The work ethic at Park Way gave way to the occasional break. Howard Hammerman, who started in June 1976 as the general repairman, remembers: “Everybody in the whole company could come and sit at one table and have Christmas dinner. All the people that worked there and their families and kids, we all came to the Park Way house and sat and talked about movies and harassed George and teased him about why is there sound in outer space. I questioned him about that at the first Christmas dinner, and he looked at me and said, ‘I’ll tell you what. We’re going to put a little platform out there floating in space [laughs] with an orchestra on it so that it’ll make sense.’ ”

In January 1977, with editorial well in hand, the director decided that only Paul Hirsch needed to stay on. “I went up to San Anselmo and was originally supposed to stay until the end of the year,” Hirsch says. “But George asked me to stay until the end of the picture, which I wanted to do because I loved the picture and I loved working for George.”

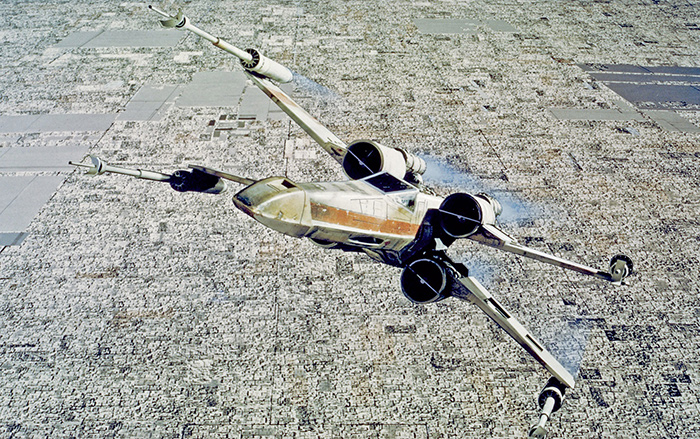

Farther south, while Ladd pondered a bleak future for the overbudget and late film, ILM kept making steady progress. They had begun working on the escape from the Death Star sequence on September 29, 1976, after Joe Johnston had painstakingly reboarded the sequence; by late January 1977 Lucas had approved most of the shots. While things were not always well between the director and the head of the special effects crew, on the whole Lucas’s estimation of ILM was continuing to grow—and their situation had vastly improved when Luke’s two trench runs had been combined into one.

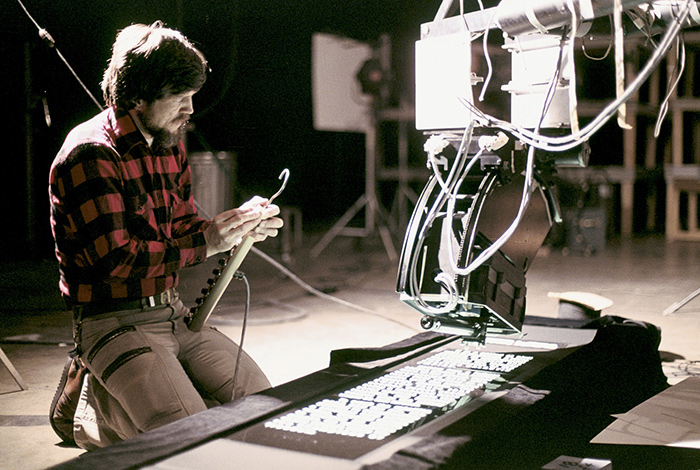

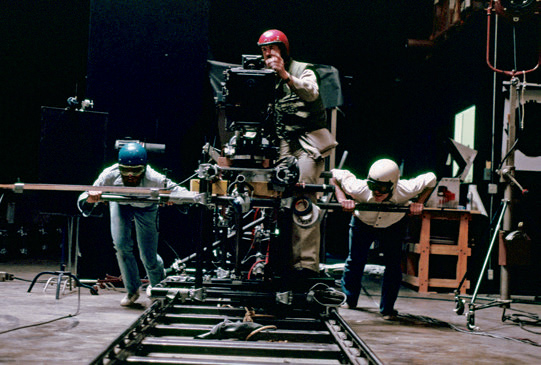

“I had heard that all of a sudden things were much easier, because we didn’t have this entire run to do,” Dennis Muren says. “I was still working independently at night with my crew, with Ken Ralston, who was my assistant; and Richard was working with Doug Smith in the daytime. And as it went on, George would give me a rough storyboard representing one frame of what he wanted and would say, ‘I’d like it to go from here to there, and make it run about 86 frames.’ We’d discuss if he wanted to use a telephoto or wide-angle lens, but after a while he came to trust us pretty much.”

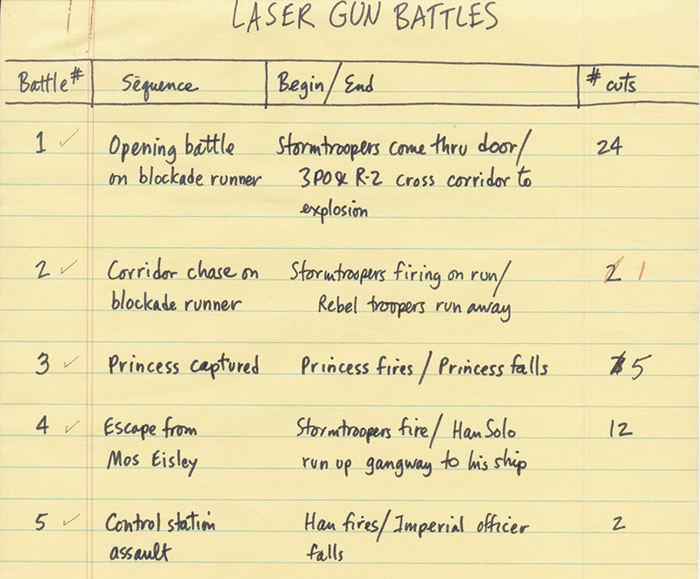

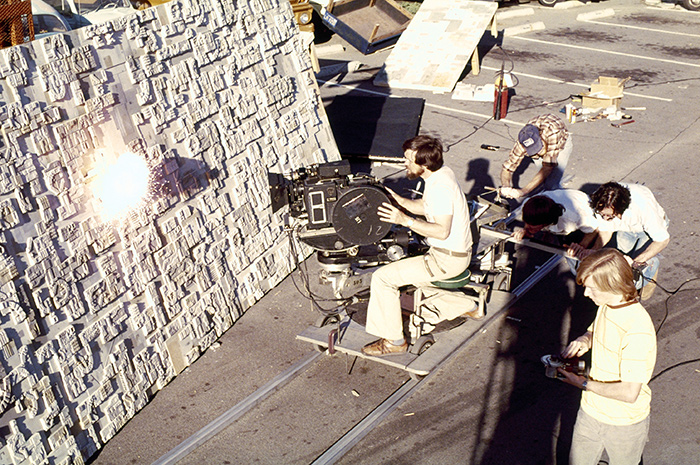

Van Der Veer Photo Effects was given written instructions on how to do the laser gun battle animations, which included the number of cuts, bolt directions, and so on.

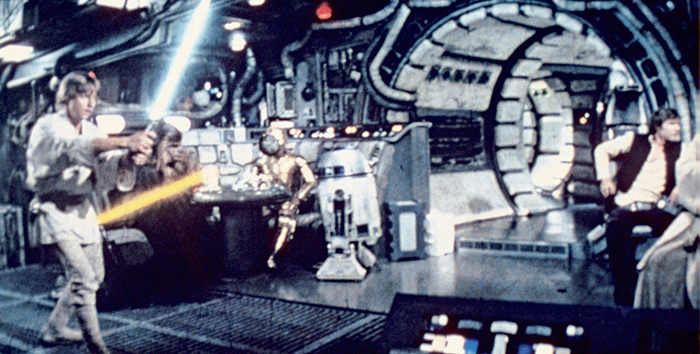

The effects house worked on the lightsabers as well.

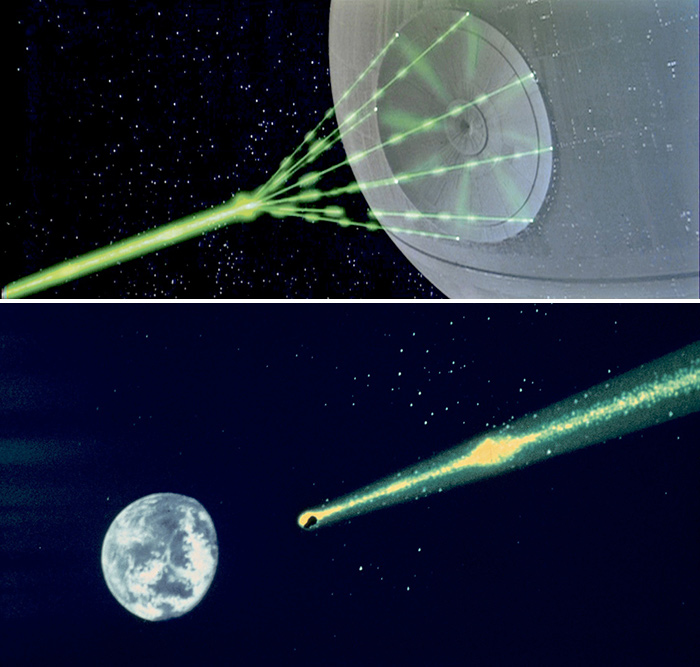

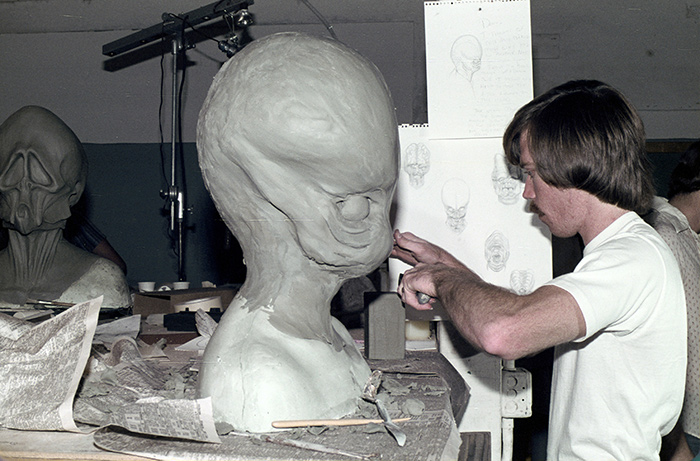

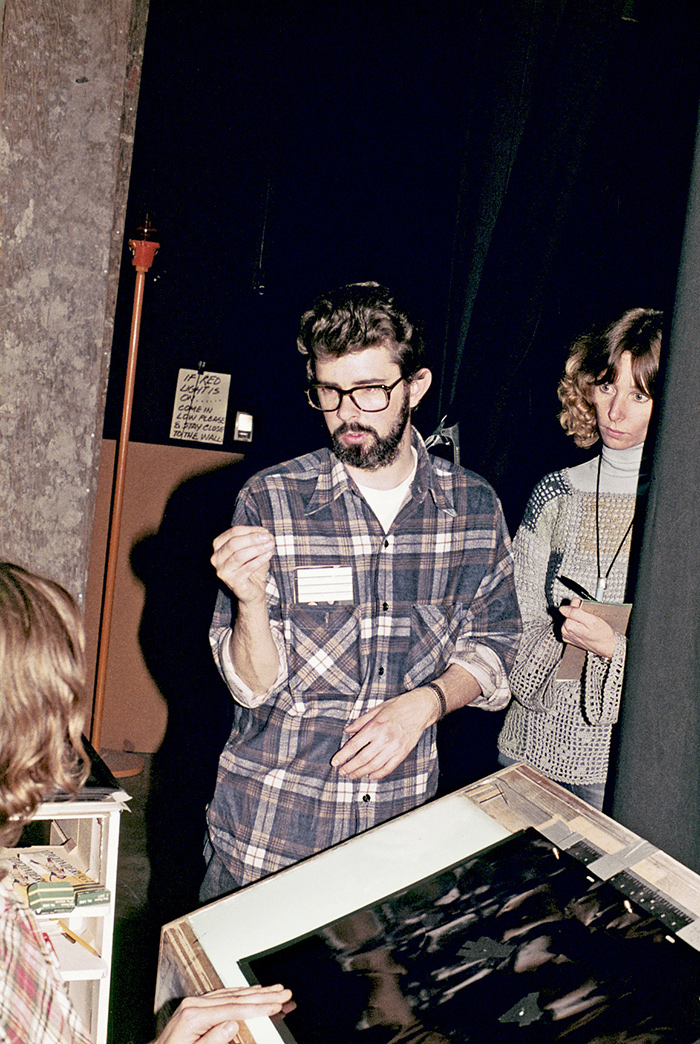

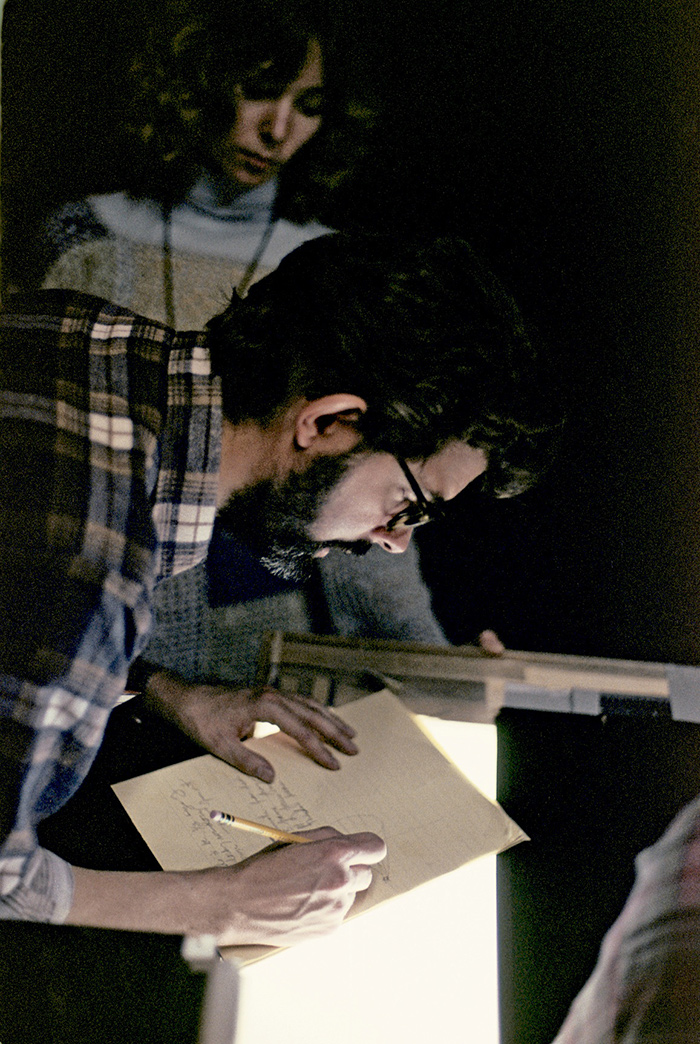

ILM’s animation department took care of the Death Star blast and vetted all outside work (below, animator Pete Kuran, production staffer Rose Duignan, Lucas, and animation supervisor Adam Beckett study laser sword possibilities).

“We figured that once all the personnel were trained and everything was moving,” Robbie Blalack calculates, “that we could do a medium-difficulty shot in about two and one-half weeks.”

Upstairs in Film Control, Mary Lind and her group were reaching peak activity. “There were five editorial benches,” she says, of the increasingly crowded work space. “When I first put the shelves up, everyone was saying, ‘You’ll never fill them.’ I filled them and emptied them three times. When George, Gary, and John would all come up to the room and have a discussion, you literally had to raise your arms in the air to walk by, so we finally knocked out the wall between us and Joe Johnston’s art department, because you couldn’t even breathe anymore.”

Before showing a cut of the film to John Williams, Lucas and Hirsch added to the temp track. The director had designed his film as a “silent movie,” told primarily through its visuals and music, so great care was taken to obtain the right moods. “We used some Stravinsky, the flip side of The Rite of Spring,” Hirsch remembers. “George said nobody ever uses that side of the record, so we used it for Threepio walking around in the desert. The Jawa music was from the same Stravinsky piece. We used music from Ivanhoe by Rózsa for the main title. George was talking about having a majority of the film set to music.”

“George had listened to a lot of records and done a lot of research, and people had given him records,” Burtt says. “He had picked out some material from Dvoˇrák’s New World Symphony for the end sequence of the great hall and the awards. He had chosen some of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony for Luke’s theme. We slowly built up temporary music tracks and mixed them in with the film, so we had a temporary version of the film with an essentially complete sound effects track and a patchwork music track that highlighted various moments in the picture. At this point Johnny Williams was brought in.”

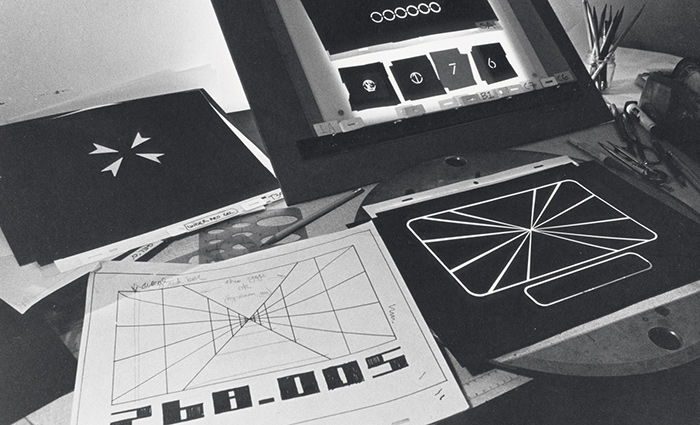

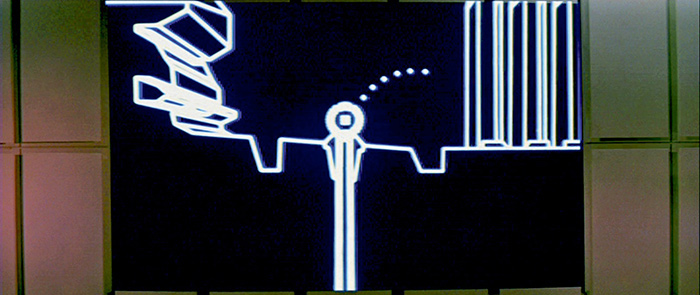

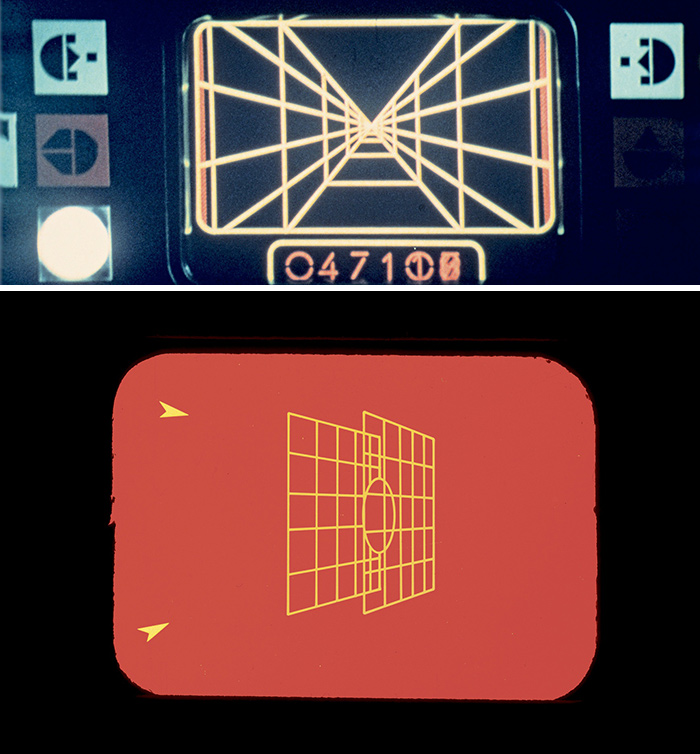

On December 14, 1976, graphics display artist Dan O’Bannon delivered a status report to Gary Kirtz listing his shots. On the “gunport targeting device,” work was finished (by Jay Teitzell).

The “bomb down shaft” in the Massassi briefing room was also completed (by John Wash).

The “schematic wall screen (tractor beam)” had finalized artwork and would be on camera “this week.”

The “rebel targeter” also had finished artwork and awaited camerawork.

The only unfinished artwork was the “Death Star wall screen (approach to Yavin 4)”—“considered by all to be the most important of the series,” O’Bannon writes. “I have withheld this shot until computer animators Wash & Teitzell had finished their individual responsibilities and could work on it together. Imperial technology should appear more advanced.” This graphic would eventually involve Teitzell, Wash, O’Bannon, and Image West.

The graphic showing the approach of the Death Star was “produced” by John Wash.

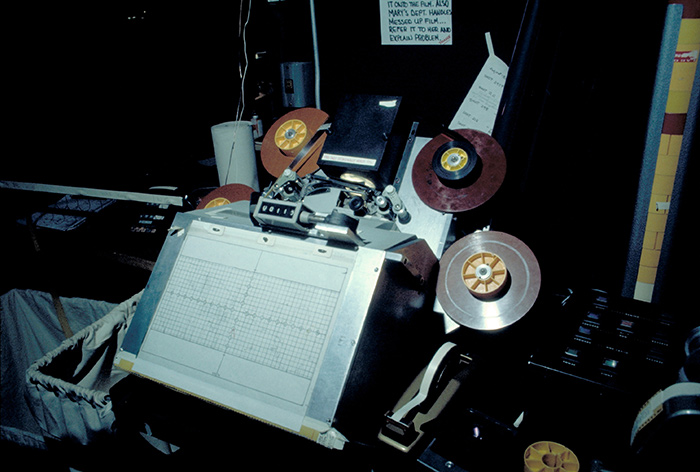

At ILM, its VistaVision Moviola, made from a cannibalized movement (interior mechanism) extracted from a Technirama VistaVision camera.

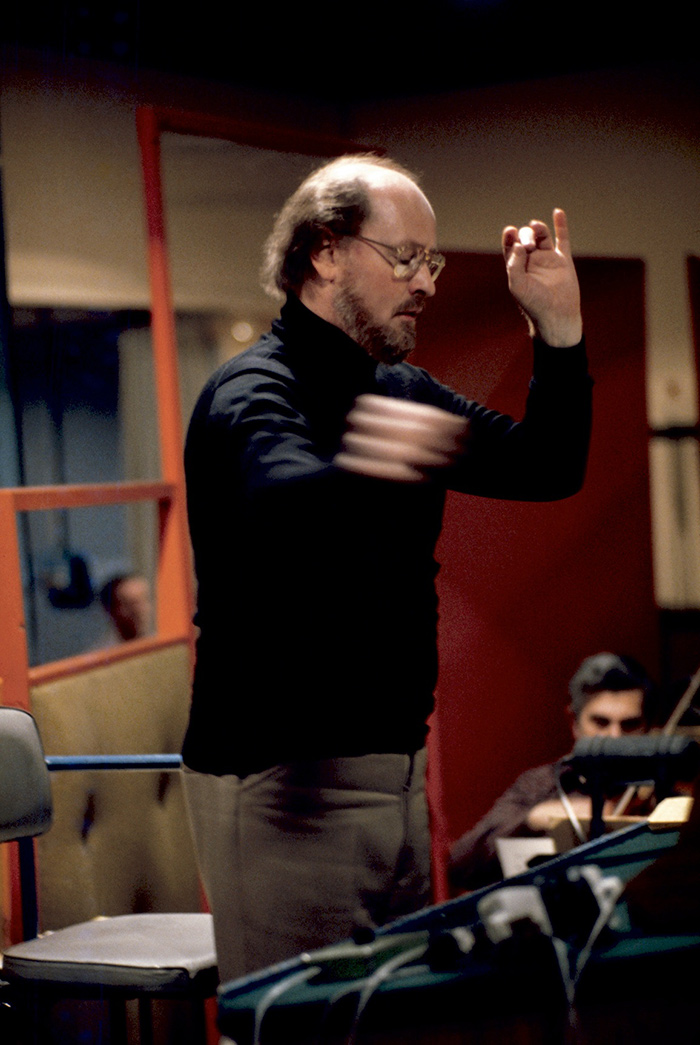

Williams and Lucas

“I started with George just after New Year’s,” Williams says. “I went up to Park Way and he showed me the film.”

Lucas, Williams, music supervisor Lionel Newman, music editor Ken Wannberg, and Hirsch gathered together and rapidly spotted the cues; that is, they decided where the music should go and what kind of music it should be, using the temp track or “source music” as a guide.

“We sat and went over the film reel by reel, over the course of two days,” Hirsch says. “The way it developed, there was a lot of music in the first three-quarters of the film. The idea, though it was never explicitly stated, was to open up some space so the music that came in at the very end would have an even greater impact. So after the gunport sequence, there was no music for a long time, which was contrary to the pace of music that we’d established in the first part of the film. You have to go slow in order to go fast.”

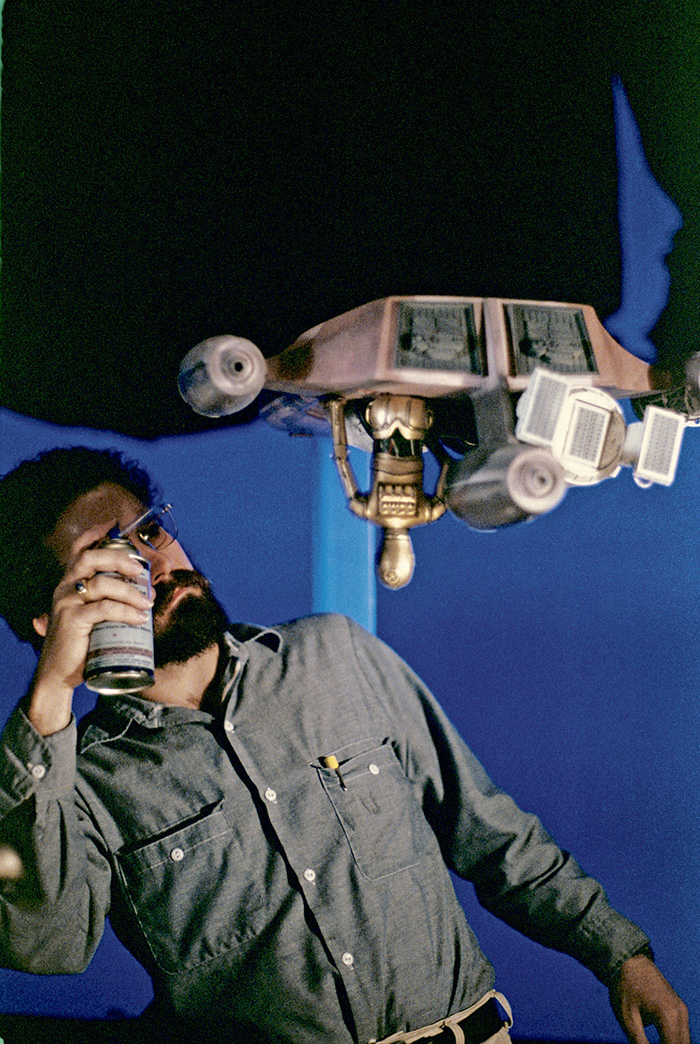

The large-scale and miniature landspeeders were needed for additional shots (with Bill Shourt at the wheel; David Jones spray-paints the miniature).

“What the source music did was convince me that George was right about the idiom of the music in the picture,” John Williams says. “He didn’t want, for example, electronic music, he didn’t want futuristic cliché, outer space noises. He felt that since the picture was so highly different in all of its physical orientations—with the different creatures, places unseen, sights unseen, and noises unheard—that the music should be on fairly familiar emotional ground. I think what George’s temp track did was to prove that the disparity of styles was the right thing for this picture.

“So I came back to my little room and started working on themes,” he adds. “I spent the months of January and February writing the score.”

Even before the new year, veteran sound editor Sam Shaw had also started on the film, with the greater part of his crew joining him mid-January 1977. Shaw had worked on American Graffiti, Cabaret, and The Candidate, among many others. “Ben Burtt worked on the film creating sounds for a couple of years,” Lucas says, “and then when we got down to the final crunch, we brought in a regular sound effects editor from Hollywood to cut the sound effects and do all the other sound effects that had to be done. Ben did mainly the special intricate things that had to be created.”

With understandable trepidation, Burtt handed over his sound library so that Shaw could build the final tracks. “I was uneasy about that,” he says. “I didn’t like the idea of someone else making a lot of creative choices as to where you put it and how you put it in, and so on. I was worried. I asked George if we could do it ourselves. But he and Gary said, ‘No, we don’t have time; we’ve got to have these sound effects editors do it.’ ”

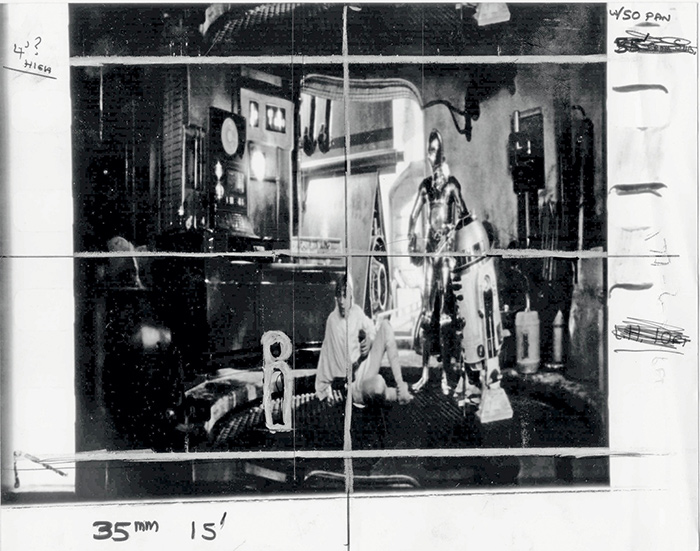

Shaw’s first task was to create the sounds for the motors in C-3PO and R2-D2. “That was a huge job,” Burtt says. “I had never gotten to that on my list; we hadn’t established that as a priority.”

“Everything was a problem on Star Wars,” Sam Shaw says. “The biggest problem was the time, together with the fact that it was very demanding. There is more sound in that one picture than there is in ten average pictures put together. There were over a hundred effect units for each sound reel, so over twelve hundred reels. Everything was just very special; everything you did was something that you hadn’t done before. You never got bored!”

Toward the end of January, Lucas felt ready to screen a cut for Alan Ladd. “It was the first time I showed it to an outside group,” Lucas says. “We did a mix for Johnny Williams with the temp track, and right after that we showed it to Laddie, his wife, Gareth Wigan, and Jay Kanter. A very small group.”

Wigan and Kanter constituted with Ladd a power triumvirate at Fox that had been shepherding their films through the studio labyrinth. After they and Fox executive Leonard Kroll, who also attended, settled into the seats of the screening room constructed behind Park Way, and as the film neared its finale, Lucas noticed that one of the execs was becoming emotional. “I was sitting right next to Gareth, and he turned to me and he had tears in his eyes,” Lucas says. “I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe Gareth Wigan was crying—I thought he was crying because he was thinking, Oh my God—our whole careers are destroyed. Our lives are destroyed! But he said, ‘This is the greatest film I’ve ever seen.’ And I thought, No way! I’d never had a studio executive say that at the end of a screening. I thought, This is really weird.”

It must have been all the more surreal when Lucas remembered the previous reactions of Warner Bros. and Universal to his first two features. Wigan was so moved that upon returning home, “I sat my family ’round the kitchen table and I said, ‘The most extraordinary day of my life has just taken place. I want you to remember this day because I never thought I would have a day’s experience like the day I’ve had today in seeing this film.’ ”

The others had varying opinions. “Laddie didn’t know what to think,” Lucas says. “His wife loved the movie. She was going on, but Laddie was quiet and said, ‘Gee, George, you did a really good job.’ After they all left, Paul and I looked at each other, shrugged our shoulders, and said, ‘What was that all about? It could’ve been worse!’ ”

Around this time, Hal Barwood’s estimation of the film also changed. “I got invited up to a screening that George was having,” he says, “in a little screening room, with William Morris fabrics on the wall and these big easy chairs you could sit in. I brought my two kids, who were about ten, and we sat down and we watched this thing. It was just all sorts of slugs and leader with Magic Marker marks—but I was just knocked silly by the movie. I was just thrilled to the core by this fantastic film. I couldn’t believe it. Of course, I’d been set up to be stunned because of my doubts previously.”

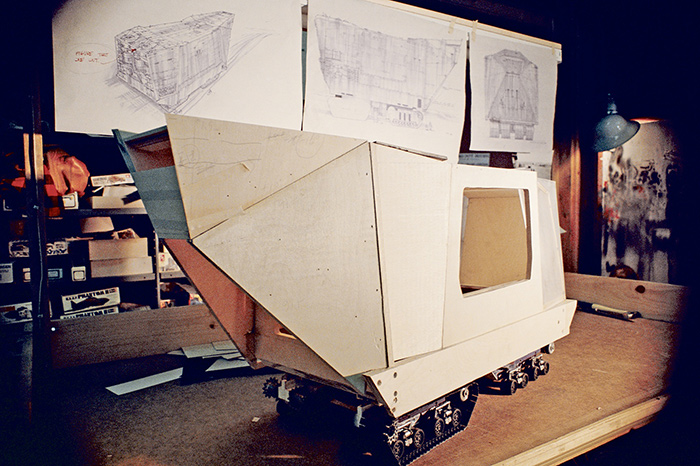

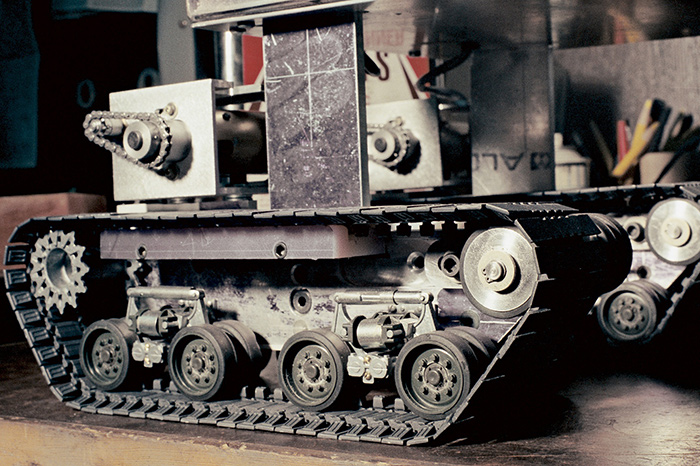

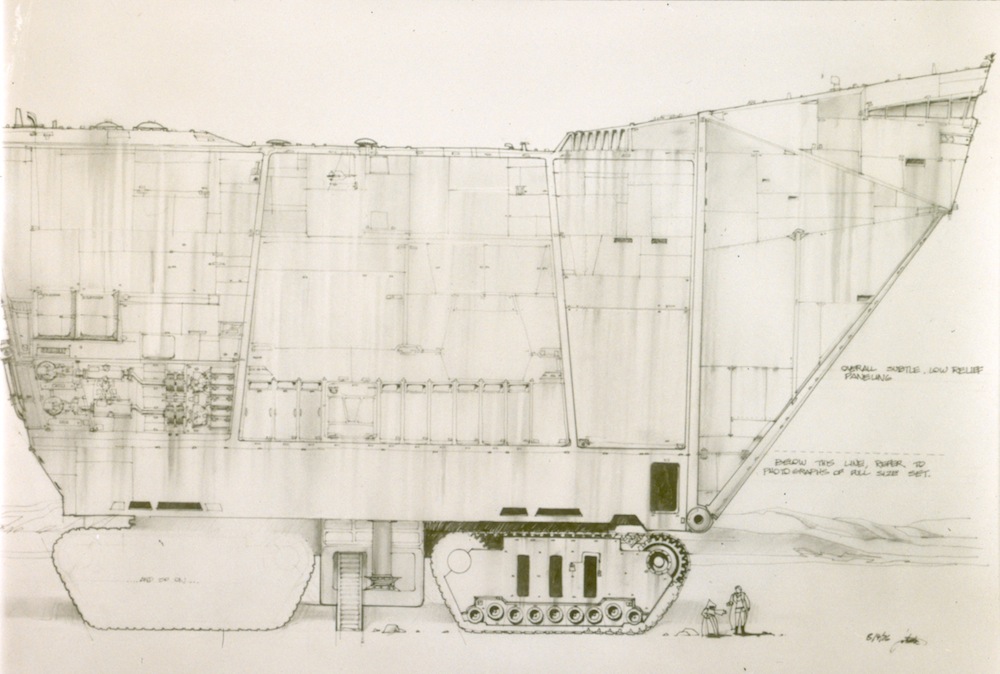

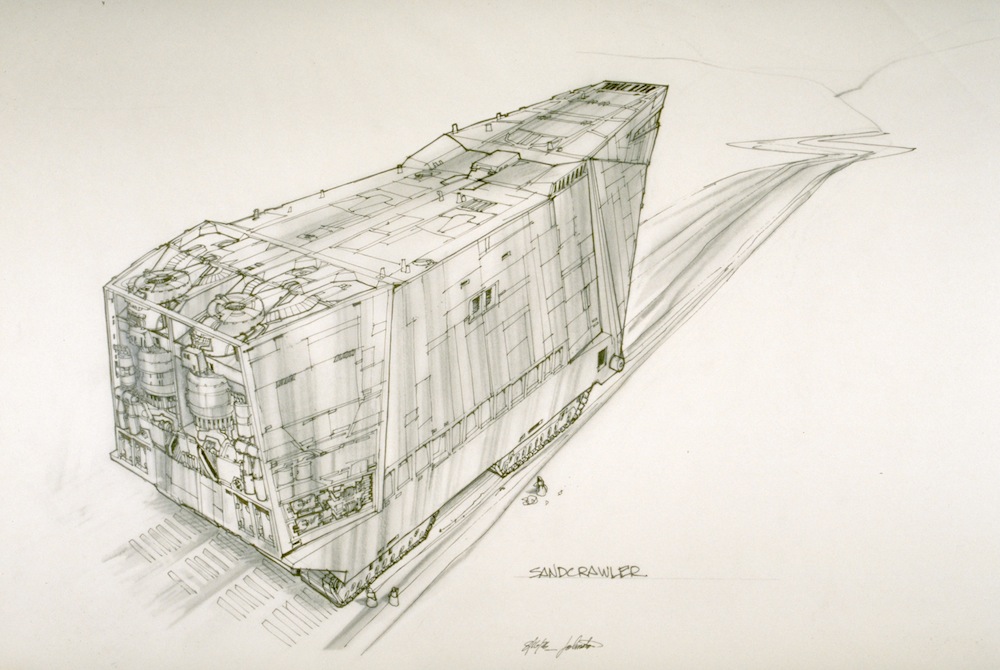

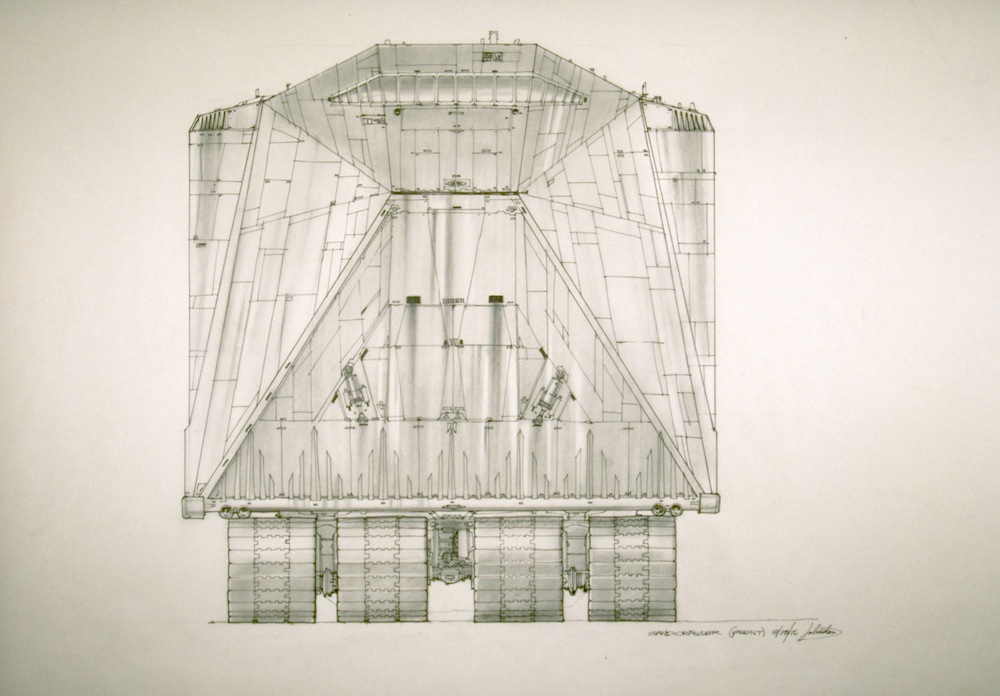

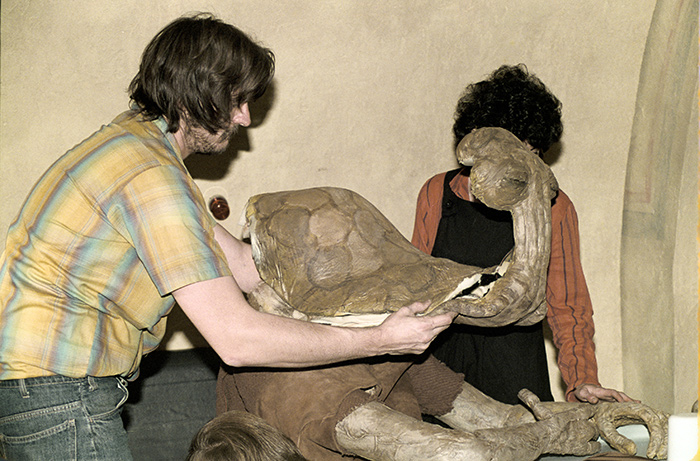

The sandcrawler model’s proportions were worked out retroactively to fit the bottom third that production had built in England. ILM used as a point of reference a shot of the sandcrawler on a hill where its “headlights” could be seen, matching that to the miniature’s. Its mechanics were designed by Jamie Shourt, who installed an electrical system that supplied voltage to the treads based solely on how much was needed, so there would be no spinning wheels.

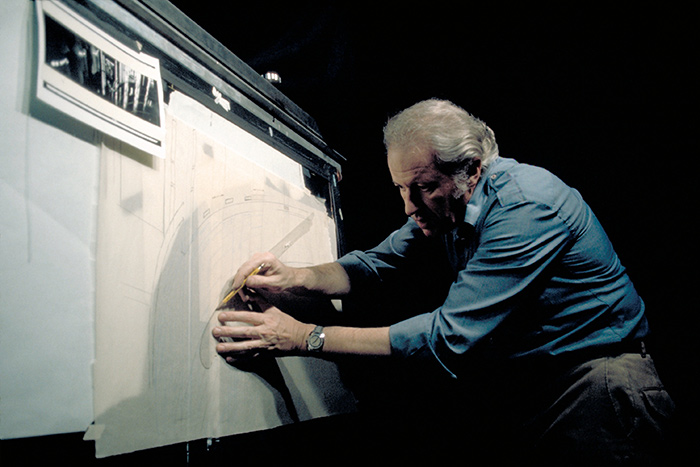

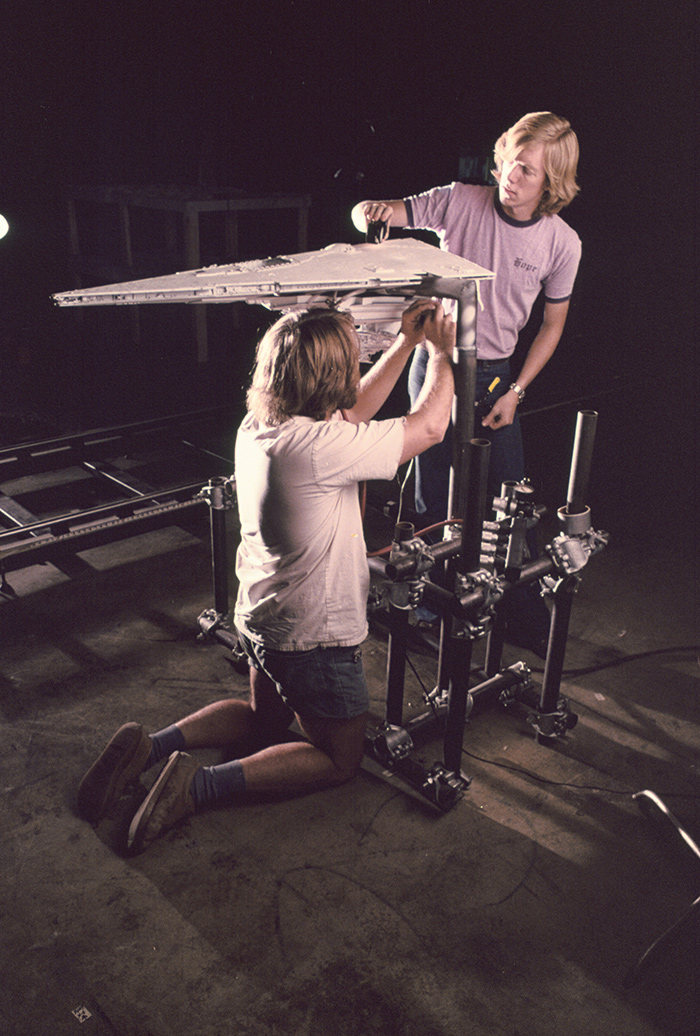

Paul Huston and Joe Johnston work on the sandcrawler model, as based on Johnston’s sketches done in August 1976.

Johnston’s sketches done in August 1976.

Although the reactions of Barwood and Wigan were similar to Richard Chew’s, the businesspeople who would have a large impact on the success of the film—the theater owners—had no idea what the film was like, and they were proving hard to educate. Their lack of financial enthusiasm was causing anxiety throughout the studio, because Star Wars was backed solely by Fox, whereas its two most recent big-budget films—Lucky Lady and Hello, Dolly—had been co-financed with another studio, and hence less risky.

“Lucky Lady had star names and theater guarantees,” Ladd explains, “so even though it didn’t do what everybody had hoped, the cash loss on the picture wasn’t going to be worrisome. With Star Wars nobody was able to get the guarantees. It was a very negative response. One of the key things with a film is getting the appropriate ‘house’ [movie theater in which to open]. So we had to go out early to get the proper houses, and we got absolutely no response at all. Exhibitors were going heavily into A Bridge Too Far, Exorcist II, Sorcerer, and The Deep. So we had great problems getting guarantees for Star Wars.”

Fox had actually started the process back in October, without a print of the film to show, by sending out bid forms to every theater owner throughout the United States. Almost schizophrenically, the form listed the conditions for the rental—an exclusive 12-week run and a 90/10 profit split—which were strangely exorbitant given the studio’s precarious confidence in Star Wars, and which had the effect of scaring off most exhibitors.

During that first month of the year, with the film close to being locked, Lippincott interviewed the three principals, who were also in the dark as to its future. On January 4 Carrie Fisher said, “The great thing about Star Wars is that when I see it, I’m going to be as surprised as anyone, because I’ve not seen any of the effects. Are they going to have my planet blown up? I’m very curious to see what my planet looks like blowing up, what I look like flying through space.”

On January 5 Mark Hamill said, “I would do anything for George. I’d go paint his house. Seriously. But I may never get to work with him again … He told me once that he didn’t want to make features anymore, that he wanted to go back and make student movies. I’ll do those, too.”

“I don’t know what it is going to look like, not at all. No idea,” Harrison Ford said on January 20. “When I was filming, I had no idea how they were going to do some of the things that were in there. It was a mystery. And still is to this day.”

From mid-January to early February 1977 second and third units were scheduled to do pickups and reshoots. Nearly all the shots were going to be on location, with the only set a reconstitution of the cantina alcove.

“The other big argument with Fox was over the cantina set and the Death Valley pickups,” Kurtz says. “In a production meeting at the studio someone said the cantina set was going to cost us $100,000, so the studio said no. They wouldn’t authorize the expenditure. We were talking about fifteen or twenty creatures—the elephant suit would cost $25,000—so I really had to go to Laddie, go down to the studio, and tell them that we estimated that it was going to cost from $30,000 to $40,000, certainly under $50,000, and that it was extremely important for that sequence to be right.

“This was also at the time where they were arguing over paying the Huycks,” he adds. “They wanted $15,000 for their dialogue polish. Fox wasn’t going to pay it. They insisted that George pay for it out of his writing fees. That’s why we were so pissed at the studio. They made no effort to help in any of these areas at all; it would’ve been a goodwill gesture, more than anything else.”

The funds for the cantina reshoot were necessary in part to pay Rick Baker and his small crew, who had been engaged to make the cantina creatures. “A good animator friend of mine was friends with Dennis Muren,” Baker says. “He heard that they were looking for people to do these aliens, so he gave them my name.” Baker had started doing puppets and makeup for low-budget films like The Thing with Two Heads (1972) but had recently graduated to big-budget films with the remake of King Kong (1976).

“George explained that there was a scene in the film where there is a bar and there are a whole bunch of aliens in it,” Baker adds, “and he just wanted some more aliens. George and I talked for a great deal of time and we were both very excited about what we were talking about, I think, and maybe that’s why he went with me.” Baker’s bid was accepted, with the caveat that only Stuart Freeborn would get a credit on the film, as he was the primary artist. Baker agreed and started his team, which consisted of Jon Berg, Phil Tippett, Laine Liska, and Doug Beswick.

While they began sketching out alien concepts, Kurtz’s negotiations with Fox netted them $20,000 for the sequence. Though less than what they’d wanted, getting anything may have been a result of Ladd’s positive reaction to the preview. “We just cut down the number of weeks that we had to work,” Baker says. “I think at that point George wanted like seven monsters. Well, we were all fans of science-fiction films. All of us wanted the opportunity to show what we could really do, so we did a lot more work than we got paid for. We ended up with about six weeks to do as many aliens as we could.”

A few ILMers began construction of the alcove set on a small sound stage in Hollywood, while Grant McCune, Lorne Peterson, Joe Johnston, and others began photography of the miniatures on location. “I think there were six trips made to the desert,” Johnston says. “Four were made just to shoot the sandcrawler; on two others they took the landspeeder along for canyon shots. The sandcrawler was constantly breaking down: the tracks would jam, the tread would come off. The sandcrawler probably ended up costing more per second than anything else in the film, because it involved taking that model, a camera, and a crew of six guys out to the desert, where they usually had to spend the night. We left the model once in a van, and it got cold that night. We were in a motor home twenty yards away, but we could hear the pieces of styrene popping and cracking on the model.”

On the first trip one of the sandcrawler’s inner lightbulbs broke and they didn’t have a replacement; the second time it was too windy and cloudy; on the third trip the lighting exposure was done incorrectly; only the fourth shoot was perfect.

Lucas was leading the second unit, and had called in Mark Hamill for their pickups. Hamill was driving himself out to the location in mid-January, the Friday night before the rest of the crew left, when he had a bad car accident. According to Kurtz, Hamill was taken to County General and then, because of the severity of his wounds, to Mount Sinai Hospital. “They operated from about nine o’clock in the morning until about four in the afternoon,” Kurtz says. “I saw him at four thirty, and Mark said, ‘Oh. I’m sorry I got delayed. As soon as I get out of here this morning, we can go.’ He evidently had no idea what he looked like.”

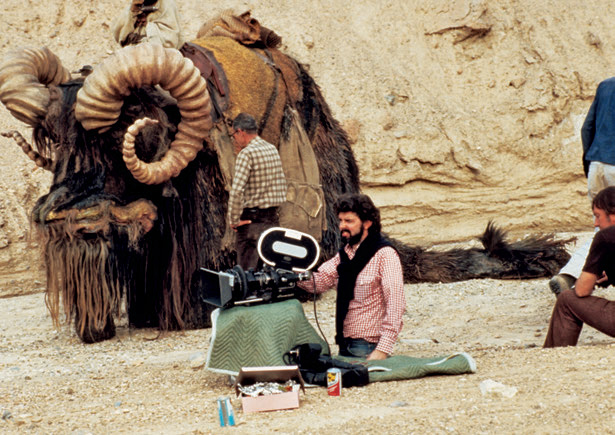

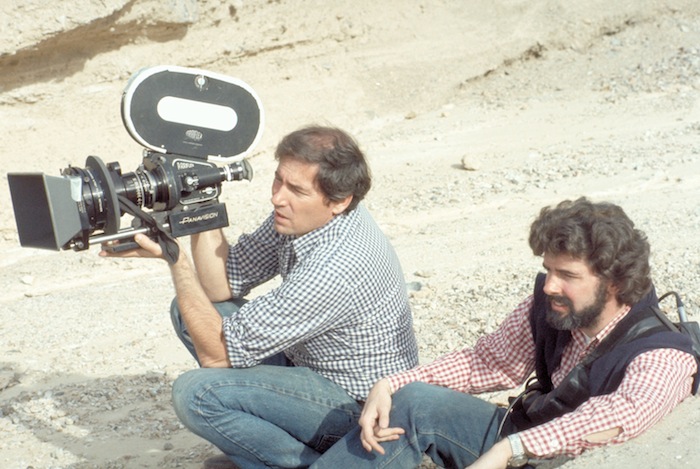

With Hamill out, Lucas and his crew set up their gear to capture footage of banthas, Tusken Raiders, and whatever they could. “There were a lot of things I wanted to shoot with Mark that we had to do without—bits and pieces, at least ten close-ups—but that was just fate,” Lucas says. “We ended up using a double for the landspeeder shot.”

“I was real concerned about the elephant wearing the bantha headgear,” Rick Baker says. “It weighed something like three hundred pounds.”

“We all fell in love with Mardji,” Lucas adds. “It was the first time she’d ever been out in the real world. They led her down to a creek in Death Valley and she just loved to play around in that creek.”

Fortunately, the elephant was good-natured and her shots were recorded without incident. Next up was the full-scale landspeeder, whose hovering effect had so far eluded production.

“We tried several ideas during filming, and none of them seemed to work,” Lucas says. “We finally tried using a mirror, and that came close, but it didn’t work, either. So when we went out to Death Valley, we redid the mirror and made it sturdier and made it longer, raised the car a little bit higher, and found a lake bed that had topography that was easier to work with. Then we shot it again, but that didn’t work because not enough care was taken to make the mirror and to get the speeder going fast enough. Finally, Bob Dalva came back with a crew and made it work. But he only got one shot, and we needed three. So then we sent another cameraman to get the final two shots using the same method.”

A student at USC with Lucas, Dalva had gone on to be one of the founding members of American Zoetrope. Another old friend of Lucas’s was Carroll Ballard, whom he’d gotten to know while making The Rain People (and who would direct The Black Stallion in 1979, with Coppola producing), and he became Lucas’s second-unit DP. “George did get some money to do some retakes,” Ballard recalls. “So I went out and shot out in the desert for about two weeks. Then we went back to Hollywood on a tiny stage right across from Kodak and shot the bar scene.”

John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, and Grant McCune in the desert of Randsburg shooting the sandcrawler miniature.

Doubles of C-3PO, Obi-Wan, and Luke in the land-speeder with its mirrored skirt for more pickups.

Transportation of R2-D2 and other material in a truck.

Kurtz, DP Carroll Ballard, and Lucas.

In Death Valley, Kurtz, DP Carroll Ballard, and Lucas shot pickups of the bantha (completely dressed).

DP Carroll Ballard and Lucas on location.

The “bantha” was named Mardji, a 22-year-old, 8,5 0 0-pound female Asian elephant, who was normally a resident of Marine World Africa U.S.A. (partially dressed, with the elephant trainer in the Tusken Raider outfit). “It took six men to build up [her costume] and they worked for a month,” says Ron Whitfield, director of general theater at the amusement park. The base was a “howdah,” or elephant saddle. The curving horns were made from flexible home ventilation tubing. Mardji’s shaggy coat was created from palm fronds, while the head mask was molded from chicken wire and then sprayed with foam to give it shape; the beard was made from horse hair. Although she was able to water-ski for spectators at the park, the bantha tail, made of wood and covered with thick bristles, gave Mardji problems—but her handler gave her apples, which compensated for the costume.

Printed dailies from the pickup shoot in Death Valley, mid-January 1977, of Mardji

the elephant dressed up as a bantha. Although Mardji has been trained to keep her

trunk hidden, it sneaks out here and there. (No audio)

(1:05)

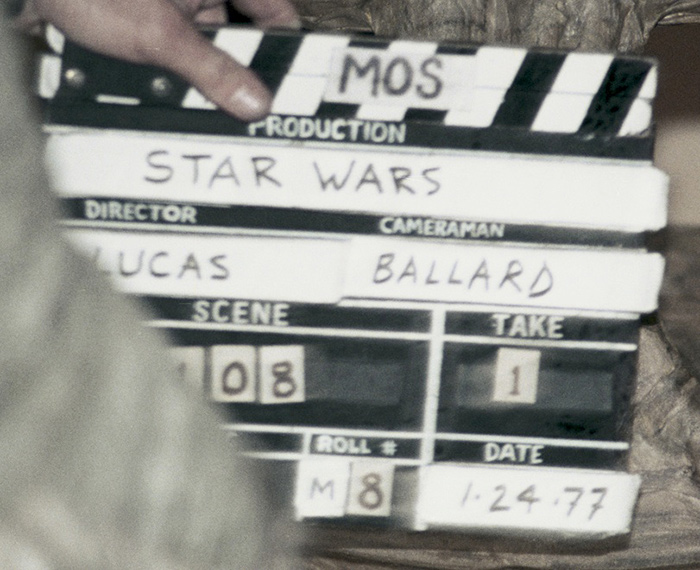

The inserts needed for the cantina scene took two days to shoot, at Dovington’s small studio on La Brea Avenue, on January 24 and 25, 1977. The new dialogue was typed up for reference on February 5, 1977:

Han and Chewbacca slide out of the booth, a slimy green-faced alien with a trunk snout pokes a gun in Han’s face. He speaks with an electronic intonation.

GREEDO

OOOH TAHTOO TAHT SOLO?

HAN

Yes, Greedo. As a matter of fact I was just going to see your boss. Tell Jabba I’ve got his money.

GREEDO

SOM BEJA LAY. SARA TRAMPEECA MOCK KEY CHEEZKA. JABBA WANINCHEKC BA WOO SHANEE TY WANYA ROOZKA …HEH, HEH, HEH, HEH. CHASK IN YAWEE, CHOOZO.

HAN

Yeah, but this time I’ve got the money!

GREEDO

EL JAYA KOOLKA IN DE KOOLY KUU SOO AHH.

HAN

I don’t have it with me …Tell Jabba—

GREEDO

JABBA HI TISH KEE!!! SO GUU RUUYA PUU YA YA OOR WAH SEE PATKEEKA KUU SHOO KUU PON WAH SCHREEPIO!

HAN

Even I get boarded sometimes. You think I had a choice?

GREEDO

DLAP JABBA, POOM PAH KOOM POTNEY AH TAH POM PAH!

HAN

Over my dead body …

GREEDO

OOHKLAY YUMA, CHEEZT OE KUU TOO TAH PREEZTAH KRENKO …YAH POZKA!

HAN

Yes, I’ll bet you have …

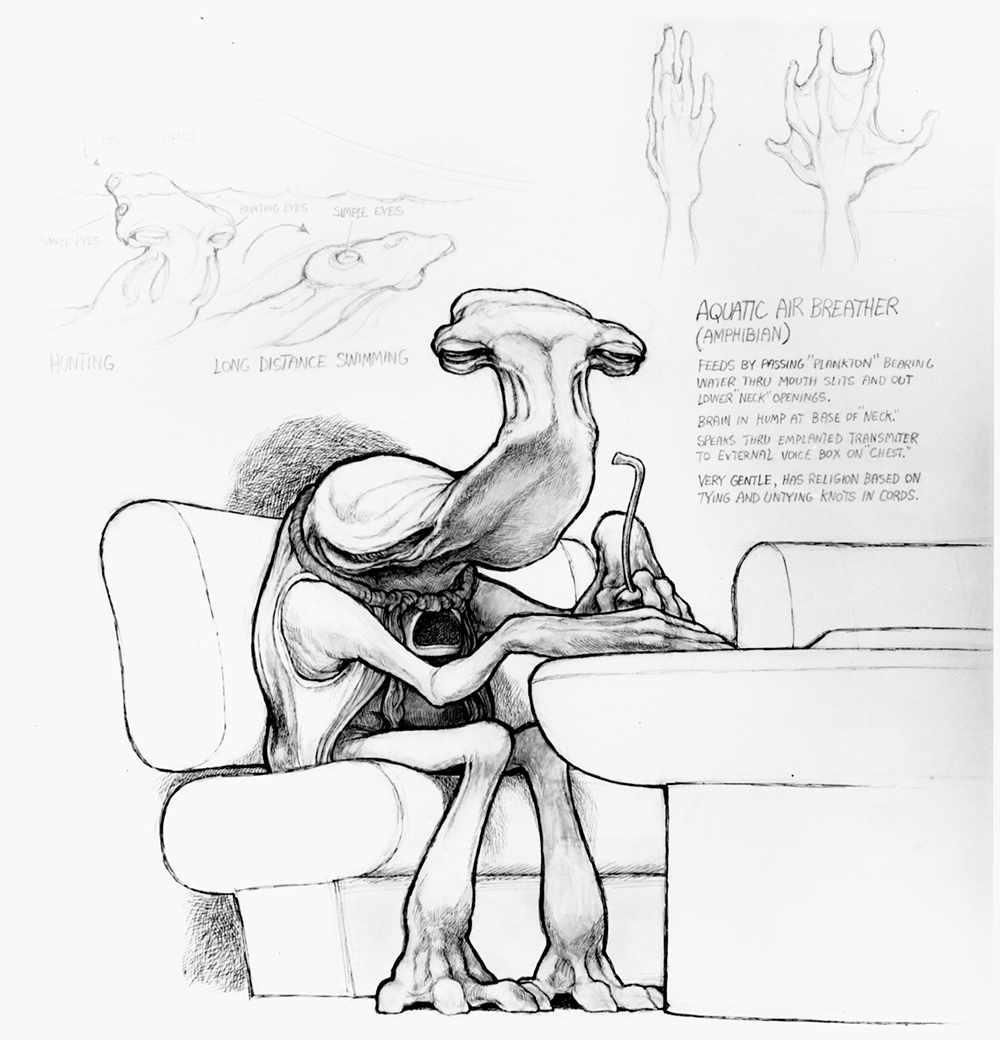

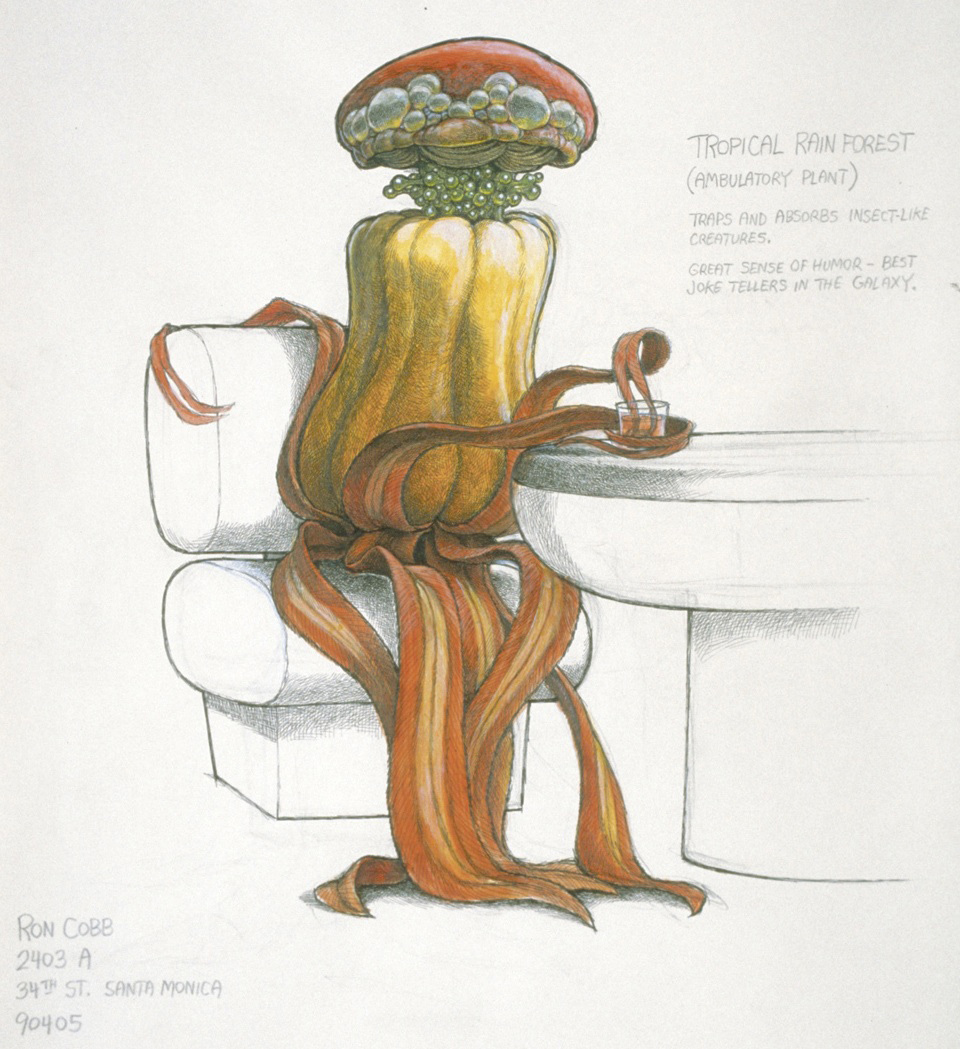

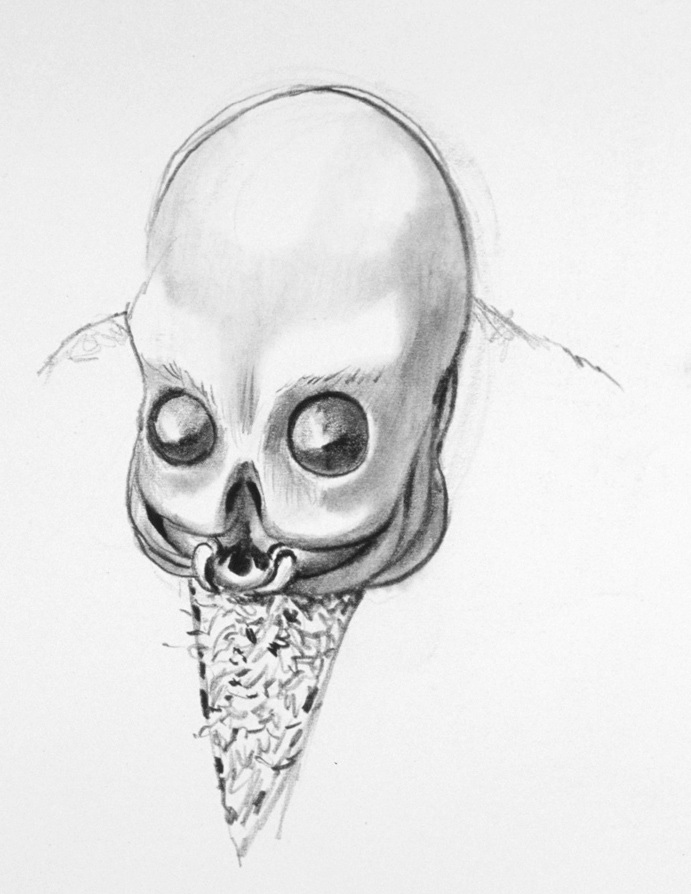

Back on September 30, 1976, McQuarrie had already started making sketches of aliens for the planned reshoot of the cantina scene. Ron Cobb also contributed a number of illustrations.

With Ballard on camera, Lucas shows how to handle a blaster during the cantina pickups in late January 1977.

The notorious “drooling arm” monster was a hand puppet that could generate goo on command.

Harrison Ford would loop his lines later, as only the alien, now referred to as “Greedo,” would be on camera. “George showed me the Greedo mask, which I think is one of the ones he liked the best of Stuart’s,” Baker says. “He said, ‘You know, we’ve got this mask, but with the person wearing the mask, it didn’t work. He was moving his head and it didn’t look like he was talking.’ Fortunately, it was made out of foam rubber, so Doug Beswick added a little mechanism that works the mouth. The only other thing we did was put in a mechanism to work the antennae. The funny thing is that the mouth mechanism broke just before they shot. It was real delicate. But somebody got the idea to stick a clothespin in the girl’s mouth. So she just had a clothespin between her teeth, which went to the end of the mouth on Greedo, and she just moved that around.”

The “girl” was Maria de Aragon, whom George Mather had recruited for the Greedo reshoot. “It was hot under the mask, and I almost lost my life because I was out of breath,” she recalls. “I started to make gestures that were out of the ordinary, and George Lucas noticed and made sure I got help. I had a very bad three or four minutes there.”

Another monster that caused gagging was the one known as “drooling arm.” As Phil Tippett explains: “I had some ideas for a really weird, gross thing, something that wouldn’t look like a man in a suit. You could just put your arm in this thing, like a hand puppet. The jowls would breathe in and out, and it had a line through its mouth that dripped red oozy liquid. They were preparing to do that shot, so I was trying to get it ready real fast, sticking the tubes in and getting all the gook ready, when Kurtz walked up and did a double take, and then said, ‘George, come here!’ And Lucas walked up and looked at it, too. He said, ‘That’s really a gross-looking thing! What kind of a rating do we have on this, Gary?’ ‘Well, I think it’s a PG.’ So then they said, ‘Yeah, let’s go ahead and shoot it!’

“Laine Liska was working on that setup with me at the time,” Tippett continues. “First George shot it a couple of times without the goo, because it dripped all over the tail and was messy. And then he said, ‘Well okay, let’s do the goo in this next take.’ On ‘Action,’ I put my arm in this creature and reacted to the ‘Wolfman’ and Lucas said, ‘Okay…Goo!…C’mon, let’s have goo.’ And I said, ‘Laine, quick, the goo!’ And Laine had this plunger filled with all this red goo, so he forced it really quick and it let out this really big, kind of farting sound—and all this goo went phoosh! Just everywhere! It was so disgusting! George said, ‘Cut, cut, forget it, that’s it.’ You know, just everyone got grossed out! So that’s the story of how the goo didn’t get shot.”

Lucas directing Maria de Aragon as Greedo, whose hands actually belonged to another alien costume. Lucas holds in his hand the telltale clothespin, as he explains to Aragon how she was to hold it and move it with her teeth to operate the alien’s mouth.

Lucas with Ballard prepares to shoot three cantina patrons at their table on January 24, 1977.

In February 1977 complex work was being completed at ILM at a good pace, but still under less-than-ideal circumstances. Aside from technical problems, personality issues had to be worked through during this particularly intense make-or-break period. Fox production head Ray Gosnell had intensified the studio’s crack down on the effects house, which had a significant impact on everyone as they tried to meet impending deadlines. It was still no sure thing that the film would be released on time in May, only three months away.

“I got into arguments with George over this and that and the other thing,” Dykstra says. “But it was predicated on what I consider a paradoxical situation. He was working incredibly hard and had the rest of the show to do, but at the same time he couldn’t understand why I couldn’t do things the way he wanted them done. We had a lot of discussions about how things should be done, but he was sick and he does drive himself pretty hard. It was a nightmare for both of us.

“I was another obstruction, because I had a lot of the film in my hands,” he adds. “And I was paranoid as hell. I figured that things were going on behind my back because Mather had been brought in. I asked, ‘Do I get to fire Mather, if I don’t like him?’ It was really unfortunate, because I truly really like George.”

“John has a tendency to talk everything to death,” Kurtz says. “You sit down to discuss a problem and he will explain to you for an hour why it won’t work. Well I don’t need that. I already know what the problem is. What I need is someone to say how we intend to solve it. So both George and I were rather frustrated about that. John assembled a lot of talent, but it was never run properly. It was like organized anarchy.”

“ ‘You’re not being cooperative,’ they would say,” Dykstra says. “You end up in the position of being the bad guy. But I’m not the bad guy! I’m not the bad guy! That’s what was crazy about that. That’s why I want to get out of doing this and do something else …”

Dykstra also had run-ins with Robbie Blalack in the optical department. “They fought a lot,” Kurtz says. “Blalack was able to composite that material with a minimum amount of dirt, with the very minimum of matte lines, but he and John didn’t always get along too well. Everybody has their problems and you never know for sure until you work with them. The trouble is, on a movie, you only have one shot at it.”

As for the ongoing technical puzzles, internal ILM memos attest to dozens of reshoots; misunderstood verbal and written instructions; the wrong negatives being used; starfields moving the wrong way; bad matte lines; and on and on. Nevertheless, throughout this whole period, only two people were fired, and no one ever quit.

Because he had shared his successive drafts with his close friends, Lucas screened his rough cut for many of the same sometime in mid-February 1977. Among the attendees were Brian De Palma, Matthew Robbins, Hal Barwood, the Huycks, Steven Spielberg, Jay Cocks, and a few people from ILM. “I usually show the rough cut to several friends and let them tear it apart and find out if there is anything I can do to improve it,” Lucas says. “So a week or two after I ran it for Johnny Williams, I showed it to them. Some were confused by it and some weren’t sure if it was going to work. Only Brian, as is his nature, said anything really negative about it.”

“I think we went a little overboard at that point,” Hirsch says. “We got so excited with the fresh material, the new monsters, and everything from the pickups that we overdid it a bit. And the opening prologue was still the one from the third draft, about what happens in the hundred years before the film, but Brian and Jay felt that it should be explaining what happened right before the film starts. Plus, Brian didn’t pick up the idea that Kenobi was turning off the tractor beam; Matt Robbins had the same problem. We solved that by just substituting some of the robot’s dialogue and by shooting one insert.”

A surprise birthday party for Grant McCune with women in a cake and homemade costumes featuring Paul Huston as Chewbacca and Joe Johnston as Darth Vader.

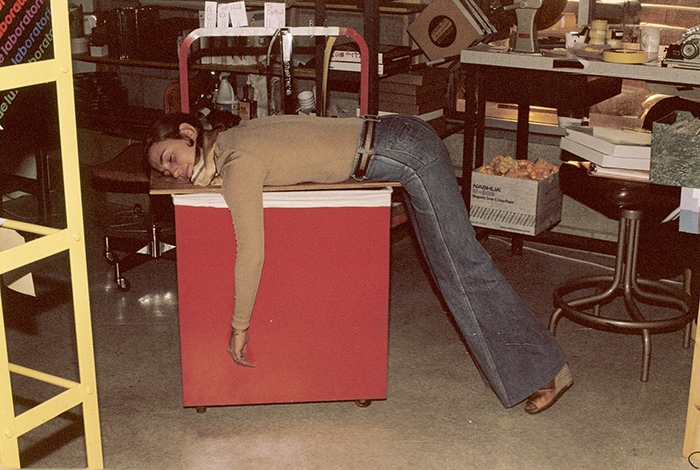

An exhausted Connie McCrum, film librarian.

Long hours led to Mary Lind and Paul Huston sleeping on the ILM premises.

The “cold-tub” crowded with (from high noon) Grant McCune; the daughter of ILM landlord Jim Hanna; Doug Barnett, Lorne Peterson, Paul Huston, bookkeeper Kim Falkinburg, Joe Johnston, and Mary Lind (in sunglasses). (Photos from the private collection of Lome Peterson.)

“The film was really not ready to be screened for anybody yet,” Spielberg says. “It only had a couple dozen final effects shots; most of them were World War II footage. So it was very hard to understand what the film was about to become. I loved it because I loved the story and the characters. But the reaction was not a good one; I was probably the only one who liked it and I told George how much I loved it.”

“Steven said, ‘This is the greatest movie ever made and it’s going to make a hundred million dollars!’ ” Lucas says. “The Huycks were dubious; they were worried about it and about me—but Brian was saying, ‘What’s all this Force shit?! Where’s all the blood when they shoot people?’ If you know Brian, that’s the way he is. He does that to everybody; he’s very caustic.”

“George has always invited honesty,” Spielberg explains. “He’s never said, Come see my movies to heap praise on me. He invites you to give your honest opinion, but Brian kind of went over the top in terms of his honesty. That night he and George had kind of a verbal duel in a Chinese restaurant, which was pretty amazing to have witnessed. But out of that conflict came a wonderful contribution. De Palma inspired the new crawl, which gave the audience some kind of story geography.”

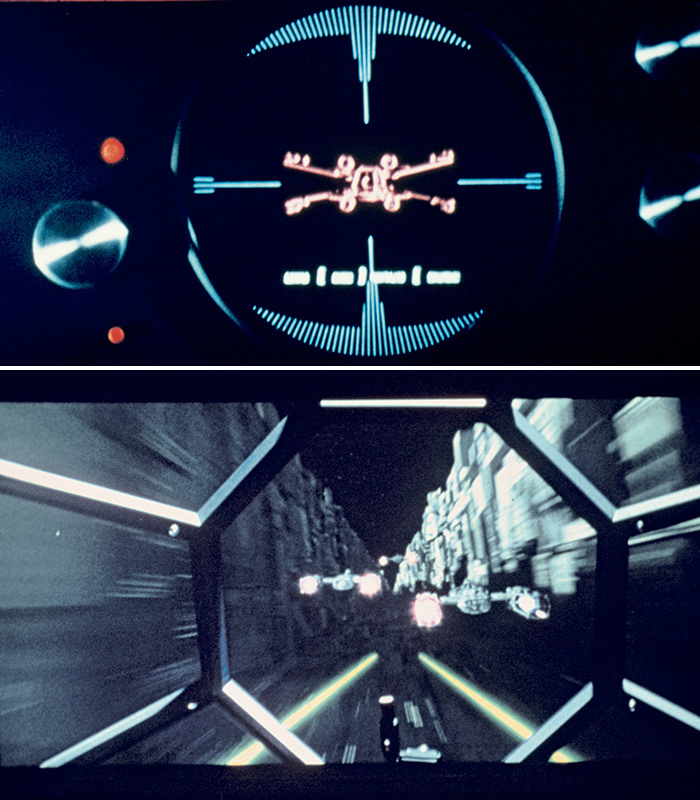

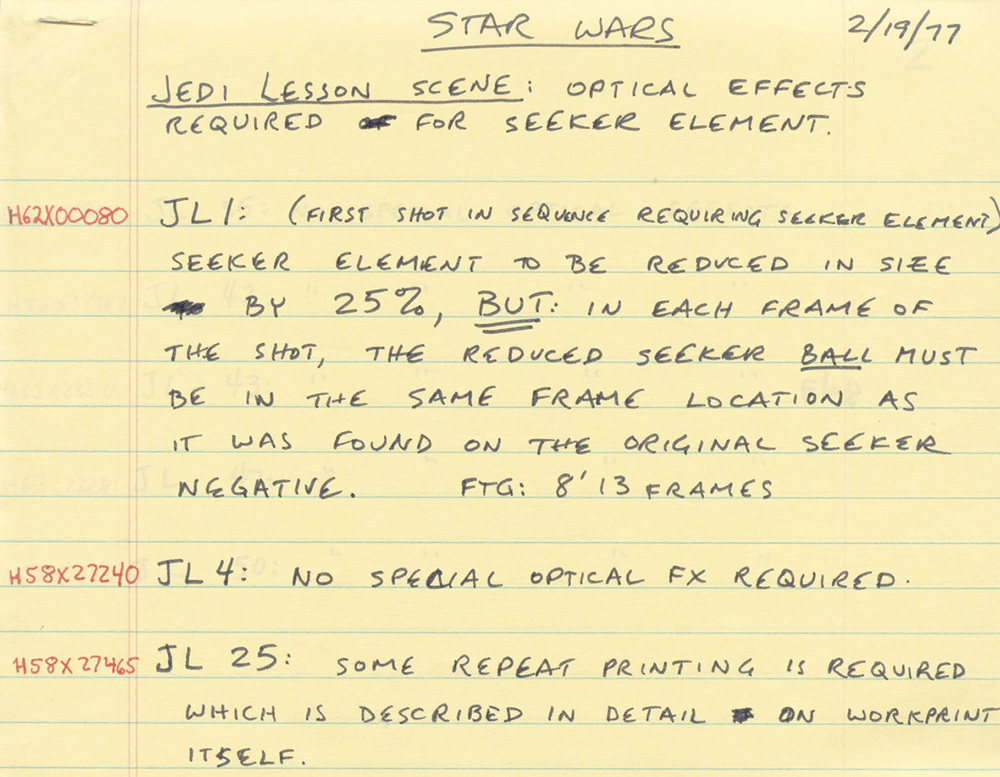

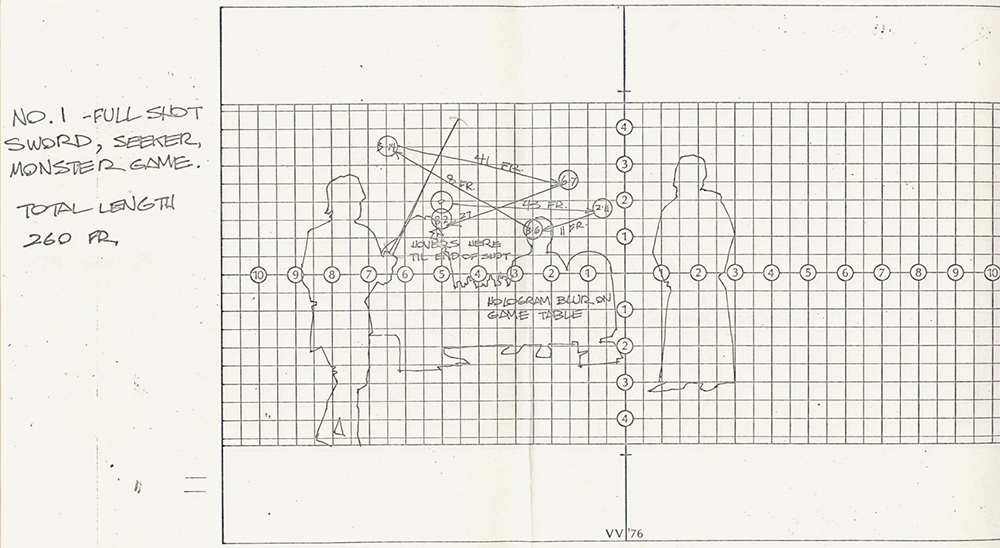

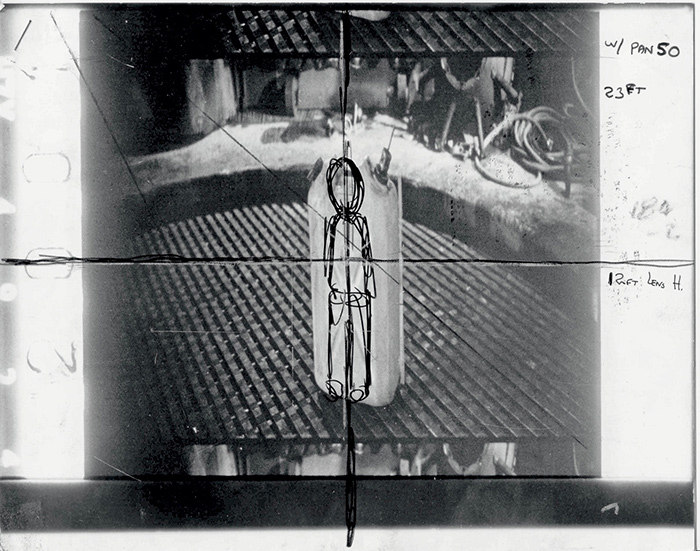

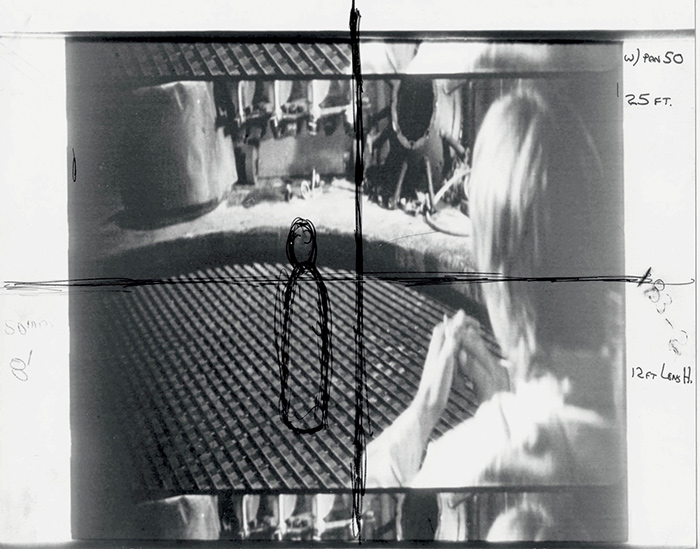

The seeker ball was made in the ILM model shop in two hours, and shot against bluescreen. But because all ana-morphic shots had been filmed with the 35mm production camera and not the Vistavision, the “Jedi Lesson scene” had to be sent to an outside effects house to be completed. Precise instructions per Lucas (dated February 19, 1977, with red tracking numbers in the margin) were written on how the shot should work.

Additional instructions were sent by means of a “Field Chart” that was unique to ILM.

Using 22 fields across, this diagram could be placed on a Moviola, then traced onto the appropriate frames, so the movement of the added elements could be calibrated exactly.

Final frame.

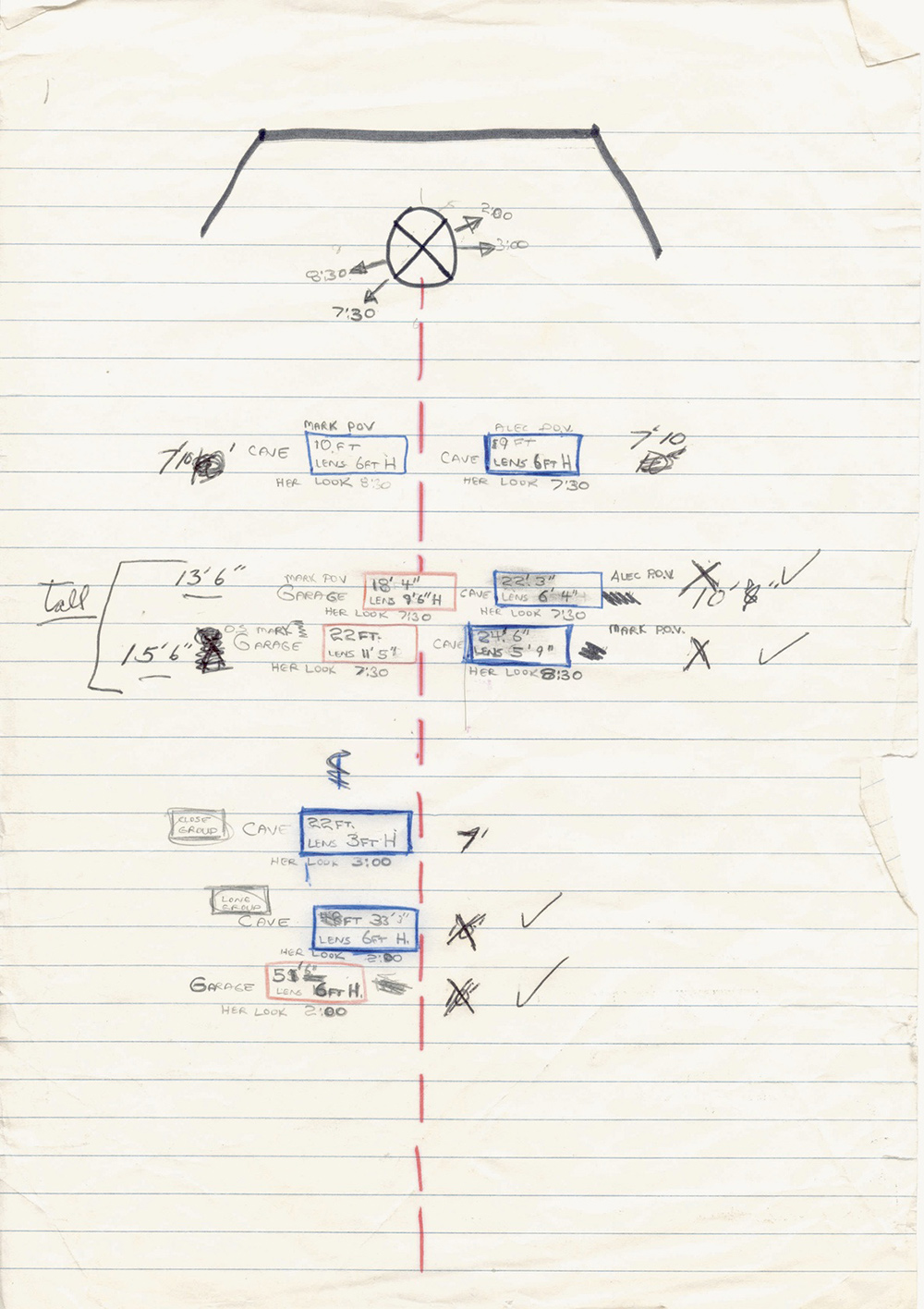

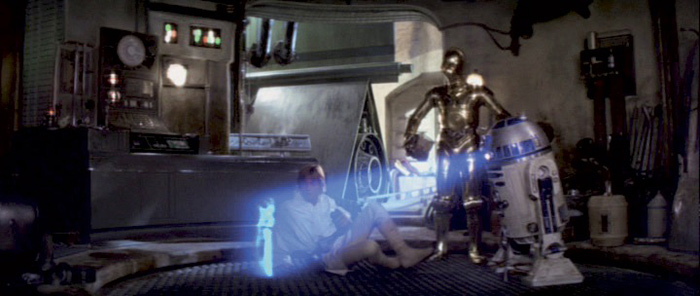

Carrie Fisher had performed her hologram dialogue while standing on a turntable. She was thus rotated and filmed from different angles that could then be composited into footage from the scenes in the garage and Ben’s house. Based on the various points of view, measurements were worked out. To help complete the shot, rough drawings were made on the 35mm squeezed anamorphic film.

“Brian was the one who actually sat down and helped me fix the roll-up, he and Jay Cocks,” Lucas says. “The next day we rewrote the roll-up; Brian dictated it to Jay. He typed it up and it got rewritten a couple of times after that.”

An important coda to the story is that Ladd, who was still quite anxious about the film, called Spielberg after the screening for his opinion. “He was very nervous and asked, ‘What do you think?’ ” Spielberg remembers. “And I said, ‘I think it’s going to make a fortune.’ ”

Martin Scorsese also viewed the film around this time, though not all the way through. “I saw pieces of it on the KEM, battle scenes with bluescreen,” he says. “My first reaction was that it was going to be tapping into this extraordinary revolution in technology, particularly in video games.” (In 1972 Atari had released Pong, which had become a sensation.)

Editorially, the collective feedback led to the cantina sequence being shortened. A subsequent screening for Francis Ford Coppola resulted in the only structural changes. “Francis thought that there was too much explanation in the beginning, I think,” Hirsch says. “So we moved the first scene inside the Death Star to much later in the film.” Originally the conversation between Darth Vader, Tarkin, and other Imperial officers took place in the second reel, right after C-3PO was reunited with R2-D2 in the sandcrawler; after Coppola’s reaction, the Death Star debate was placed after the scene in Ben’s cave, in the fourth reel.

“What that accomplished was really terrific,” Hirsch adds. “Before, you had no idea of the relative importance of who these guys were; you didn’t see the scene in its proper perspective. But once you’d followed Luke and picked up Ben, you knew how bad the bad guys were. And once we moved that one scene down, it set off a whole chain reaction of other things that had to be shifted. We dropped some scenes that didn’t serve much purpose, like the scene with Vader and one of his aides walking through the Death Star halls, where he was saying something about searching for the robots—we knew all that stuff anyway.”

“It was a little hard to judge,” Coppola says. “It was so filled with grease-pencil lines, and missing shots, and Japanese fighter planes diving … I didn’t know how to quite take it. I thought it was maybe a tad repetitive.”

“Francis saw it later on and his projector kept breaking down, so he saw it out of order,” Lucas says. “Carroll Ballard was living in Francis’s pool house at the time, and he saw it then, too.”

“George always has been unbelievably tight, in terms of how closely he plays his cards,” Ballard says. “He doesn’t reveal anything. Finally, he had a screening—and I felt so unbelievably sorry for George, because there were no special effects, just the performances, hardly any music … After the screening, I remember going up to George and trying to console him, saying, ‘You can probably fix it. Maybe we can do some retakes.’ It was just appalling. Had I been in the studios at that time, I would have pulled the plug.”

Richard Edlund prepares to shoot the opening crawl—which at this point was still the one written, with a couple of changes, for the third draft (with old logo).

From February 20 to 25, 1977, Ralph McQuarrie worked on the “Star Wars one-sheet roughs”—that is, the poster. While he’d been busy working on matte paintings of the planets and the occasional rough sketch for effects such as the one in Luke’s binocular shot, his duties were winding down—while the skills of a more experienced matte painter became needed. In fact, Harrison Ellenshaw, the son of celebrated matte painter Peter Ellenshaw, had been contacted nearly a year earlier.

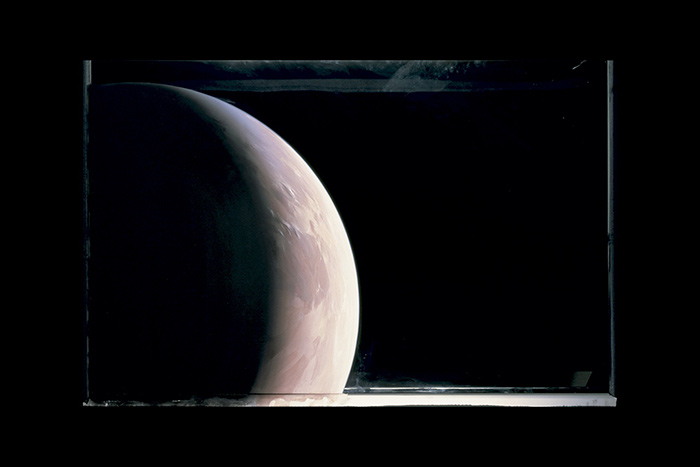

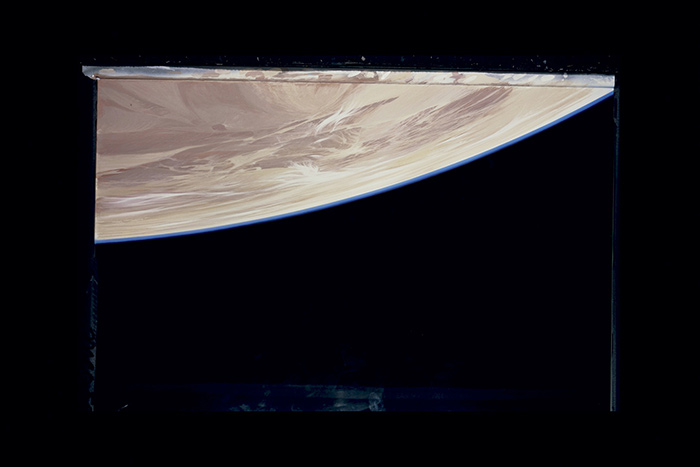

Back in the spring of 1976, McQuarrie had done several matte paintings of planets, including Tatooine. These were composited in creative ways with shots of miniatures so that, for example, a single painting detail could be used in several shots: with the escape pod, one or two Star Destroyers, and the Millennium Falcon.

Painting by McQuarrie

Painting by McQuarrie

“Jim Nelson said, ‘Hey, we’re doing a film called Star Wars. George Lucas from American Graffiti is directing—would you be interested?’ ” Ellenshaw says. “I said, ‘Yes, sure.’ This must’ve been January or February of ’76. Then about a week later Gary Kurtz came by with Ralph McQuarrie’s production paintings. I thought those were terrific. That looked exciting, and Gary said, ‘This is the look we want to get.’ When George got back from England, I met him and he completed the deal, because he was so full of his normal enthusiasm that I got wrapped up in it. I thought, ‘Yeah, we’re going to make some matte shots you’re not going to believe!’ ”

Many years before, Ellenshaw had at first resisted following in his father’s footsteps. But under the tutelage of veteran matte painter Alan Maley, he had quickly fallen in love with the art. By the time he was hired by Lucas, such was Ellenshaw’s reputation that even though he was heading up the matte department at Disney Studios, a deal was arranged whereby the painter received approximately $1,050 per week as the sole freelancer in the one-man company called Master Film Effects. “I was hired on the outside but Disney didn’t mind,” he says. “They’ve been very good about that and have allowed me to do an outside film on a rare occasion.” In fact, it was because Disney had allowed him to be considered for The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) that word had gotten around to Lucas that its matte department would do outside work, which until then had been true only for Universal.

The big push to complete the Star Wars matte paintings was during the months of February and March 1977. Ellenshaw worked an average of four to six weeks on each, but many were done simultaneously. To photograph the completed works, he used a stop-motion Bell & Howell camera box, originally made in 1912 for Disney, with torque motors and “funny added things,” he says. “It’s very simple, very reliable; it has a one-second turnover, which is what we used to film the painted matte shots combined with the live action. That’s what goes onto the negative, so that’s what goes into the film.

“The first three I did very roughly to see how they went,” Ellenshaw continues. “George loved them and that just boosted my ego. He said, ‘Wow, those are terrific!’ I was sucked in. From then on, it just continued. Normally, you like to sell the first version of the painting and hope there’s not going to be changes. But because of his personality, I really didn’t mind redoing them if he had changes, in order to make them as good as we possibly could.”

One of his successes was the great hall, which had been causing problems at ILM. “We turned it over to Harrison Ellenshaw,” Robbie Blalack says, “who used the actor elements, painting in the rest, and he did a really magnificent job.”

On March 1, 1977, a new actor took the stage at the Goldwyn Studios, albeit only for one day, and only as a voice. James Earl Jones had been chosen to do the Darth Vader dialogue, for $7,500. “George Lucas always wanted a voice in the bass register,” Jones says. “I understand that George did contact Orson Welles to read for the voice of Darth Vader before he contacted me. I was out of work and he said, ‘Do you want a day’s work?’ ”

“He was the best actor that I could possibly find,” Lucas says. “He has a deep, commanding voice.”

With Lucas’s prompting, Jones watched the pertinent scenes, studying his character’s lack of emotion, and ultimately investing in him a menace that would’ve been difficult to imagine before. Because Vader is masked, Jones didn’t have to worry about lip-syncing; he completed his work in about two and a half hours. “Vader is a man who never learned the beauties and subtleties of human expression,” Jones says. “So we figured out the key to my work was to keep it on a very narrow band of expression—that was the secret.”

Armed with Jones’s magnificently voiced readings, the director then utilized a technique that he’d originated with Walter Murch on American Graffiti whereby Vader’s lines were given a spatial dimension. “They did what they call ‘worldizing,’ ” Sam Shaw explains. “It’s a technique where they try to eliminate that ‘looped’ sound by playing the sound back through speakers in a regular room, so it has a natural presence to it, and then re-recording it.”

It was next Ben Burtt’s task to find the appropriate breathing sound to go with Vader’s voice. “He did about eighteen different kinds,” Lucas says, “through Aqua-Lungs and through tubes, trying to find the one that had the right sort of mechanical sound. And then we had to decide whether it would be totally rhythmical like an iron lung—that’s the idea, which was a whole part of the plot that essentially got cut out.”

Perhaps on the same day that Jones performed as Vader, Larry Ward did the voice-over for Greedo. Once again it was up to Burtt to enhance his readings to create a sound for the overly confident alien. “We had one word, which was just a person going ‘Oink-oink,’ ” Lucas says. “If you did it fast enough with the right rhythm and electric equipment, it sounded like a very bizarre language, but that didn’t work. So Ben got together with a graduate student from UC Berkeley, who is a real expert in languages, and he and Ben went through languages and languages and then they finally made up a language. Ben took it and edited it down, and we had the dialogue written out. Then we processed that electronically to give it a phasing sound and, well, it was a lot of work.”

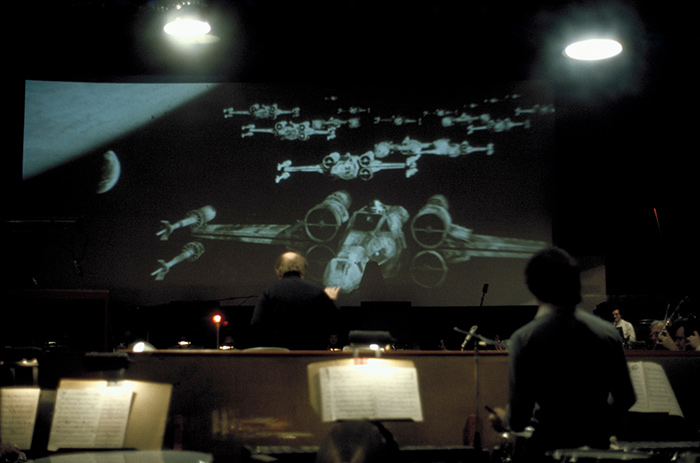

John Williams had worked quickly and was able to begin the soundtrack recordings on schedule in England on March 5, 1977. The decision to produce the music overseas had been presented to Williams as a fait accompli, probably due to continuing budget constraints and because the sessions coincided with the looping of the principal actors.

“We recorded at the Anvil Studios in Denham, which used to be the old J. Arthur Rank Studios,” Williams says. “It’s one of the most popular places to record music for film in London. It is out in the country very near Pinewood. It is a fine facility. I did Fiddler on the Roof [1971] there. Also did Jane Eyre [1971] there. So that was the logical choice. We had fourteen sessions with the orchestra, which represents about seven working days. A session is a three-hour sitting. Normally, we had a morning and an afternoon session. A couple of days we did three sessions, which was rough on everybody, because that is a lot of concentrating. With meal breaks that ends up being about a twelve-hour day.”

The total forty-two hours was performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, a first even for the veteran composer. “I had never used an organized symphony orchestra before for a film,” he says. “None of my assignments either coincided with the availability of an orchestra and/or the need for one. In this case we wanted a symphonic sound, and we were in London where great orchestras are available. In London you have a choice of four or five. I think they played beautifully, particularly the brass section. I think it has such nobility and such a wonderful heraldic sound. I think it really brings something to the film.”

Williams wasn’t the only one. Lucas had made the flight overseas to produce the sessions, and as he heard the first few cues, and saw the music’s marriage with the film he’d labored on for four years, he was incredibly happy. He even phoned Spielberg so his friend could hear over a phone directed toward the musicians half an hour of the melodies and themes as they were played for the first time.

What they both heard was one of the pinnacles in movie soundtrack history, ranking with Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo, Psycho, and North by Northwest, and Maurice Jarre’s Lawrence of Arabia, Max Steiner’s Casablanca, and Erich Korngold’s The Adventures of Robin Hood. Williams’s was an emotional score with operatic leitmotifs. “I think the music relates to the characters and the human problems, even when they are Wookiees,” Williams says. “This is the gut thrust of the thing in music—a very romantic theme for the Princess, a heroic march for the Jedi Knights—all of this material has to do with the fairy-tale aspect of it.

“I didn’t want to hear a piece of Dvoˇrák here, a piece of Tchaikovsky there,” he continues, commenting on a discussion he’d had with Lucas. “What I wanted to hear was something to do with Ben Kenobi more developed here, something to do with his death over there. What we needed were themes of our own, which one could put through all the permutations of a dramatic situation. This was my discussion and my dialogue with George—that I felt we needed our own themes, which could be made into a solid dramaturgical glue from start to finish. To whatever extent we have succeeded, that is what I tried to do.”

“I was very, very pleased with the score,” Lucas says. “We wanted a very Max Steiner–type of romantic movie score. There were a lot of little discussions about if this or that would make it go too far, would it be too much? I decided just to do it all the way down the line, one end to the other, complete. Everything is on that same level, which is sort of old-fashioned and fun, but going for the most dramatic and emotional elements that I could get.”

Whenever there was a break in the recording, Lucas would run to London to loop Alec Guinness, Mark Hamill, et al.—though at least a couple of actors read their lines at Anvil. Anthony Daniels arrived for voice-over work despite the fact that dozens of others had auditioned for the speaking role of C-3PO.

“It was primarily because of the fact that it was a British voice,” Lucas says. “I really wanted to keep the whole thing American. Tony had the most British accent, so I said, ‘No, I want to make him American because he is one of the lead characters.’ I wanted Threepio’s voice to be slightly more used-car-dealer-ish, a little more oily. More of a con man, which is the way it was written, and not really a fussy British robot butler. So I tried and tried, but because Tony was Threepio inside, he really got into the role. We went through thirty people that I actually tested, but none of the voices were as good as Tony’s, so we kept him.”

A recording of Lucas directing Guinness during ADR in London, England, March 1977.

Guinness experiments with various line readings for several different scenes, as the

recorder is turned on and off.

(0:51)

It’s possible that Lucas, often loath to part with an idea that he likes, was thinking of the used-car dealer who had been cut from American Graffiti by Universal and wanted to get the concept into Star Wars.

“With dubbing you get the beep, beep, beep—speak,” Daniels says of the audio cue. “It’s quite hard sometimes to deliver, for instance, a jokey line, all those bits about, ‘No, I don’t think he likes you at all; no, I don’t like you, either.’ But I enjoyed dubbing very much—I was very excited by what I saw on the screen in front of me. I’d often stop dubbing just to watch what was happening. I must say I think the banthas are one of the best things in it, and George of course won’t tell me how they were done. I realized, watching it, that I used to see George standing up against all these physically big people—surrounded by people trying to tell him what to do—and in fact he was getting his own way very quietly. And if he couldn’t get his own way, then accepting the fact. He really knew what he was doing.”

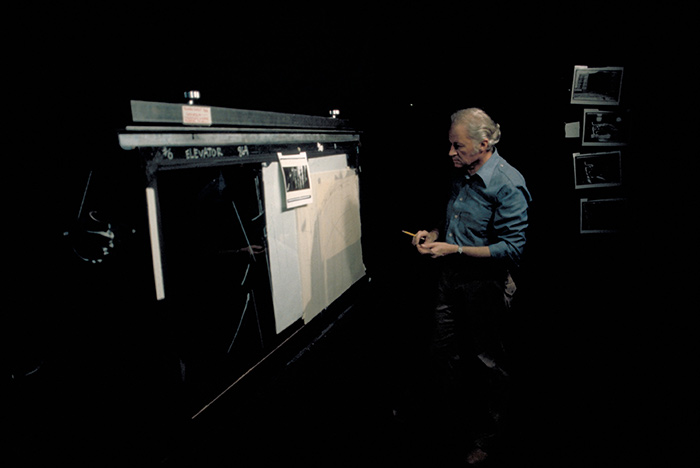

Harrison Ellenshaw at work on the Massassi temple matte painting

McQuarrie at work on the elevator shaft.

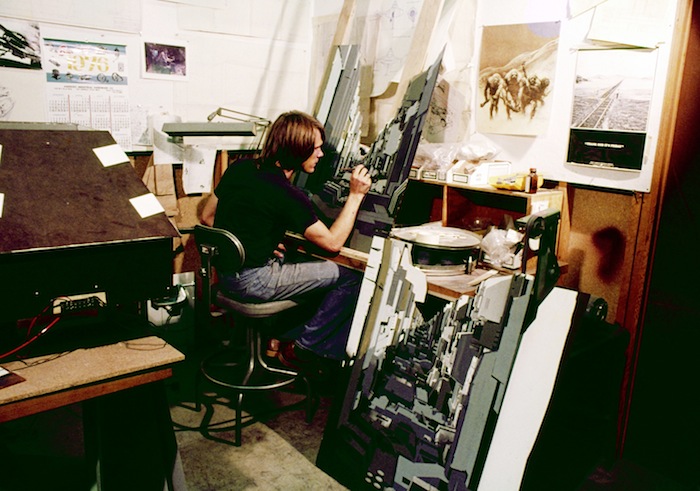

Joe Johnston at work on a Death Star trench matte painting.

Coincidentally, as Lucas left London, the looping and soundtrack completed, Ralph McQuarrie, his Star Wars work finished, arrived in England on March 25 to begin creating concept art for the first Star Trek motion picture.

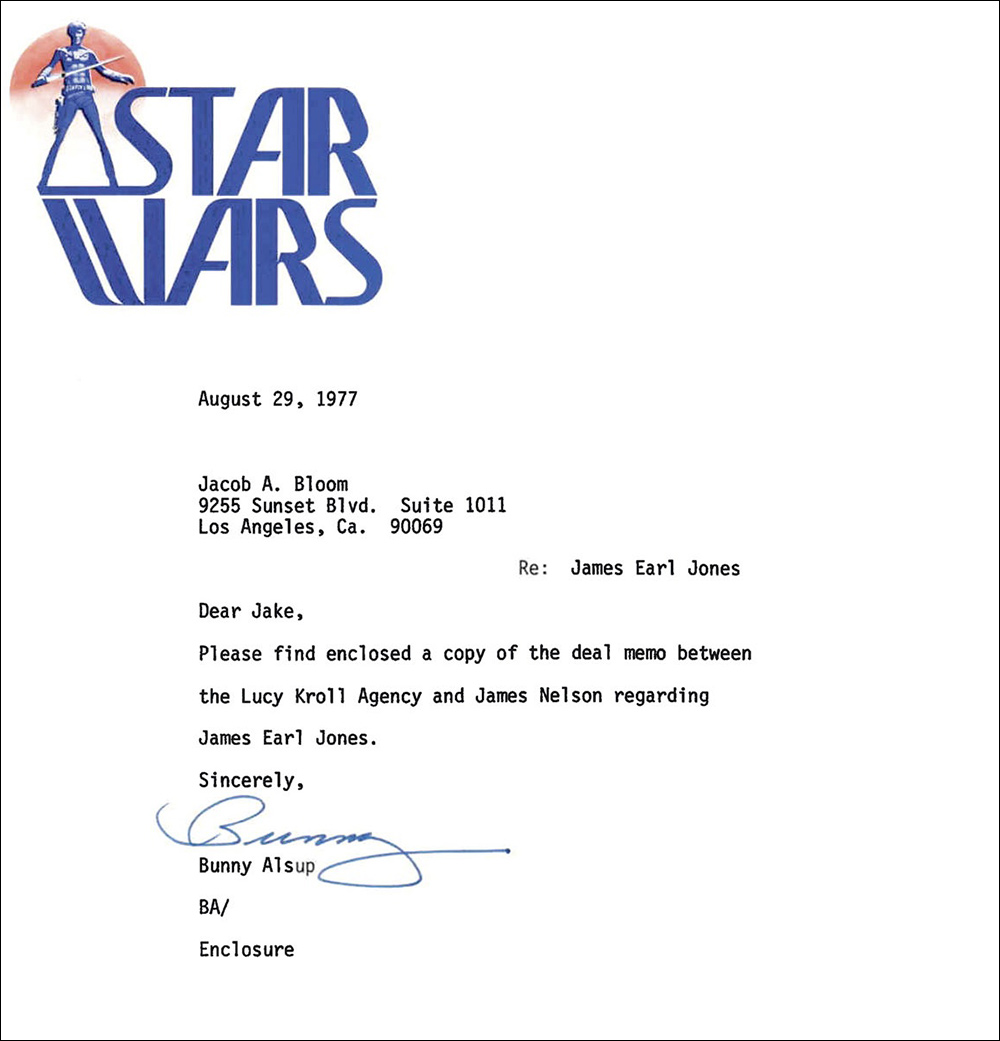

Just a few days before James Earl Jones took the stage, on February 25, 1977, a note from the Lucy Kroll Agency to James Nelson stated the agreed terms for which Jones would become the voice of Darth Vader.

Much later Bunny Alsup sent the deal memo with her own cover letter to Jacob Bloom per the hiring of Jones for the legal files on August 29, 1977.

John Williams conducting the London Symphony Orchestra to the rhythms of the film as projected above the heads of the musicians.

Sitting are John Williams and Fox music supervisor Lionel Newman.

Composer John Williams discusses the “Death of Ben” cue and the thinking behind his

decisions. (Interview by Lippincott, April 22, 1977)

(0:51)

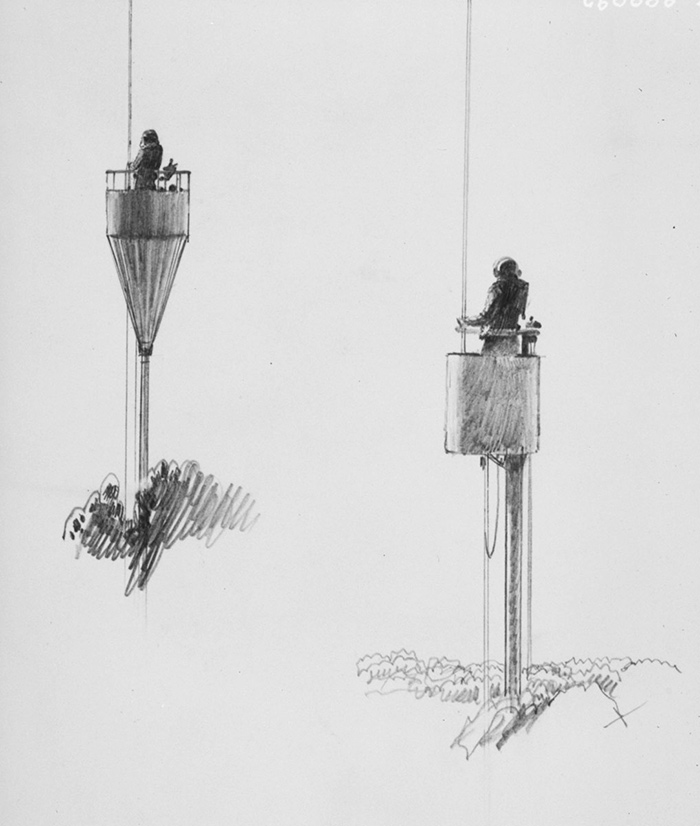

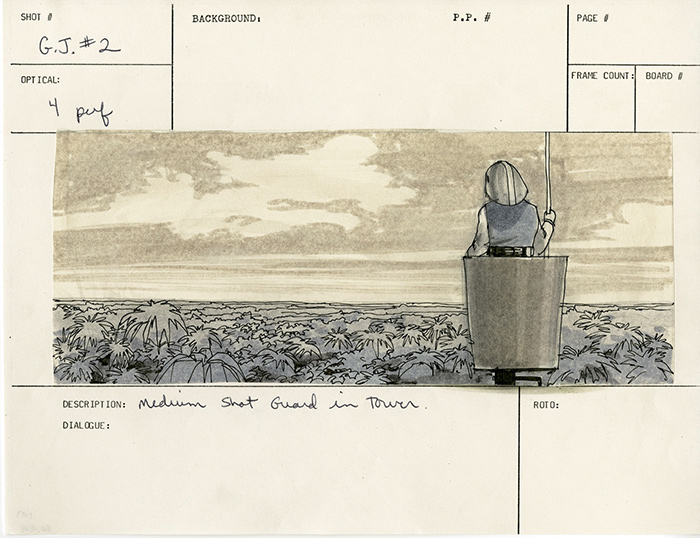

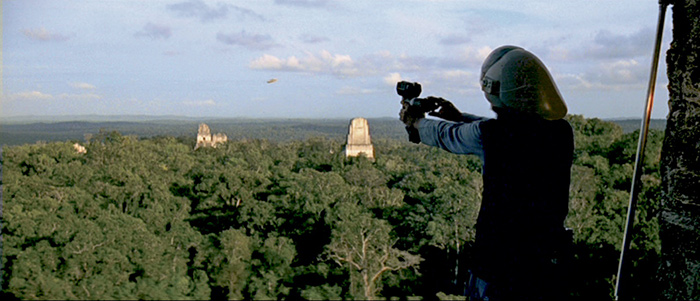

While Lucas was in England during much of March 1977, things were relatively calm at ILM, which meant that two camera crews weren’t necessary. It was thus the perfect time for Richard Edlund to lead an intrepid duo on an adventure in Guatemala. Their mission: to shoot the plates needed for the creation of Yavin, the jungle planet. Armed with twelve Joe Johnston storyboards as conceptual guides, Edlund embarked as the DP, with Richard Alexander to oversee the material and Pepi Lenzi as their translator and guide during a seat-of-your-pants journey.

“As a bonus, we got to take a little vacation, one week in Guatemala,” Edlund says. “Of course, we had to take 1,200 pounds of luggage with us. Pepi is the fellow that Ray Gosnell knew. He’d been on staff at Fox for fifteen or sixteen years as a ‘get-’em-there’ guy. He could speak ten languages—and he was so cool, he would just roll through customs.”

Hauling thirty-five cases filled with equipment (like the Technorama camera, built in 1931 as a Technicolor camera for Disney) through various airports, the trio eventually reached Guatemala, where they boarded a derelict DC-3 for the flight to Tikal. “Central America is a haven for used airplanes,” Edlund says. “It was really funky; oil was just dribbling down the sides of the plane.”

“We were sitting on this plane, which had about six seats that were covered with Levi’s,” Richard Alexander remembers. “There were big boxes and chickens, and there weren’t enough seat belts. It was ridiculous! But it was one of the best flights I’ve ever had—we flew only a couple of hundred feet above the jungle at about eighty miles an hour. The food was beans and rice and TV dinners, and it took like twenty-one hours to get there. We landed in a jungle; the ‘runway’ was just a strip of mud. It had been pouring, so there were puddles everywhere.”

Next stop was the Jungle Inn, so they loaded their gear on a Volkswagen bus and climbed into a jeep for the drive. “We set up most of the cameras in the hotel,” Alexander continues, “which was a series of little grass huts with rooms. It was really quite romantic—big peacocks running around, snakes slithering all over the place. It rained every now and then, but it was about ninety degrees; the humidity was so heavy that Richard was blowing smoke rings that would stay in the air for about twenty minutes.”

The next day eight guides led them on a scouting trip to the temples, about five or six miles through the jungle. “George had a picture in mind as to what he wanted,” Edlund says. “We had storyboards, and I had already shot the pirate ship that goes in one scene, so I had that clip to match.”

“Eventually we found the perfect shot to match the storyboards,” Alexander says. “We found the exact place on top of temple number three, I believe. It was the first ledge, which was probably a couple of hundred feet up, and it was only about six feet wide.”

“So we had to climb the highest of the old pyramids,” Edlund remembers. “This particular one was a ways away from the center; it was overlooking the others. So we climbed all the way up there with all the cases, all of the equipment; when I first got to the top, a little coral snake was in the middle of ingesting a bat in this cave.”

A McQuarrie sketch and painting from late 1975/early 1976. The latter was later extrapolated into storyboards by Johnston.

Though the small second-unit crew departed for Guatemala to capture the jungle footage, early in 1976 the planned destination was Mexico.

Richard Alexander, Pepe Lenzi, and Richard Edlund set up Lorne Peterson in the garbage can/lookout tower atop pyramid number three in Tikal, Guatemala (photo from the private collection of Lome Peterson).

Having found their location, Edlund hired two guards with shotguns to stay overnight with the equipment. “The first day with the baggage, that was okay,” Alexander says. “The second day, we got up at four o’clock in the morning. It was dark and just ridiculous.”

“I decided that on the second day, we’d get up real early in the morning,” Edlund says. “That way, we’d get to the top of the pyramid before the sun came up and get some shots in the early mist.”

One of the key shots consisted of a Rebel in his lookout nest—which was yet another ready-made prop. “The biggest box in our luggage was a trash can,” Alexander recalls. “The guard’s little post was really two $28 trash cans joined together and stuck on an aluminum pole with guide wires. We’d already tested it in the middle of Sepulveda Dam, before we’d left. As soon as I’d shinnied up the pole, the police came along and stopped to look at these idiots in a trash can twenty feet up in the air.”

After climbing pyramid number three once again, they took the trash can out of the crates, found chinks in the stones to keep the poles stable, and then placed the trash can on top of the poles so it had a commanding view overlooking the jungle. “We got it up there—but then nobody wanted to climb into it,” Alexander says. “So first a local did, and then I did—and I must admit, it was kind of scary looking down. The temple dropped away at an angle, but I figured that if I fell, I’d probably get stuck in a tree halfway down.”

On the third day model maker Lorne Peterson joined the trio in Tikal—and was immediately coaxed into the crow’s nest. Edlund also had him dress up as the Rebel who tracks the pirate ship with what’s supposed to be some sort of fantastic contraption, but which was really a Minolta spot meter, with a tube and batteries taped onto it like a gun, “to make it look sci fi.”

“I think we were actually shooting five days and were away eight,” Alexander sums up. “Getting back, we had a flat tire on our truck in the middle of the San Diego Freeway, during rush hour with all the luggage—that was the worst part of the whole trip.”

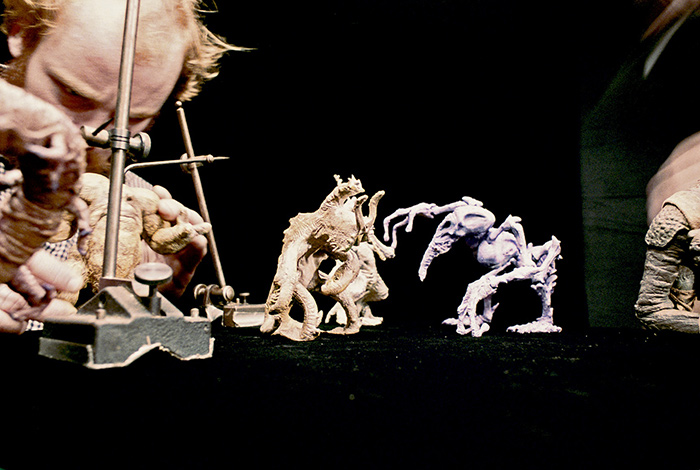

“George had said that he wanted some really gross-looking, ugly things for the cantina sequence to punch it up,” Muren recalls. “So Phil Tippett and Jon Berg made up some little sculptures that I thought might sell George on it; they were ideas for people standing on their heads and two people bunched up together in a suit. I brought them in and showed George, and he really liked them.”

He liked them so much that, after returning from England in late March 1977, he hired Tippett and Berg to do the chess set scene in which the droids match wits with Chewbacca. “Originally, they had planned to use little people in costumes placed on a giant chessboard,” Berg says. “But when they saw Futureworld [1976], which had already used the concept, it took the wind out of their sails. We had done some little clay figures for the cantina characters, and George saw those things and thought we could maybe do the sequence instead with stop-motion animation.”

“Lucas just said, ‘Make them about six inches tall,’ ” Tippett recalls. “Propulsion was one of our primary considerations, but he said, ‘I don’t care. They can slither and slide, or you can put wheels on them.’ So we had complete freedom to do what we wanted to do.”

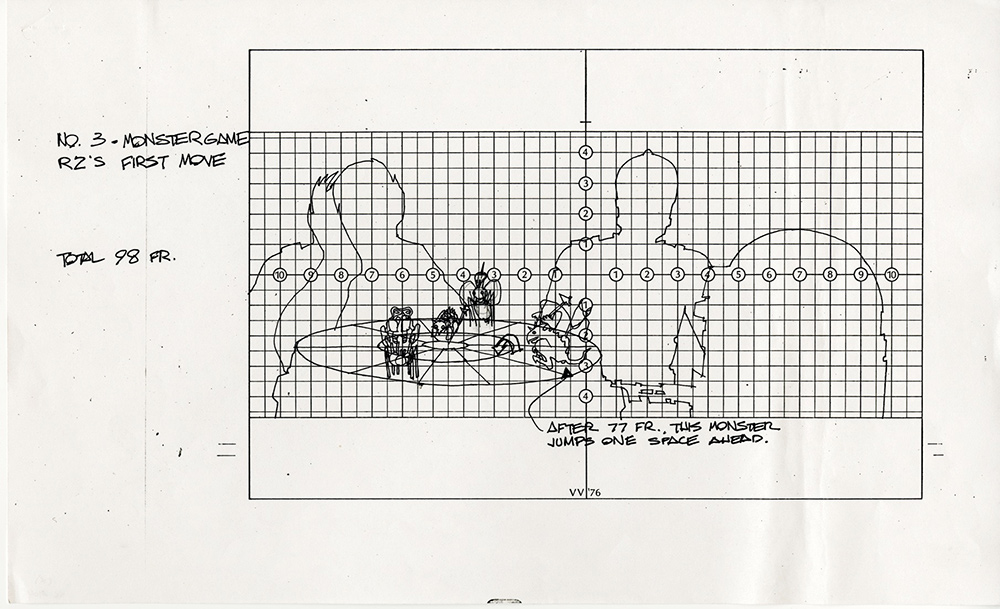

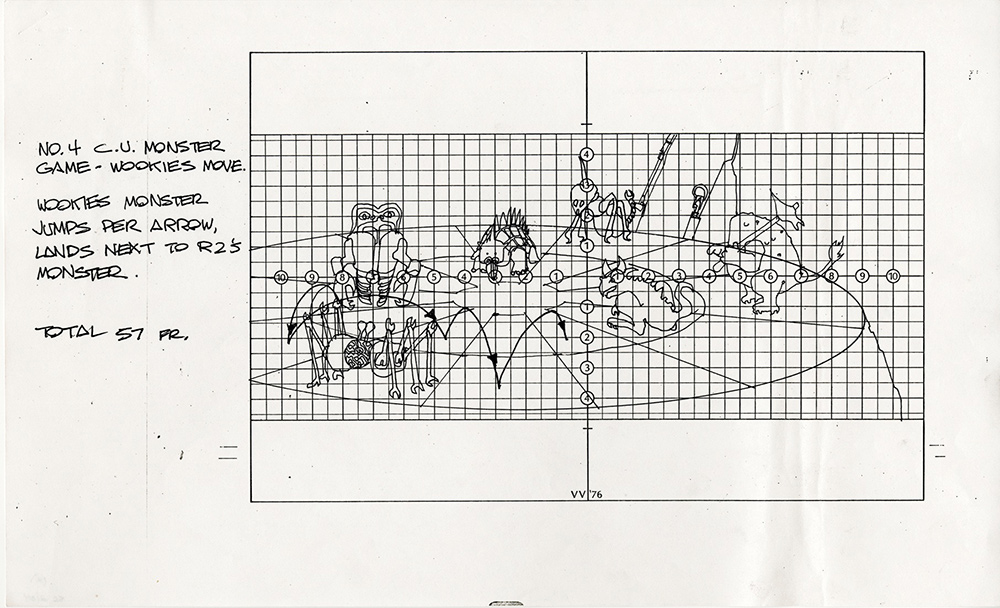

Because both Berg and Tippett came from the less elastic world of commercials, the liberty was invigorating and they started working intently on ten small sculptures—using latex, foam rubber, and plastic foam—while Grant McCune made the chessboard itself. “When we finally got the figures and the board set up,” Tippett says, “George came over that afternoon, before going over to do the sound mixing, and talked to us about what he had in mind. He blocked the sequence in, asking, ‘Could this hop out, or could this guy do this?’ And so we were working with him rather than having a preconceived set of ideas that he wanted very rigidly performed. It was a collaboration, and that was very exciting.”

“I set up the shots for them,” Muren says. “Jon and Phil did the stop-motion work, and the whole thing was done in a back corner at ILM. We did two shots that aren’t in the film, some low-angle close-ups on the figures, but George felt they just weren’t necessary. Once the audience had seen a thing in the movie, he didn’t want them to see it again later on.”

In order to match the backgrounds that had already been shot on 4-perforation film, Muren rented a regular 4-perf Mitchell with a squeeze lens. “Dennis was working on the night crew then,” Tippett says, “and he set up all the camera stuff and lighting against black velvet. We’d roll in about three o’clock in the afternoon and get shooting by about nine o’clock at night. We had about eight figures on the chessboard, so, for the master shots, we split the board right down the middle; Jon took four and I took four, and Jon did all the primary animation for the lead characters.

“We’d start with one figure on the left-hand corner and move one of his arms, his wrist, and his leg, and then go to the next one and bend his neck, and then go to the next one and flip his antennae, and move his feet—one forward, one backward—and then take one frame of film. Then I’d go back to the very first one in the left-hand corner and duplicate the entire process, trying to remember which way we were moving one of the legs, and so on. We’d end up getting out like eight o’clock the next morning, just at dawn.”

“We shot the chess game all in singles,” Berg says. “It takes more time and it’s harder. Boy, it gets rough when you have the number of figures we had.”

Despite the continuity difficulties, Berg and Tippett finished the sequence in five days.

Phil Tippett and Jon Berg posing the stop-motion creature sculpts on the black velvet, working out shots

Shots that had been preplanned to some extent using the grid/field method (shots 3 and 4 are shown, with frame counts, but the drawings indicate slightly different “monsters” from those that appeared in the film).

By the latter half of March 1977, the kaleidoscopes of editorial, ILM, music, and sound mixing were nearing their respective ends. Most of the effects shots had taken on their final forms, though many did not achieve what Lucas had originally envisioned. Often it was a case of abandoning ideas because either time or money or both were simply running out; other times it was a case of the ideal outstripping what was technically possible. “George’s visits started dwindling to Mondays and Tuesdays, and then just Mondays,” notes Edlund, “as we started getting closer and closer to the finish line.”

Lucas supervising work at ILM (with Rose Duignan; and with Kurtz).

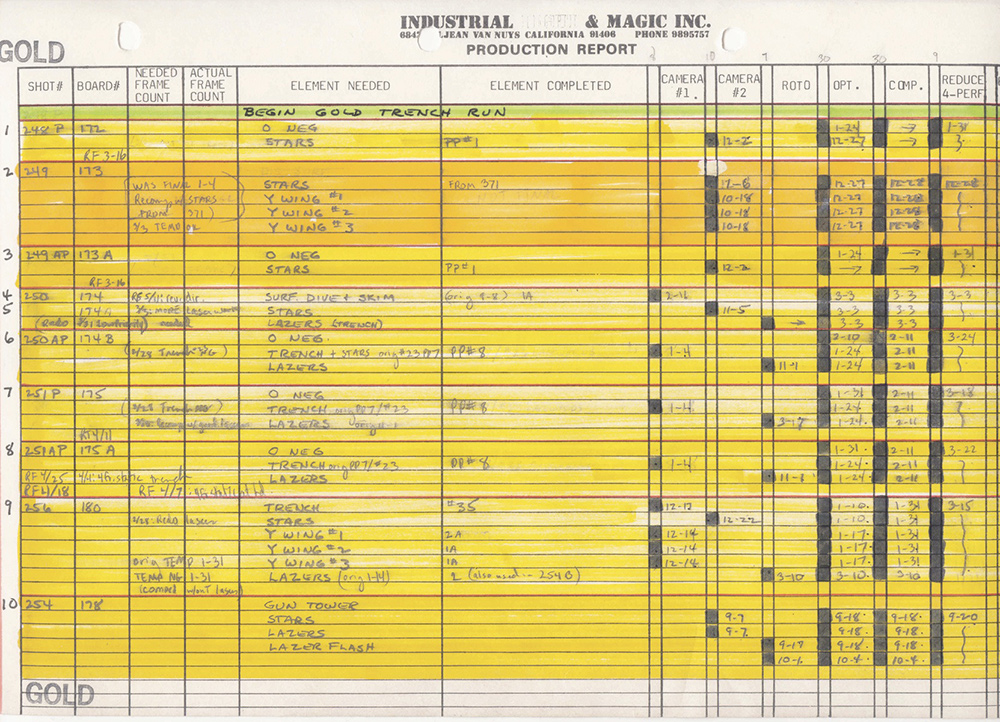

Special effects shots for the attack on the Death Star were tracked with ILM’s ongoing production report, from September 1976 to March 1977, with columns for elements, cameras, optical, compositing—up to “Okay G. L.”

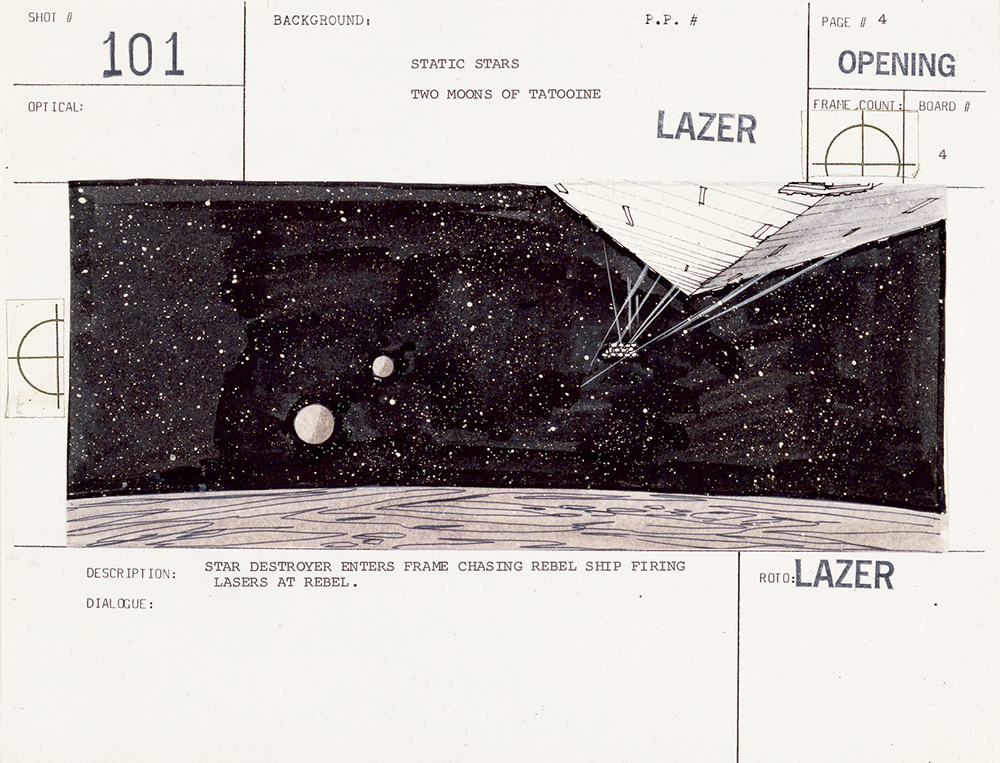

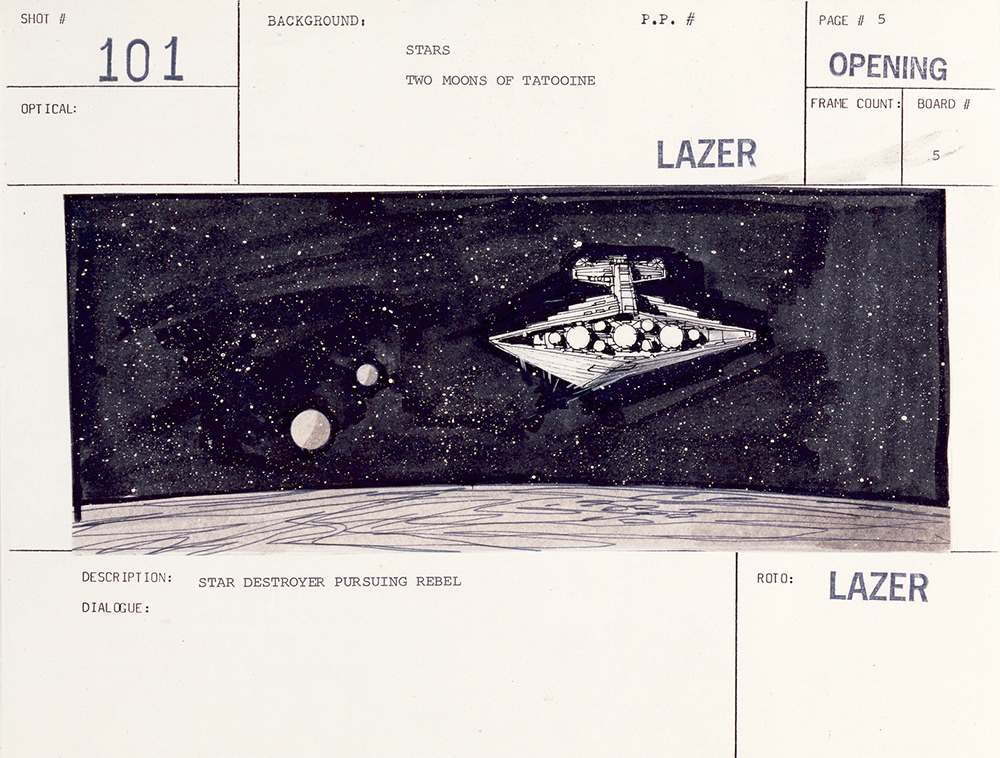

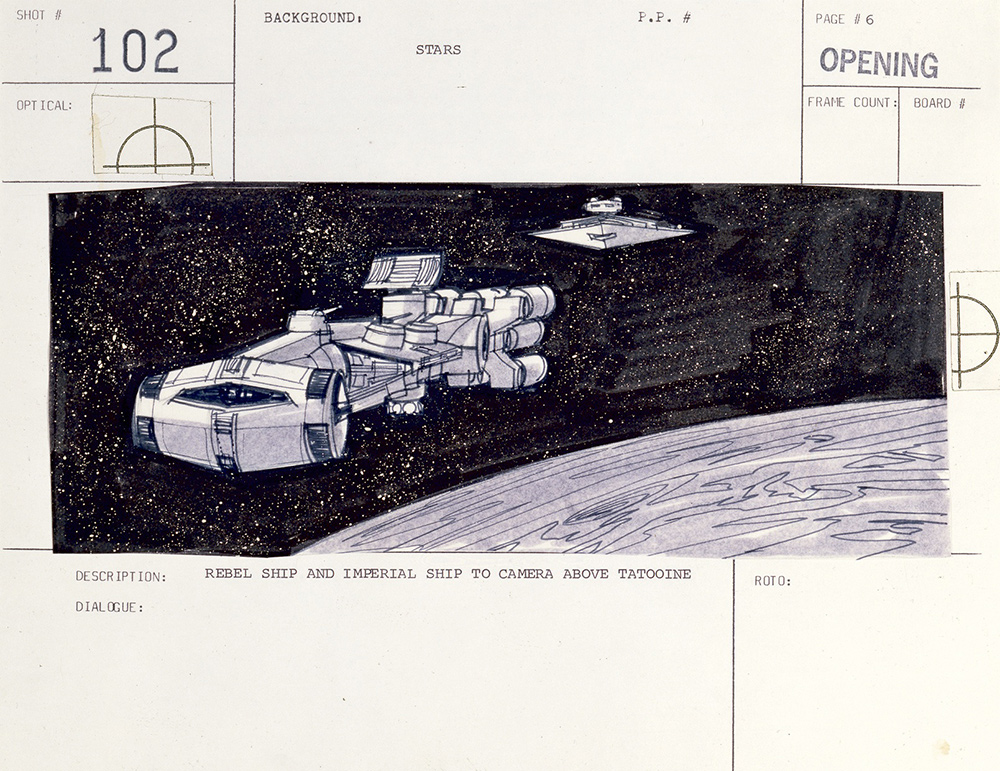

Storyboards by Gary Meyer, Paul Huston, Steve Gawley, under the direction of Johnston, show the opening shots designated “101” and “102.”

“I worked a lot on Saturdays toward the end to get the thing done,” Muren says. “We would shoot as many shots as we could in a row, Ken Ralston and I, without unloading the camera. That would save twenty minutes right there; if you’re doing that three times a day, you’ve saved an hour, which means one more shot for the day. That was the philosophy I had, because I didn’t see how it was ever going to be finished in time. But George compromised on his end and we compromised on our end. I don’t think quality was hurt too much, though it could’ve been better. It would’ve been nice if there had been another three months at the end of it—although we were pretty burned out.”

On the editorial front Lucas and Hirsch were still tweaking the film. “We constantly made changes to the movie,” Hirsch says. “It had made things difficult for Johnny Williams, because he’d been obliged to score the picture before it was locked. He’d even started writing music before we’d shot second unit. Luckily, our music editor Ken Wannberg was great in tailoring what had been designed for one thing to fit with another thing. He cut it and made it fit.”

“There was always this seesawing back and forth between the music and the sound effects,” Burtt says. “Music was dropped out of two places in the film. Initially there was a lot more music when Artoo-Detoo gets ambushed by the Jawas, but the scene played better without any music at all. There was also music originally over the sequence of the Dia Noga. Again it was more frightening and suspenseful without the music.”

With a close to final mix in place, another screening was scheduled. Though no doubt buoyed by Spielberg’s prediction, Alan Ladd had yet to get Twentieth Century-Fox’s sales team on board. Given the theater owners’ continuing indifference, Ladd would have an almost insurmountable task of booking Star Wars into movie houses without their support.

“Fox asked, ‘Can we bring up all the marketing and distribution guys? Because we have to start marketing the movie,’ ” Lucas says. “So they came over to Park Way from the airport in a rented tour bus. The room held about twenty-five to thirty people—and that’s the screening for which Laddie was holding his breath.”

“I was sitting poised by the phone,” recalls Ladd, who was back in Hollywood. “I had said, ‘The minute you’ve seen the film, will you please call me?’ So I was expecting a call … and expecting a call … But they didn’t call, so I thought, Oh, God, they don’t want to hurt my feelings. I broke my luncheon date because I still hadn’t heard from them. And I am waiting and waiting and waiting. I finally get a call—and they were absolutely ecstatic. Everybody was crowded into a phone booth saying, ‘The picture is extraordinary. I don’t even believe what I’ve seen!’ ”

“After they saw the picture the end of March, their attitude changed a bit,” Kurtz recalls. “They felt a lot more positive. They were much more relieved, and Ray Gosnell and the production office got off our back.”

Lippincott calls for a quick check-in as Lucas enters the home stretch, recorded on

March 24, 1977.

(0:51)

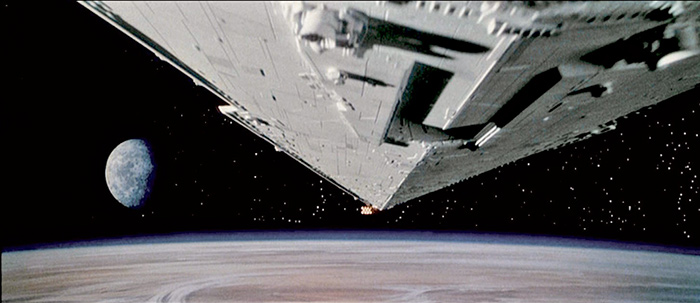

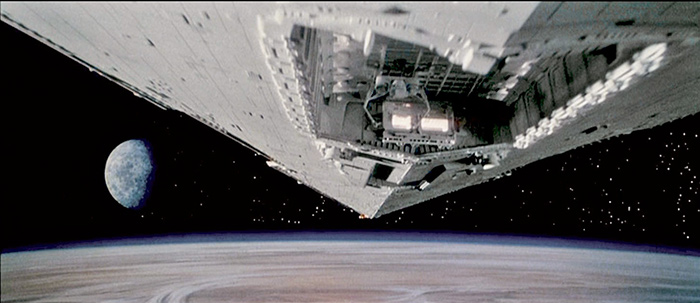

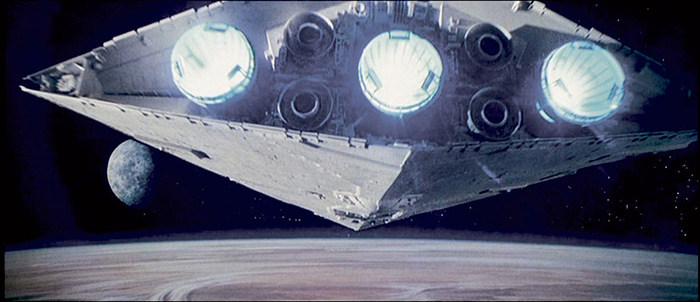

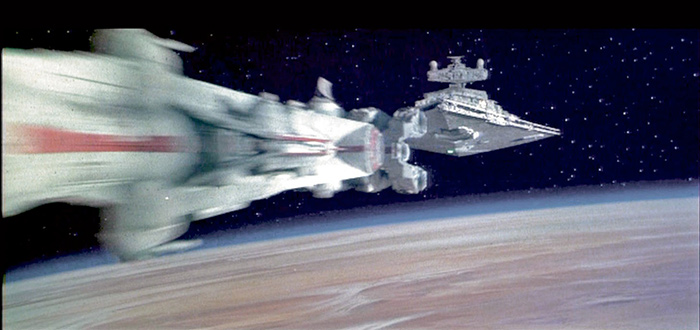

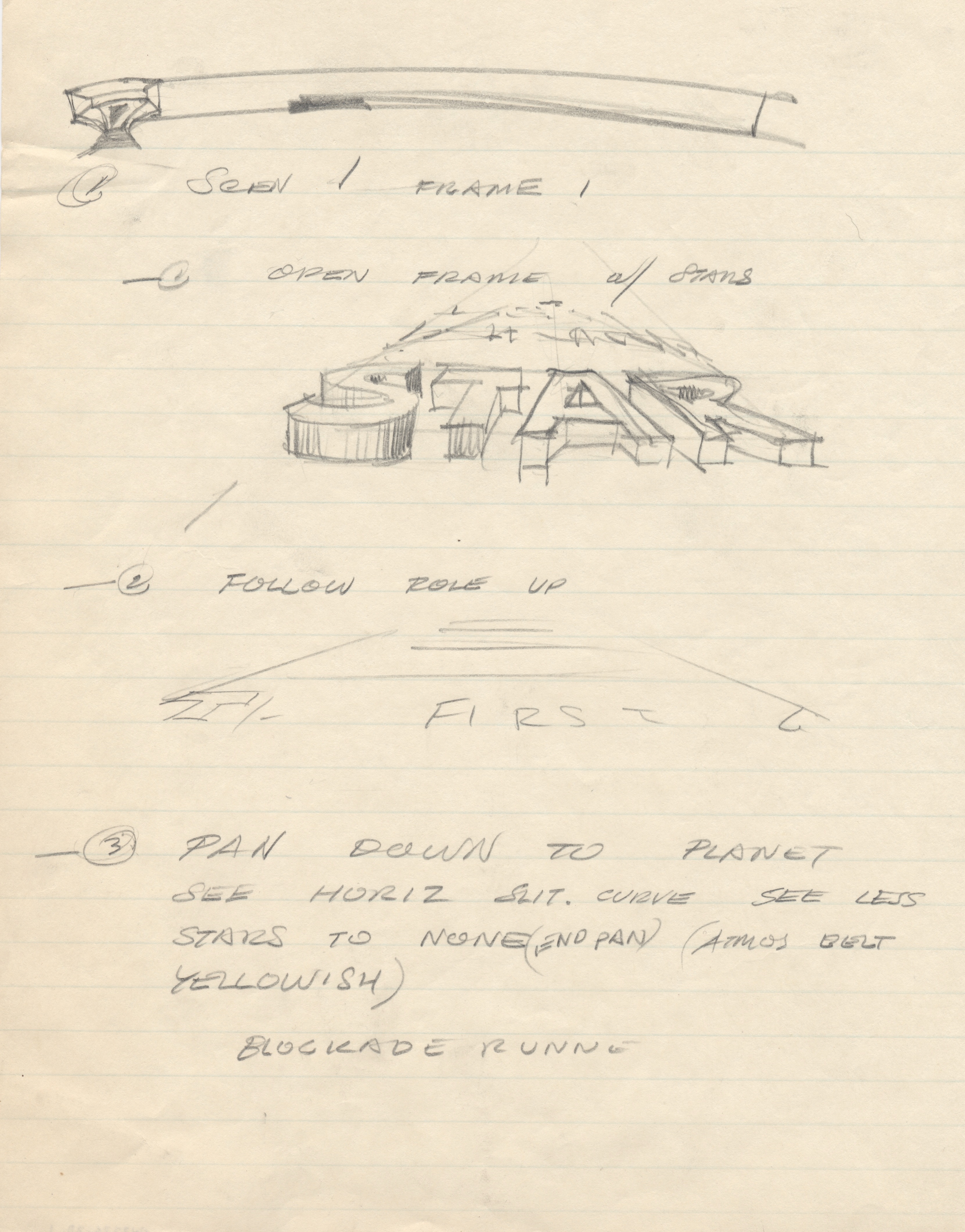

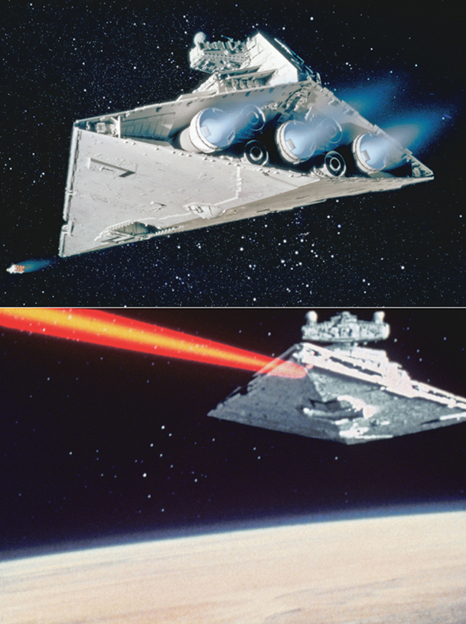

Intermittently from December 1976 to April 1977, Lucas, Edlund, and others at ILM were working on perhaps the most important moment of the film—the opening shot. “It’s the first two or three shots in the movie, where the big ship is chasing the little ship—that was my vision of the movie,” Lucas says.

Budget cuts and pared-down storytelling had reduced the number of Imperial ships from several to one. Other modifications and corrections sprinkle the ILM paperwork, which includes several references to shots 101 and 102, the two opening images:

DECEMBER 21, 1976: SHOT 102, REBEL BLOCKADE RUNNER NEEDS TO BE RESHOT. THERE IS A PROBLEM WITH THE MATTE LINE.

JANUARY 25, 1977: SHOT 102, PROBABLE RESHOOT OF STAR DESTROYER ELEMENT IN ADDITION TO DEFINITE RESHOOT OF REBEL SHIP. GL WANTS STAR DESTROYER ALMOST TWICE AS BIG, SO THAT IT FILLS THE SCREEN. REBEL SHIP WOULD GO OVER THE STAR DESTROYER FOR ENTIRE SHOT.

APRIL 8, 1977: SHOT 101: LAZERS ARE TO BE OPAQUED OUT OF TAIL OF MOST RECENT COMP (TEMP ON APRIL 7). ALSO, JOHN DYKSTRA IS GOING TO CHECK AND SEE IF ANY OTHER TAKES ON STARS FOR 101 ARE BETTER THAN SELECTED TAKE. JD MARKED ON PRINT WHERE LAZERS ARE TO STOP FOR FINA COMP (3 FRAMES BEFORE KEY #D6X89474).

Lucas also requested that the Rebel ship enter from the upper right-hand corner of the screen instead of directly overhead. “The opening shot, I felt, and of course George felt, was the most important shot in the show,” Edlund says. “It was the shot where everybody was going to have to make the ‘leap of faith.’ If everybody was just boggled by the opening, they would accept the stylistic integrity, the actual look of Star Wars. If I lost any sleep during the show, it was when I was worried we might blow it by making one shot that would make someone in the audience say, ‘Model!’ ”

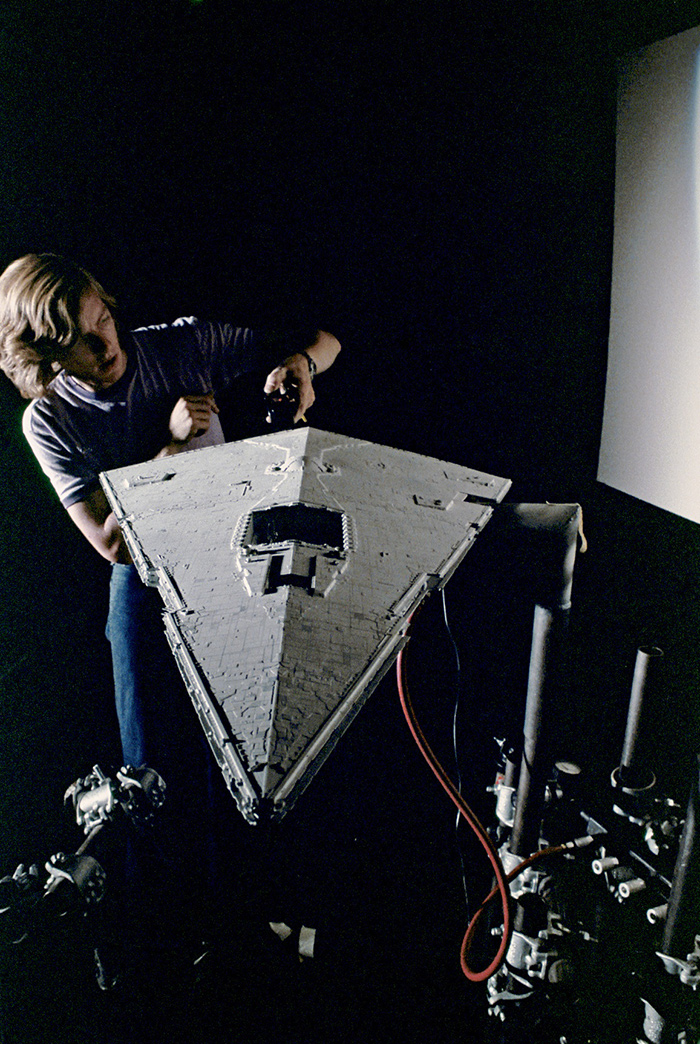

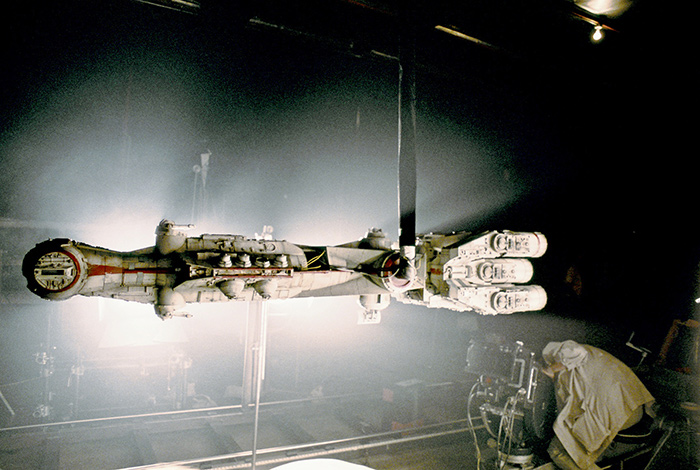

Richard Edlund and Jamie Shourt prepare the Rebel ship. “We built everything but the right top-side of the Star Destroyer,” Grant McCune says, “which wouldn’t be on camera—that became the access point for getting to the electronics and everything inside of it. The docking bay (with Doug Smith below) was very intricate with 20 to 30 light-bulbs, and extremely fine modeling using ten-thousandths-thick materials. David Beasley and David Jones detailed it, which took them about six weeks.”

The Rebel ship was shot with the Dykstraflex on the motion-control stage, with the help of John Dykstra, Bill Shourt, Dick Alexander, and Richard Edlund (with an ILMer on a ladder adjusting a fan). “We hung the rebel ship upside down [top two photos, to simulate the vacuum of space], and then we set up a pyrotechnic in one of the nooks behind the radar tower,” Grant McCune says. “We had time to put a pulse-motor in the central column and made the radar antenna spin around. The guns that had been made for the side of it [when it was the pirate ship] had been taken out and used on the Falcon, We lit it off and did about five or six takes with the high-speed VistaVision camera.”

A black-and-white dupe made for ILM of an early edit, winter 1977, reveals a different

opening crawl (which is having technical difficulties) and other interesting oddities;

some effects are done but not all, as markers drawn on the film indicate where animated

blasterfire should be added. (No audio)

(1:31)

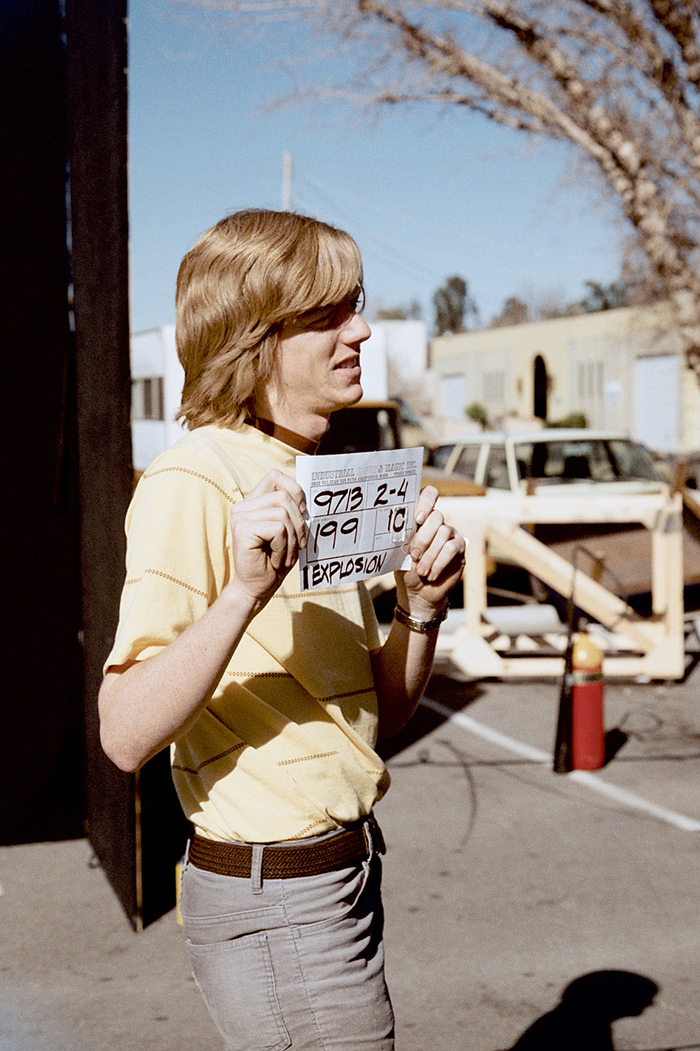

On February 4, 1977, Doug Smith held the slate for the day’s work on the Death Star trench and surface.

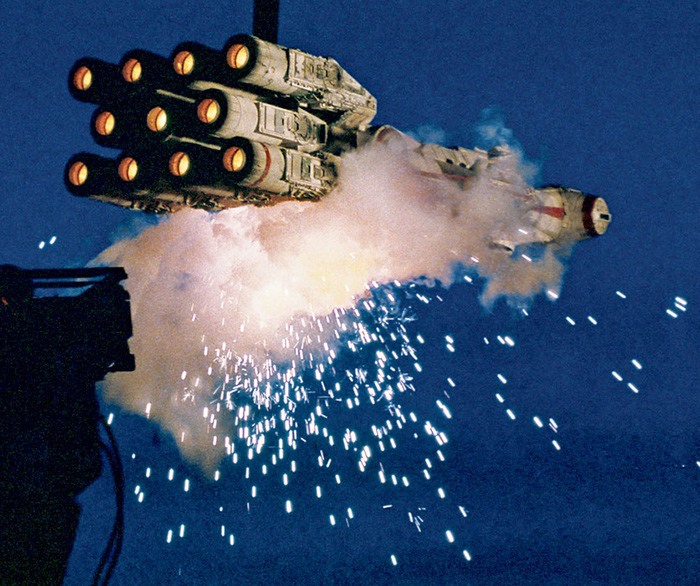

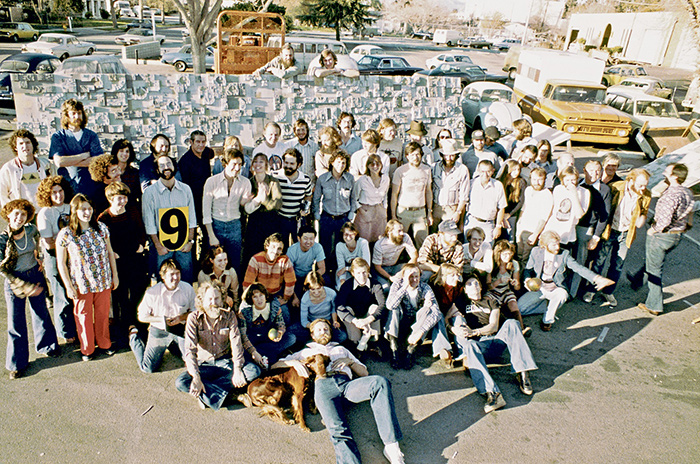

Explosions were shot outside in the ILM parking lot with Joe Viskocil supervising their preparation, and Edlund setting them off through cables.

It was also the opportunity for a group shot.

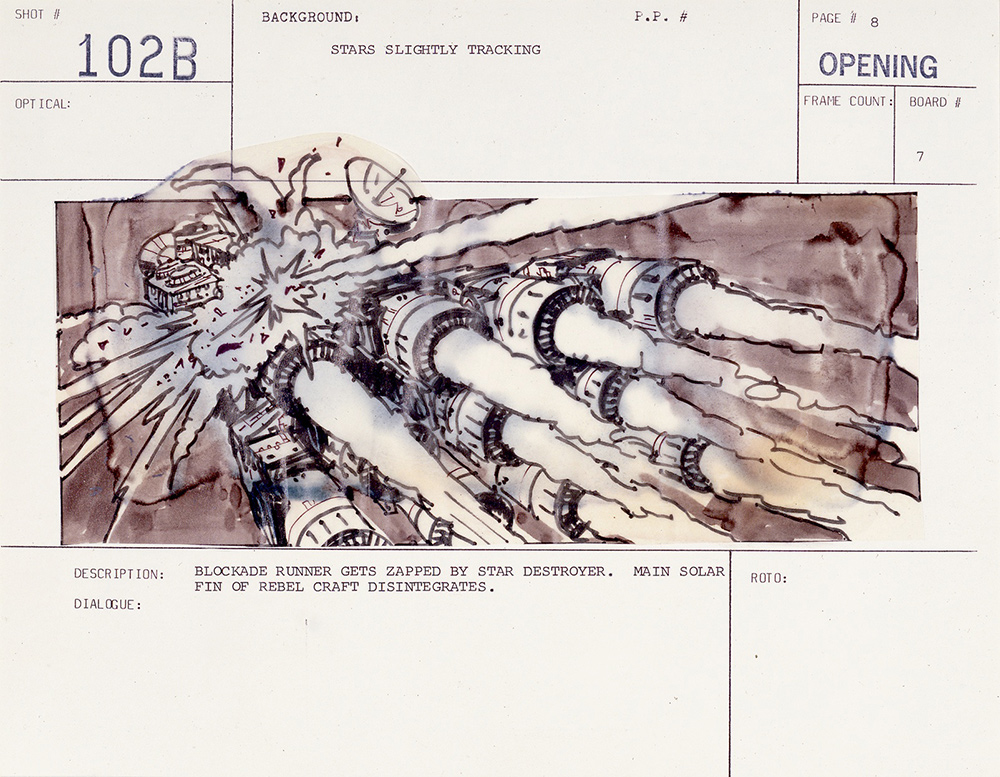

Much, if not all, of production’s anxiety concerning shots 101 and 102 did center on the models. The Star Destroyer was only about three feet long, but in the first shot it was going to have to fill the whole of the screen for a relatively long time—about fifteen seconds—and if it looked fake, it could ruin the film. The Rebel ship, ironically, was more like six feet long—but in shot 102 it was going to have to look as if it were being swallowed by the much smaller model’s underbelly docking bay, which was only five or six inches long.

“George at one point wanted to build a huge model for the Star Destroyer,” Edlund says. “We were getting to the point where we had to either do it or not, and he was thinking of revamping the opening, although he had his heart set on the Rebel ship coming in, followed by the big ship with ‘no cut,’ so that you got the entire effect of the big ship. But he was worried that the miniature wasn’t going to hold up. So I shot a test for him, by putting a tiny model on a piece of wire sticking out in front of the Destroyer, and just making a camera move on it against black.”

“George knew he wanted the ship to come in and to be big,” Kurtz says. “But he was worried that they could not shoot that with the small model, so we were talking about building a fifteen-foot section. Then Richard convinced him that with the right lens and angle, we could make that ship look really large. He tried it a couple of times, with a couple of different lenses, and finally George reluctantly agreed that it might work right, but we put that on the back burner as a potential redo.”

“We knew that the Star Destroyer was going to be in that opening sequence and we knew that it was going to have a real slow, close pan by it,” Johnston recalls. “And at that time we had some extra people from the model shop, so we just put two guys on detailing the Star Destroyer, detailing for weeks, especially on the docking bay.”

“Richard had to make the six-foot Rebel blockade runner appear to be about one-tenth the size of the three-foot Star Destroyer,” Blalack says, “and that had to be handled by optics, choice of lenses, and choice of shooting distance. We wanted to improve on that one, but we never got that shot right.”

“On shot 101 I used four synchronizers, two sawhorses, and a door,” Lind says. “We had so many separate elements—stars, large moon, small moon, horizon, Rebel blockade runner, mother Star Destroyer, two different elements of flak, two different elements of lasers, plus all the mattes for the planets. There is no synchronizer that can take all of that at once, so what you do is you find a four or five gang-sync and hook them all together.”

Following the many modifications, experiments, innovations, and ruses, Lucas signed off on the two shots in mid-April 1977, and then the audio elements were mixed in. “There were a few places in the movie where the music and the sound effects conflicted,” Burtt says. “One of the first places was at the very opening of the film, when the first spaceship flies overhead. We had always wanted to have that sound effect of the spaceship come exploding through, and be a big shock on the audience’s ears. However, the music composed for that point was also very loud, and was of such spectral composition that it camouflaged the explosiveness of the sound effect. We were never able to quite achieve the right blend there of music and sound effects, so we compromised, half and half of each.”

Lucas chose a light blue for the first words on the screen. “I wanted it to be less of an impact than the yellow STAR WARS,” he says. “I wanted something very quiet there. I think we went back and forth with green, which was put at the end. The beginning and the end are the earth colors, while the title and roll-up are more dramatic. The beginning is the fairy-tale part of it, so I wanted a quiet statement—I’m going to tell you a story: Once upon a time, there was a boy who lived on a planet…”

For the opening image, the models were composited into a shot with Ralph McQuarrie’s matte painting of three planets.

A handwritten page outlines the opening, roll-up, and pan down to the planets.

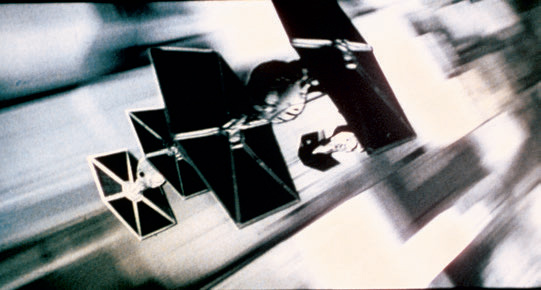

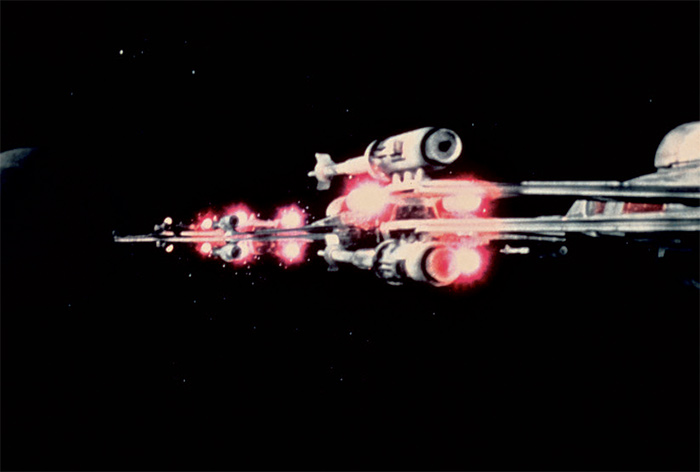

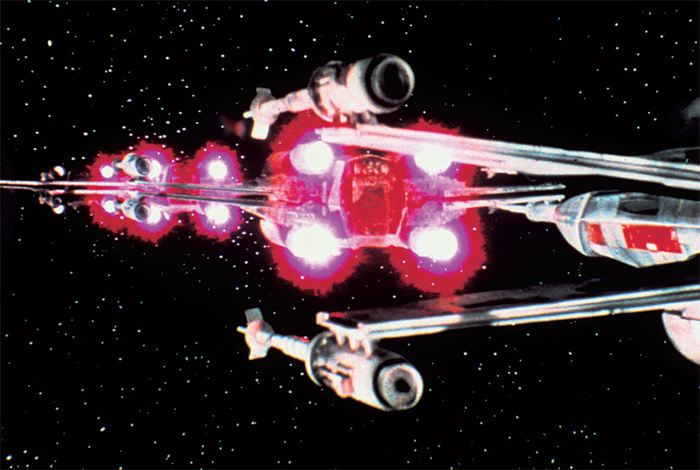

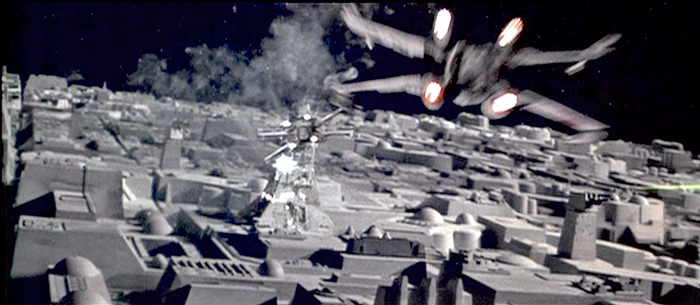

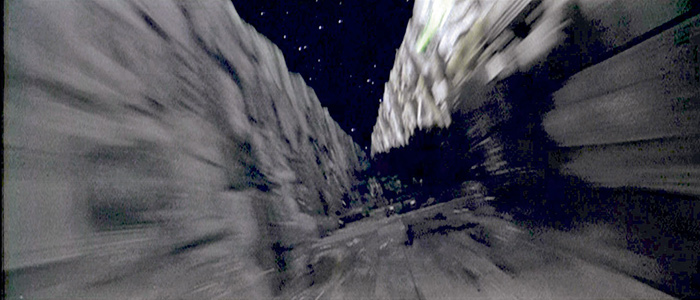

Lucas and his editors had started handing over pieces for the end battle sequence back in the middle of December 1976, but the complexity and quantity of the shots meant that ILM didn’t finish this part of the film until the middle of April 1977. Many shots were photographed more than once, and nearly all were altered to some extent. Before each was begun, Joe Johnston would do a storyboard for it. “George would decide he’d want a board changed here and there, so we’d go through the sequence,” Johnston says. “He’d pick out a shot or even pick out a frame and say, ‘Move the ship forty-two degrees this way,’ and that’s how most of the boards were done. He was real complete about everything, every little angle of every ship. He knew exactly how he wanted it. It’s really amazing.”

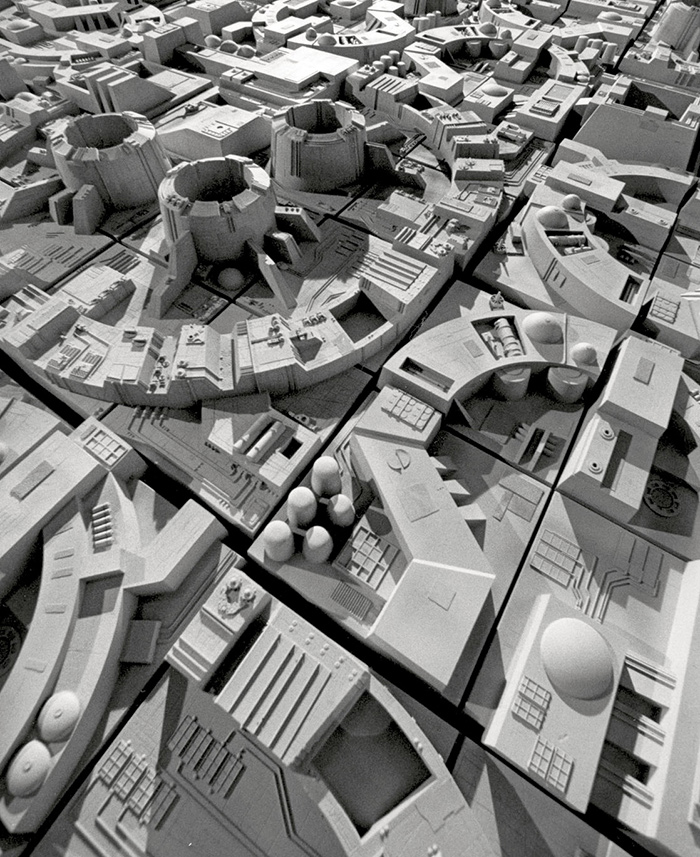

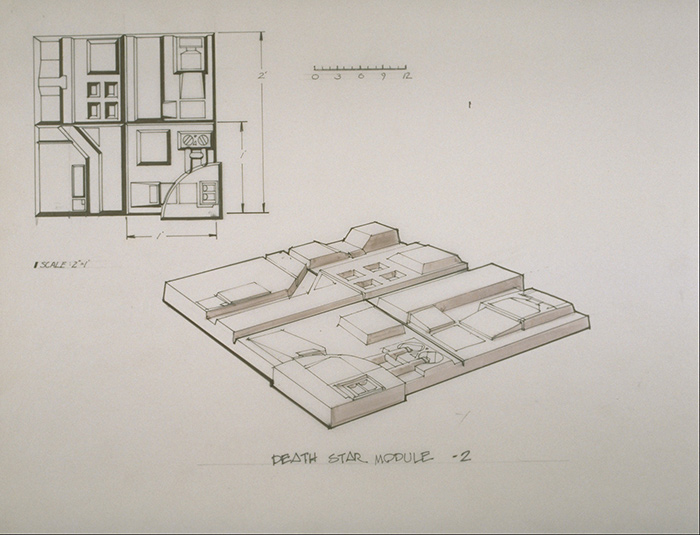

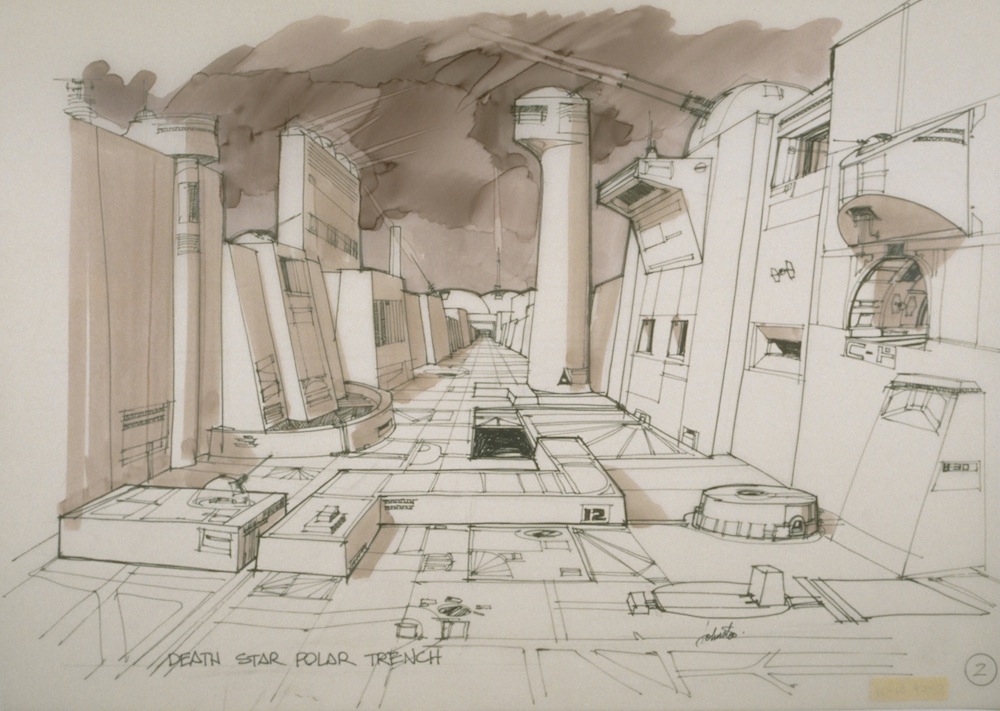

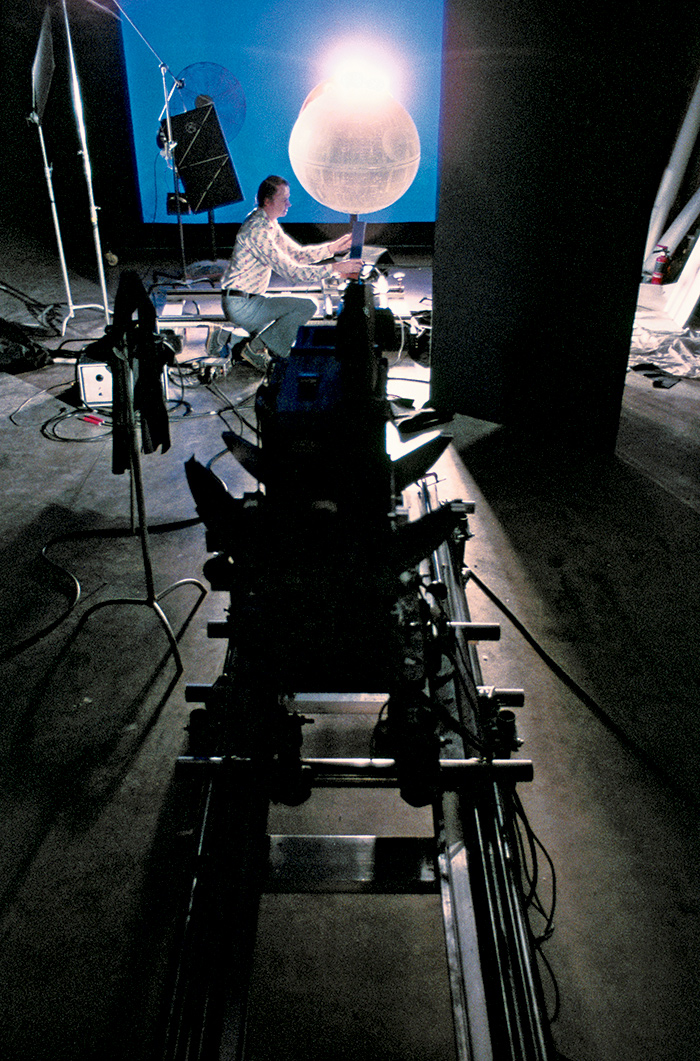

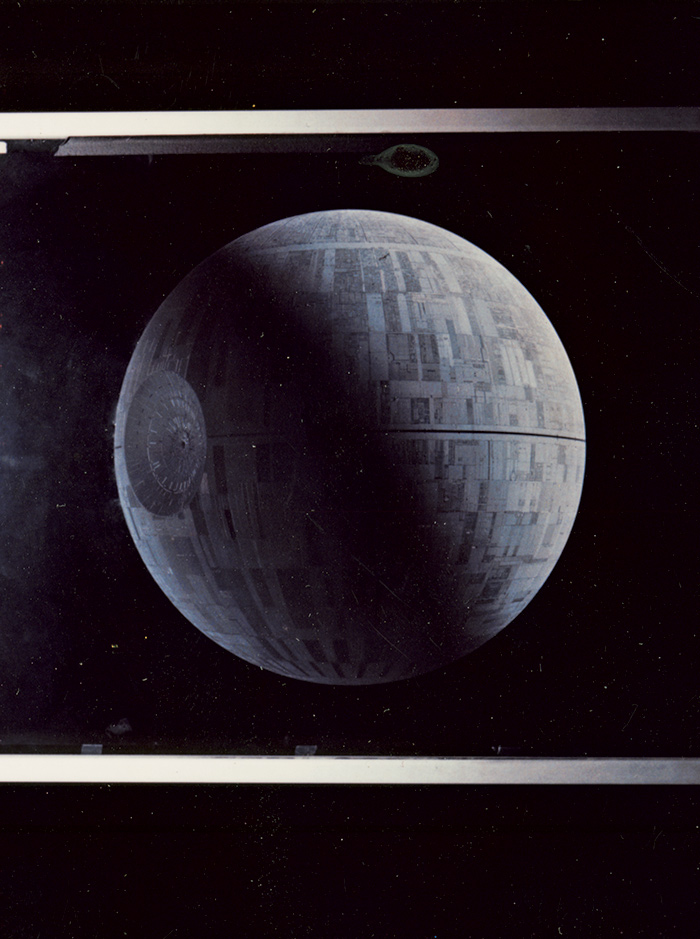

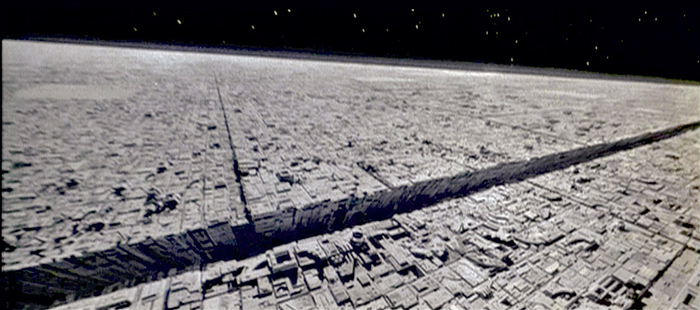

Of course, the object of all these intricately maneuvering ships was to obliterate the Death Star. In real life, however, it was building up the Imperial fortress that monopolized much of ILM’s time. Back in 1975 Colin Cantwell had made a conceptual model; Ralph McQuarrie had also done two matte paintings. But as ILM delved into the shots themselves, it became clear that the variety of work demanded a variety of Death Stars. A shot could move in on the matte painting, straight-on, but as soon as the shot wanted to pan, then the surface perspective would have to change, and they couldn’t make the matte painting appear to rotate. Moreover, the battle was to take place above and then within the Death Star trench—two entirely different locations, miniature-wise. Also, the size of the Death Star increased exponentially early on. “The Death Star became a sphere of enormous proportions,” McQuarrie says, “when the guys at ILM decided that it had to have a flat surface in order to run their camera above it and then we calculated the size of the sphere that would have a flat horizon when you were standing on the surface.”

A “threshold scale” Death Star was used for low passes over the surface.

A “sub-miniature scale,” another Death Star surface, was made from photographs of all the little parts reproduced at 150-to-l and pasted on a big curved surface (Mark Hamill inspects this one, with Mary Lind wearing glasses next to him), which was used for even higher-altitude shots.

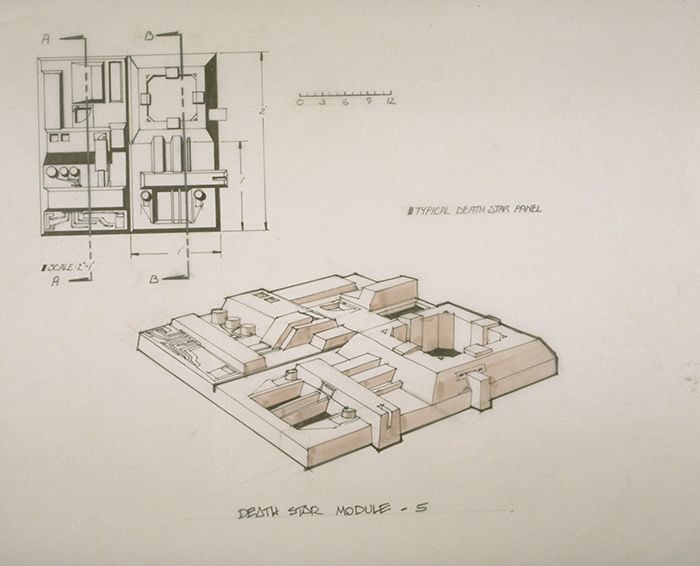

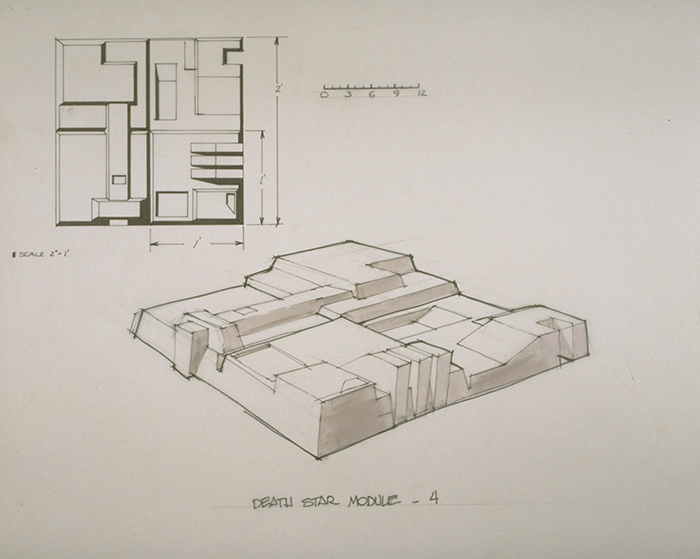

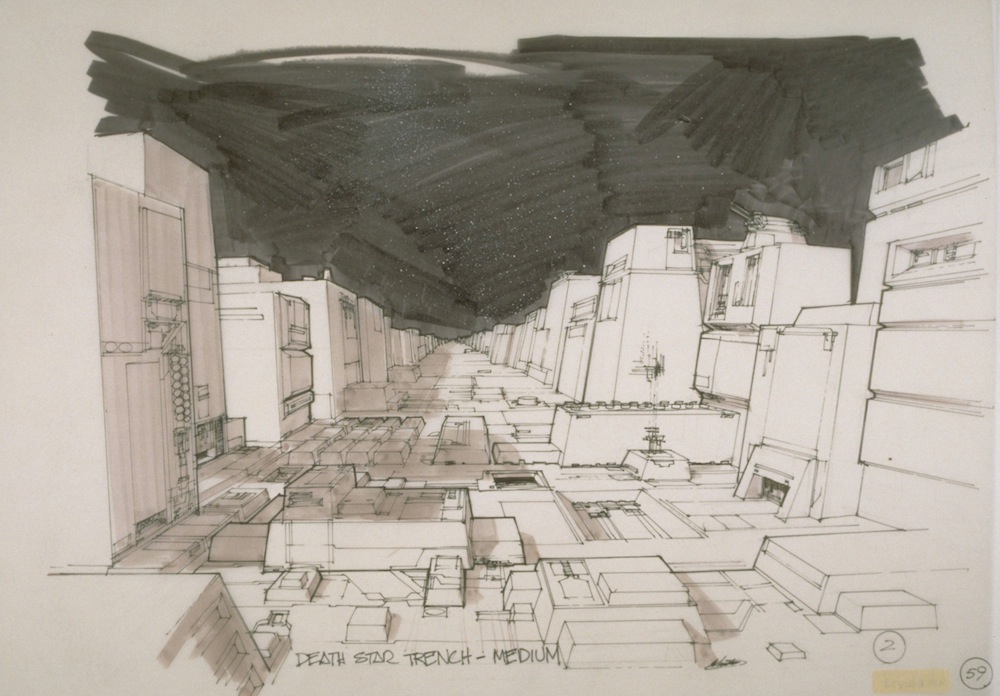

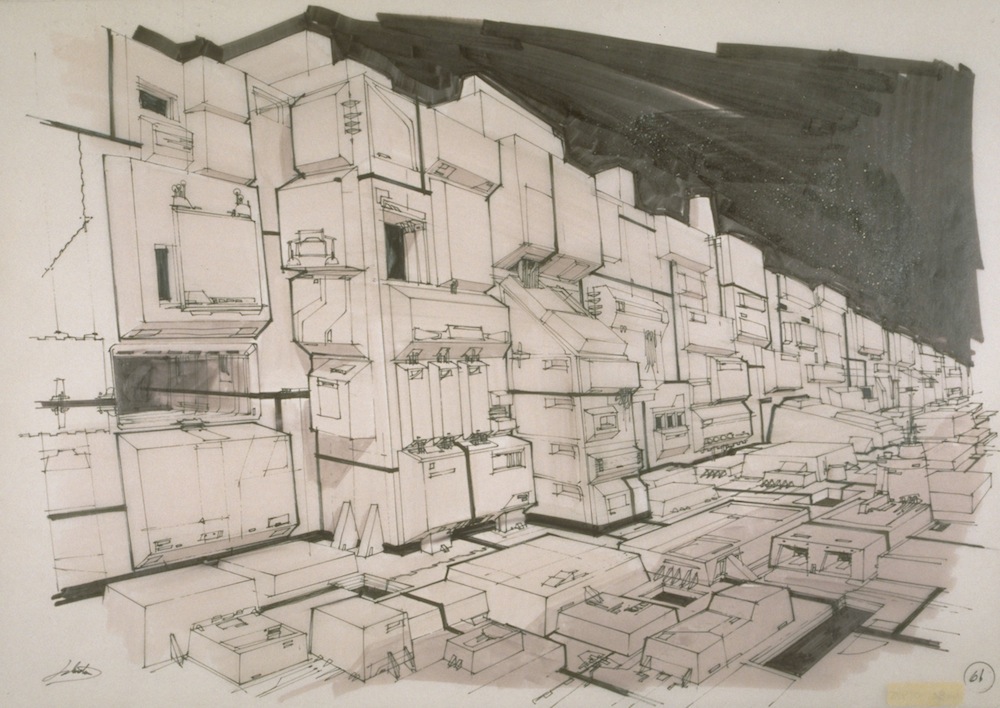

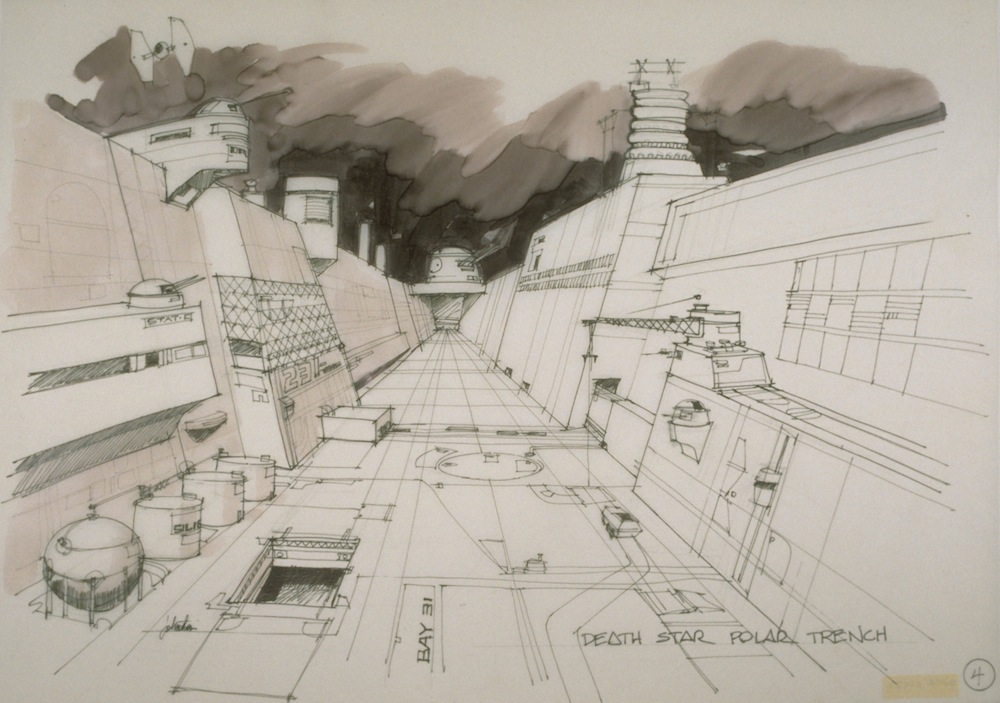

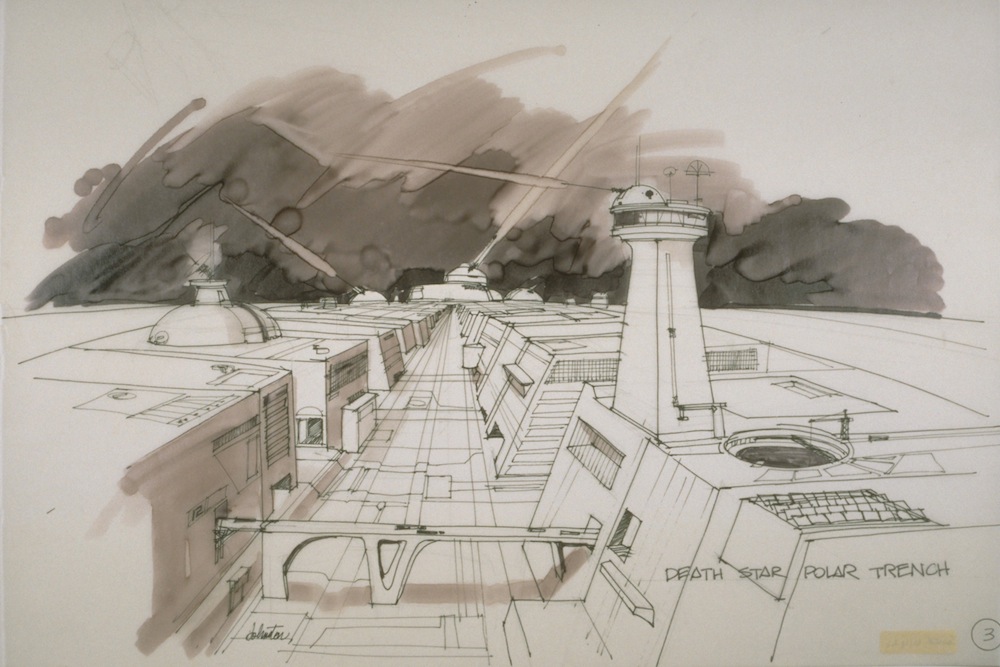

Much of the Death Star surface was made up of individually designed blocks or modules (see the concept art by Johnston below), which could be placed together to form a nearly endless variety of patterns. The battle itself was modeled on World War II dogfights and films.

Death Star module concept sketch by Joe Johnston.

Death Star module concept sketch by Joe Johnston.

Death Star module concept sketch by Joe Johnston.

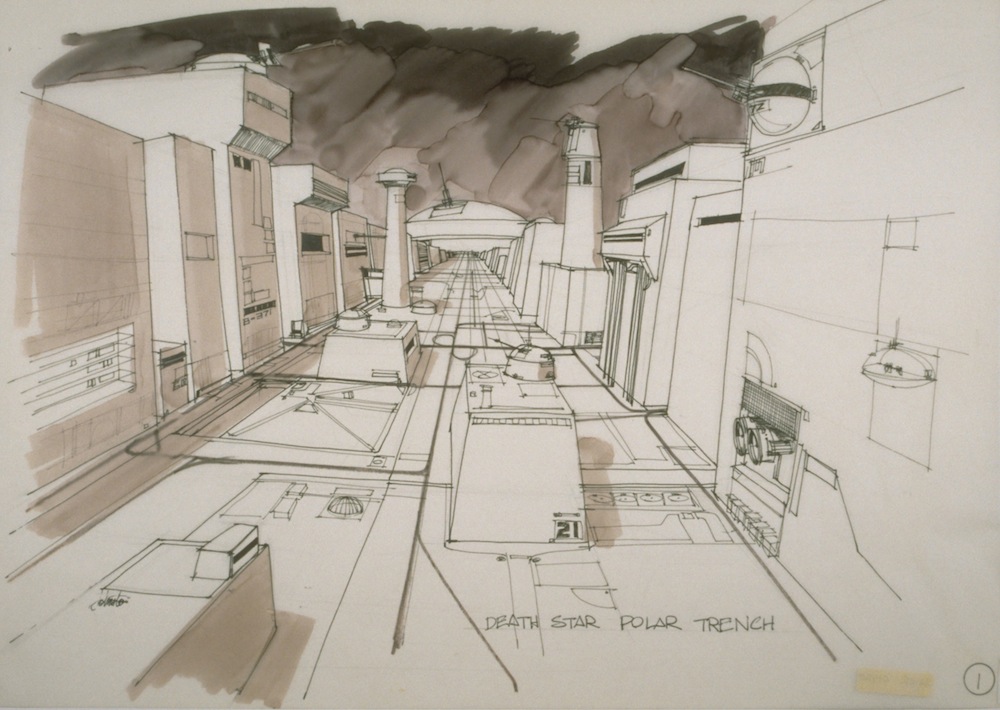

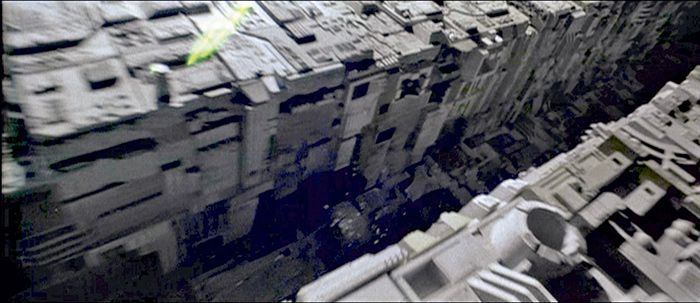

Initially the scale of the trench was dictated by the length needed and the length limitations. As they could move the Dykstraflex only forty feet at one go, and because the trench was supposed to be about forty miles long, the scale came down to a mile a foot. To fill those feet/miles, eight different modular units of three different-sized trench pieces were created; these could then be put together in an almost limitless number of combinations. For the surface of the Death Star a similar technique was used, with six pieces. The cost was about $5 or $6 per square foot. It was so inexpensive because the company that mass-produced the modules wanted a film credit, so they gave ILM a discount; but in the end the manufacturer went bankrupt instead.

“There was disagreement in the beginning between Richard, John, and George about what size the trench should be and how the surfaces should be arranged within each other and how the shots could come out,” McCune says. “At one time it was three feet wide and three feet deep; then it was two feet deep and three feet wide. The first time we built it, it took us a month to arrange all the parts, the second time it took us two weeks, and the third time it took us about three hours—it was just boom, boom, boom! Finally there was about sixty running feet of trench, including the end piece where the target area was.

ILM also built two trenches (threshold scale), though the wider version was ultimately discarded in favor of the narrower one.

With the threshold scale trench on its side, Doug Smith helps prepare a shot of X-wings.

Richard Edlund, wearing the red helmet, is propelled down the track while shooting an explosion in another trench against greenscreen.

Another explosion is prepared by Joe Viskocil (on ladder above TIE fighter), with Edlund behind the camera.

Final frame.

The Death Star polar trench (not equatorial, as some assume) was also based on many Joe Johnston sketches.

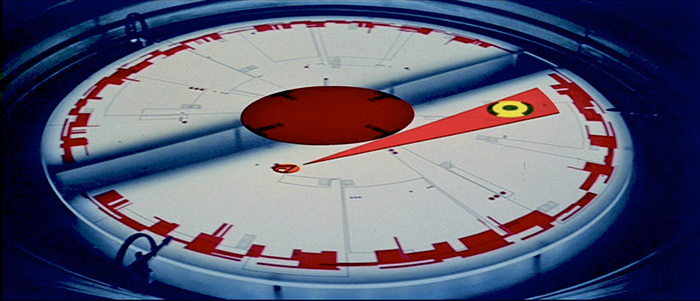

A model of the Death Star was used for some shots, which McQuarrie painted between November 12 and December 13, 1976.

He also did a matte painting of the Death Star, and specific parts of same.

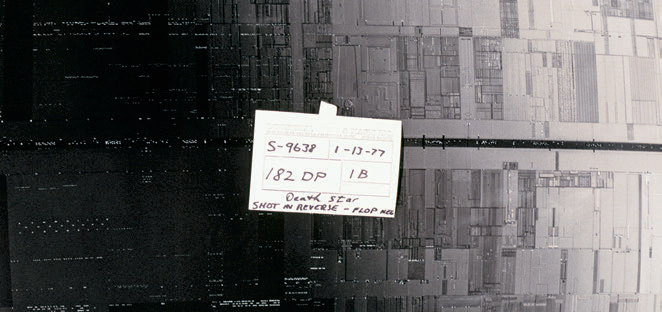

A piece of paper taped to one painting, completed in the spring of 1976, is dated January 13, 1977, for shot “182 DP,” which featured the fortress and three X-wings. That same day, according to ILM notes, the negative for “X-wing #1” went missing. “I had my first piece of negative disappear,” Mary Lind laments. “It didn’t get logged or something, shot 182, #1 X-wing. I looked high and low for three days, tore everything apart, could not find it, and finally asked the guys to reshoot it.”

On January 21, Muren reshot all three ships. On February 25, the Death Star color was toned down, because Lucas found it too blue. On March 18, notes reveal that one X-wing was still problematic, and Lucas considered going with only two—though ultimately all three appeared in the final shot.