for a week or two just to make up some effects for the temporary version of the picture,” he adds. “Basically I was going to transfer the sound library up there. I had it really well organized and cataloged so that anybody could go through it, so I kept thinking I was going to turn it over to somebody, and maybe that’s what they intended. I don’t know. But I went to San Anselmo and stayed for seven months instead of three weeks.”

In September, as the effects house was about to begin on the escape from the Death Star sequence, changes had to be made at ILM. With Bob Shepherd gone since March, Jim Nelson had been the production supervisor, working with John Dykstra—a combination that, according to the producer, didn’t work out well. Dykstra, as the leader of his troops, was perceived by different people in different ways. For Shepherd, Dykstra had been the totally committed leader, but Kurtz felt differently. “John wanted to be buddies with everybody,” he says. “He didn’t like yelling at people. From a technical point of view, he had the broadest range and knowledge of the various areas, from opticals to mechanics and electronics, but he didn’t like to push people. He was the kind of person that likes to tinker with his cars, go scuba diving, and do motorcycle racing out in the desert. He pals around with those guys a lot; they were a big family. All of ILM had that college fraternity feel.”

“I’d say about 125 people passed through here,” Dykstra says. “We didn’t fire many people on the show; we did lay a lot of people off, but we didn’t have too many personality conflicts. But it was pretty scary, bringing it all together, because I’d never had anything like that before. You get these creative people together and one guy says, ‘I’m going to bite your head off.’ And the other guy says, ‘I’m going to kick …’ Someone would come downstairs and say, ‘Up in roto—they’re killing each other.’ So I’d wait until the ceiling would start pounding, and then I’d call up and say, ‘Get down here!’ ”

To remedy the situation, Lucas decided to look for an experienced production supervisor—something that would also partially appease the execs at Fox, who were putting a lot of pressure on the production. On June 25, 1976, the studio had released The Omen; it was doing well at the box office, which took some of the pressure off Star Wars, but nowhere near all of it. “Fox’s production department was continuously harassing us,” Kurtz says. “Because they were as uneasy as we were. They didn’t see any paperwork to tell them what we were doing. On a normal production schedule, you know exactly where you are. At ILM, we had nothing. We had no schedule. The only way we could placate Fox was to invent paperwork.”

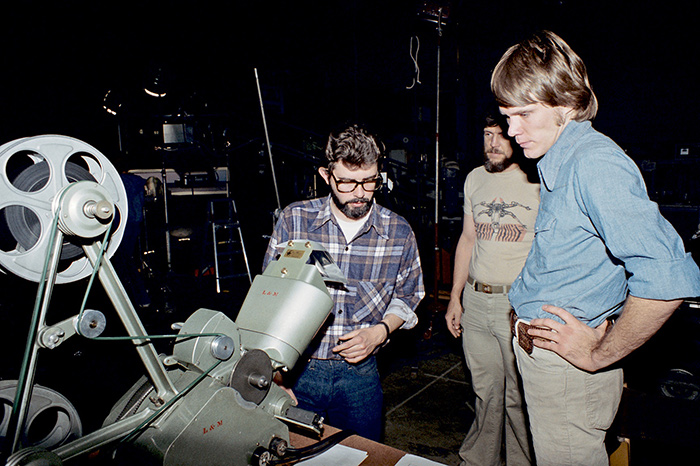

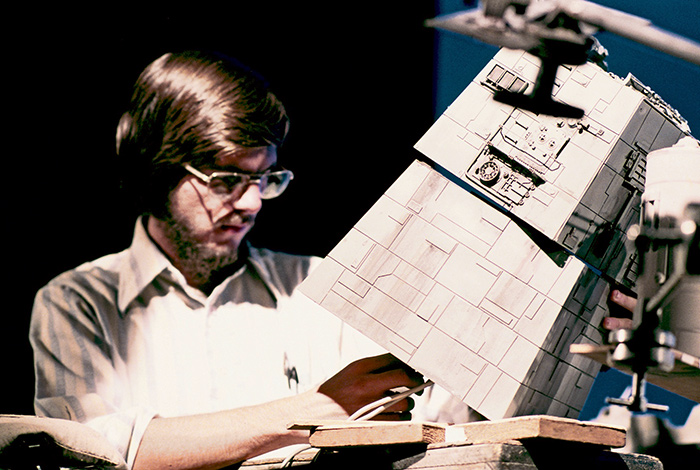

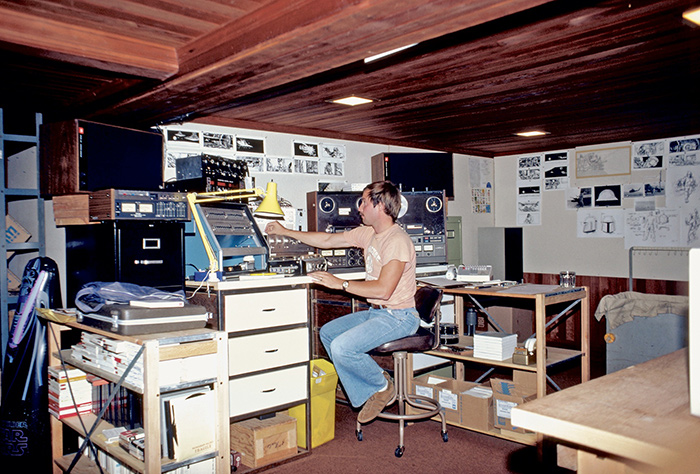

Richard Chew uses Lucas’s Steenbeck editing table at Park Way.

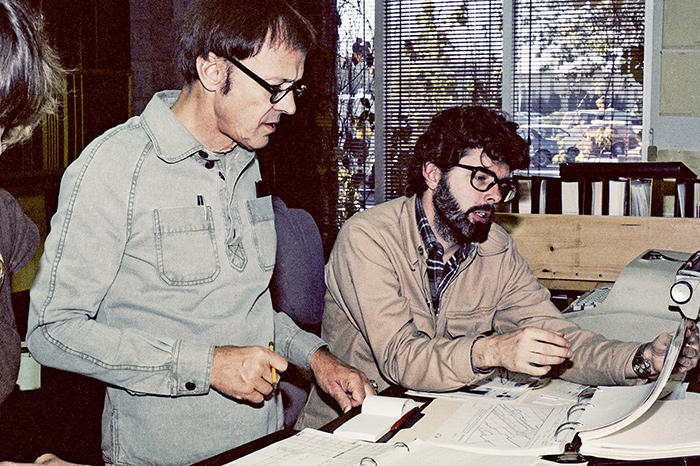

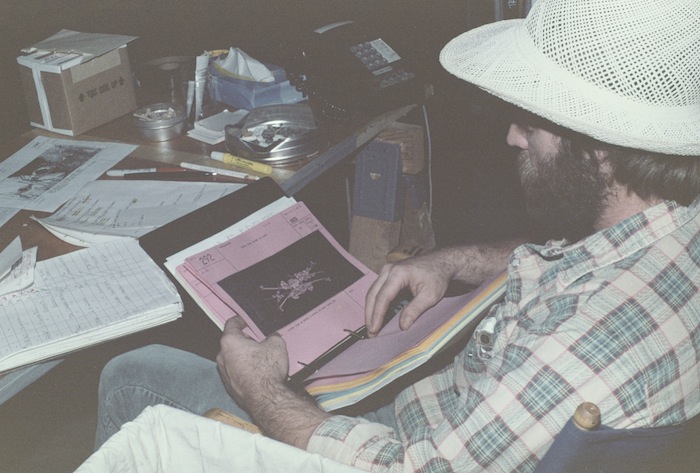

In an office on the ground floor of ILM, Lucas goes over storyboards with his new production supervisor, George Mather. Lucas’s hire, Mather put into place key reforms at the struggling facility.

It was decided that ILM’s “average” would be five shots a day. Shots were numbered and divided into categories—complicated, medium, simple—and a percentage system was worked out. By September 18 ILM was at a somewhat fictional 10-percent-complete mark. “It was the only way that Fox felt a little more at ease with what was going on,” Kurtz says. “We were having a terrible time.”

In late September, Lucas hired George Mather as the new production supervisor at ILM. “Then we really pushed very hard and whipped the place into shape, from a production point of view,” Kurtz continues. “From a technical point of view it was fine. They had worked out the bugs in the camera, the bluescreen process had begun well, both optical printers worked like gangbusters—they were raring to go. It’s just that they should have been in that spot three months earlier.”

“Mather was brought in by Twentieth or whatever combination of powers,” Dykstra says. “But it was an unnecessary hindrance to my work and my communication with George.”

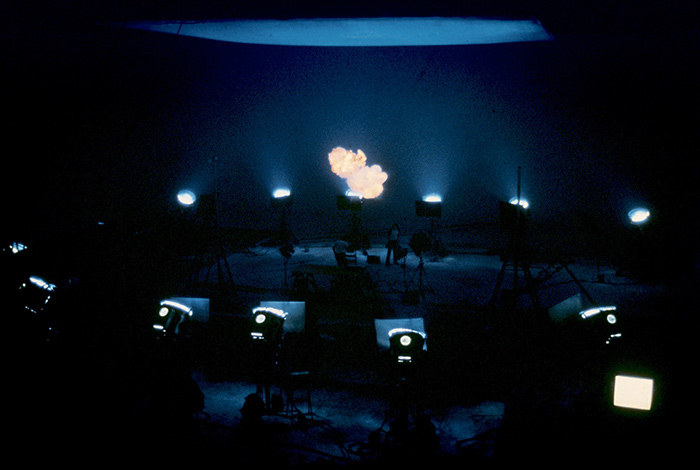

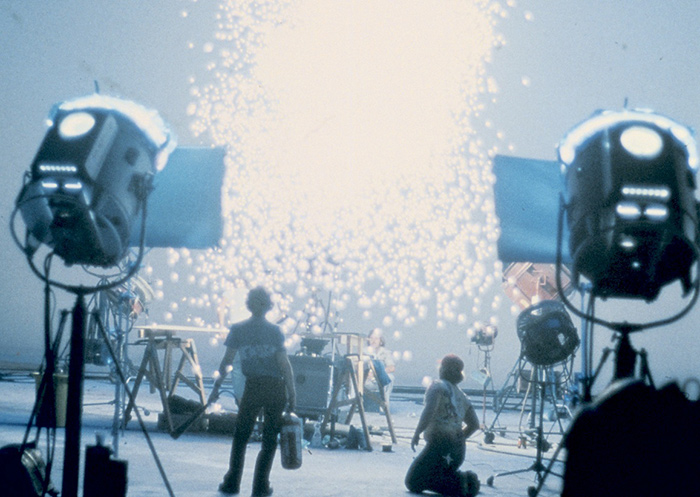

Additional specialists were hired to placate the studio, but also because ILM’s explosion tests hadn’t worked well. Having sat in the audience so many years ago and heard Lucas announce his intention to make The Star Wars, it must have been a thrill for Joe Viskocil to join the production. He and Bruce Logan had formed Nine-Ten, an ad hoc special effects house, and they were employed in mid-September 1976 to destroy miniature ships in a convincing and spectacular fashion. They also were tasked with trying out alternative-method effects shots. Logan was yet another from the class of 2001, having worked on that film as animation cameraman, animation artist, model builder, and shot designer for more than two years.

“Nine-Ten was formed when things were going pretty laboriously at ILM, in terms of what was being turned out, and there was pressure from Fox to produce more footage,” Logan says. “I think George wanted to try a lot of ideas that were different from what was happening. It was a very experimental setup, an attempt to do some things in a simpler form to expedite the huge number of shots that were needed. They were looking for eleven-frame cuts, or nine frames of this or that. Just flashes through the frame to see how it would integrate with what ILM was doing with the repeatable camera—plus explosions, which was not the main function at the beginning. But it did turn out to be the main contribution of Nine-Ten.”

Logan, Viskocil, and their small crew started on Borendo’s stage, which was quickly deemed too small for the noxious chemicals they were using. The group therefore moved to the Producers’ Studio, where additional space enabled them to set off bigger bombs at 100 frames per second instead of 300, using a VistaVision camera. The size of the detonated models also went from around three feet in diameter to about six feet.

“John Dykstra showed me the data of what they’d done at ILM,” Viskocil says. “They’d used a lot of acetylene bombs, so it was mainly sparks and the disintegration of the model. It looked very cartoonish, which wasn’t what George wanted. But through Greg Hauer at ILM, I was able to do the explosions legally because he had a powder card.

“George wanted the outline of the ship to be on fire, the entire outline of the ship sparking away, and then it would blow,” Viskocil continues. “Figuring out how to do that took some time. Finally, I used just a paste—a special blend that I made up and applied right to the model—and that would be set off first. You would then have the outline for quite a few feet of film, a few frames, and next you would blow it up. George wanted to see the fireball effect, the World War II type of footage where the ship just disintegrates and you see this big ball of gasoline flame. One thing that I appreciate George for is the fact that he just gave me full rein to do what I wanted. He gave me a concept as to what he’d like to see, and I just elaborated from that.”

Nine-Ten decided to use mainly silt, magnesium, and gasoline-based explosives, electronically detonated with squibs. “We had only one day to shoot something like eight or nine X-wings and Y-wings exploding at the Producers’ Studio—and it was really something!” Viskocil says. “I remember we all came in Saturday: Terry Bowen, David Lester, Brent Bryden, Jerry Deets, Mike Myer. It took a lot of time to actually put all the explosives in the ships and prebreak them and wire them up. We didn’t test out anything. We went for the shot—and we were lucky.”

At one point pieces went through the ceiling, and at another Viskocil burned his hand. “I did have a little flaming debris on my arm at one point,” Logan says, “but I was able to put it out with the fire extinguisher.”

Nine-Ten did seventeen days of work—seven at Borendo and ten at the Producers’ Studio—with a crew of eight people. The results were successful, but they did run over budget, costing over $65,000 instead of the projected $35,000. Logan and Viskocil would later work at ILM, however, using their experience to help create additional explosions.

Other outside houses, such as DePatie-Freleng Enterprises and Ray Mercer & Company, were also used from this point on to complete certain shots for which ILM was not equipped. Located on West Cahuenga Boulevard in Hollywood, Van Der Veer Photo Effects worked on the animation for the laser bolts and lightsaber effects (about thirty shots, according to Blalack), while Modern Film Effects composited 35mm anamorphic footage taken in England with VistaVision elements created at ILM.

At Nine-Ten an air cannon is used to enhance an exploding X-wing.

On September 14, 1976, Lucas sat down with Charles Lippincott for his first extended interview since before principal photography. The answers to the questions (here organized by subject) are spoken by a man who is clearly exhausted and somewhat disappointed about much that had passed and much that was still going on. But it’s possible that, like the earlier interview that took place after the green light, this one was related to the signing of the long-awaited contract.

The long shot during the escape from the Death Star of the TIE fighter blowing up: “That consisted of two separate explosions shot off at the same time, so it looked like one was coming through the other,” says Joe Viskocil. “Alderaan blowing up was a gas explosion that consisted of wood fibers,” he adds. “The pieces of wood would silhouette to give the feeling of the core of the planet.”

The studio: “Fox still doesn’t know what the film is. They’re not a model of confidence. They’re still worried that they’ve got a big and expensive ‘something’ on their hands, which they can’t describe or understand.”

ILM: “Given another five years and another $8 million, we could get some pretty spectacular effects out of there. But we don’t have the time or the money. I don’t know what else to say. That’s the biggest problem.”

Principal photography: “After trying to improve the script and trying to find the right story, the movie became itself, it took over. It was very hard. It found itself and became the movie that we were making. It wasn’t particularly the movie I started out to make.”

Concept: “When I came up with the idea for Graffiti, it was astounding to me that nobody had ever done it. I just could not believe that nobody had ever done a movie about cruising, one of the top national pastimes. Same thing here: It’s inconceivable that they aren’t making hundreds of these adventure movies. It’s part of American culture.”

Visuals: “The thing I like about this film is the fact that it was written and designed as a movie. The elements that are interesting in it are cinematic elements, not literary elements. It was designed as an emotional, visual exercise, not as an intellectual exercise. I’m sure we are going to get a lot of backlash because of that, but I’m not afraid of it being called a comic-book movie.”

Predictions: “Star Wars could be a type of Davy Crockett phenomenon. I don’t know whether I’ve done it. I don’t know … But I know I’ve got a better one in me, one that is more refined. Gene Roddenberry wrote about his Star Trek series, and pointed out that it wasn’t really until about the tenth or fifteenth episode that they finally got things pulled together. You have to walk around the world you’ve created a little bit before you can begin to know what to do in it.

“Someday I’ll do another movie like this, maybe, which will be much closer to my original plan. I didn’t get the illusion that I’d seen in my mind. I got something else, which is all right, but wasn’t what I started out with. Whenever you make a movie, a force takes over and directs the movie, and there’s nothing you can do about it. It takes on its own shape. It’s chemistry, the chemical reaction between people; the wind and the weather, and everything. All that has its own influence; it all has a life of its own.

“The film’s only hope is that it is Jaws and not Godzilla versus the Gila Monster.”

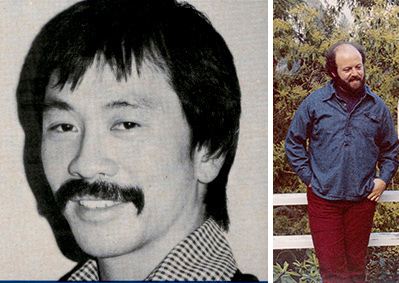

Richard Chew was the second editor hired, while Paul Hirsch was the third.

With director Brian De Palma, Hirsch attended a dinner (standing: Hirsch, De Palma, and Hirsch’s wife, Jane; sitting: Verna Cocks, Lucas, Jay Cocks, and De Palma’s future wife, Nancy Allen).

Hirsh also attended a discussion with Steven Spielberg (in cap, with Hal Barwood on the railing. De Palma, Kurtz, and Lucas).

Lucas’s feelings about his film made themselves felt as he began the constant shuttling back and forth between his Park Way offices in Northern California and his special effects crew in Southern California.

“I recall one comment he made when he was having a hard time with one of the scenes that I was cutting,” Richard Chew says. “I could tell that he was really unhappy, but I couldn’t tell if he was unhappy with what I was doing or with the film. But George admitted to me that all he could see were his mistakes every time he looked at the scene, that it was like free association for him. He remembered all the traumas he endured while working in England: the day so-and-so had a cold, or someone had a sore throat and this guy was late, and that lens broke or he had to use the lens that he didn’t want to.

“Plus, he had dozens of people down at ILM, where he was spending three days a week, and then he’d come back up north and he would look at something and say, ‘Oh, this doesn’t work—did I mess up in directing this?’ It was just another straw on his back.”

Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins, whose offices at Park Way were a stone’s throw away from the editors, were witnesses to the process. “Matthew and I would go to lunch with George frequently,” Barwood says. “We’d go down to the carriage house at about lunchtime and George would be sitting there with the Moviolas, cutting away, and every now and then he’d say, ‘Hey, take a look at this.’ One day we saw Princess Leia with this sort of cardboard gun, peeking out, and then a coupla guys in these plastic suits that looked silly said, ‘Set for stun.’ Matthew and I walked outta there and had a wonderful lunch with George, and when we went back to our office, we joked around for about an hour saying, ‘Set for stun. Set for stun! Oh my God, it’s a disaster!’ ”

Despite his feelings of despair, Lucas forged ahead and was often able to aid Chew by recalling the best line readings of a given scene. “At the end of the week, he would spend all his time just looking at what we’d done while he was at ILM,” Chew says, “and then looking with us at what we were going to do the following week. Usually we’d approach a scene by looking at the dailies. He would tell me what he liked, and then I would make something out of that. He has a very good memory, so we almost never had to go through the outs [discarded dailies]. George would spend anywhere from a half hour to a couple of hours appraising each scene.”

But even with two editors, work was not proceeding fast enough. According to the postproduction calendar in the long-form contract, they were more than a month behind. Brian De Palma had heard they were in need of help, so he recommended his New York editor, Paul Hirsch, whom Lucas had recently met in Los Angeles, but who was now back home.

“Marcia Lucas called me,” Hirsch recalls. “And she said, ‘Things are going a lot slower than we had hoped; our editor in England didn’t work out and we’re having to recut everything. We’ve got Richard Chew working on the picture—but we’re just not getting enough done! Are you available to come out?’ And I said, ‘My wife is expecting a baby, but let me ask her.’ The timing was crazy, but I went home to Jane and said, ‘I’ll understand, whatever you say: I have an offer to go out and work on Star Wars.’ And she said, ‘Go do it.’ ”

A former architecture student at Columbia University, Hirsch had opted instead for film, so he dropped out and found work at a “trailer house” that had the MGM and United Artists accounts. His first mini success was when he cut down a ten-minute featurette on The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) to three and a half minutes. Before leaving for the West Coast, Hirsch had to spend a week finishing up on De Palma’s Carrie, arriving in San Anselmo on October 16. “I was a little intimidated,” he says. “Because both Marcia and Richard had been nominated for Academy Awards before, and I was just this kid from New York, but they were great.

“At first I was working on the Moviola. But I had forgotten how many years it had been since I had worked on one, so I was all thumbs, breaking the film, dropping it, and wasting a lot of time just trying to get the film to go through the machine. So Marcia said, ‘I don’t care. I’ll work on the Moviola.’ After that, I was working upstairs in George’s room on the Steenbeck.”

Hirsch’s first encounter with Lucas in the small carriage house was instructive. The editor was given a scene that Jympson had assembled that seemed to already conform to what the director said he wanted. “I was overcome with a great feeling of dismay,” Hirsch says. “It seemed to be exactly what George was after. But he said, ‘This is your test.’ So I started to get into it, looking at alternate takes and really examining the possibilities of the scene. The original scene had been cut to about four minutes; when I finished the scene, it was down to three minutes—but there was more in it.”

Once Ben Burtt understood the lay of the land, he, too, grabbed a room at Park Way, in the main house basement. “I got to know George better since I was near him,” Burtt says. “He told me, ‘We’re going to start editing the picture. What I want you to do is just start cutting in sound effects that go with the picture so I can see whether I like them or not.’

“I was alone in a room with the sound equipment and the library. So the first day I walked over to the editors and I asked if could see the reels they’d cut, so they ran reels one and two. It was the first time I’d seen anything in the picture, and I was overwhelmed. When they were finished with those reels, I just took them back and the first thing I started working on was the big fight in the beginning. There was no spaceship shot, no titles, so I started working on different laser gun sounds. I worked with the basic laser gun sounds for about a month. At the same time, I started working on Artoo-Detoo, since he spoke right off the bat.”

Lucas would fly down to Los Angeles every Monday and work at ILM until Wednesday evening. Slowly, over a period of months, he was able to put things together and become better acquainted with the personnel down south, though stress levels remained consistently high. According to the fictitious but—judging by ILM’s internal reports from the time—strangely accurate estimate put together by Kurtz and Mather, 18.1 percent of the effects work had been completed by October 16.

“When George came back from England, we’d been operating autonomously for some time building the equipment and learning how to use it,” says Edlund, whose first job had been working at CBS News, out of Seattle, Washington, as a television cameraman—this after graduating from UCLA with a philosophy degree and dropping out of Harvard Law School a few years later. “But George wasn’t satisfied with the look of the shots we’d done, so he spent some time with me on the stage. I would program a shot, so that he could see all of the parameters, and he’d say something like, ‘It looks like it pans a little bit too much, can you fix that?’ I’d correct the pan, then shoot it in black-and-white, develop it here in fifteen or twenty minutes, and put it on the Moviola. George could see exactly what we’d done, and he’d say, ‘That looks better, but let’s do this.’ On two or three shots, we went over it ten times—but it was great, because after that point, if I had a problem, I could call him if he happened to be in San Anselmo, and he knew what I was talking about. The telephone became a successful communication device.”

“We finally got up to sixteen people in the optical department, working on two shifts, eleven hours a day, six days a week,” Robbie Blalack says. “After about six months of testing and playing around, we got the process of printing from the bluescreen shots and all of the other elements down to where it was fairly good.”

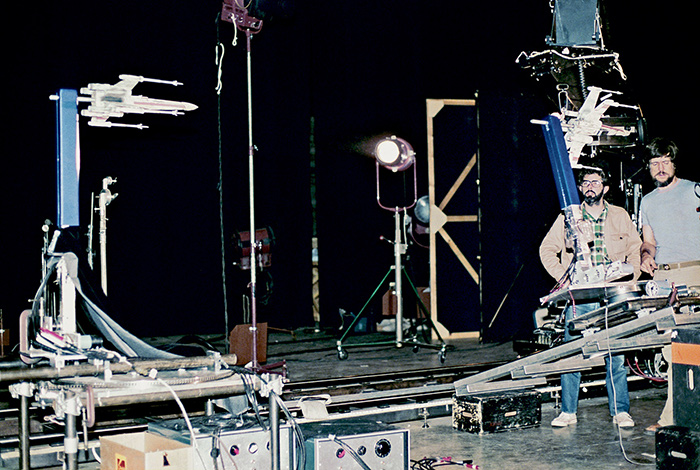

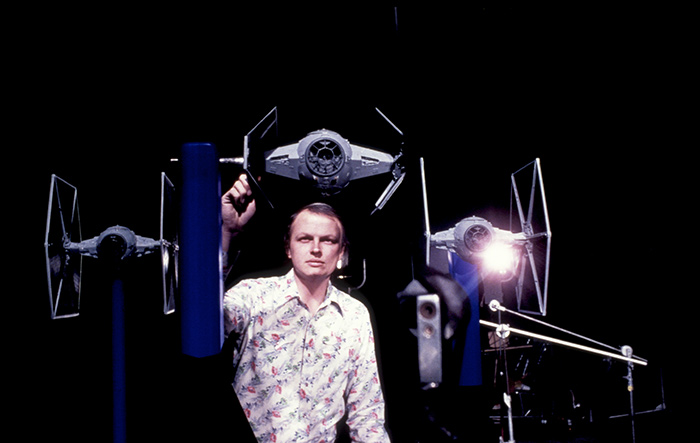

On one of the stages at ILM, Edlund and Lucas talk.

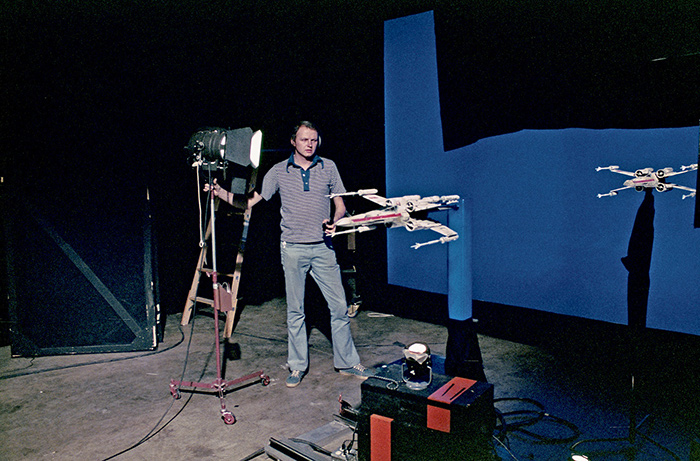

Edlund and Lucas with X-wings supported by blue pylons—one of Dykstra’s innovations that greatly facilitated the bluescreen process.

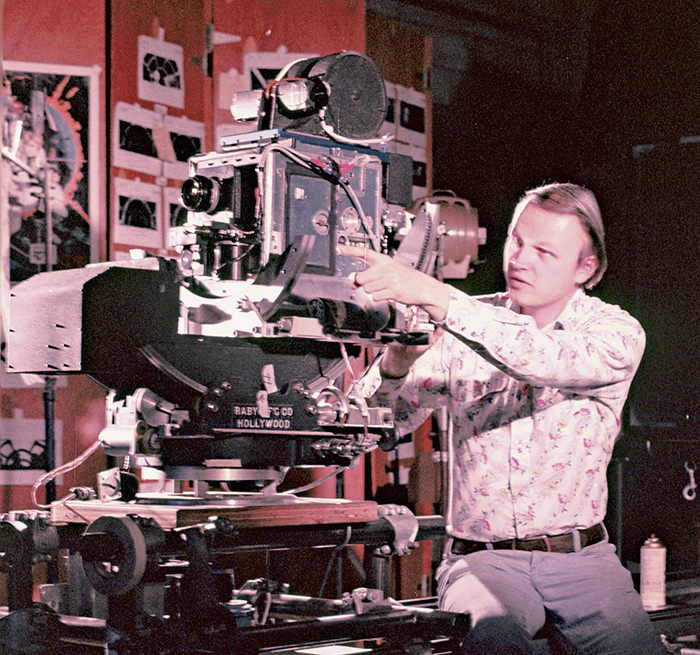

Standing around a Moviola, Lucas powwows with Joe Johnston, who designed the T-shirt being worn by Edlund.

T-shirt design by Joe Johnston.

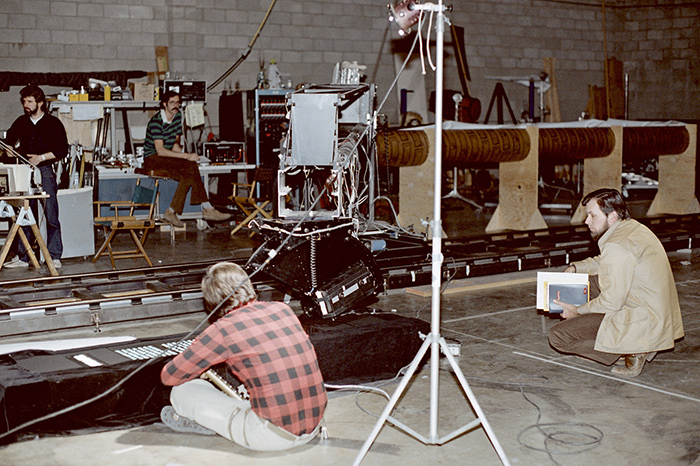

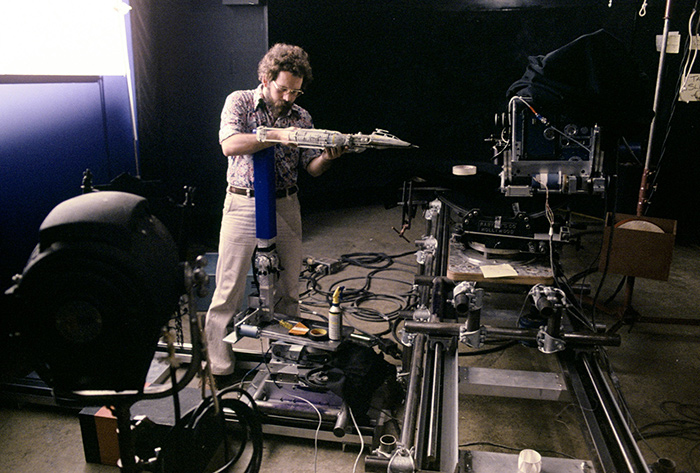

One shooting stage had the Dykstraflex on a 40-foot track with its boom (with Lucas, Paul Huston on stool, and Kurtz kneeling). The second stage had a 14-foot track with a Technorama camera. Both stages were equipped with turntables, motorized trolleys, and bluescreens.

To do the “lineups,” Blalack hired Dave McCue, John Moles, Bruce Nicholson, Donna Tracy, and Eldon Rickman, who had been recommended by Disney—all young people ready to work very long hours. Jim Vantress, who used to run the insert department at MGM, was brought in as an “operator,” as was David Berry, who was imported from the stage area. Much of everyone’s concern was keeping the printing room ultraclean so no dirt would contaminate what had to be an always pristine negative; eventually a vacuum suction machine was purchased that could suck up dirt from people’s shoes.

ILM’s change of course continued as Bob Shourt managed to remedy R2-D2’s mechanical problems in two weeks, much to Lucas’s relief—something John Stears’s special effects department hadn’t been able to accomplish in six months. George Mather also had a small but crucial first victory when, according to Lorne Peterson, he was able through his Hollywood connections to speed up the time in which ILM’s VistaVision film was being developed; up until his intervention, the processing houses were apparently ignoring the low-level production.

“They needed to get the film done in time,” Dennis Muren says. “I tried shooting some spaceship shots on our older secondary camera, but eventually the decision was made for me to work nights and Richard Edlund to work days on the main camera, starting in August or September, for about five months.”

“George was our general,” Muren’s assistant Ken Ralston says. “We were his soldiers and we were all fighting this single battle to get the film out.”

As shot production increased, and more shots were approved by Lucas, the sixteen months of preparation began to pay off. “There wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm until the people around this organization started seeing some product,” Dykstra says. “And then they would go, ‘Hey, look at that, that’s pretty neat.’ ”

The comments, offhand in August and September, became more deeply felt by October, and the place began to really gel. It had begun with an odd combination of people with specific talents, many of whom had never been involved in filmmaking before. Finding themselves in a situation where they could apply their distinctive creative abilities to a unique purpose, they now realized they were learning quite a bit, which, in turn, inspired them to put even more into their work—to the point where they actually started to compete for extra duties.

“We hired renaissance people who understood enough about film and drawing, about mechanics and carpentry, and who could interrelate,” Dykstra says. “But all of a sudden we had people going, ‘That’s my responsibility, you’re taking my responsibility!’ And it gets to be a knotty problem keeping everybody happy. It’s the first time you ever found people arguing about taking more work, right? These guys were crazy, but it was a nice switch.”

ILM was often dealing in contradictions. Outsiders saw the effects house as disorganized because it was unorthodox, but internally everyone knew they were under duress and on a timetable. The paradox worked fairly well, led by the department heads who, by this time, were working together harmoniously. “Those people—McCune, Blalack, Edlund—came in all at once so that they could develop their own spaces and a method of communication. There were no memos, not one single memo pad,” Dykstra explains. “There were memos to the outside world, but the information that was done around here was done by word of mouth. The people upstairs knew what was happening on the stage and the people on the stage knew what was happening upstairs. There were problems, but overall it worked really smoothly. It could’ve been a lot worse. Not one person killed anybody else, although it came close a couple of times.”

The noncorporate way of working added to ILM’s mystique and people began to call it the “Country Club.” Because the facility had no air-conditioning and the temperature on the two stages often rose above 100 degrees beneath the hot lights, a makeshift cold tub was constructed outside. Filled with overheated longhaired employees, it was eyed with horror by visiting studio executives. Another way to cool down was provided by Joe Johnston, who purchased an airplane escape chute from a manufacturer across the street and transformed it into a water slide. For relaxation, the model shop was used for dances, and film nights were scheduled with pizza (and the occasional porno film snuck in). A Friday-evening tradition became known as “launching ship night,” because ILMers would take model rockets and blast broomsticks, old X-wings, plastic models—and once an old car—as far into the sky as their rocket fuel would carry them.

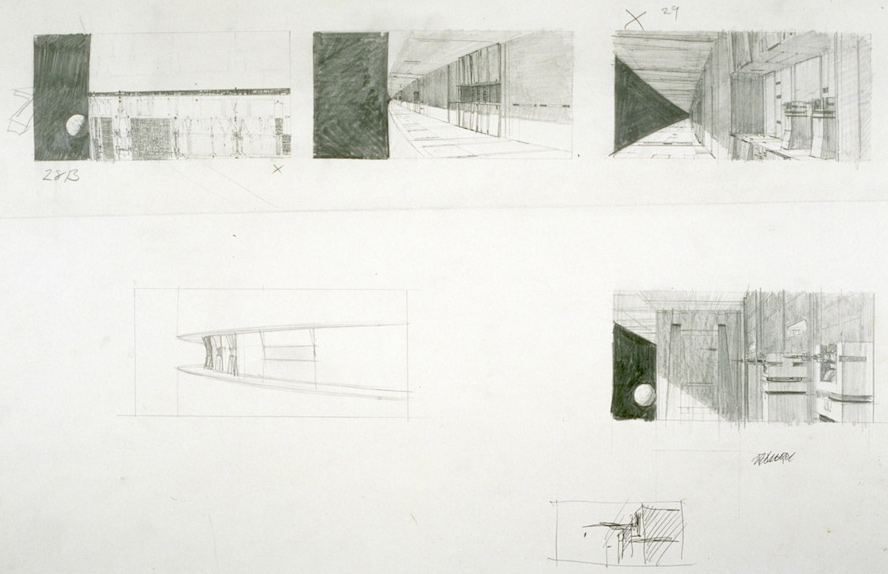

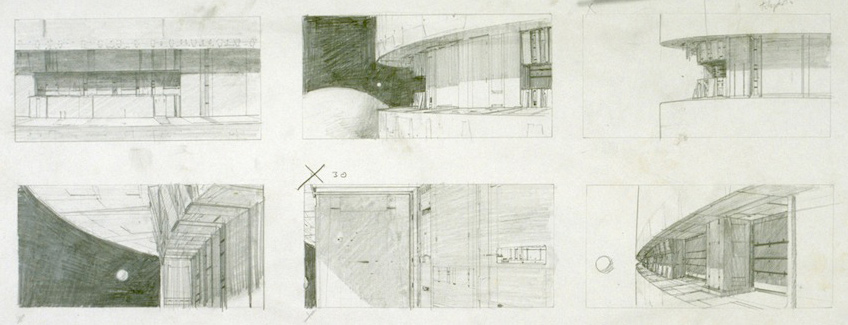

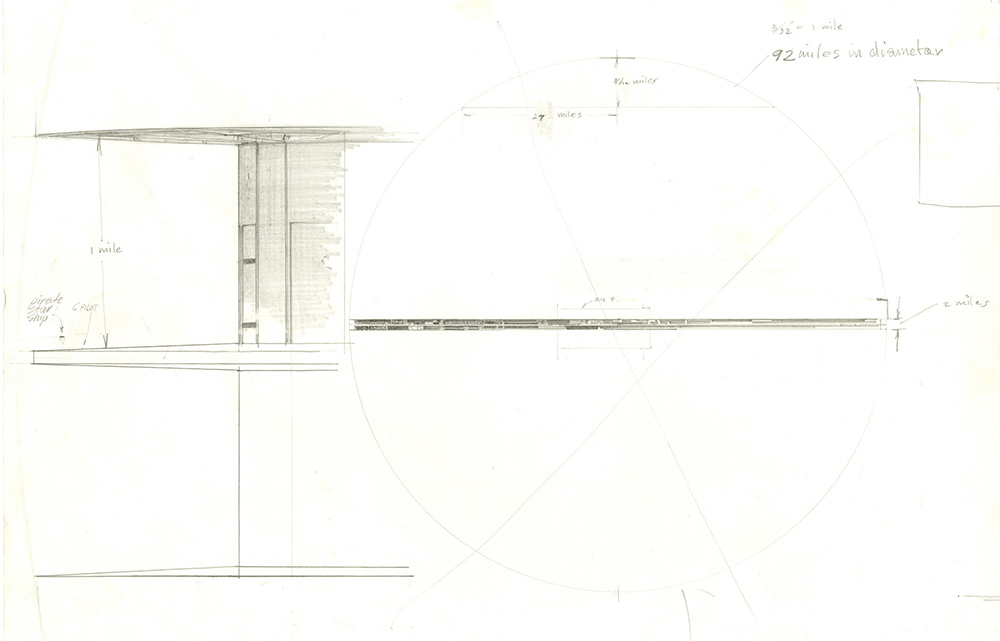

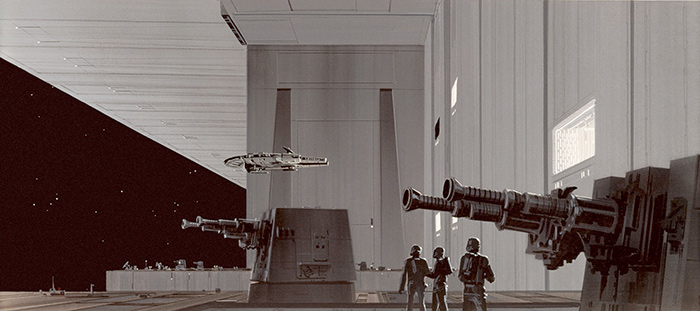

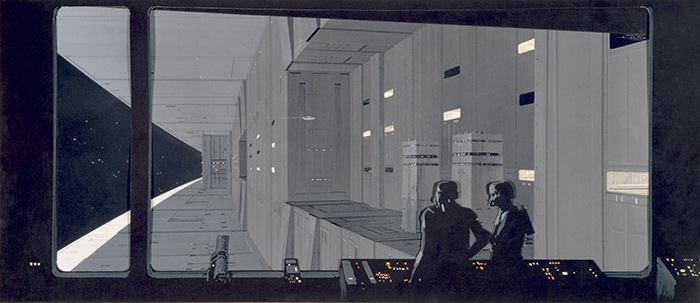

Sketches and an early version of a Death Star matte painting by McQuarrie. In one drawing he notes that the Death Star is 92 miles in diameter, its equatorial trench is 2 miles wide, and so on.

The atmosphere during working hours was deceptively calm, however, as much of the photography was done late in the afternoon or at night. The facility literally didn’t have enough electricity during the day at times, because of industrial plants down the street that tended to hog the neighborhood’s resources. Once the factories closed at five, shots lined up during the day could be completed. A lot of people therefore slept on the premises, with their sleeping bags on cots, in a state of enthusiasm mixed with high anxiety.

“People don’t understand this and I doubt that they ever will,” Dykstra says. “If you do special effects, you work in a black room all day long and you get totally paranoid about your film. Everything happens slowly and you can’t tell if there’s a glitch in the shot until you get the process back the next day. People are on edge a lot and under pressure all the time.”

By October 30 ILM was up to the mirage-like statistic of 25.8 percent complete. But they were making progress, and Lucas’s feelings had gone from almost entirely despondent to somewhat hopeful. “I remember George visiting my house in Los Angeles,” Martin Scorsese says, “and complaining about the special effects and how he never wanted to direct again. He said he’d really had it. But he was thrilled with certain shots, like a spacecraft crossing the frame and the camera panning with it.”

“George was the only one who had seen the whole picture,” Paul Hirsch says. “I had no idea what the stuff looked like and wouldn’t know until I finished the reel and got into the next reel. I was trying to do about a reel a week because of the time pressure. I’d finish a reel and go to George, and he would discuss what I had done and we’d make changes and get it right. Then I’d go on to the next reel—and it was just a whole world. I remember looking at reel nine with George—which has Ben going into the power trench, then the Tarzan scene, with Luke and Leia swinging across the chasm, and the swordfight and the shootout when they escape—and I looked at that reel and I thought, My God, this is going to be a lot of work.”

“I was working with three editors at once,” Lucas says. “I was spending half of my time in Los Angeles working on the special effects, so I could only work with them for three or four days a week. I would tell them what I want, say this is the shot that I want, and this is the way I think the scene should work. Then I would come back the next day, look at what they’d cut, and we would discuss the changes and problems. I was going from editor to editor to editor, all day long.”

As the editors went as fast as they could toward a first cut, with Hirsch working upstairs and Marcia and Chew downstairs near the assistant editors and the coding machine, both Chew and Hirsch were able to assess Lucas’s editorial style. “George likes to keep things simple and gets his energy from the cutting,” Hirsch says.

“He was pretty spare,” Chew observes. “Coming off Cuckoo’s Nest, it especially struck me. Milos Forman would have four or five printed takes of a master; then he would have the singles and the two-shots, and four or five takes of those. George, either for aesthetic or budgetary reasons, was much more controlled about that.”

Although there were certain scenes that each editor “owned,” they began to trade off just before completing the initial cut. “We put it all together and then spent about three or four days as a tag team,” Hirsch says. “George, Richard, Marcia, and I would sit at the machine each for a couple of hours, taking turns and making suggestions. The last day, we did this for about twelve hours.”

From the aggregate interviews, it’s not clear exactly when the first cut was finished, though it was probably late October or early November. The scene chronology of the first assembly corresponded almost exactly with the shooting script, with Biggs, Luke’s friends, Jabba the Hutt, two trench runs, and so on. Those who saw this cut, either together or at intervals, were Lucas, his three editors, Kurtz, and Burtt, who had done a “scratch mix.” Temporary sound effects thus accompanied the whole picture, but it had only scattered special effects shots, primarily from the Death Star escape sequence.

“At that time very few optical shots were completed from the end battle,” Burtt says. “But they had a work print based on old World War II movies. So I cut the spaceship sounds and lasers to that. We had Spitfires going by that sounded like spaceships; we had lasers being fired from Messerschmitts. It was relatively insane.”

“I’d always seen the film in bits and pieces, only the parts that I was working on, or looking over someone’s shoulder,” Chew says. “So the most lasting impression I have of the film was after watching the first cut the first time—and when I saw it, I was really astounded by the entirety of George’s vision. I don’t think I was able to get up from my chair afterward for about ten minutes in the screening room. I realized the look of the film, the thrust of the film, the characters of the film were so uniquely George—if you know George in any way, you had to realize that all of this came as a result of this one man. And it just knocked me out. It was coming from the recesses of George’s mind, this basic seed that he had grown into a thousand trees.”

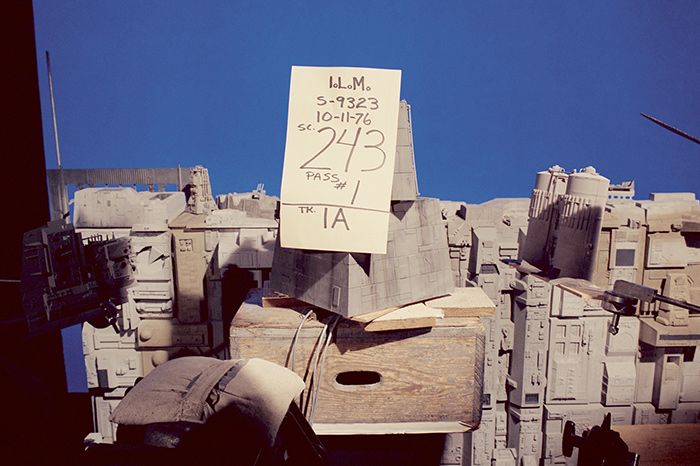

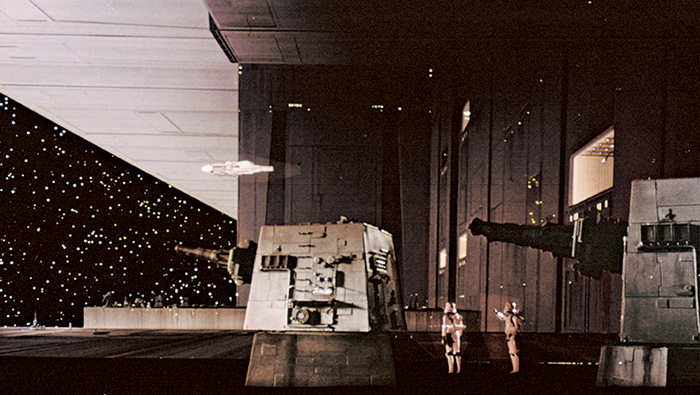

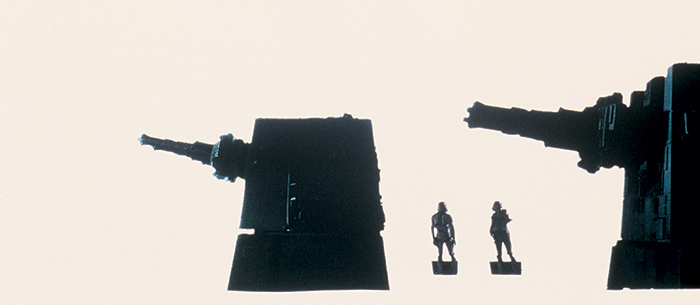

A Death Star trench canon bears a note with the date October 11, 1976—the day that George Lucas officially approved the first ILM shot.

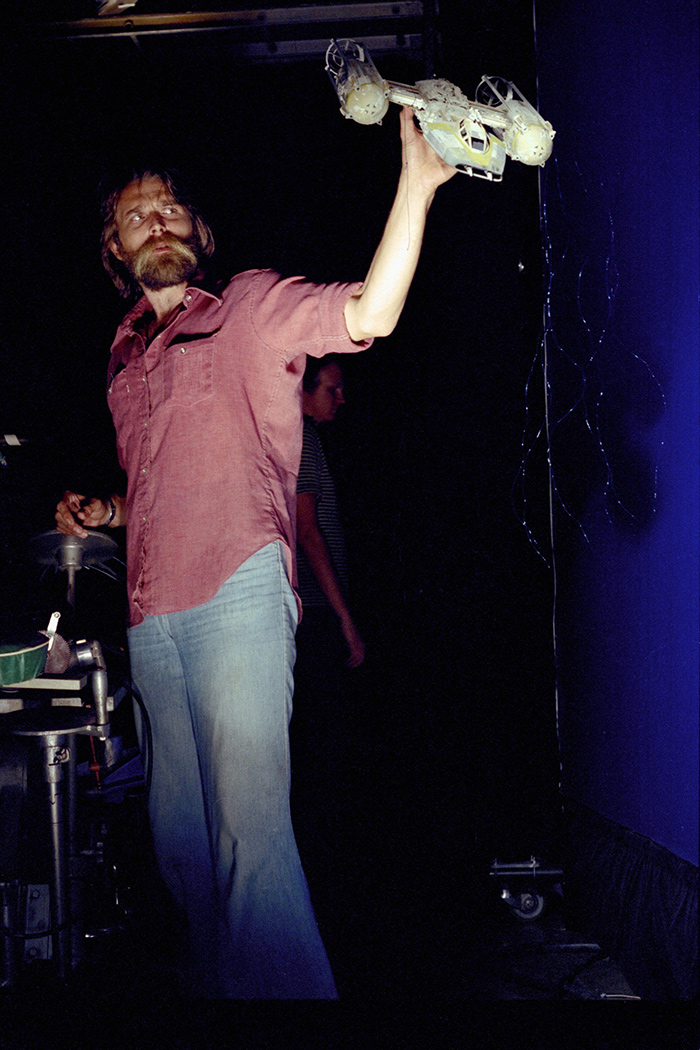

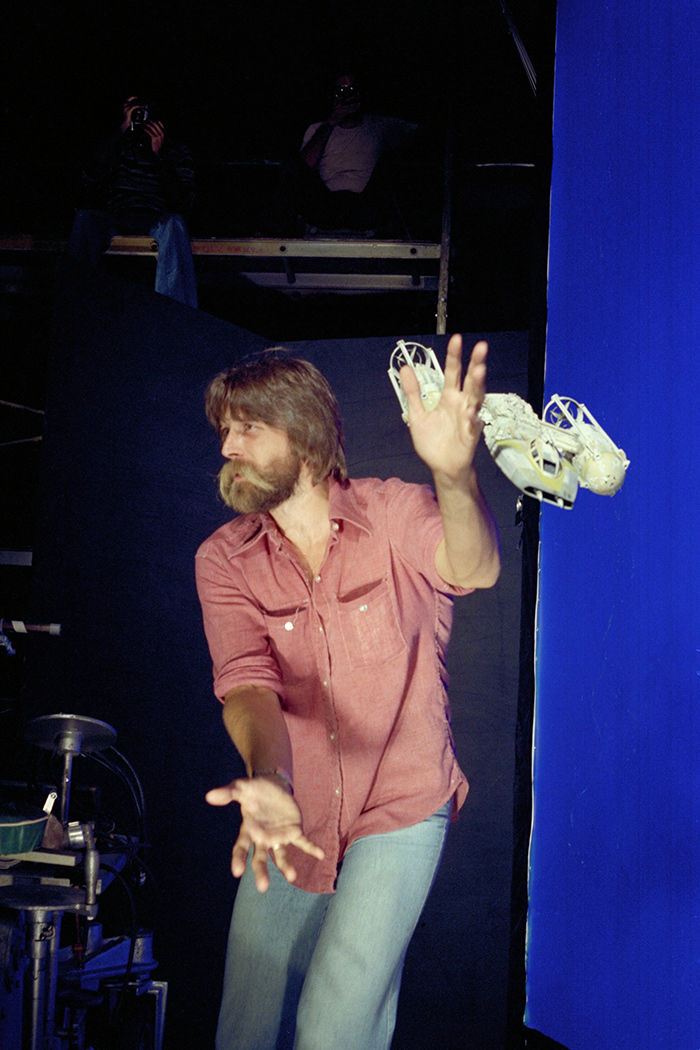

Ken Ralston used the same tower when helping photograph elements for a complex shot of the Millennium Falcon being pulled into the Death Star.

McQuarrie’s production illustrations were the guide, as Lucas directed second unit (below). “When the Falcon is drawn into the Death Star, that’s a matte shot with a number of elements,” Richard Edlund says. “That was actually Joe Johnston down there in the foreground—in fact, it’s Joe Johnston and Joe Johnston. We only had one Imperial suit at that point, because the other had been stolen, so we shot it split-screen. We also needed two canons, but we only had one.”

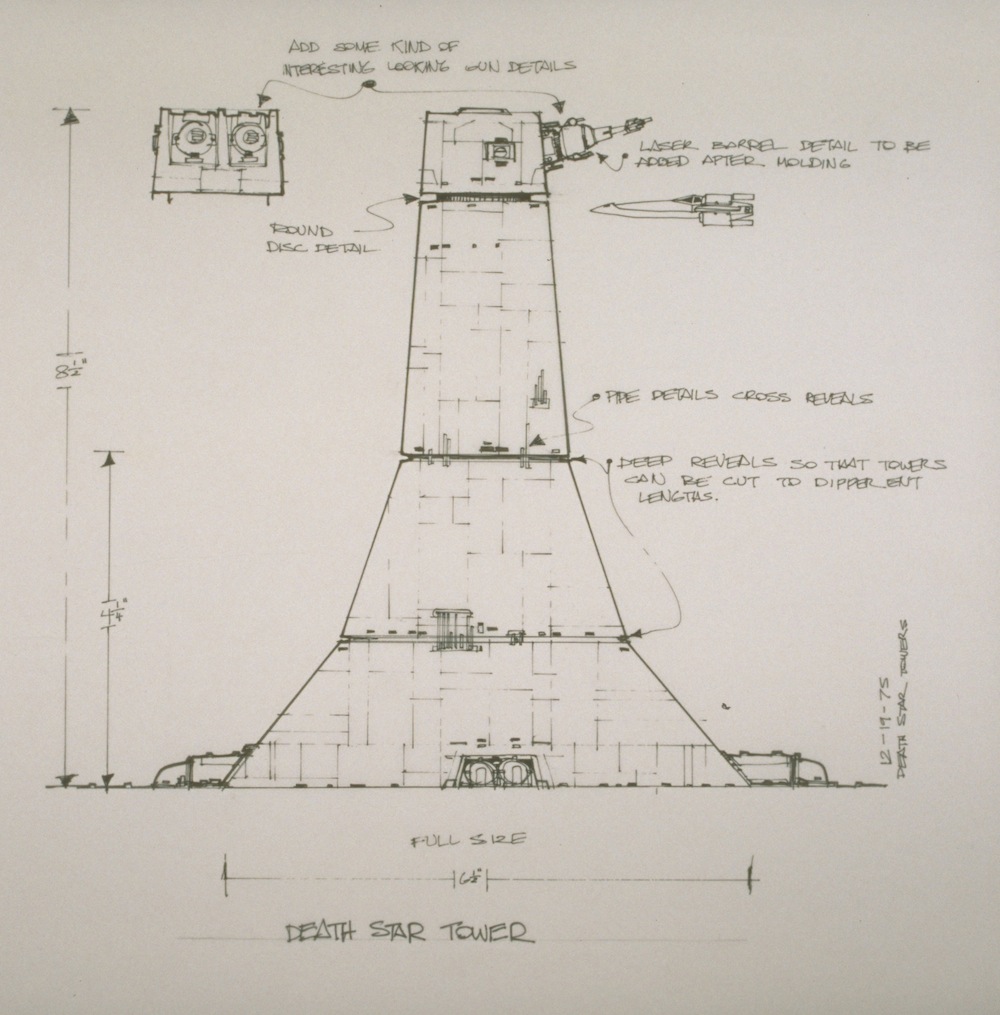

Death Star towers and laser cannons concept sketches, by Johnston.

Chew was evidently impressed, and the others could also see the film’s potential. But it was very far from finished, and the screening led to several changes and two substantial cuts. First Lucas decided to begin the movie the way he’d written it in his second draft, before intercutting the scenes of Luke and his friends on Tatooine with those of the robots, Darth Vader, and Leia in space.

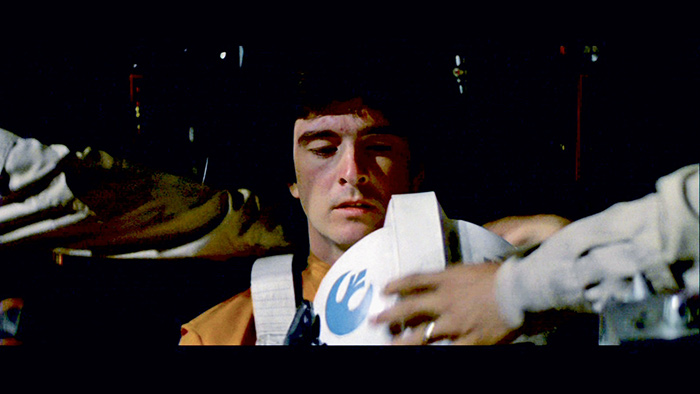

“In the first five minutes, we were hitting everybody with more information than they could handle,” Hirsch says. “There were too many story lines to keep straight: the robots and the Princess, Vader, Luke. So we simplified it by taking out Luke and Biggs, instead just presenting the Princess and Vader, which is clearer. The Princess has the plans—the thing that everyone in the film is very much concerned about—and she gives the plans to the robots, and the robots go to the planet and they meet Luke. So that’s now relatively simple.

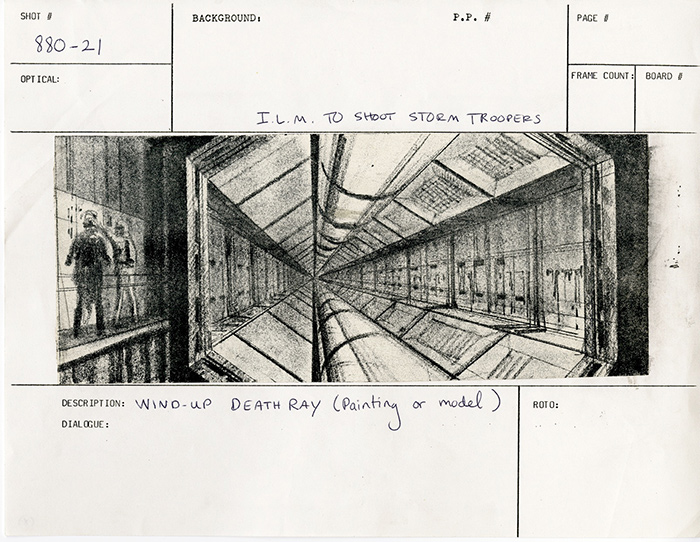

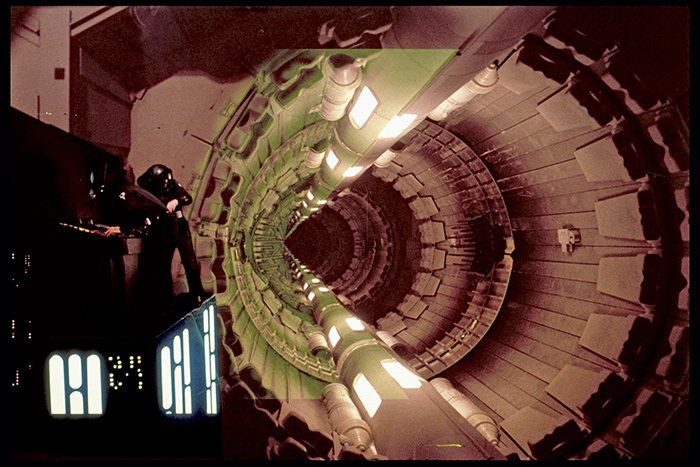

At ILM, Lucas shot inserts of Death Star technicians preparing to fire the Laser including Joe Johnston and Jon Erland as those occupying the laser tunnel (above, with Edlund holding a light meter as Lucas looks on). “That energy tunnel was fairly difficult, because it was not that easy to do circles in perspective,” animation supervisor Adam Beckett says. “The shots that did have interesting requirements received, possibly, excessive attention because of their rarity, but that energy tunnel has everything in it but the cat’s meow. It’s got light effects, a live-action element, two guys, with light effects on them. That platform is hand-drawn by Pete Kuran, who also created the light effects on the wall of the tunnel with Jonathan Seay. I’d do the key drawings and Diana Wilson would do a Lot of the in-betweens. There were probably 160 pieces of artwork in 42 frames; the only reason there are so few is because most of the animation is in cycles that can be repeated over and over again. Those concentric rings going down the energy tunnel are just repeats. The miniature of the infinite tunnel was done by cutting a hole in a front-surface mirror and photographing it through that hole with another mirror behind it—just like at the funhouse.”

“But it also made the picture a lot weirder,” he adds, “because the main characters became the robots, which is a wonderful idea. It’s very George. And the reason it works is that George invested the characters with a human sense of humor. It also made the planet they land on work as an alien place. Before, by showing Luke on the planet, there was no mystery: You knew the planet was inhabited by people. But now when you go to the planet with the robots, you don’t know what you’re going to find—the first characters you see are Jawas—which gives it a whole air of exotic mystery.”

George also felt that there was no reason to see Luke until he became an active participant in the story. But it was not an easy decision to make to just delete those sequences; Marcia fought to keep them in, and the four scenes with Luke and his friends were tried in different places. But more arguments for cutting came from the fact that George didn’t like the performances, and that the later relationships Luke creates are stronger.

“One of the big topics that came up was how do we speed up getting to the cantina scene?” Chew says. “The answer was to stay with the story of the robots, also because it’s so much more unconventional. That’s when George told Paul and me for the first time that that was initially how he had written the story. To us, who were new to the picture, that just seemed the way to go.”

The second major sequence to be cut was the scene in which Jabba the Hutt spars with Han Solo. Lucas realized that ILM would not be able to complete the complicated stop-motion Jabba he’d wanted in time to finish the movie. Again, though she knew the scene had problems and would be hard for ILM, Marcia lobbied to keep it. In this she was joined by Harrison Ford. The problem once again, however, was pacing and performance. “George also thought there were too many phony-looking green Martians that looked like Greedo in the background,” Hirsch says.

Once again, different methods for salvaging the scene were mulled over. “George considered putting subtitles under Jabba, and I think that idea got transferred over to Greedo,” Chew says.

“There were certain expositional elements in the Jabba scene—the fact that Han was a smuggler, that he was wanted, that he needed the money—so we incorporated those into Greedo’s sequence and that solved that problem,” Hirsch adds.

The first cut ran about 117 minutes. And even though they were dropping some scenes, the editors knew the film would stay about the same length because it was missing “personality” shots of the Death Star, establishing shots, the roll-up, and the credits. Indeed, so much was still in the works that Ladd, sitting in his office at Fox, was pessimistic about the film being released on schedule. The film had already been pushed back from its initial April 1977 date, and he was concerned it might slip again.

“In September, George, Gary, and I had met with Laddie, Jay Kanter, and the future head of marketing and distribution, Ashley Boone,” Lippincott says. “We told them it would be ready at the end of May. They spent a few days talking it over and called back—they agreed.”

“We met at the time to discuss it, because there had been much contemplation of not opening the film in the summer of 1977,” Ladd says. “That they were going to get October instead, because there were hardly any effects, and they were so far behind that the feeling was they would not be ready. But George said, ‘I will be ready.’ And he explained how he was doubling up on some things which would allow him to make the date.”

Around this time, Lucas also asked Ladd for funds to reshoot parts of the cantina sequence for Greedo’s new dialogue, and to enhance the scene with more aliens, but no immediate decision was forthcoming.

The scratch track on the first cut did not include finished robot sounds, because each one was a special case, and none more particular than that of R2-D2. “Discussing Artoo, George said, ‘I want an organic sound, like it was a five-year-old kid, but he’s got to sound electronic,’ ” Burtt says. “The first I did were too electronic, pure synthesizer, too impersonal and cold. George wanted to add an emotional side to it. We had Artoo talking to Ben Kenobi, so we had to be up on a level with Alec Guinness, to come up with a character who was going to make him look good, not silly. We had to achieve a performance through sound, which is not easy, and that is what I struggled with the most.

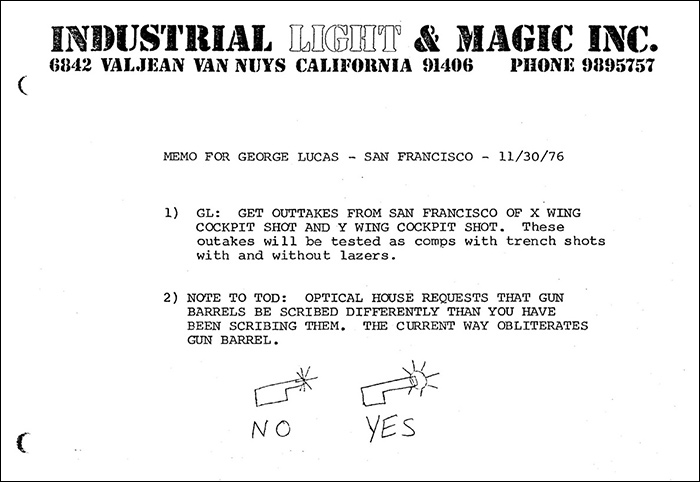

An ILM memo dated November 30 illustrates the correct and incorrect way to animate blasterfire.

Upstairs in the ILM dailies room are: (front row, from left) Jon Berg, Rick Baker, Ken Ralston, Dennis Muren, and Lorne Peterson (in armchair); (second row) Grant McCune, Jibralta Merrill, production assistant Mikki Herman, Penny McCarthy, Gary Jouvenat, and Jim Nelson; (in the back) Dave Jones, Jerry Greenwood, Gary Kurtz, Rose Duignan, and George Lucas.

“George pushed me a great deal on it,” he continues, “and many times I think I stopped too early. I was satisfied with it, and he wasn’t. He would say, ‘No, no, no.’ I’d work for a long time on something I thought was just perfect, and I’d play it for George when he’d come back on Friday—and he’d say, ‘It’s not any good.’ And I’d be upset and resentful, because I had a feeling I was failing. But I was inexperienced. I had never worked with anyone like this before. He’d never be harsh, by any means, he’d just say, ‘No, it’s not what I want.’ As he was in every area, he was meticulous. He wouldn’t let anything slip by without his approval.

“But it worked out great,” Burtt says. “The final approach we took was this: I’d look at a reel, and I’d write down what I thought Artoo would be saying in English, like ‘I’m hungry,’ or ‘Look out, the stormtroopers are coming,’ or ‘Gee, look at that explosion.’ Then I’d show George, and he’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s about right. Try to come up with some phrases for that feeling.’ So I would make up a phrase. We went one phrase at a time in the picture. It started out very slow. It took forever to finish reel one—six weeks, I think. After that, it began to go a little bit faster. Originally, I tried actually making sounds that had the same intonations and inflections as the line in English, but that didn’t work. In the end it became a matter of establishing basic emotional levels: excitement, cute squawks, inquisitive whistles. I’d play his ‘words’ on the synthesizer while I made sounds into the microphone at the same time, and the two would be blended. I’d whistle and coo—a bunch of coos, that’s the sound that George does very well, it’s one of his ideas—I’d sigh and groan, and move the oscillators of the synthesizer. So it was almost always a blend of a human sound with an electronic sound. We got the organic and the electronic combined. Once we had the technique down, I would audition my performance for George.”

“The first effect that Ben Burtt laid in was the exclamation of Artoo when he got hit by that Jawa shot and fell over,” Richard Chew remembers, “and it just broke me up. The film really came to life.”

The adventures of ILM continued in November 1976. Joe Viskocil and Bruce Logan were now helping Richard Edlund do explosions, eventually blowing up seven models in the Van Nuys facility. “We had one really glorious explosion of one of the TIE fighters,” Viskocil says, “and Richard almost lost his ear.”

In the ILM editorial department there was another close call. “I used to take pieces of film I was working on and put them over my neck,” Dykstra says. “Every once in a while, I’d screw up and put one of the pieces of the film that was around my neck into the Moviola—and almost cut my head off!”

Upstairs, in a room with some fairly dilapidated couches, dailies of special effects shots began to be a regular occurrence. The attendees would offer their critiques, but would also begin to scratch themselves after a while (some ILMers were bringing in their flea-ridden dogs, who would sleep on the couches). The critique most often heard was, “Bluespill! Bluespill!” Because the blue of the bluescreen—the part of the shot that was supposed to disappear—could be seen invading, spilling into the miniature or even principal photography.

“I have a feeling that it’s impossible to totally avoid bluespill in this situation,” says Adam Beckett, who ran the rotoscope department. “I’ve heard some grumbling that ‘they weren’t as careful as they could be’ in England, but that would derive from our initial failure to supply the plates. So various excuses on both sides were made.”

“It was a real difficult thing having to learn how to use this new camera equipment, having to start and stop motors, and vary the speeds of motors during the shots to make it look as though ships are actually making believable aerodynamic rolls and banks,” Dennis Muren says. “Some of those shots were absolute killers. I had to come up with a lot of ways to not use the motors, so I could use what I’d learned on space films to give realistic-looking motions.”

“I think John Barry and I conversed a couple of times, but he was so far away,” Dykstra says. “And given how much there was to do, it was simply impossible that problems would not happen on the set that would make the special effects more difficult to do down the line. In the compressed span of time he had to complete all of those sets, he could not be there to make certain there wasn’t a bluespill problem or that there were no yellow lights or whatever.”

Apart from noting the technical shortcomings of what was shot at EMI, the ILM crew was seeing the story of the movie for the first time. “None of us realized exactly what it was about until we saw some footage from England,” says Richard Alexander. “Suddenly, the day we saw the dailies, we came out of there saying, ‘Hey, this might be pretty neat.’ ”

While the make-believe percentages disappeared in November, a new system of tracking took its place, with each shot followed until it was deemed “OKAY G. L.”—approved by Lucas. Though the escape pod shots were completed first, the very first shot “accepted” was the Death Star firing a laser cannon, photographed by Muren. The schedule indicates that two other shots were approved by Lucas on October 16, 1976, but only a few more had met with Lucas’s okay by November. “This whole thing has been pretty strange for me, because I came from a traditional way of doing special effects,” Muren says. “To come in and work with electronics and everything—it’s just something that I’m still getting used to.”

A November 15 memo in the ILM archives indicates that a November 22 meeting was scheduled with the “monster people” so they could review the cantina sequence and prepare for the reshoot, whose funding was still in question. Meeting notes explain how elephants were to be made into banthas: “New tail will be dragged. Should be made of light, furry and durable material. Head piece depends on what elephants will tolerate.” Attendees also discussed whether it would be a good idea, for the safety of everyone, if the elephant trainer might be disguised as a Tusken Raider, so he could remain close to his pachyderm player.

One story that comes to a close around this time concerns ILM and the union. About three-quarters of the way through production a number of “established” industry people developed a renewed interest in what ILM was doing. Word was circulating about some of their more unique approaches to special effects. “It finally came down to a meeting,” Tom Pollock says. “Jerry Smith and Joe Berna came down to the facility, and ILM put on a rather brilliant performance.”

“When the union boys came in to look us over, I had a program in the camera,” Richard Edlund says. “I pushed a button, and the camera went through its gyrations, down the track with no one touching anything, with the lights flashing and the counters buzzing—and stopped right in front of them. They were kinda taken aback because they had never seen anything like this. They knew that we had brought home the bacon. So they said, ‘Okay we’ll take you guys in.’ ”

Two key individuals in the race to complete the film were Edlund and Muren, who were alternately using the main camera, each with his crew, literally night and day. “We split the shots up pretty much however we felt like it, and that worked out pretty well,” Edlund says. “We got along quite well, and there weren’t a lot of egos involved. Everybody knew what the project was and were giving their input because everybody had this common cause.”

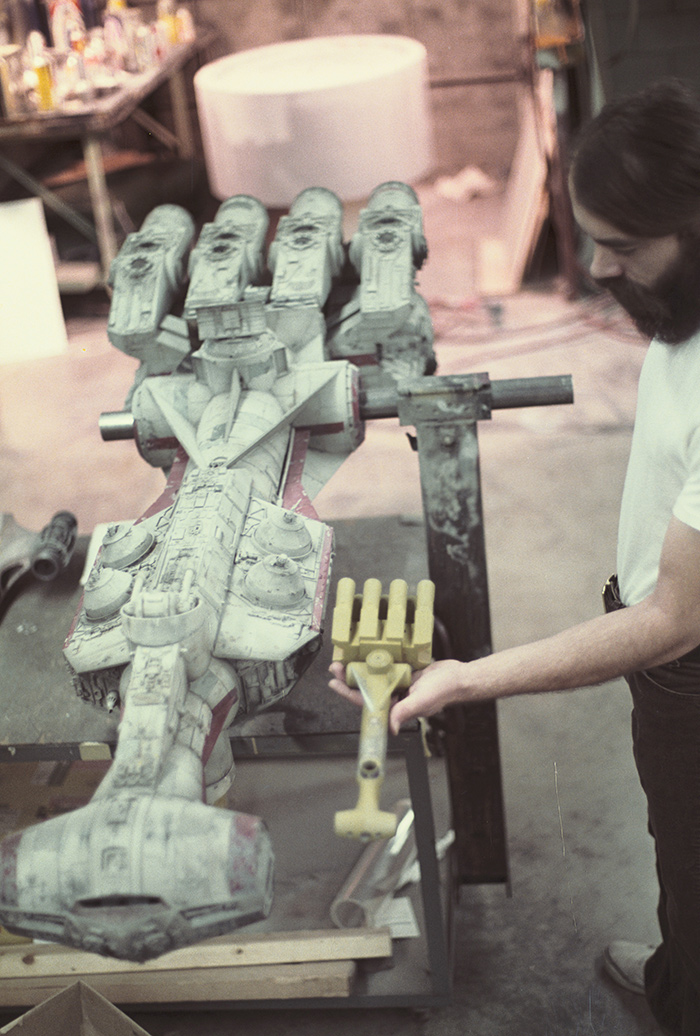

“The Rebel blockade runner was almost the last ship finished,” says Joe Johnston. “On the first pirate ship, there wasn’t really enough detail on it; it didn’t look like it was done by real movie model builders, and the paint job was amateurish. The second version was real nicely done. We’d had the chance to do all those other models in between and then go back to the blockade runner. It really showed what everyone had learned about model building. It was supposed to look like a ship that had been assembled from other ships. George said he wanted something that looked like a fish head, after we’d taken the original cockpit and put it on the Millennium Falcon. I think he finally did me a little sketch of this hammerhead thing, and that’s what it ended up like.”

The ship sits on a table in the model shop with Dave Beasley, David Jones, and Paul Huston working on another ship.

Model builder Lorne Peterson.

The two special effects photographers divided up the work along the following lines (though sometimes a shot would have several parts that would be subdivided):

Richard Edlund: “The opening shot, most of the pirate ship shots, most of the bigger ships I did; and I did the trench itself.” “Richard liked the dogfights,” Muren says, “where there’s one ship pursuing another and two ships racing along the trench. He also shot the training remote.”

Dennis Muren: “The multiple ship shots, like the Y-wings diving down together and going into battle, that’s the stuff that I did. I did most of the shots with the ships flying through the trench, the ship elements, although Richard shot the trench element; and I did all the shots of the ships flying toward and away from the Death Star.” “Dennis did a lot of the X-wing stuff,” Edlund says. “He did the armada scene and the approach to the Death Star, and the peel-off shot.”

As Edlund and Muren appraised certain shots and sequences, they had to always maintain an equilibrium between technology versus artistry versus necessity. They thus made “maps of the galaxy” to show where the sun would be at any time, “but it really worked out best when the shot dictated how it was lit,” Edlund says. While Lucas hadn’t been enthralled by the lighting in earlier shots, the later ones were much improved by his increased communication with Edlund. Muren had his own learning curve. “I was very skeptical of the Dykstraflex at first,” he explains. “It was used for a lot of shots—dogfights and ships moving quickly—that it didn’t need to be used for. I think those elements could’ve been shot at high speed with wires or poles against blue. But everything was set up for this system.”

The more Muren worked within that system, however, the more he came to realize its advantages. In fact, the experimental attempts made at Nine-Ten, using more low-tech approaches to fly ships, ultimately were not compatible with the high level of work that began to come out of ILM. “You’re working in a very slow-motion situation,” Muren says. “And a lot of ideas come just as you are doing the work; you have an idea on how to make something better just as you see it happening. If you were trying to do something with ships on wires and you got an idea to change a motion, it would be a big deal: You’d have ten people who would have to do the work, and they would start grumbling because they don’t want to do it, and the producer would be pacing back and forth. But out here nobody has to know about that but me. I can just reprogram a shot. It takes me only two minutes to change the entire direction of the ship by just running a motor [in the Dykstraflex] to the left instead of to the right. That’s one of the neatest things about it. You can get very spectacular-looking shots done by an individual instead of a group. It’s the neatest tool that’s probably been made to do aerial footage.”

But even with the innovative equipment, the poetry of the flying ships had to be implemented by humans. “What is more interesting is getting into the pantomiming of the ships, the motions of the ships,” Muren says, “which are completely created by Richard and me. That was really difficult! To make these ships look like they’re flying, like they’ve got weight, because you’re creating motion out of nothing.”

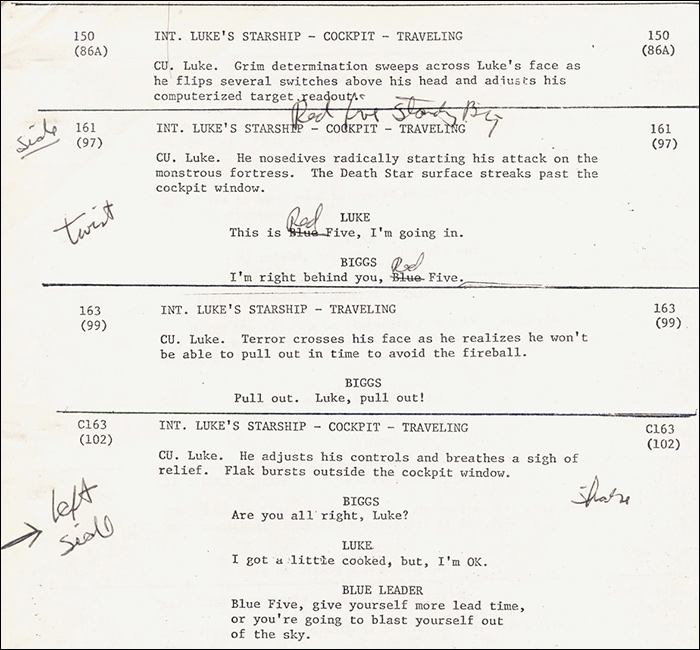

Lucas’s ongoing corrections to the final script make plain the decision to change the “Blue” Rebel pilots to “Red,” though in the final film at least one pilot still wears a helmet with a blue insignia.

Grant McCune looks through a storyboard binder.

“No matter how sophisticated your equipment is, no matter how neat it all is,” Edlund adds, “whenever you get into production, you invariably wind up making do with what’s at hand. You’ve got a little bit of light flare coming from sunlight, so you tear off a piece of cardboard and tape it on—and it looks quite amazing and that’s real professionalism.”

Following the first cut, there was a new temp cut every couple of weeks, which only the same small group would review. After the first major structural changes, other adjustments were made to the successive cuts: for example, to the opening shootout. “There were two shots of actual humans getting hit, with big explosions on their chests,” Lucas says. “But I cut those out after I saw it; it was a little too extreme. I did have big blasts on the stormtroopers, but I avoided them on humans.”

The scene in Obi-Wan’s house was rethought, too. As originally scripted and shot, Luke and Ben watched the hologram, discussed the Force, and then decided to save the Princess—which, upon viewing, seemed a bit heartless because of the lag between her plea for help and their decision to fly to her rescue. The scene was re-edited to start as if they’d already begun talking about the Force—then, as soon as they see the hologram, Ben decides to travel to Alderaan. To smooth over the edit, a brief shot of R2-D2 beeping impatiently to play them the hologram was inserted, culled from other footage of the robot.

In the hangar, lines were shortened and dialogue about Luke’s father being a great pilot was cut. But it was the end battle, by far the most complicated part of the story, that required the most editing work. One of the first changes was to clarify the number and characters of the supporting pilots, some of whom were cut. “That decision was really made in terms of what would be easily identifiable,” Lucas says. “We had a Blue crew but we couldn’t use blue because of the bluescreen [parts of their ships would’ve disappeared]. So we were left with Gold Leader and Red Leader.”

The end battle was also running too long, so Luke’s two trench runs were combined into one. This created tighter storytelling, but also several editorial challenges. Within one trench run, the following would now have to be conveyed either visually or verbally: Luke’s initial intention to use the computer, Ben’s dialogue, Vader’s actions, R2-D2’s drama, Han’s arrival, the fate of the other pilots, Leia’s feelings—all within the believable length of physical space along the trench. To draw out the suspense, Lucas had decided to shoot second-unit footage at ILM of the Death Star preparing to fire, some of which would be added to this sequence, along with coverage taken of Peter Cushing, stolen from an earlier scene that had been shortened. “It was all editorially manufactured,” says Marcia Lucas, who, just after Thanksgiving, left the picture to help Martin Scorsese on New York, New York.

Just before Christmas, another cut was ready. “For the second screening we hadn’t tried to keep Ben’s tracks in sync,” Hirsch explains, “so we looked at the picture with just the work track. There were no sound effects, and everyone thought it was a disastrous screening except me. I believe it’s good to look at something with no sound effects and no music, because they can mask your understanding of what’s happening editorially.”

From that point on, however, Burtt’s sound effects work more consistently dovetailed with what was being done in editorial. As soon as they finished a reel, he would mix in the sound and give it back to them so they could hear as well as see how it played—an unorthodox but effective methodology. Usually, sound work would have come as the last step before the film’s release, with someone given a final cut of the film and asked to simply fill in the sound holes.

“The editor would cut a reel and a week later he’d see the mixed version of it,” Burtt explains. “I would add all the sounds—lasers, spaceships, Jawas, Sand People. The editors would eventually work with nothing but mixed tracks. In fact, they began to depend more on the fact that Artoo could talk and they would cut to him much more often—because they knew he could talk. They would say, ‘Why don’t we bounce to Artoo and get a reaction?’ That would not have happened had they not known they could get the sound in. So it was a really unique experience in that respect.”

“As Ben evolved the Jawa language, it integrated so well,” Chew says. “Each cut that we saw not only showed us the effects of structural and dramatic changes, but we also heard the evolution of what new things Ben and George had come up with.”

To create the Jawa language Burtt had studied several African dialects; next he recorded other employees at Park Way speaking and yelling the words, which were then sped up or altered before being mixed into the film. “They cut the Jawa sequence originally with just the cute guys running in and picking Artoo up,” Burtt says. “And then I took that reel and added the Jawa voices. When we showed it, one of the editors was just rolling on the floor laughing. The Jawas talking made so much difference, because it created a feeling that there were little beings in those costumes.”

Some time before Marcia left, the editors also started building a temporary music track. “Dvorak’s The Planets was used at the beginning,” Chew says. “And Liszt preludes over the breaking into the jail sequence. George was having a lot of fun. He would bring in a record whenever he got back from LA. He would have a new idea for the temp track, which was the best way for him to convey to Johnny Williams what he wanted. But I didn’t know which way he wanted to go with the music at first. The first time we talked about it was when I was editing that cantina sequence, so I said to him, ‘Hey, George, have you ever heard Tibetan music, because I think the chanting and the animal-bone instruments might really be appropriate.’ And he said, ‘No, I’m going to use Benny Goodman.’ And I went, ‘What?!’ And he said, ‘Yeah, they’re gonna play swing, man!’ ”

In addition to overseeing the film’s special effects, editing, and sound effects, Lucas was also very much involved in its marketing. Charles Lippincott had been trying to energize the burgeoning science-fiction and comic-book convention circuit, and word of mouth was beginning. The novelization had just been published, and a Marvel comic-book adaptation was well under way—but one of the biggest draws to any “coming soon” film is its trailer. Plans for the preview had begun in the fall of 1976 and crystallized in November. But the reality, given the few special effects completed, was that the best production could hope for was a short, powerful burst that would alert audiences to the upcoming movie.

Presumably because the pressure was so great to tightly control costs, assistant optical editor Bruce Green kept a day-by-day itinerary of his time and travel while he acted as go-between on last-minute adjustments to the trailer, uniting its disparate elements and troubleshooting. The following is his (abridged) saga:

Ben Burtt in his basement editing suite at Park Way.

Ben Burtt petting Indiana, Lucas’s dog and inspiration for Chewbacca.

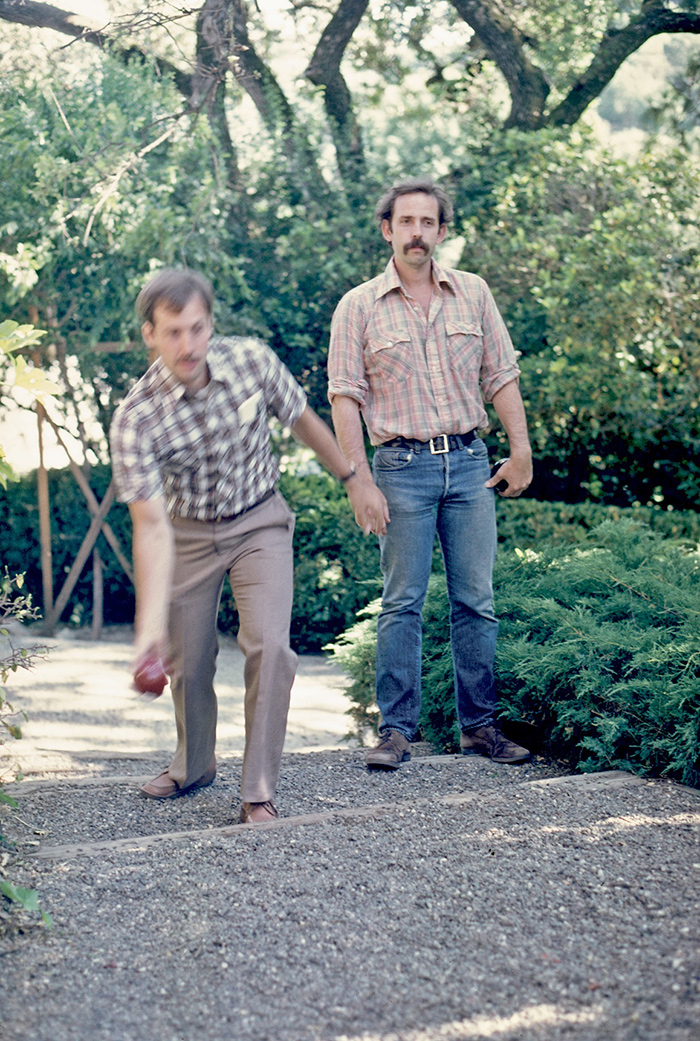

Ben Burtt playing bocce ball with Walter Murch.

“November 26: I drove to the editor’s cutting room in Hollywood and met with him, Gary Kurtz, Charlie Lippincott, Adam Beckett, and three people from the ad agency. We discussed the storyboard, the animation and opticals, the time factor, and other related materials. (3 hrs.)

November 29: We saw the rough cut [same place and people, minus Beckett] of the trailer and discussed what shot could not be used because of problems with the effects. We talked about the music. (3 hrs., 18 min.)

November 30: Phone calls to editor and optical to coordinate effects for trailer. (2 hrs.)

December 1: Editors meeting; prepared fx budget. (3 hrs., 18 min.)

December 2: I drove to Tech 20 to pick up negative; talked with negative cutter about problems he was having finding certain scenes and his stolen dog, and how to find that, too. (1 hr., 13 min.) Bring neg to MFE [Modern Film Effects] and explain to lineup person the order to assemble the IPs and the time element. (2 hrs., 7 min)

December 6: Drove to ILM to view trailer work for any possible last-minute changes. (37 min.)

December 7: Drove to MFE to discover a matte for the exploding title had not been made. Had animator reshoot matte and had this developed at MFE and cut in. Made last check at optical house of all elements and went over all effects with the printer operator before actual printing began. (6 hrs.)

December 9: Viewed first answer print at 8 AM at Deluxe and made timing changes. Cut in reshot scene. At 1 PM viewed second answer print—authorized striking of 10 prints from original negative and making one CRI; drove back to ILM to be told agency wanted to adjust explosion at end of trailer. Went to MFE, recut last scene and authorized reshoot of this scene. (8 hrs.)

December 10: Viewed reshot scene at MFE and cut into trailer at Deluxe. (6 hrs., 4 min.)”

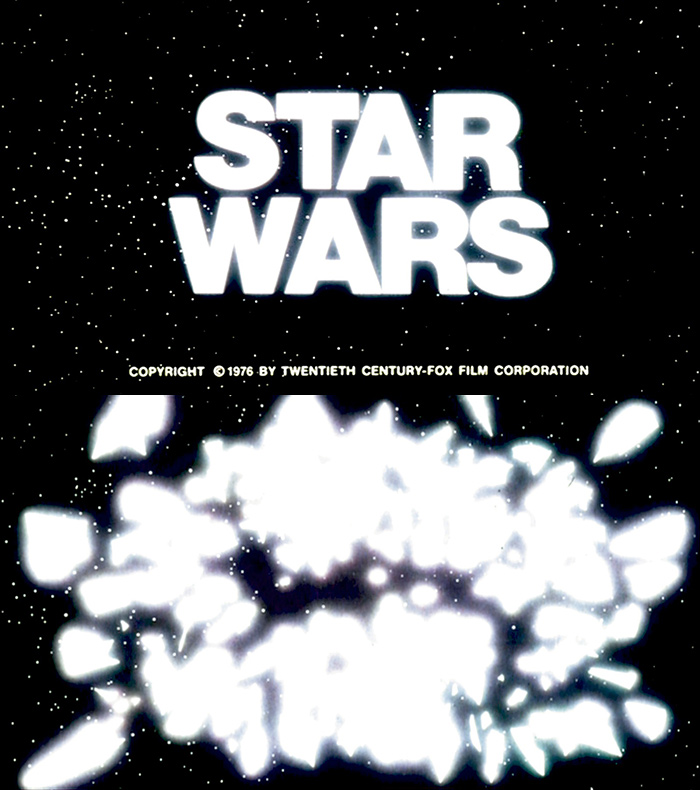

The budget for the trailer, compiled on December 2, for 107 seconds (160 feet of film) was $3,915.10, of which $1,268 was spent on MFE’s opticals. The special effect of the exploding Star Wars logo was created by Joe Viskocil and Bruce Logan. Ironically, the shot in the trailer of Leia and Chewbacca in the pirate ship cockpit was a front projection one; the other special effects consisted of a few finished shots from the gunport battle.

“The trailer was more about the spirit of the film; it introduced a lot of different characters,” Ken Ralston says. “One thing they did have was a couple of the very early lightsabers.”

After Lucas approved the final trailer, problems arose with Fox—whose collective anxiety concerning the film was not being mollified by its progress.

“There was a lot of the tension building up at the time,” Ladd says. “People were saying, ‘Change the title’ and that we couldn’t go with this trailer. I told them to show the research to everyone and to discuss the title change, but that I couldn’t think of a better one. It was a case where all the research strikes were against the film. The board of directors did see the trailer themselves at their meeting in December, and, although they didn’t like it, they didn’t make a big issue of it. But one of the board of directors disliked the title very much.”

Apparently the title conjured up, for some, images of Hollywood starlets at war. “My way of handling it was to say, ‘If you want to change the title, come up with more titles and we’ll see if we like them,’ ” Lucas says. “We essentially put the problem in their half of the court. I realized they probably wouldn’t be able to do it, and they didn’t, so we let it go at that.”

Nevertheless, the issue of title and trailer persisted even after the trailer was released in time for Christmas. Saddled with what sounds like part of Antonio Vivaldi’s “Winter” from his Four Seasons, the slow, ominous classical music was at cross purposes with the trailer’s upbeat visuals, making it play like a schizophrenic excerpt from 2001 and helping to create a divided reception. “It was obviously drawing certain people in through curiosity,” Ladd says. “I saw it play here at the Avco where it wasn’t very well received, and I saw it in Tucson where it was badly received. There was also all kinds of new market research saying that the picture will absolutely not work if we call it Star Wars and if we keep the trailer on—and that the picture really had no chance. But we kept saying, ‘We’ve got to have something.’ I mean it had to have a chance just to at least get its money back!”

Producer Gary Kurtz and George Lucas look through enlarged photos for possible marketing material.

The teaser poster.

Frames from the trailer for Star Wars—including one of the two or three front projection shots in the film, “very early” lightsabers, and the exploding logo.