As the May 25 release date drew close, and the last editorial adjustments were made, Paul Hirsch came to share Sam Shaw’s estimation of Lucas’s ability to keep on target. “George is the iron man,” the editor sums up. “He’s indefatigable. He just goes on and on, and I’ve got to hand it to him: The picture is an enormous accomplishment.”

While Hirsch, Gareth Wigan, Richard Chew, Steven Spielberg, and a growing number of insiders were feeling bullish about Star Wars’ chances, audience reaction was still a giant unknown. In any case Lucas and his closest collaborators were far too busy finishing the film to start prematurely congratulating themselves. One fear that actually disintegrated due to the mad dash at the end was the question of who would have final cut. Time became the ultimate arbitrator, because the final cut was simply not final until only weeks before it was due out in theaters, though, according to Lippincott, Ladd had agreed informally in early 1977 that no one at Fox would touch a single frame of the film.

“By the way, it was George’s idea to open the film in May,” Gareth Wigan says. “Nobody had ever opened a summer film before school was out. His idea was to open it on Memorial Day, that three-day weekend holiday.”

“The big weekend to open movies was Christmas, ever since movies began,” Lucas says. “The second time is the Fourth of July weekend. But I said I want my film to be released in May for Memorial Day weekend. And the studio said, ‘But the kids aren’t out of school’—and I said, ‘Well, I don’t want the kids out of school; I want the kids to be able to see the movie and then talk about it so we can build word of mouth.’ They thought I was out of my mind.”

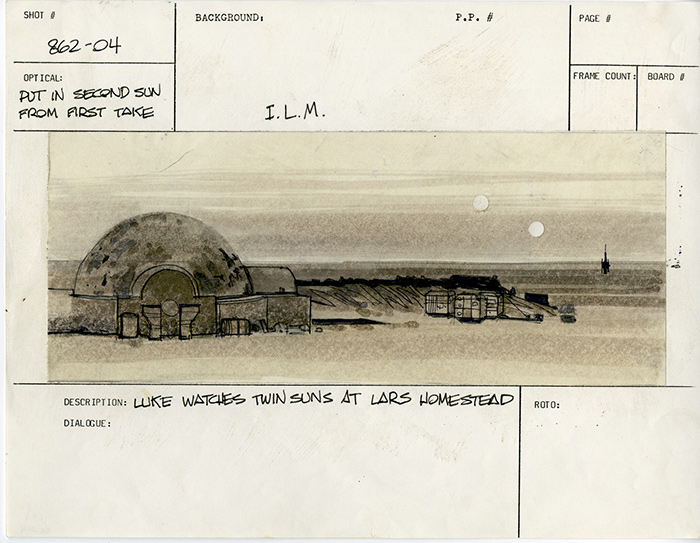

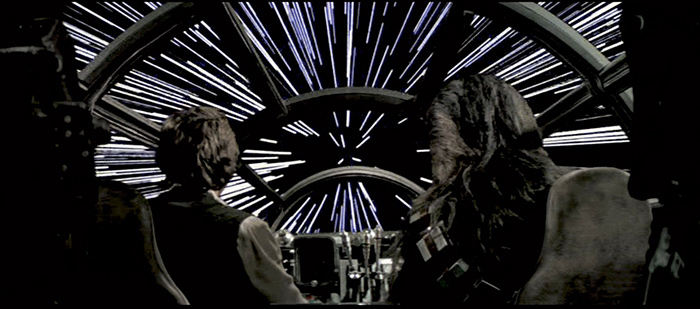

As of the end of April and the beginning of May 1977, ILM finished up its last photography. One of the shots, number 114, the jump to hyperspace, had been months in the works. Dennis Muren had begun the shot, creating the sense of great speed that Lucas had requested with a “streak thing” by keeping the shutter open and adjusting the start and end position of the camera to give a “punch” to it. Muren had left the production, however, by the time Lucas asked for the length of the shot to be changed, so Edlund completed it, adding the pirate ship to the second half of the shot.

“When the ship zips away into infinity,” he says, “the only way that I could get it that small that fast was to use a Polaroid shot of the ship with a zoomback on it.”

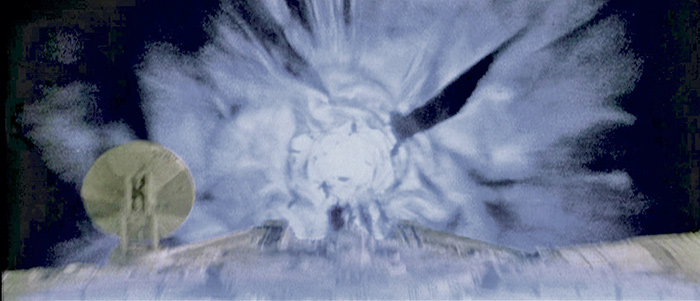

Another late effect was Luke’s blast that blows up the Death Star. “The last sketch that I worked on was the exhaust port model sketch,” Johnston says. “I think that was the last model built, too.” In fact, that model was a re-dress of the Death Star laser tunnel model.

The title sequence was also one of the last elements to be finalized. Following the critique and De Palma’s rewrite, Lucas had massaged it several times to coincide more exactly with the opening of the film:

It is a period of civil war. Rebel spaceships, striking from a hidden base, have won their first victory over the evil Galactic Empire.

During the battle, Rebel spies managed to steal secret plans to the Empire’s ultimate weapon, the DEATH STAR, an armored space station with enough power to destroy an entire planet.

Pursued by the Empire’s sinister agents, Princess Leia races home aboard her starship, custodian of the stolen plans that can save her people and restore freedom to the galaxy.

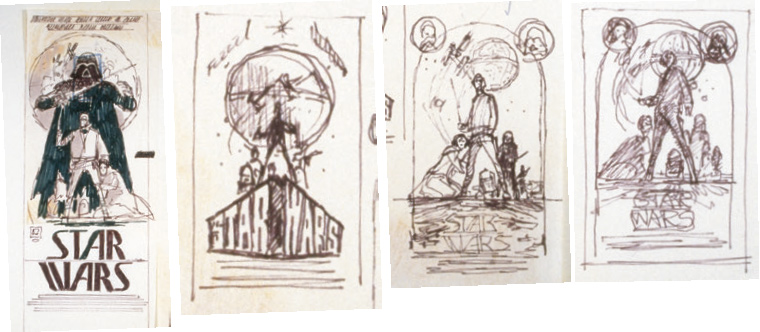

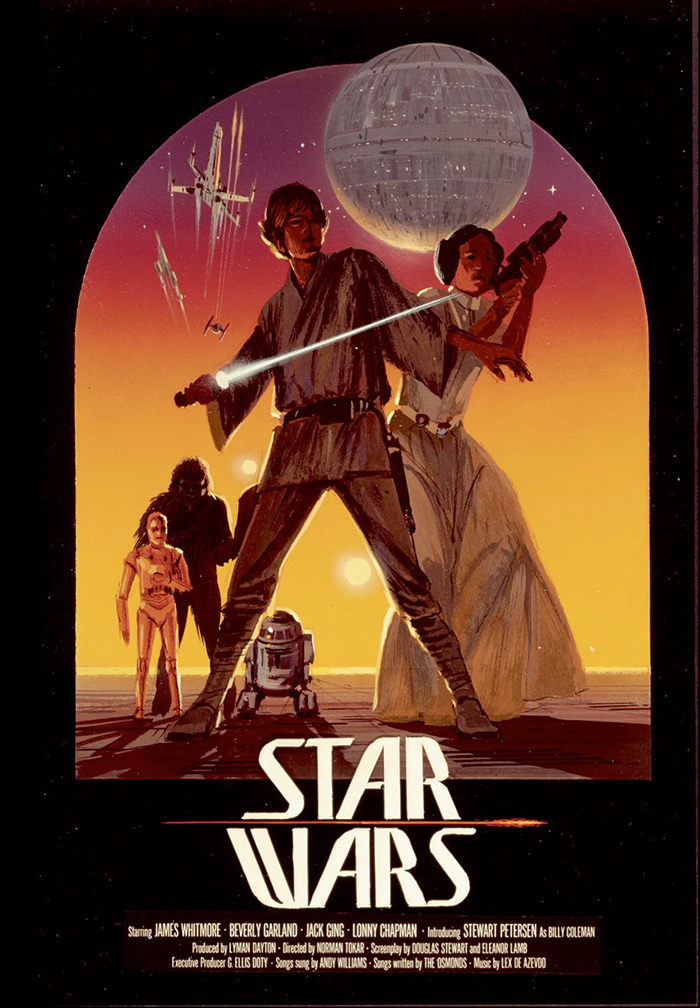

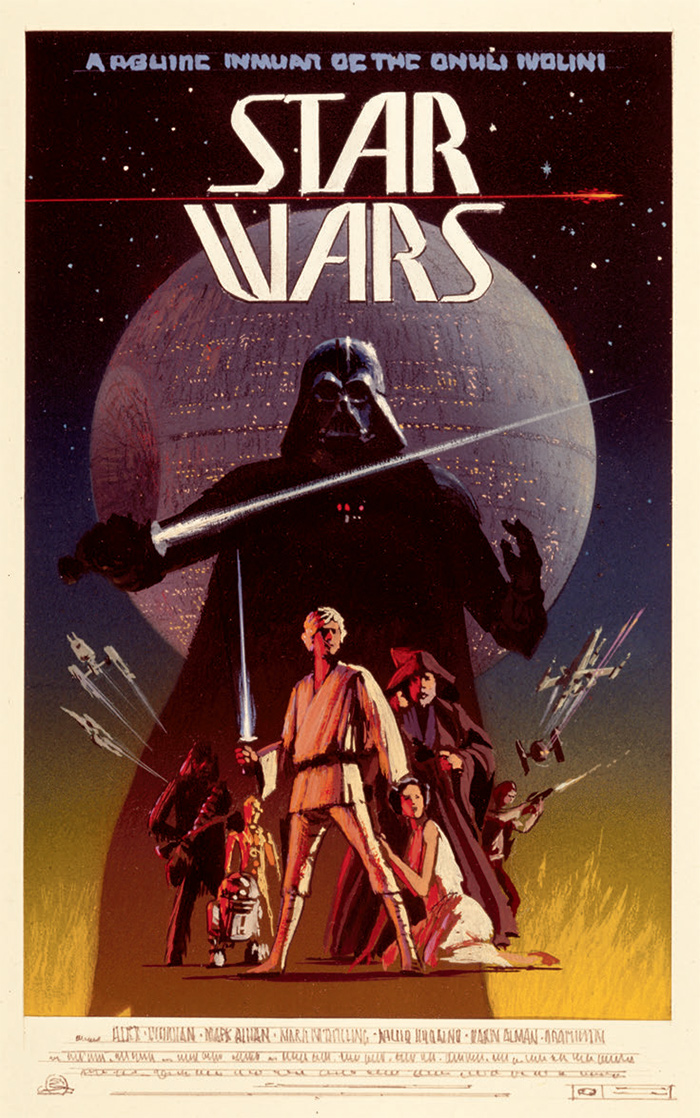

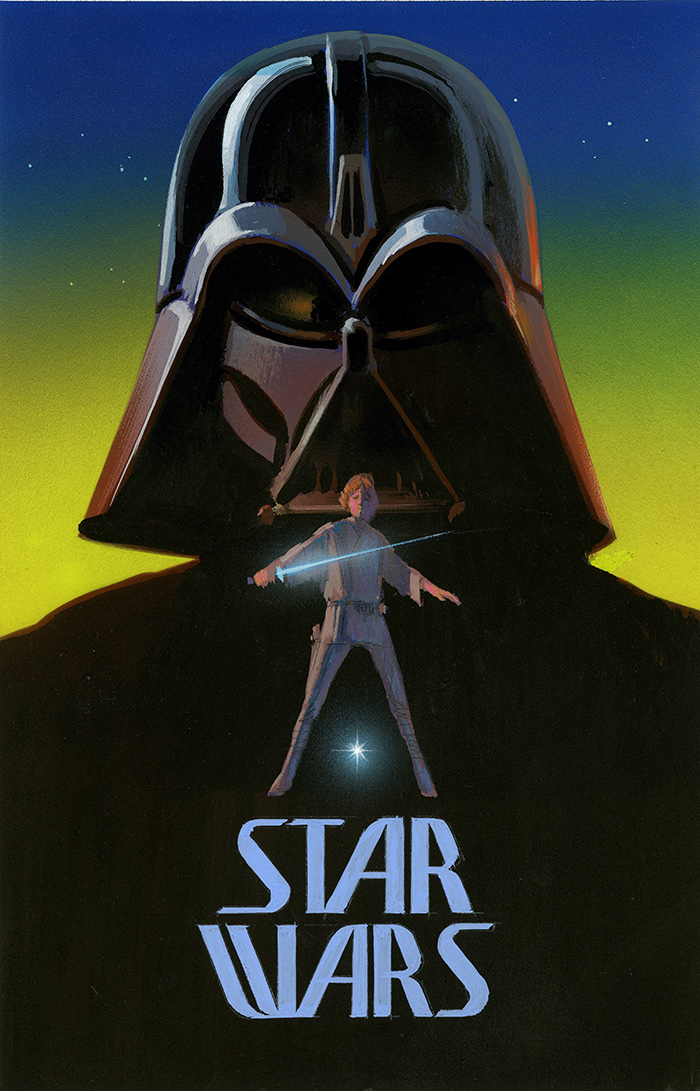

Ralph McQuarrie’s sketches led to his two concept artworks for the one-sheet poster, which he completed circa March 1977. Though neither concept was ultimately chosen, matte painter Harrison Ellenshaw says, “The greatest sales tool this film ever had was Ralph McQuarrie’s production paintings, in my mind.”

The Millennium Falcon makes the jump to hyper-space and eventually comes back to normal time in a shot that used “Mylar junk,” according to Lorne Peterson, for the eerie effect (below).

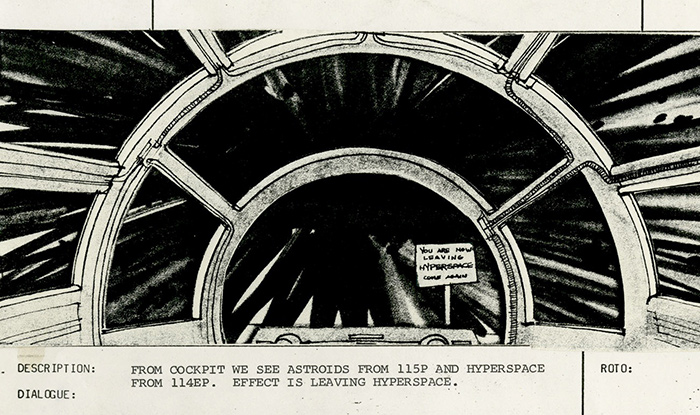

A story-board contains a humorous sign that reads, YOU ARE NOW LEAVING HYPERSPACE. COME AGAIN!.

Lucas had to insist on keeping the roll-up in the film, as Fox was pushing hard to replace it with a narrator who would read the words aloud. “I suppose there are kids that aren’t going to be able to read it,” Lucas says. “But they’re going to have to learn to read sooner or later. Maybe Star Wars will give them some incentive.”

“That was an interesting shot because it was one of the last ones we did, about three weeks before release,” Blalack says. “We worked with Richard, who created the perspective by using a tilting lens board and a wide angle, to get the correct exposure on his photography for the recedings, as STAR WARS gets smaller and smaller. The problem is that it gets very, very small, and the image begins to break up. It’s also being compressed through the anamorphic lens, so resolution problems are more severe. We shot it possibly six times to get the color, the fade-out on the logo, and all of that balanced out. It was the longest single shot that we ever dealt with.”

An eleventh-hour creature add-on was the Dia Noga head. In England they had filmed only the tentacle, but Lucas decided to give more personality to the trash masher occupant. “I got a call from Jim Nelson,” Phil Tippett says, “and he said, ‘We need another monster—it’s kind of an eyeball, with tentacles and things.’ I think that was the last thing we did.”

He and Jon Berg quickly sculpted, and Lucas approved, a creature whose eye could blink. They then went to the stage at ILM, where the model shop had created a miniature trash masher pond with debris floating in it, leftovers from the Death Star and exploded starfighters. “They cut a circle in the floor of the pond, which was up on sawhorses,” Berg recalls. “So I had to sit under there with the stuff leaking all over me, and just jam the puppet up through the thing, turn it around, and pull it back down.”

Yet another emergency was the point of view of the cantina exterior, which had yet to be completed—so the services of Ellenshaw were again required, but fast. “They never shot a good establishing point of view of the cantina,” he explains. “The only time they did, Alec Guinness and Mark Hamill were coming down the side, but of course it’s impossible to have their point of view with them in the shot. So they sent it to Van Der Veer to mask those people out. But George wasn’t happy with the result. So an assistant editor came rushing over one day, after I thought I’d finished with the film completely, with a piece of negative in his hand and said, ‘Here, George wants to know if you can paint out the people?’ This was a Tuesday, and he said, ‘Can you have it by Thursday?’ ‘I can have it about three months from Thursday,’ I said. ‘Thursday’s a little early.’ But he said they were actually cutting negative and they needed it to finish a reel!

Steve Gawley works on the exhaust port model.

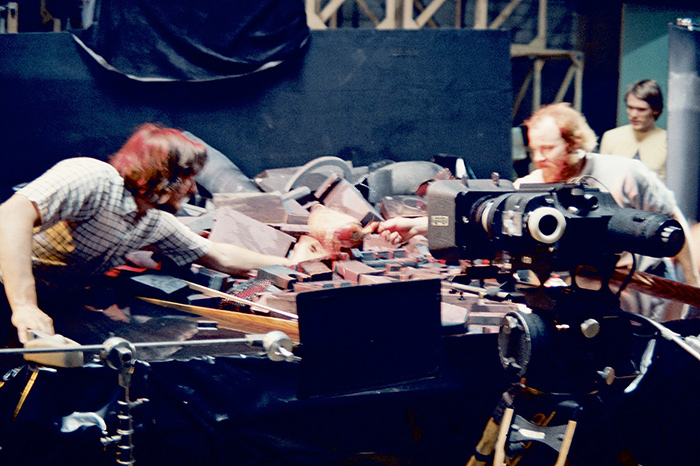

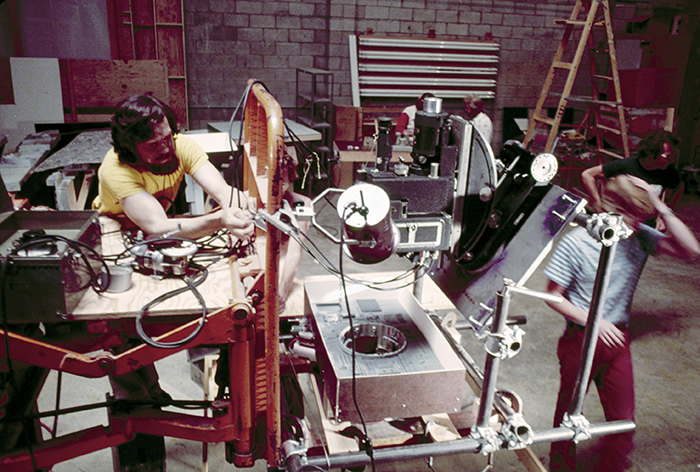

Berg, Tippett, and Johnston shooting the Dia Noga head.

“So I told him we could do it by a week from Thursday—and then we ran around like chickens without heads for a week and a half. It’s probably the fastest matte shot I’ve ever done in my life. You know, I think it was probably the last bit of film to go in the picture.”

Dolby Labs was founded by Ray Dolby in England in 1965, but he moved the company to the United States in 1976, right on time for its use in Star Wars. The Dolby system was designed to reduce unwanted background noise that, up until then, was almost unavoidably picked up during dubbing. The system also made dialogue easier to hear and enabled filmmakers, at least in theory, to create more complex sound designs.

“We chose Dolby right from the start,” Lucas says. “We looked at other systems like DBX, in terms of noise reduction, and realized that Dolby had the only really good stereo optical setup, and we really wanted to do the film in stereo. It was really the only option with systems that could be set up in theaters and worked right. It’s just a little box that they clipped onto the Nagra.”

The “only option,” Dolby was far from a sure thing. It was first used on A Clockwork Orange in 1971, but had achieved only middling success in the intervening years.

“I did have concerns,” Alan Ladd says, “only because we had already done a couple of pictures in Dolby. One was The Rocky Horror Picture Show, in 1975—it premiered in the UA Westwood Theater, and the Dolby fell apart on opening day. We also had a picture called Mr. Billion, which had just opened in March, which was done in Dolby. We took it down to Tucson to preview it—and it blew out the whole system. I mean, it was a mess. So there was a big concern about using Dolby. There was a lot of pressure from people saying, ‘Don’t use Dolby!’

The POV of the cantina exterior for which Ellenshaw painted out Luke and Ben.

“George wanted a shadow under the landspeeder. We were completely inundated, but Adam Beckett said, ‘I can do a shadow that will look real.’ But after Adam started to do the shadow, he could see the immensity of trying to generate a shadow where none existed,” Blalack says. “So I asked George to take that shot away from us; it was too much of a nightmare. It ended up going to Ellenshaw at Disney, and they struggled with it, so it ended up going to Van der Veer, and he finished it. Our prediction was that it would never work.”

Supervising sound editor Sam Shaw.

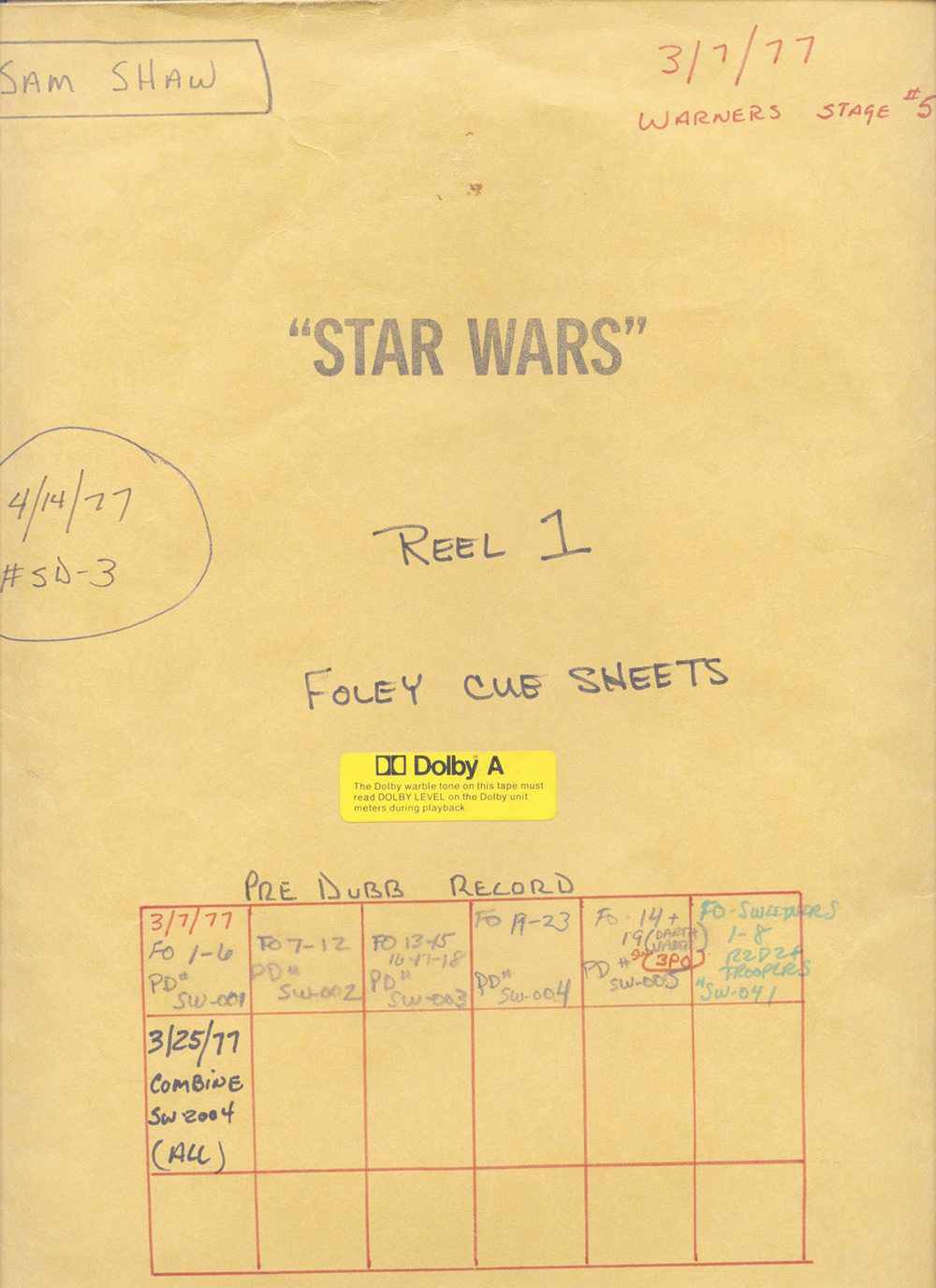

The cover of the file folder for the Star Wars Foley cue sheets, reel #1, with a prominent DOLBY sticker, along with March and April 1977 dates testifying to the last-minute work being done to complete Star Wars in time.

Foley workers in the studio.

“But the whole thing is that George knew how to use Dolby,” Ladd adds. “The other people, I think, were just using a process, and that was the difference. They just finished the picture, and then added Dolby. George, on the other hand, designed shots that would work specifically for the sound system, which is, I think, the first time that’s ever been done.”

“I was very satisfied with the Dolby system,” Burtt says. “We have much quieter tracks. The Dolby stereo sound consultant, Steve Katz, was a valuable influence on the mix, because of his technical knowledge.”

“Dolby didn’t create any problem at all,” Shaw says. “When you start dubbing something down, you get a lot of hiss. When you re-record any track, you get a lot of noise. The more you dub, the more background and surface noise you pick up. The Dolby’s main advantage is that it eliminates all that hiss. So for a picture like this in which there’s a lot of pre-dubbing, Dolby was excellent.”

The Dolby mix, however, was just the beginning of sound for Star Wars, as only parts of the English-speaking world were equipped for it. For crucial foreign markets and much of America, monaural and other stereo system soundtracks had to be prepared as well.

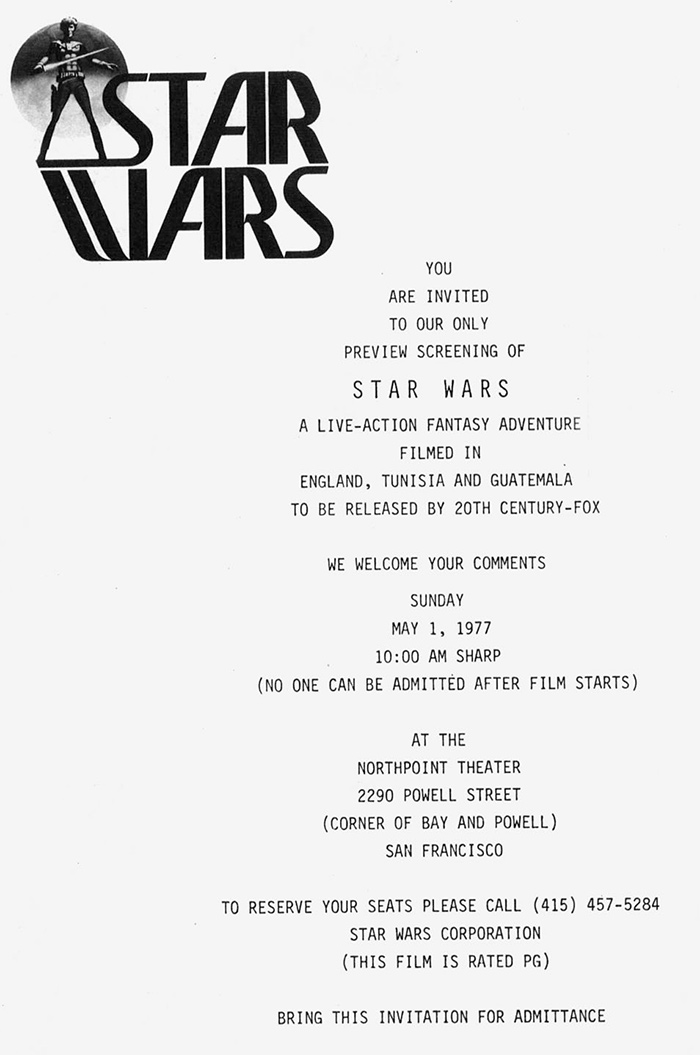

Although the film’s sound mix was not complete, Lucas decided to go ahead and preview Star Wars for the general public on May 1 at San Francisco’s Northpoint Theatre.

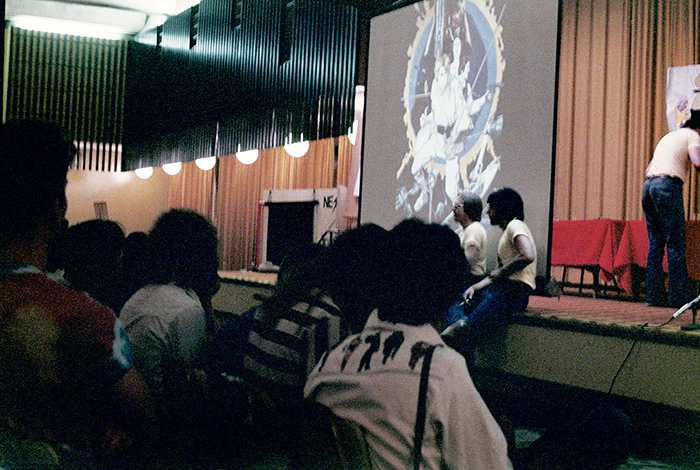

The lights went down as they always do, but the movie began in a way that no movie had ever begun before. The shot that Lucas and ILM had labored on for so long—his vision from so many years ago—unfolded as the seemingly endless Star Destroyer roared onto the silver screen and the eyes of the public. Accompanied by John Williams’s incredible score and Ben Burtt’s fantastic sound effects, the three-foot-long model created by teams of model makers and photographed by Richard Edlund succeeded in its intention: It made the Northpoint audience instantly and enthusiastically believe in the first modern fairy tale since the Western.

“May 1 was the best, was the strangest experience I have ever had,” Alan Ladd says. “I am not very prone to emotions, but when the picture opened up and all of a sudden they just started applauding, the tears started rolling out of my eyes. That has never happened to me. Then at the end of the picture, it kept going on, it wasn’t stopping—and I just never had experienced that kind of a reaction to any movie ever. Finally, when it was over, I had to get up and walk outside because of the tears.”

“They started rolling the movie,” Howie Hammerman says, “and when the Star Destroyer came over the top of the frame and kept rolling on and on and on, the audience just went nuts. They stood screamin’ and yellin’!”

The invitation to the May 1, 1977, preview screening at San Francisco’s Northpoint Theatre.

The regular show was the Paul Newman film Slap Shot, which had bowed on February 25 (the “uproarious lusty entertainment and world premiere” for “Alaska” could be a wink to Star Wars, as no film named Alaska came out in 1977).

Following the Northpoint preview, Lucasfilmers gathered round the table at Park Way to tally the written appreciations of the film (among those around the table are Charles Lippincott, Bunny Alsup, Ben Burtt, assistant film editor Colin Kitchens, Marcia Lucas, and film librarian Pamela Malouf).

Richard Chew was present that afternoon and was reeling afterward: “When I ran into George in the lobby, I expected him to really be exhilarated, and maybe he was, but certainly he didn’t show it. I was going to compliment him on the film—but the first thing he said was, ‘Well, as you can see things haven’t changed much since you last saw the picture, and we’re still trying to make it work.’ And it was like, ‘George! [laughs], man, you’ve got this wonderful movie I think a lot of people are going to want to see, and you’re so humble about the whole thing!’ And George’s father was around pumping hands saying, ‘Thank you, thank you very much for helping out George.’ [laughs] But George was being just old George!”

Although the May 1 preview was a huge success, it did cause Ladd some apprehension. He sensed that the younger kids were scared by the noise, and felt that they’d been right to ask for a PG rating. “It also moved very fast for most of them,” he says. “I sat behind a little girl and it moved too fast for her.”

“Fox was worried, Laddie was worried,” Lippincott says, “because several people had walked into the lobby, gray in the face.”

While Kurtz wasn’t sure if the rating would be PG back in January, Ladd’s comment reveals that the studio was favoring it. But Star Wars could have been rated G just as easily, for when the film was submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America’s Code and Rating Administration, the vote, as reported by Daily Variety, “was split evenly between G and PG.” In an unusual move, Twentieth Century-Fox “asked for a stricter rating.”

The reasons were two: Some scenes were arguably scary for children—but the studio was also concerned that there would be a “backlash effect from teenagers if the film were to receive a G, which is sometimes considered an ‘uncool’ rating.”

“I had a kid about five years old sitting in front of me,” Lippincott says. “And when Darth Vader appears on the bridge of the Princess’s ship at the beginning and grabs the guy and chokes him, the kid began crying, and just really broke down. So I said to George, ‘This film is a PG.’ Well, a friend of mine was on the rating board, and she was one of I think two females on the board, and she was one of the few who actually knew the film. She said the men were absolutely bored by it, a couple of them fell asleep, and they all voted it a G movie. The only one who was concerned about it was a mother, the only other woman there, who felt it was a little too intense for kids. But all the guys dismissed her, so it came out with a G rating—you know, the worst thing we could possibly get. I said, ‘This is not a G-rating film.’ So we went back to them for a PG. They had never had this done to them before by anybody, and they couldn’t believe it. So the board reneged and gave it a PG because we wanted that.”

After the general success of the Northpoint show, a second public screening was planned for the very next evening at the Metro Theatre— which added exponentially to Ladd’s concerns and justified Lucas’s hesitation to join the celebration. “People don’t know about the next night at the Metro,” Ladd explains. “I went there and there was not the same kind of reaction at all. I went to dinner afterward and I was so depressed; I was saying to a couple of people, ‘You should have been in San Francisco, you should have been in San Francisco …’ The next reaction I got was when we showed it at the board of directors meeting.”

The members sat down in comfortable gray chairs, Warren Hellman recalls, in a screening room on the Fox lot. “I remember the evening the directors were shown the finished film,” he says. “We walked outside afterward, and they handed us this little piece of paper that said, ‘Star Wars will 1) Be a breakout film, 2) Return our money, 3) Lose all of our money.’ Because I’m conservative, I was going to check the center column, but my wife, Christina, said, ‘Are you crazy?! This is the best movie I’ve ever seen! You’re going to make more money on this movie than you’ve ever dreamed of! Erase that!’ So I did and I checked the number in the first column.”

“There were sixteen board members,” Gareth Wigan says. “I remember clearly that three of them really loved it; three of them thought that maybe it would work, two of them fell asleep—they had just had a big dinner—and the rest of them really hated it. They really didn’t get it at all and were very distressed indeed, very worried about how they were going to get their money back.”

“Supposedly only two directors voted for ‘breakout.’ Most of them were neutral to negative,” Hellman adds. “We were all standing around outside and only Chris was saying, ‘This is great, this is fantastic!’ ”

“It played like a drama with the board of directors,” Ladd says. “I must say that there were more who didn’t like it than liked it. There was also a screening for radio and record people—and about ten people walked out …”

By the middle of May 1977, with the release date a mere ten days away, the final mix was still incomplete. The number of different facilities that had been used over the last few months make obvious the magnitude of the sound job, while hundreds of yellow legal-pad pages, tracking the minutest of details, attest to the intricate Foley—footsteps, kisses, shirt rumpling, scuffling, et cetera—recorded at Glen Glenn, on Stage A, during the month of March. Additional dialogue recording was completed in April at the Producers’ Sound Services, on North Highland Avenue in Hollywood, while much of the pre-dubbing was done at Burbank Studios. Dubbing was also done at Warner Bros., on Stage 5, and the final mixing at Goldwyn.

“The biggest problem of all was time,” Sam Shaw sighs. “Everything was just very specialized. There’s a thing called Foley in a picture, where you synchronize footsteps and all sorts of action. Everyone has done this dozens of times—but with Star Wars it was just mind-boggling! The amount that you would do for each reel was the equivalent to an entire normal feature film. It took special props, special microphones, tremendous adjustments. Professionals who had been doing things for twenty years would look at it and just be taken aback—they’d have to stop and psych themselves up. Normally you would have three mixers who would stay on the picture all the way through; we used about eight or nine mixers in the course of the show.”

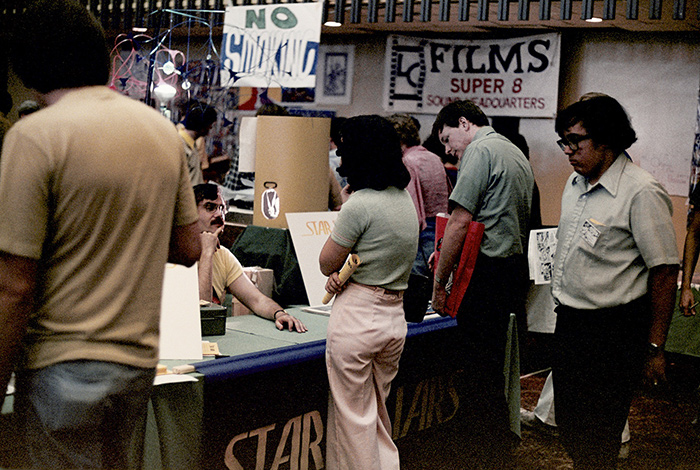

Kurtz, Lucas, and Lippincott examine publicity material.

The latter helped organize pre-release publicity at sci-fi and comic conventions.

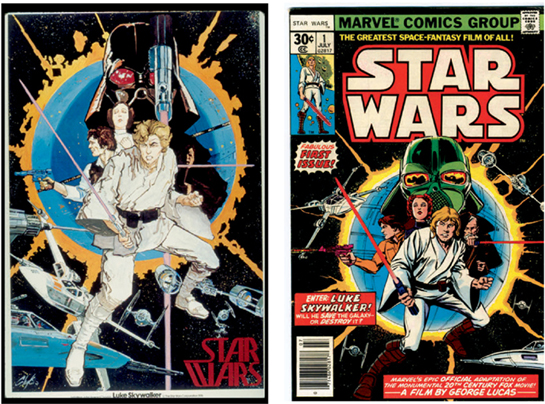

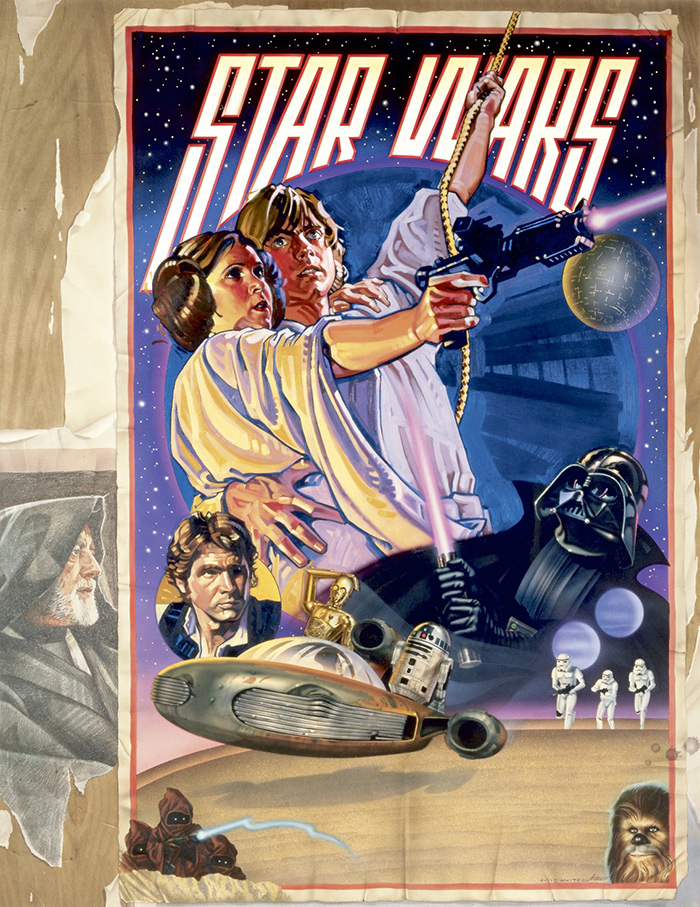

At sci-fi and comic conventions a poster by artist Howard Chaykin was shown and sold—which Chaykin later modified for the first Marvel Star Wars comic-book cover (which came out in March 1977, the first in a six-part series). Meanwhile, the novelization “was the fastest sellout of a first edition for a sci-fi movie novelization [Ballantine] had ever had,” Lippincott says, “which surprised the hell out of me—and them. It had sold out by February [after being published in December 1976, edited by Judy Lynn].”

“It was the blending of the sounds that was the biggest source of frustration,” Burtt says. “We had to depend on Sam Shaw’s people—and though the mixers did a tremendous job, they weren’t the filmmakers that had been on it for a couple of years and it was difficult for them to totally understand what we wanted.

“But George has a good attitude,” he adds. “Not being the sound editor himself, he has the advantage of looking at the whole thing and saying, ‘I want a blend between dialogue, music, and effects that gives me the story.’ We thought the sound was about 30 percent successful in view of what we intended to have.”

The first mix sent out with the film, at the last possible second, was the six-track Dolby stereo version, but the first mix also had the most errors. Next up was the two-track stereo, which was derived from the six-track, yet there was still no time at that stage to make any changes. “I asked Steve Katz to do something,” Burtt says, “but they were all too afraid to mess with it, ’cause the deadline was so close—the whole system with the Dolby was kind of an experiment, and they didn’t want me to tamper with it.”

A week before opening, there was still no answer print, but, by May 24, the thousands of elements and work-hours came together just in time—as Lucas says, the film wasn’t finished, it was “abandoned,” for time had finally run out.

Sitting in a Hamburger Hamlet on Hollywood Boulevard, Lucas noticed huge lines and limos across the street in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on May 25, 1977—and was surprised to see that Star Wars was the attraction (built in 1927, Grauman’s Chinese Theatre was called Mann’s Chinese from 1973 to 2001).

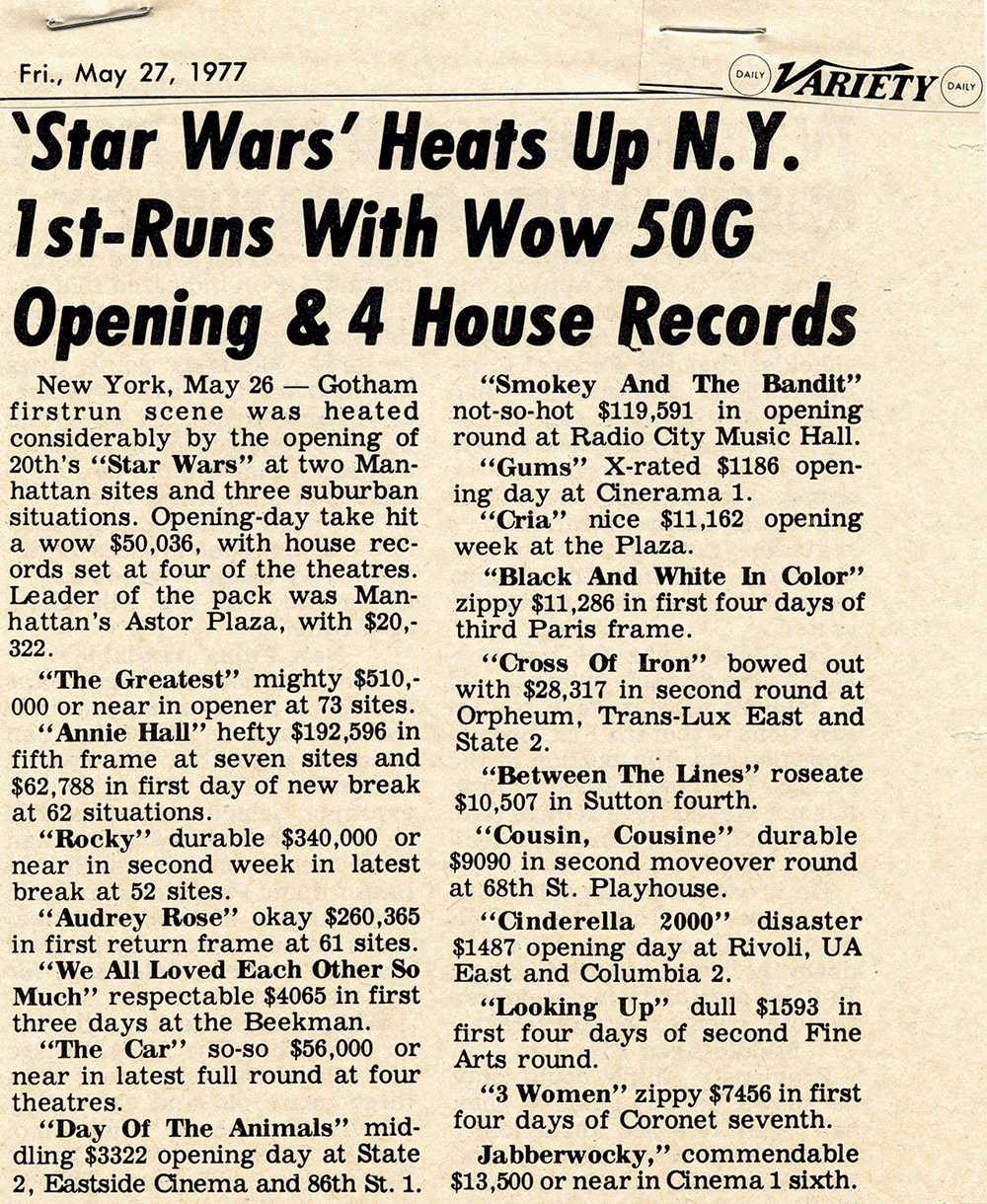

On Wednesday, May 25, 1977, Star Wars began its theatrical run, in thirty-two theaters, including the Coronet in San Francisco. On May 26 one theater was added, the Glenwood, in Kansas City, Kansas. On May 27 ten more theaters joined the ranks. In each of the less than fifty movie houses, the result was the same. Joy. At the Coronet the audience applauded as soon as the spaceships arrived—and the cheering never stopped, except at times to boo the villain, until halfway through the end credits. The landscape of cinema in the 1970s simply had no other film like it—and the world would never be the same.

Yet for Lucas, who was still working on the fourth final mix, the monaural, nothing had changed. “We’d finished the 70mm eight-track stereo mix, which Fox had resisted, and we were working on the monaural version for the wide release, so I was mixing at night,” he says. “I was approving ad campaigns, working all night and then sleeping all day in a little house that Marcia had on the flats of Hollywood. She was working on New York, New York. At the end of her day and at the beginning of my night we would have dinner somewhere—my breakfast, her dinner—and I think the night before we finished the monaural mix, it just so happened that we decided to eat at a Hamburger Hamlet on Hollywood Boulevard.

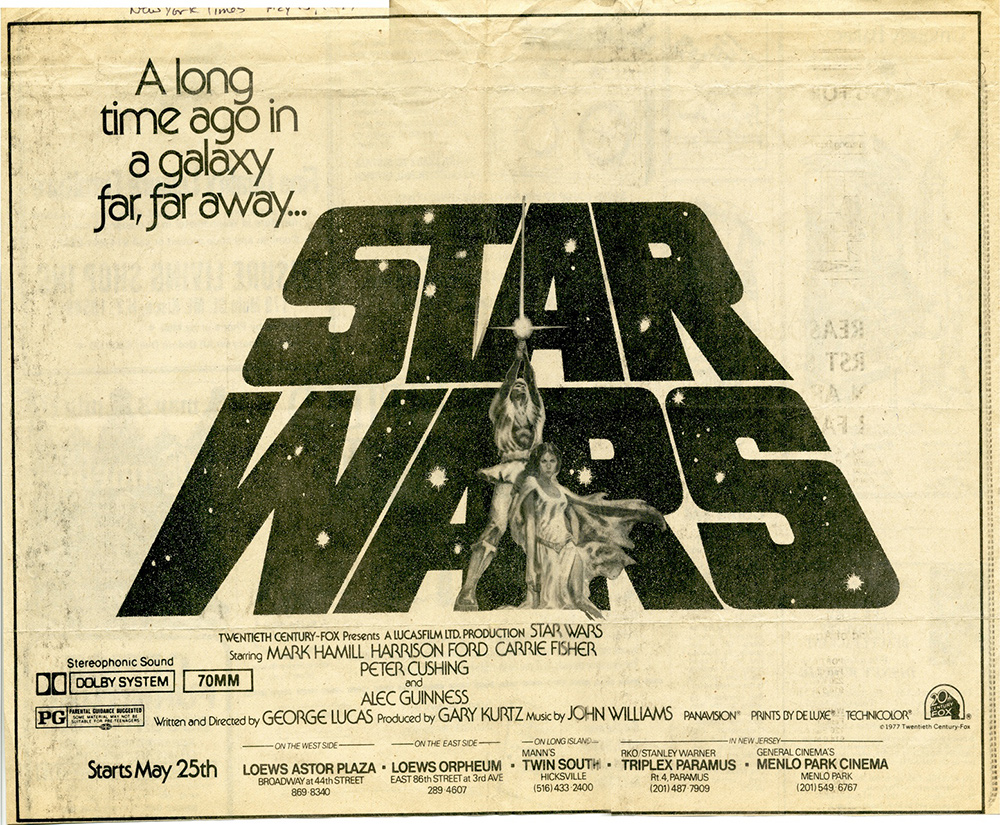

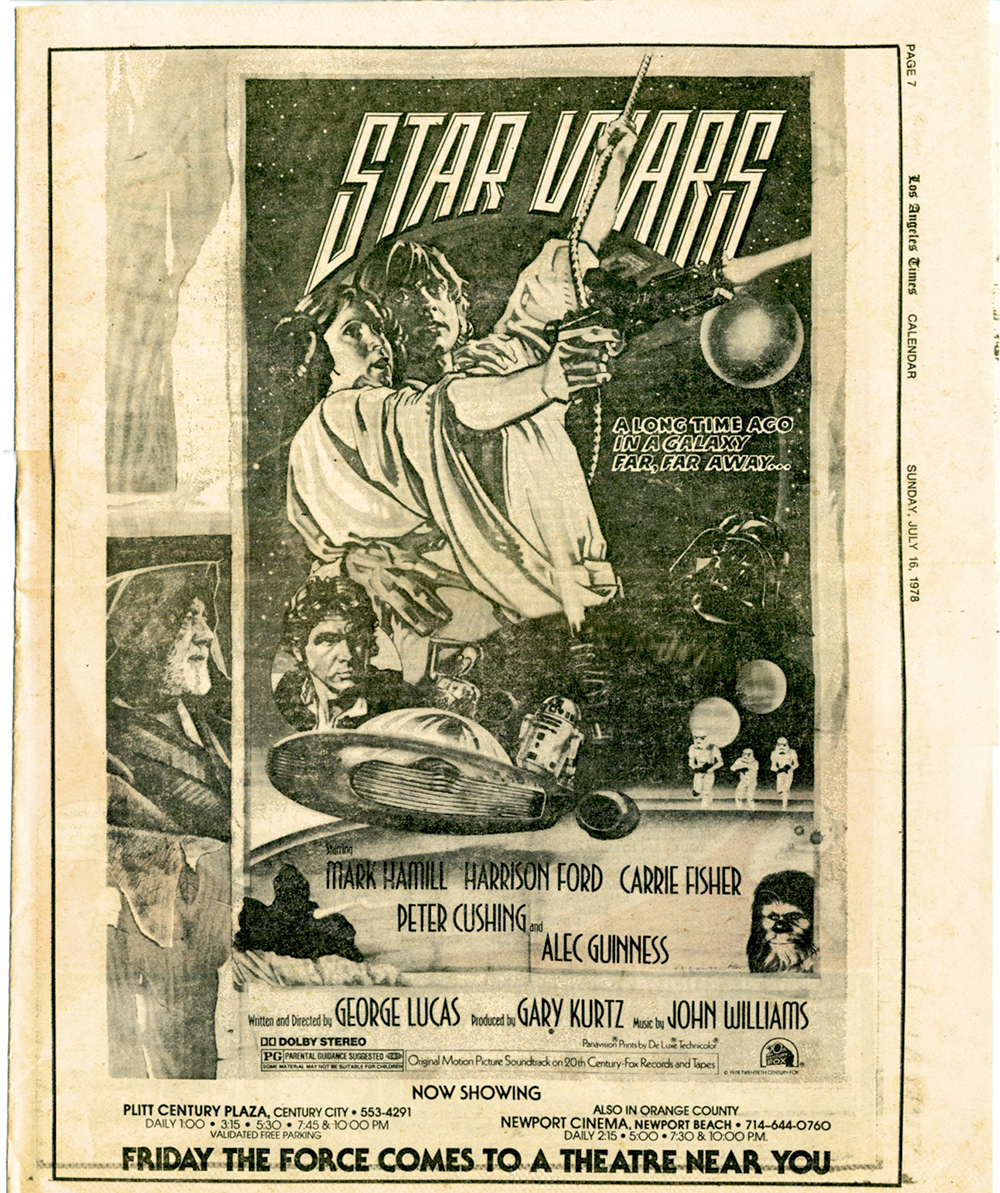

Star Wars posters took on several forms, one of which featured artwork by Tommy Jung.

Much of the artwork would then be modified for other media, such as the newspaper ad in The New York Times that ran on May 15, 1977.

“We were way in the back,” he continues, “but out of the front window I could see this huge crowd in front of Grauman’s Chinese—limos—and I thought someone must be premiering a movie. It never occurred to me that my movie was out, because I was still working on it. So we got up when we were done, and I said, ‘Let’s go see what’s going on out there.’ We walked out the door and I looked up at the marquee and said, ‘Oh my God, it’s Star Wars! I forgot the film was going to be released today! Holy moly!’ But it was like six o’clock, so I had to go back to the studio to finish the mix.”

Lucas must have been all the more surprised because Star Wars was never supposed to play the Grauman. It hadn’t become a prestige film overnight—it had simply benefited from the fact that William Friedkin’s Sorcerer, which should have been playing there on May 25, wasn’t finished (it bowed on June 24). Lucas’s film was the starlet waiting in the wings.

When the bemused director returned to Goldwyn, Gregg Kilday, a staff writer for the Los Angeles Times, joined him. Kilday was authoring a feature on Lucas and was able to observe events firsthand, including a phone call between Lucas and Alan Ladd, with the former muttering, “Wow … wow … gee … that’s pretty amazing,” as each box-office figure was read to him, interrupting Ladd only to offer instructions to the engineers.

“I called Laddie,” Lucas says, “and said, ‘Hey, I forgot the movie was going to be released today—how’s it doing? I was over at the Grauman’s Chinese and there were people around the block …’ And Laddie started exclaiming, ‘It’s a giant hit everywhere, we’re doing fabulous business!’ And I said, ‘Wait—calm down. Remember, science-fiction films do really great the first week, then they drop off to nothing. It’s a good sign, but it doesn’t mean anything. Let’s wait a couple of weeks.’ But he kept calling me all night giving me news.”

The call completed, Lucas still deflected the excitement that was fast becoming tangible in the studio. “I’m still going to hold my breath for a few weeks,” he vowed to Kilday. “The movie’s only been released for five hours. I don’t want to count my chickens before they hatch.”

Later that night, Lucas learned that the limousines in front of Grauman’s belonged to Playboy magazine founder Hugh Hefner and his entourage, all of whom ended up watching the film two times in a row. But none of this prevented him from continuing with the job on hand. “George, Paul Hirsch, and I and everyone in the crew sat down and made a list of the things we didn’t like in the stereo mix,” Burtt says. “Then we tried to achieve every one of those things on the mono. And we did— different voices for some of the stormtroopers, some new loop lines for Luke, minor changes.”

Star Wars made headlines repeatedly in newspapers throughout the latter half of 1977, including this Friday, May 27, article in Variety.

“We were locked in this little room, but it was important because monaural was what most people were going to hear,” Lucas says. In fact, he was so intent on finishing the list of fixes that he called up Mark Hamill that very night. Coincidentally, Hamill had also been stupefied by the lines in front of Grauman’s. “Imagine—the ultimate Hollywood theater,” he says. “I’m overwhelmed. It’s like having your career handed to you on a silver plate. But believe it or not, the night the picture opened, George called and said, ‘Hey, kid, do you want to come down and loop?’ I said, ‘What are you talking about? It’s playing. There are lines around the block!’ Then he explained that the print being shown was the 70mm stereo mix, and now for the monaural mix for general release, he wanted me to add a few things. Can you believe it? The day it opened …”

As the sound mixing continued without Hamill, who presumably looped on another night, Lucas explained himself to Kilday. “I expect it all to fall apart next week. I guess I am a pessimist, or a realist, a nonoptimist. I start out by expecting things to be the worst they can be, so when they’re better than that I’m not disappointed.”

One thing that was nagging at him was the ad campaigns. Marketing studies had been shown to Lucas claiming that women generally ignored the science-fiction genre, so he had been lobbying for, and now getting, a new promotional campaign designed to capture “female fancies,” according to Kilday. To that end Lucas conferred with an illustrator who was working on a new Gone with the Wind–style movie poster. Lucas was then interrupted by a series of visitors, including Marcia, who showed up with two bottles of champagne; Jay Cocks, who stopped by “for a few words”—and Brian De Palma, who congratulated Lucas and joked, “Shall we call Francis and spread the gloom?”

After they’d gone, Lucas turned back to quickly finish the interview, saying that Star Wars was a disappointment: “I expected more than any human being could possibly deliver. A Wookiee could have delivered it, but not a human being. I needed a crew of Wookiees. With nine hundred people, I was dependent on more people than I had ever depended on before. I had a tendency to agonize a lot over things not done as well as I hoped they could be done. I felt the same about Graffiti—then there was no time and no money. It was the same thing, only more so on Star Wars. There were a lot more people, a larger operation, but there was also more waste and confusion, bureaucratic screw-ups going on all over the place. Obviously, from everyone’s reaction, it was good enough—same as Graffiti. Pretty hard to believe, though, definitely beyond my capacity to understand.”

Kilday then departed and Lucas went on with his sound engineers, mixing until dawn.

Long lines formed for Star Wars in New York City, in front of Loews and the Orpheum, where it opened on May 25, 1977.

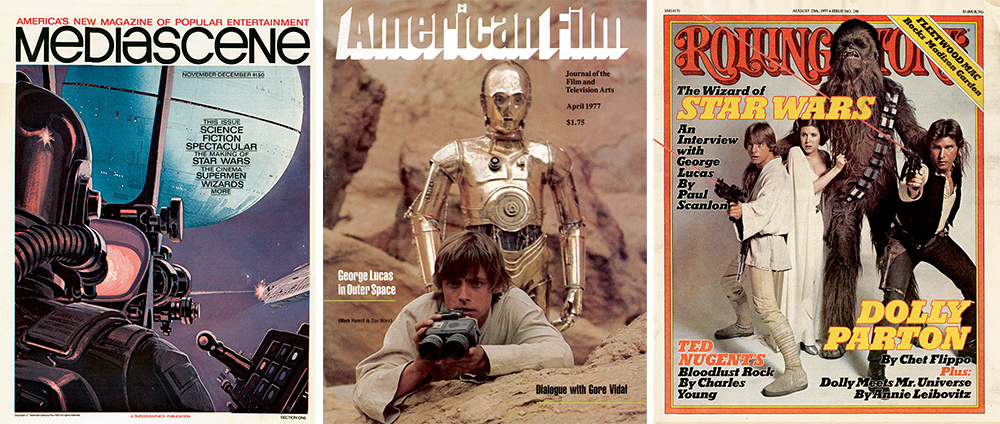

Early teaser material for the film had appeared in Jim Steranko’s November–December 1976 issue of Mediascene, with other audiences targeted in American Film (April 1977) and Rolling Stone (May 1977).

The lines that Lucas had observed in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre signaled the biggest opening day in its fifty-year history, with Star Wars taking in $19,358, according to Variety; at approximately $4 a ticket, that meant around 4,800 viewers (tickets at that time sold from $2.00 to $4.50, depending on the venue). The film also broke eight records in the other thirty-one theaters, combining for a grand single-day total of $254,809—one of the figures no doubt quoted by Ladd to Lucas over the phone.

“I worked on the mix that night, the next night, and then I left for Hawaii. I was done,” Lucas says. “There wasn’t much publicity to do. Fox had done something for all the press two weeks before, but I hadn’t been able to do it because it was at night and I was still mixing (Gary might have gone). So I took off for Hawaii with Bill and Gloria Huyck, and Marcia. But even over there we saw Walter Cronkite on television talking about Star Wars and we said, ‘Well, this is pretty weird.’ I’d told Laddie I didn’t want to hear anything about it, but he couldn’t help himself, and he called me every three or four days, very excited. We got papers after about a week, just at the time Bill and Gloria left and Steven arrived.”

The suddenly effusive Ladd no doubt echoed the ongoing headlines in Variety: The six-day box office was $2.5 million; on June 2, $3 million. But the other story, which has become legend in the movie world, took place on the beach where Spielberg and Lucas were building a sand castle and talking about future projects. Spielberg wanted to do a James Bond film, but Lucas said that he had “something better”: Indiana Jones.

“George got called away to the telephone to hear about the grosses of Friday and Saturday,” Spielberg says. “The 9:30 AM shows were sold out to a seat—that’s good when that happens. That’s a good signal.”

The papers also brought articles by nearly all the major reviewers. “Star Wars is a magnificent film,” “Murf” (Art Murphy) wrote in Variety. “The results equal the genius of Walt Disney, Willis O’Brien, and other justifiably famous practitioners of what Irwin Allen calls ‘movie magic’… Like a breath of fresh air, Star Wars sweeps away the cynicism that has in recent years obscured the concepts of valor, dedication, and honor.” Ron Pennington in The Hollywood Reporter predicted that Star Wars “will be thrilling audiences of all ages for a long time to come.” Gene Siskel gave it a good review in the Chicago Tribune, while Charles Champlin wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Star Wars is a celebration which, in the ultimate tribute to the past, has a robust and free-wheeling life of its own, needing no powers of recollection to be fully appreciated…Star Wars is Buck Rogers with a doctoral degree but not a trace of neuroticism or cynicism, a slam-bang, rip-roaring gallop through a distantly future world full of exotic vocabularies, creatures, and customs, existing cheek by cowl with the boy and girl next door.”

Nearly all the reviewers understood that Lucas had re-imagined the serials along with the swashbuckling and monster films of his youth. The film’s special effects received much notice, the actors not as much, though all were singled out for praise, especially Guinness. Several critics likened C-3PO to Edward Everett Horton, the comic sidekick in the Astaire/Rogers films of the 1930s, while R2-D2 was compared to Harpo Marx in Gary Arnold’s glowing Washington Post appraisal. “Lucas’s film is jaunty rather than portentous. One of the reasons [John] Barry’s cantina seems charged with humor is that Lucas doesn’t linger over it, as Kubrick lingered over the décor of the nightclub in Clockwork Orange. New perspectives and monsters keep turning up and moving on with astonishing and amusing rapidity. Lucas’s style of sci-fi prodigality is playfully funny.”

One day after the opening, Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote: “Star Wars is both an apotheosis of Flash Gordon serials and a witty critique that makes associations with a variety of literature that is nothing if not eclectic: Quo Vadis?, Buck Rogers, Ivanhoe, Superman, The Wizard of Oz, the Gospel According to Saint Matthew, the legend of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table.” Time magazine called it “The Year’s Best Movie,” and Newsweek was positive: “The army of credits for this serious and delightful labor implies a creative community that stands for the benign side of technology.”

Dozens of other reviewers were also won over by the film, in papers throughout the county—in Santa Ana and Sacramento, California; Salt Lake City, Utah; Evansville, Indiana; Camden, New Jersey; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Louisville, Kentucky, to name a few.

Negative reviews ran in the papers of Augusta, Maine; Pascagoula, Mississippi; and Statesville, North Carolina. The Harvard Crimson didn’t like Star Wars, and John Simon panned it in New York magazine. Another Big Apple publication, The New Yorker, ran a favorable review, and then a negative review a few months later. Stanley Kauffmann wrote in the June 18 edition of New Republic, “This picture was made for those (particularly males) who carry a portable shrine within them of their adolescence, a chalice of a Self that was Better Then before the world’s affairs or—in any complex way—sex intruded.”

Star Wars was also accused of racism, as its immense popularity made it a target—this because it didn’t have any African American actors in it, with the exception of the “black”-robed villain Darth Vader, who, either conveniently or paradoxically, was voiced by a prominent black actor.

Another minor controversy the press got hold of was the rumor that Lucas had deliberately used Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935) for the throne room scene. “The truth of that particular situation is that I hadn’t seen it for about fifteen years,” Lucas says. “I had wanted to see it again because, early in the writing process, I was thinking of doing a scene with the Emperor on the Empire planet, and I wanted to do that like Triumph of the Will. But it unfortunately got published that I was going to try to see Triumph of the Will and use it in Star Wars; evidently somebody read that somewhere and then looked at the end of the movie and thought that looked just like Triumph of the Will. But the end of the movie is just what happens when you put a large military group together and give out an award.”

Ultimately, there was enough paranoia about a film becoming so popular so quickly that Vincent Canby seems to have felt obliged to defend his positive review of Star Wars (and Annie, the Broadway musical!) by writing a follow-up in the Sunday edition of the Times, in which he said, “This is not a film of the Non-Think Age.”

The June 22, 1977, issue of Variety reported that telephone operators in the Los Angeles area were being “avalanched by callers seeking the numbers of the Avco Cinema and Mann’s Chinese” for show times—about 100 calls an hour, more than any number for the last ten years. “Operators have been so inundated that they don’t have to look up numbers; they’ve got them on the tip of their tongues.” On June 29 Variety reported that Star Wars had accumulated $8,780,435, but had been knocked out of the number one spot by The Deep and Exorcist II—The Heretic. However, by July 27, now in 48 theatres, Star Wars had recaptured the pole position after eight weeks, raking in $18,220,716.

Films had been wildly popular before—Gone with the Wind, The Sound of Music, Rocky, Jaws—but somehow Star Wars was creating even more excitement. In fact, with very limited publicity, gigantic lines formed up in each new town, city, or suburb—fueled to a great degree by person-to-person communication.

“I enjoyed it and would recommend it to my friends,” says youngster Ronnie Reed of Oskaloosa, Iowa.

“I liked the monsters the best,” five-year-old Darren Pierce says. “It was worth staying up past my bedtime.”

On June 23, 1977, in Chico, California, 500 people had to return home because the film’s premier at the 900-seat El Rey Theatre was already sold out, thanks to a line that had started five hours before. “We’ve turned away people before, but never in numbers like this,” assistant theater manager Richard Gorman says. In some cities, opening nights created huge traffic jams in front of the movie houses, preventing people from parking, so tenacious would-be attendees hopped into cabs to get to the show.

“My brother came to see it and said it was a real good movie,” notes 11-year-old Monika Caldwell of Clarksville, Tennessee.

“I heard it was a good movie,” fourteen-year-old Dennis Moore says.

“They didn’t give us any money for advertising,” reports Harry Stenzhorn, theater manager of Central City Mall 4 in San Bernardino, California. “They didn’t have to. They’ve gotten tremendous public relations for this movie without even trying. People really like the good guy/bad guy thing, kind of like a Western.”

Star Wars was also attracting all ages and types, from five- to 90-year-olds, from high school and college students to sci-fi fans and professionals. Whereas usually it was the moms who would take their kids to the movies, it was observed in Saint Louis, Missouri, that many more fathers were suddenly accompanying their children to the cinema.

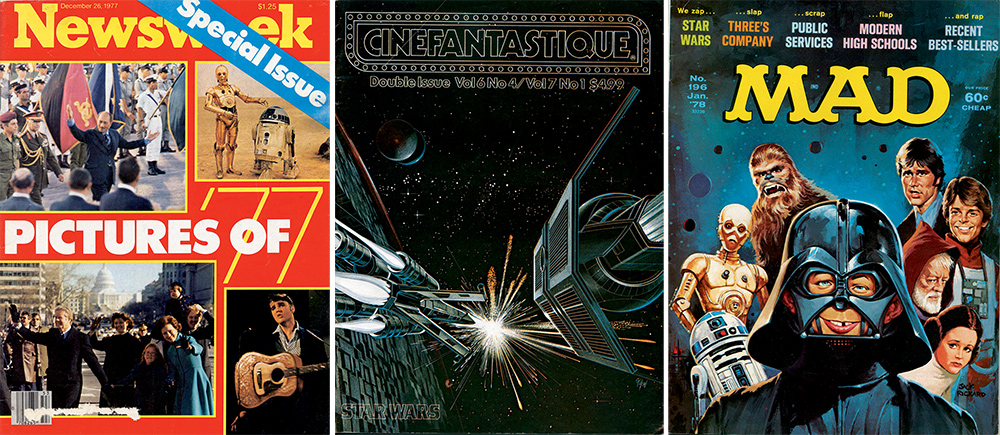

As the Star Wars phenomenon grew, the film made the covers of many magazines, including American Cinematographer (July 1977, where a unique, composited image shows Darth Vader’s ship actually being fired on by a Rebel X-wing), People (July 18, 1977), Famous Monsters (October 1977), Newsweek (December 26, 1977), Cinefantastique (1978), and Mad (January 1978). Shortly after the film’s release. Meco Monardo’s (45) disco version of the music became a Top 40 hit.

Audiences were lining up, new theaters were adding it to their marquees— and fellow film directors, both present and future, were impressed.

“When I saw Star Wars in its finished form,” Francis Ford Coppola says, “with all the effects in, and saw the complete tapestry George had done, it was very compelling and it was really a thrill for the audience. It all came together in terms of the characters and the story, the inspiration from Flash Gordon, with a little bit of Hidden Fortress. You know, all art, movies and otherwise, comes from something before that you are inspired by, which you borrow and make your own. That’s the artistic tradition.”

“I sent Stanley Kubrick a 35mm print and he ran it at his house,” Kurtz says. “It wasn’t in stereo or anything, but he said he liked the movie and he enjoyed it a lot. His children really enjoyed it.”

“I think that certainly everyone would agree that what has been so successful about Star Wars is the mythic dimension,” says John Korty, a Bay Area filmmaker and early inspiration for American Zoetrope. “This was somebody taking the grand myths of the past and recasting them in a form that made sense to modern-day people and especially kids.”

Another Bay Area stalwart, producer Saul Zaentz (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), took out a page in Variety’s June 6 issue; on Fantasy Film stationery, he wrote an open letter to “George Lucas and all who participated in the creation of Star Wars: You have given birth to a perfect film and the whole world will rejoice with you.”

“I came back into town just when the picture opened,” Carroll Ballard says. “I couldn’t believe it—there were lines around the block. I mean, it was the biggest thing that ever happened. I just couldn’t fathom it. But when I finally got in to see it, a transformation had taken place.”

“I had never experienced special effects that were so real,” says Spielberg. “I was dazzled. It was amazing—it was amazing and depressing at the same time. I was in postproduction on Close Encounters and I had just come back from Hawaii where I was with George, because I’d wanted to get away from that. But when I got back to the States I saw Star Wars and I thought my movie just paled in comparison. I was depressed for two weeks. I didn’t even want to release my movie in the same year as Star Wars. But Columbia was falling apart, and I had to cooperate, and we did great. But Star Wars was the star of 1977. George tapped into something very spiritual for young and old. Star Wars is a deeply spiritual story, yet somehow he made a war movie, too, and created a mythology of characters—he touched something that needed touching in everybody.”

A twist to the story is that while together in Hawaii, Lucas and Spielberg had swapped profit points on each other’s films—Star Wars and Close Encounters—because each was so sure that the other’s movie would make more money. “I’m very happy to say that I won the bet,” Spielberg adds with a smile.

Ridley Scott, who had just finished directing The Duellists, went to Grauman’s to see the film, and when he came out of the theater, “I basically said to my producer, ‘I don’t know what we’re doing—this guy’s making Star Wars? I’m not even in the same universe as this guy—I’m not even in the same century.’ ” His next two films were Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982).

Lucas’s space fantasy also inspired a new generation of filmmakers, who were either kids or just about to start in the business. “I got really energized by Star Wars,” says James Cameron, future director of The Terminator (1984) and Titanic (1997). “In fact, I quit my job as a truck driver and said, ‘Well, if I’m gonna do this, I better get going.’ ”

“Star Wars blew my socks off. It reinforced my love of movies and my desire to make movies,” says Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, 1994; The Green Mile, 1999).

“Going to Star Wars was one of the most exciting experiences that I ever had in my life,” says Peter Jackson, who would grow up to direct the Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001–2003). “Not just movies—in my life—at that time. It was the first time that I saw science fiction presented in a way where everything was beaten up and oily and greasy and grimy—and you just believed in it.”

“Anyone who knows me knows that my life was changed at that moment,” says John Singleton, who saw the film when he was nine years old, and who later directed Boyz N the Hood (1991) and Four Brothers (2005).

For Martin Scorsese, a longtime aficionado of cinema, the verdict was simple: “I saw it when it came out. It is what it is: the classic retelling of man’s mythology.”

For Peter Cushing, seeing the film with all the thousands of elements added was revelatory, if humbling. “I was absolutely knocked for six,”

he says. “I was riveted. There is an old saying among actors: ‘Never work with children or animals.’ Now we have to add to that, ‘or special effects.’ You swat away at your lines, trying to give a marvelous performance, and then a robot or a rocketship comes along, and the audience doesn’t look at you anymore. My only real disappointment was that poor old Tarkin was blown up at the end, which meant I couldn’t appear in any sequels.”

Cushing’s compatriot was similarly nonplussed. “I took my nine-year-old grandson to a trade screening,” Alec Guinness says. “He was a little scared and wanted to know if I was going to be killed. I wouldn’t tell him. The dialogue is pretty childish but the film has a lovely, fresh, innocent quality.

“My life is structured around making movies so I can do a play,” he added to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on September 25, 1977. “I don’t imagine things will change very much even now.”

The exact opposite was true for Harrison Ford, who, thanks to Star Wars, anticipated being able to stop doing carpentry and focus on his preferred career. “All of the characters I’ve played up until now have not been audience-identification type characters,” he says. “They have been plot devices that set up or explain something. And the more you fill that kind of part, the more you become a function of the plot and you don’t establish any kind of sympathy with the audience. It’s playing the kind of charm [of Han Solo] that wins people in casting offices. It’s certainly better career-wise to have done something that had an element of romance in it.

“I told George: ‘You can’t say that stuff. You can only type it.’ But I was wrong. It worked,” Ford adds.

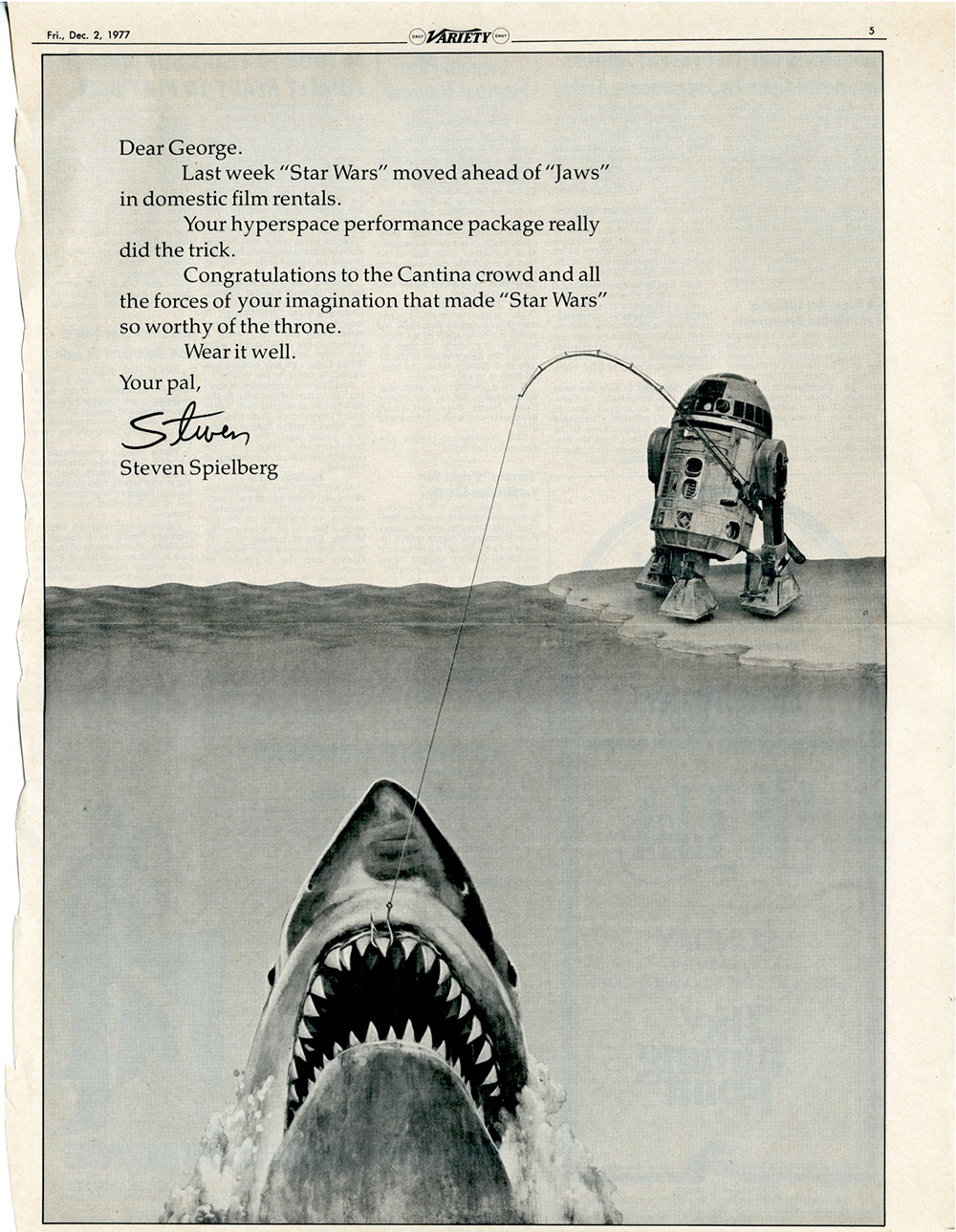

Spielberg took out an ad in Variety’s December 2, 1977, edition to congratulate his friend George Lucas on the fact that Star Wars had surpassed his own film. Jaws, at the box office—becoming the number one film of all time.

An internal memo at Lucasfilm, written by Debbie Fine, lists film-rental info accumulated by Fox.

“Star Wars got an amazing response,” Carrie Fisher says. “I used to drive by and look at the lines and think, What?! I haven’t had a chance to absorb the madness.”

“To this day [1978], people say to me, ‘God, I was really dumb: I didn’t realize how important this movie was…,’ ” casting director Dianne Crittenden says of the actors who auditioned back in 1975.

“We’re really surprised it’s doing so well,” Gary Kurtz told The Washington Star during a press trip to the capital in May 1977. “We knew there was a hard-core science-fiction-buff audience out there expecting it, but, frankly, we’re surprised at how big it has turned out to be.”

“I went to see it in a theater in a shopping center in my home town, and it was miserable,” Ben Burtt says. “The audience seemed to like it, but it sounded awful compared to what it could be. Weak and dead, like an old radio broadcast. I felt very sad for the people, for all the work that we put into it, because they couldn’t hear it as the film was intended to be heard.”

“There is really only one sort of movie magic, and it’s called directing,” John Barry says. “It’s very much like conjuring. A conjurer has his lady do something terribly interesting over here, while he gets a pigeon out of his back pocket. The jump to lightspeed is an example of conjuring, if you examine that scene very carefully. The film builds up to it—Han has to get the coordinates before they can make the jump—and it goes on quite a bit before you actually get the visual trick, which is a very short moment, but it’s great. George is very good at all that.”

“Star Wars is the first picture I really worked on that went to completion,” Ralph McQuarrie says. “So I didn’t really have that sense of what value the production illustrations were until I saw them on the screen.”

For Alan Ladd, who was elected to Fox’s board of directors in late July 1977, it was the end of many worries. The wild success of the film had proved Lucas right, to Ladd’s relief. “What nobody had understood was that George’s concept was to really just throw those things away, not dwell upon them, not ever give anybody the chance to say, My God, what a wonderful set,” Ladd says. “The whole thrust of the film was movement. That’s what he was going for. All of our concerns evaporated once we saw the final picture.”

“It was amazing,” Lucas’s assistant, Lucy Wilson, remembers. “You’d go to restaurants and people were sitting around you talking about the person you work for and the movie you were working on—and it’s on the cover of magazines. But we wondered, ‘Well, okay, this is huge—but in two years, you know, is there a future?’ ”

“We calculated, at the end of the project,” Robbie Blalack says, “that we had generated fourteen thousand pieces of film, given all of the separations, mattes, intermattes, garbage mattes, and lasers. All of those pieces of film had to be lined up by someone. All had to be printed by someone. The cataloging, sorting out, and the process of funneling that through was monstrous. The final count is 560 bluescreen shots compressed into 365 total shots, and it’s all one generation removed, except for six shots.”

On nearly all of those shots, the Dykstraflex camera was used—which amazingly had less than twenty-four hours of downtime due to mechanical or electronic failure for the whole production. Budget-wise, ILM spent $3,619,601, $2 million over the studio-imposed ceiling, $1 million over the original estimate. The revised final budget for outside optical effects came to $273,369.

Twentieth Century-Fox also took out an ad, in the September 16, 1977, edition of Variety, to trumpet Star Wars as the studio’s number one film of all time.

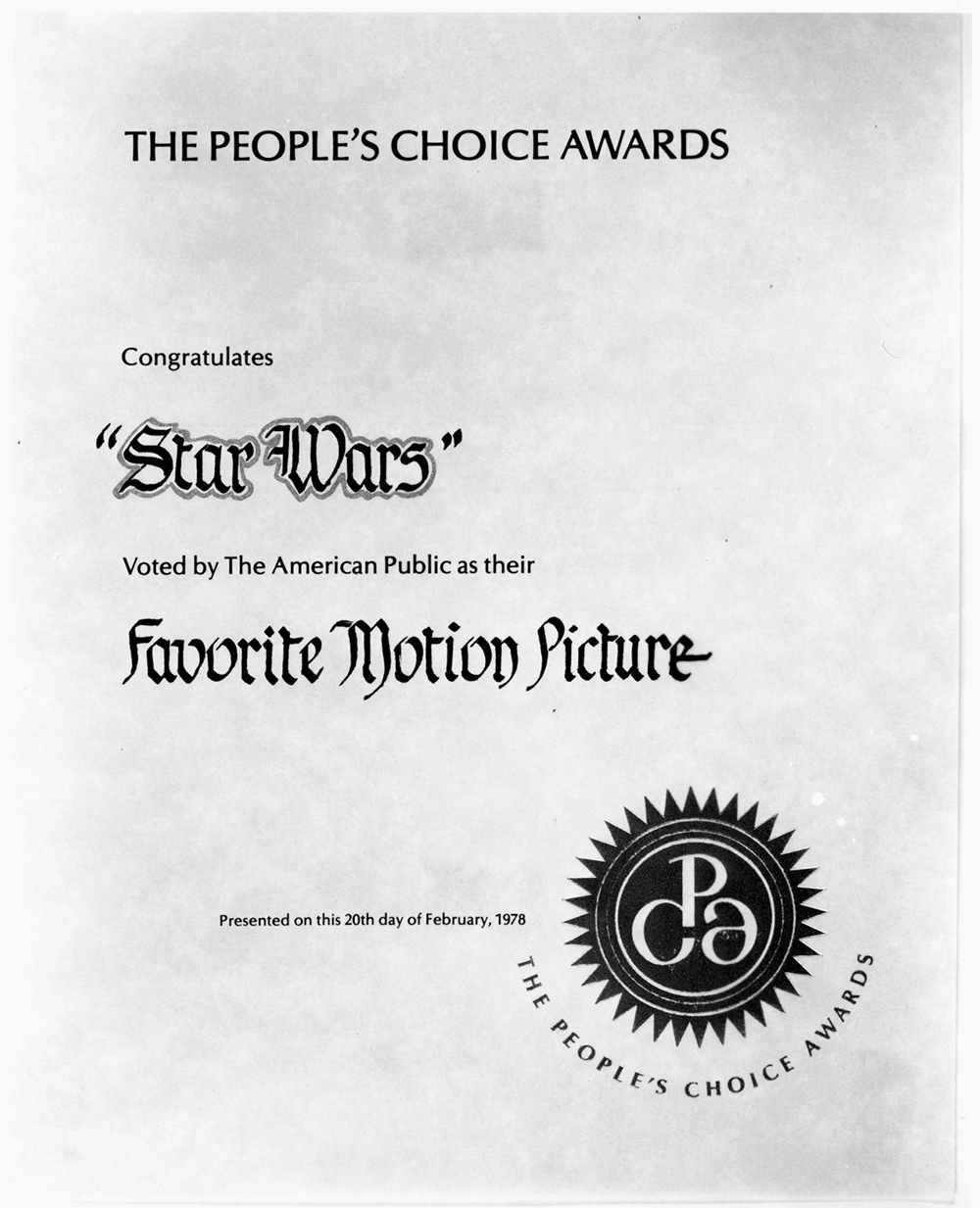

The People’s Choice Awards for Favorite Motion Picture of 1977 went to Star Wars in 1978.

“This was my first experience with real special effects,” Lucas says. “I had worked in opticals and animation before, but I hadn’t really worked on the kind of problem-solving special effects that were generated by Star Wars. I find it fascinating. I’d like to continue to work out some of the things and try to advance them—because I don’t think we took them as far as they can go.”

“I think it came out fabulously, considering the limitations of time and money,” Dykstra says. “It was a really unique group of people. And I really respect all of the stuff that George did to make it happen.”

“George said at one point, ‘I wore my favorite clothes, and never has so much money and time been spent on fun,’ ” Richard Edlund notes. “We certainly had a lot of fun doing the effects; it was fun to get up and go to work every morning.”

“It was always difficult for me to accept George’s idea of having the starfighters move at a tremendous speed and, of course seeing the film now, I agree with him completely,” says Dennis Muren.

“There’s a funny story,” Edlund adds. “Joe Johnston went to the DMV one time when Star Wars had just come out, and he was standing in a line that went back to the door, and someone came in, looked at the line, and said, ‘Shit, they ain’t playin’ Star Wars here, man!’ ”

“I remember leaving the theater and having these kids ask us for our autograph,” Joe Johnston says. “We said, ‘No, you don’t want our autograph, we’re like model builders.’ But they said, ‘No, no, we want you to sign this!’ So we were thinking, Wow, this must mean something—people are asking for our autographs!”

Fan interest was mirrored to some extent by crew interest, both just before and after the film came out, as its physical props became increasingly valuable. “Once people knew it was going to be a really good film, things just started disappearing,” Mary Lind recalls. “That’s when everybody put locks on the doors.”

As head of Film Control, Lind was also in charge of locating a secure and technologically safe resting place for the now incredibly precious negative. The optimum facility was found at the Hollywood Film Company in its vaults on Seward Street, with black-and-white optical elements stored in vaults 203 and 204, and negatives of the entire film in vault 356.

Her last duty fulfilled, Lind, who had come to work prepared to leave directly for Hawaii, jumped into a taxi and sped to the airport wearing a bathing suit and sandals.

“Fox went, in a very few years, from being a company right on the edge to being a very profitable company,” Warren Hellman says.

In short, the studio’s stock rose from a low of $6 a share in June 1976 to nearly $27 immediately following the release of Star Wars, according to Aubrey Solomon’s Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. On June 22, 1977, Variety pointed out that the volume of Fox stock traded, 7,808,400 shares since May 23, exceeded 100 percent of the firm’s common stock. A rumor circulated at the time saying that insider trading had taken place, given that a few individuals had bought up Fox shares right before Star Wars came out, while the stock was low, and then made millions when the stock soared.

“The story was that some people were sufficiently prescient to realize that there was this big hit coming and bought the stock while it was cheap,” Gareth Wigan explains. “But the truth is, there were very, very few people within Fox, and certainly none of them had any stock, who believed Star Wars was going to be a huge hit. I think in fact the reason the stock moved up is that a lot of people thought it was going to be a catastrophe and the studio was going to lose all its money, and therefore the management of the studio might easily change—and therefore this was a move to acquire stock with a view to a takeover. I think they were actually trying to buy the stock with a view to getting rid of the management. But still, good luck to them, they made a lot of money.”

True to character, Fox penny-pinched to the very end. Because the film’s final budget was $11,293,151, $3 million over the imposed budget—though fairly close to at least one of the early projected budgets—the studio had taken a part of Lucas’s directorial fee as compensation. “George was committed personally for $15,000 of his salary, as a penalty against the budget overage,” Kurtz says. “That was another thing that we argued and argued and argued about with them—and they didn’t reimburse him until after the movie came out.”

Of course by that time, Lucas’s financial situation was different from that of most filmmakers, even the most successful ones. His insistence, the help of his lawyers, and the ongoing fantastic success of the movie guaranteed him a fortune. Plus, as the film garnered what was evidently becoming a loyal fan base, its ancillary and sequel rights became more and more important. “George not only determined what products to go with, but achieved complete creative control on how the artwork looks, how the packaging looks, what ads would be used,” Jake Bloom says. “Whereas I firmly believe, under the traditional Hollywood deals that were made prior to this picture, that George would not have had creative control over these deals.”

One area where Lucas capitalized on this creative control was in his deal with Marvel Comics—negotiated by Lippincott—for a full-color serial adaptation. The fact that it was written by Roy Thomas and penciled by Howard Chaykin, both of whom had sizable reputations and followings, gave the film a legitimacy in certain circles. “Studios minimized the comic fan,” Bloom explains, “but George felt they were important in creating a base of hard-core fandom. It’s a word-of-mouth business. That’s something that Twentieth Century-Fox did not see three and a half years ago, but George saw it. Because of that Twentieth and George are now receiving vast benefits. I’m sure the studio will look at their contract and suddenly say, ‘How could we have made that deal? How could we do that?’ But they should thank God that they did it. They fell into something that they couldn’t even envision.”

Artwork by Charles White III and Drew Struzan was featured in the summer 1978 re-release poster, which ran in newspapers across the country, including the July 16, 1978, edition of the Los Angeles Times (elongated to include credits).

“Yesterday [August 10, 1977], I was out at Fox, and I was talking to the business affairs people,” Tom Pollock says. “And they told me that there are seven different stories circulating about why those rights were given to George—when they had never been given to anybody else before, have never been given to anybody else since, and will never be given to anyone in the future. They said there are seven stories about why they gave away the sequel rights. Because the sequel rights are enormously valuable. And they gave us half the merchandising. It was George’s idea and I give it all to George.”

“Recently [summer of 1977], I went to the latest comic convention in San Diego after the picture’s success,” Bloom adds. “Star Wars was probably the major thing down there; suddenly people are merchandising and trading and starting to collect Star Wars items. We already have avid collectors who will be there forever.”

“The first screening of the completed film was at the big theater on the lot at Fox the Friday before it opened,” Lippincott says. “It was a daytime screening for the Variety critic who blew his top because I invited 20 people from the sci-fi and comic book world who had helped me out. The critic gave us a very good review and it turned out my guests over the weekend called many of their friends around the country. The spark really took off and affirmed what many had hoped about the film.”

Lucas, as well as John Williams, also struck gold when the soundtrack, which sold for about $9, went platinum with 650,000 copies selling by mid-July. The stock of General Mills, which owned Kenner, went up dramatically, too—solely based on the rumor that it would procure the toy license for the film—which it did (though toys didn’t hit the market until after the holiday season of 1977). With all of his success, Lucas decided to give points or percentages of points as gifts. “Everybody has points, but the key is to make them pay off,” Lucas says. “I had a chance to give away a lot of my points, which I had done with Graffiti. The actors, composer, and crew should share in the rewards.”

Among those he gave a part of the profits to were: Gary Kurtz; Willard and Gloria Huyck; the law firm of Pollock, Rigrod, and Bloom; actors Alec Guinness, Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill, and Harrison Ford; and Ben Burtt, Fred Roos, and John Williams.

As one might expect, news about a sequel spread rapidly—which led to a dramatic reversal of roles at Fox’s negotiating table. “My understanding is that when George’s agent came back for Star Wars two, he said, ‘Okay, one: The profit split is being reversed,’ ” Warren Hellman recalls. “ ‘Two: You’re going to donate the product rights to us. And three: You’re still not getting any sequel rights.’ This I do remember: There was a great board meeting where management said, ‘We have to give George the rights to his characters.’ But we had a bunch of lawyers who said, ‘You can’t simply give away property rights!’ We voted, and I think it was a six to five vote, because somebody had made the point that you can’t own his children.”

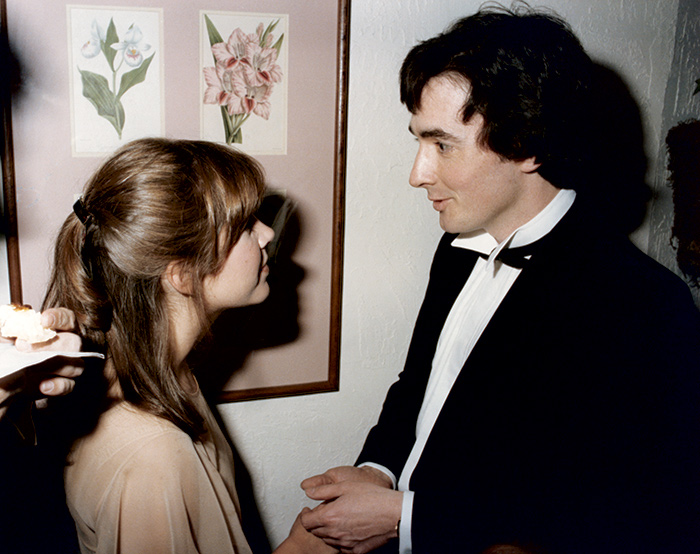

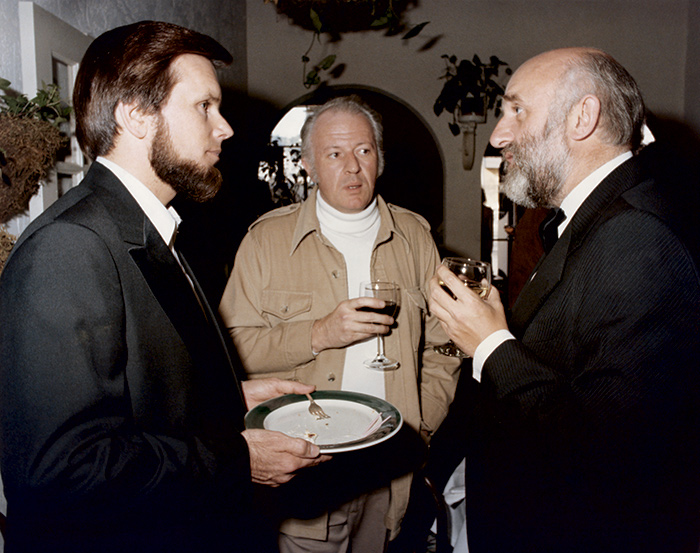

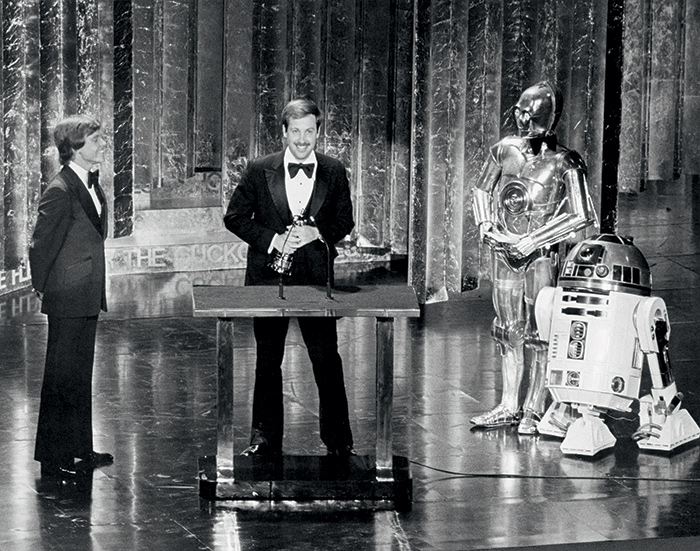

Festivities included the 1978 Oscars and other parties: Grant McCune, Mark Hamill, and Richard Chew, with others.

Carrie Fisher and Anthony Daniels

Gary Kurtz, Ralph McQuarrie, and John Barry

Eating dinner at the Academy Awards with their respective guests, Ben Burtt, Paul Hirsch, and Richard Chew.

Lucas chats with others at a party.

Flanked by C-3PO and R2-D2, Ben Burtt receives a Special Achievement Award for Best Sound Effects.

John Williams (with unidentified winner on left) with his Oscar for Best Original Score. Other recipients were John Barry, Norman Reynolds, Leslie Dilley, and Roger Christian for Best Art Direction/Set Decoration; John Stears, John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, Grant McCune, and Robbie Blalack for Best Special Effects; Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas, and Richard Chew for Best Editing; Don MacDougall, Ray West, Bob Minkler, and Derek Ball for Best Sound. Nominations included George Lucas for Best Director and Best Screenplay; Gary Kurtz for Best Picture; and Alec Guinness for Best Supporting Actor.

The inevitable slate of imitations was quickly planned by other studios, as well. Walt Disney productions began work on two films: Space Station One with a $10 million budget, targeted for teens, and The Cat from Outer Space, for younger kids. Universal and Paramount joined forces to plan a new version of When Worlds Collide. Universal began a remake of The Thing. The Doug Trumbull–run special effects house Future General was inundated with work, as were other specialty houses as studios wanted to jump-start any science-fiction film that they had stowed away on their shelves. To this day, Leonard Nimoy credits Star Wars with getting the first Star Trek film made, while, back in 1977, a new Star Trek TV series was announced at a fan convention in Los Angeles.

“It won’t be here forever,” says Greg Myers, who accompanied his eight-year-old daughter and two nephews to the cinema. “I thought I’d better see it [again] while I had the chance.”

“I’ve been hearing about this flick since it opened and I had to see it for myself,” Robbit Kitsch of Port Huron, Michigan, says. “I think I’m going to come back with a few friends and guide ’em through and enjoy it all over again.”

Indeed, repeat customers were another key to Star Wars’ first-run box-office longevity. Not only was it good, but tens of thousands of people also felt it warranted at least one more viewing—with some attending more than fifty shows—and, before the advent of consumer videos, people had only one place to see it. Thus, by September 13, in Bend, Oregon, an estimated 50 percent of each audience was repeat viewers.

Even with the film’s popularity assured, Twentieth Century-Fox’s terms—a guaranteed 12-week run, 90 percent of the profits after overhead, and a guaranteed $65,000 against earnings—kept profit margins thin for theater owners, though no doubt the studio expected them to pad their overhead. The studio also benefited from a U.S. Justice Department ruling in April 1977 that required theater owners to bid for films. Until then movie theatres in the same area would make “split agree-ments” in which they would join together to divide up the season’s first-run films—but that was ruled as being in violation of antitrust laws.

The winning bidder in Rocklander, New York, was the Town Theatre, where the film opened on August 5. With the percentage agreement, as reported by Jan Herman in the Journal-News, the theater had paid back the $65,000 guarantee by the third week. By the fourth week, the theater collected $16,000 for overhead and $9,300 profit—the rest of the $82,300 went to the studio. The second-month revenues of $66,400 provided a profit of $5,040 after overhead to the theater, with $45,360 going to Fox. Third-month profits dropped to $1,570 of $31,700 with the distributor getting $14,130.

By November 27, 1977, 90,000 people had attended Town Theatre’s 240 showings of Star Wars, that is, roughly one-third of the city’s population. Half of Benton County in Oregon—approximately 6,750 people—had seen it by July 29. The film ran for at least 18 weeks at the Cinema II theater in Danbury, Connecticut, where “phenomenal” repeat business was in evidence. In the tiny town of Hamilton, Texas, on November 10, Texan Theatre manager Lem Guthrie reported that Star Wars had entered its second week—which had never ever happened there before (one showing per night, $2 admission).

Across the nation, so many theaters were showing the film so often that new prints had to be made because the first were literally being worn out. Popcorn was sold like never before.

Nevertheless, Star Wars had to eventually move aside for new movies, such as Close Encounters. On October 20, the film was replaced by The Last Remake of Beau Geste after a record-setting 18-week run at Waterloo’s Strand Theatre in Cedar Falls, Iowa. It left Mentor, Ohio, on December 22, 1977, replaced by Neil Simon’s The Goodbye Girl.

Back in San Francisco in November, Fox and Columbia started bickering over which film would play the Coronet, Star Wars or Close Encounters of the Third Kind. “The Coronet has been established as the Star Wars theater in San Francisco,” Kurtz says. “It’s still doing $55,000 a week, which is amazing.” The Spielberg film went to the Northpoint. In Denver, Colorado, a press conference was convened in mid-December where it was announced that, to avoid problems, Star Wars would move from the Cooper to the Continental Theatre to make way for Close Encounters.

Star Wars has probably generated at least one critic for every hundred fans. Lucas himself joked, when he received the American Film Institute Life Achievement Award in 2005, that he was the “King of Wooden Dialogue.” Many consider him only a master of special effects, now known as visual effects (special effects referring in contemporary vernacular to those created on the sets, mainly pyrotechnics). But the fact remains that while Lucas was amazed that no one had done a film like Star Wars before him, only a few have done one since. And that’s because, as the story of the film’s creation shows, it’s nowhere near as simple as it might look to the casual observer.

Moreover, what comes out in several interviews is that the actual techniques used by ILM were not completely groundbreaking, or all that effective. Before the Dykstraflex was the Trumbullflex; Dennis Muren thinks they could’ve done better; Lucas certainly found the effects disappointing; and at the film’s release several experts didn’t find anything revolutionary in it at that level.

One only has to look at Disney’s The Black Hole (formerly Space Station One) to see that if effects and funny robots were the key, then there would be hundreds of Star Wars. That 1979 film, which also had beautiful matte paintings by Harrison Ellenshaw, is in fact the film Twentieth Century-Fox was afraid they were getting from Lucas: robots with eyes painted on them, cardboard characters, slight themes, and corny special effects. The Black Hole is not that bad a movie—particularly the end montage of hell—but in its attempts to copy Star Wars, right down to the opening shot, Lucas’s uniqueness of vision becomes clear by contrast.

Joe Johnston was impressed at the time by Lucas’s exactness: In each ship’s pan, rotation, and bank, there was an incredible eye at work. For what was reviewed as mainstream simplified cinema was actually an amalgam of abstract and cinema verité filmmaking with aspects taken from the work of directors such as Michael Curtiz and John Ford—all enhanced by Lucas’s editorial artistry. And for every piece of wooden dialogue, there is solid plotting underneath to support the characters and the themes he is developing.

“THX and Luke are both Buck Rogers,” Lucas says. “One is Buck Rogers today and the other is Buck Rogers in fantasy. One is the fantasy and one is the reality. Just two sides of the same coin. It’s the same heroism defined in different terms—but they start from the same spot: accepting responsibility for one’s actions. That’s the one thing I think that ties them together, and which ties them to American Graffiti. In a way all three of my movies have been about the same theme. THX 1138 looked at it from the point of view of a twenty-year-old. American Graffiti moved the perspective back to that of a sixteen-year-old. And now Star Wars tells the story from a twelve-year-old’s point of view.

“It was something I saw in high school and junior college, and it was clearest to me when I was in film school,” he explains. “I made seven movies in film school while everybody else was complaining that they couldn’t make movies because they didn’t have cameras, that they didn’t have film. Well, those people are still stuck. They didn’t realize that all you have to do is just do it.”

While sharing their major theme, Star Wars develops what is only hinted at in Lucas’s first two features: a more tangible mystical side, a return to the spiritual and perhaps more real self. The arrival of the droids on Tatooine and their purchase by Uncle Owen starts Luke Skywalker on an adventure toward his highest dreams of himself, some of which are thrust upon him and some of which he creates. Where he is drifting in the beginning, he is awakened by the end. As is Han Solo, although his transition is often overlooked—but he, too, goes from an ambiguous materialism to an acceptance of responsibility. It’s not an accident that Lucas dressed them similarly for the end ceremony.

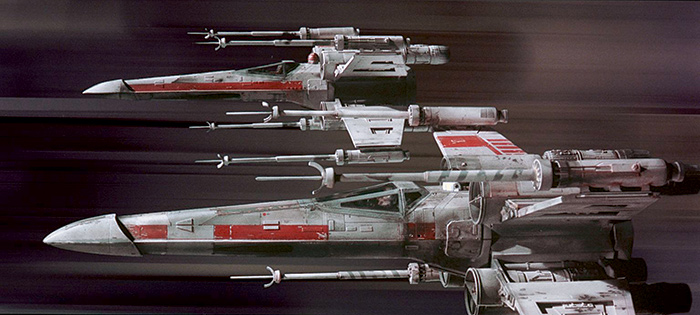

Final frames capture the speed that Lucas wanted during the final attack on the Death Star, though a few ILMers initially took issue with its departure from reality.

Psychologically speaking, Luke has to rid himself of his surrogate fathers—Uncle Owen, Darth Vader, and even Obi-Wan—before he can be truly independent. In this sense he also stands with Curt of Graffiti, and THX—all three are independent at the end of their films and looking out on the future: Curt from an airplane window, THX at the sun, and Luke from the podium. While Lucas would go on to add many shades of gray to the future saga, Star Wars is really the third chapter in the trilogy of his youth. THX is the almost passive rebel who leaves a mindless society behind; Curt is a less passive loner who leaves a small town behind; and Luke is the future and mystical knight-king who leaves his farm behind—but gains a new family in Solo, Leia, Chewbacca, and the droids. Not to mention the Rebel Alliance. He is happily in the world.

“Making a movie is very much like constructing a house,” Lucas says. “No matter how you plan it, there are adjustments that have to be made along the way, because nobody can envision the finished structure. But that’s essentially what filmmaking tries to do, and of course life gets involved in it when you are shooting. Personalities, weather, nature—everything comes into it and adjusts it. As you bring it to life, and the film becomes a real thing, you see it in a different way.

“So I ran the race and I didn’t do as good as I should have by a long shot,” he adds. “But whether I won or lost, I still ran the race. I couldn’t have done it any better because I tried to do it as well as I possibly could. But I certainly fell far short of what I wanted. And nothing will change that. It’s really not a matter of being satisfied; I don’t think you are ever satisfied. But when I saw the first cut, my only opinion was that I did a terrible job, but it works. It doesn’t work very well, but it works. That was reconfirmed when I saw the trailer for the first time. I thought, This is the movie I set out to make. Spaceships flying around and monsters and craziness. And then when I finally saw it with an audience for the first time, I realized that no matter how far short I fell, and how far short all the departments fell from what I wanted, the film did work for an audience. I feel a movie is very binary: It either works or it doesn’t work. And it did work. The audience did relate to it. They all laughed at the right places and they believed it.”

Finally, in the summer and fall of 1977, Lucas took more time off and was able to reflect and relax. He attended a celebratory dinner with the board of directors at Fox, which was held on a sound stage where Lucas was seated next to Princess Grace’s daughter Caroline. He also sat down for more interviews with Lippincott, during which he talked about his future plans: “More than anything else, I am interested in seeing the genre of science-fiction adventure become strong, like the Western. I would like to see more high adventures in space. But I don’t want to be a slave of technology; I want to be able to have the technology available, and create whatever visions people can come up with. I would like to make it as free as the literary side of the genre, which is asking an awful lot.

“I think science fiction still has a tendency to make itself so pious and serious, which is what I tried to knock out in making Star Wars. Kubrick did the strongest thing in film in terms of the rational side of things, and I’ve tried to do the most in the irrational side of things because I think we need it. I would feel very good if someday they colonize Mars, when I am ninety-three years old or whatever, and the leader of the first colony says: ‘I really did it because I was hoping there would be a Wookiee up here.’ ”

To the press, Lucas stated several times that he was going to retire from directing. Given the experience of the previous four years, he was exhausted. His friends and colleagues were not surprised, as they’d observed his difficulties firsthand. They were also confident that he would remain fundamentally the same. “I don’t think you’ll see any change,” Harrison Ford says. “I don’t see any change in George after his success.”

In USC’s student paper, the Daily Trojan, on December 9, 1977, staff writer Rori Benka reported on a visit Lucas made to his alma mater. While the public was still standing in lines to see Star Wars, Lucas reiterated in a closed-door presentation how disappointed he was in his film. When asked about his future, he responded, “I’m retired now, I’ve done it. I have let a lot of distractions into my life, on purpose, because I want to enjoy some things that I’ve never been able to enjoy before. I can enjoy the success of the film, a nice office to work in, and restoring my house, going on vacations. I’ve decided to set a year or so aside to enjoy those distractions. Plus, I’m setting up a company and getting the sequels off on the right track.”

To create the special effects for the two sequels, Lucas would again employ Industrial Light & Magic—but this time it would be closer to home, as he’d originally envisioned. So those first employees had a choice: They could either stay in Southern California or move north to San Rafael.

At USC circa December 7, 1977, are: (front row) Lucas, Howard Kazanjian (who would become a producer for Lucas), Carol Kazanjian, Charles Lippincott, the late Dave Johnson (a USC cinema instructor); (second row) Randal Kleiser (filmmaker and former roommate of Lucas’s), John Milius, (unknown), Willard Huyck, Bunny Alsup; (third row) Jake Bloom, Tom Pollock, and Matthew Robbins. Lucas, Kazanjian, Lippincott, Kleiser, Milius, Huyck, and Rob-bins had all been students at USC’s School of Cinema.

The ILMers who stayed in the Van Nuys facility changed their name to Apogee. That group included Bob Shepherd, John Dykstra, Richard Alexander, Alvah Miller, Grant McCune, Lorne Peterson, and Richard Edlund—though the latter two would rejoin ILM about a year later. Apogee intended to make a feature film, according to Shepherd, but that never happened. They did do the special effects for Caddyshack (1980) and Firefox (1982), among several others; the late-1970s TV show Battlestar Galactica; and many commercials.

One of those who moved north was Dennis Muren, who was eager to help Lucas advance the capabilities of special effects. “There’s no way at the moment that this equipment can do a stop-motion dinosaur,” Muren says. “If they eventually can do it, it’s going to be great, and we’ll be able to have some really neat-looking shots, but that’s a long way off.” Muren would eventually help bring those dinosaurs to life in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, in 1993, at ILM—winning him one of his seven Oscars.

“Of all the people who came here, Joe Johnston is certainly the one who is going to be known and heard from again,” Shepherd predicted. “He might art-direct an important movie …” Johnston would also make the move to San Rafael, remaining at ILM for a number of years before going off to direct films such as Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989); Jurassic Park III (2001); and Hidalgo (2004).

The list of accomplishments later achieved by those who worked on Star Wars would fill many pages, even if only measured by awards. Harrison Ford went on to embody Indiana Jones and become a gigantic star, winning the American Film Institute Life Achievement Award in 2000; John Williams continued to write music and win Oscars, most recently for Schindler’s List in 1994; Paul Hirsch would be nominated for an Academy Award for Ray (2004); John Mollo, after working on Alien, won for Gandhi in 1983; Rick Baker would win six Oscars; Ralph McQuarrie won an Academy Award for Cocoon (1986) as did Ken Ralston, who won five others; Ben Burtt received two Oscars, one for Spielberg’s E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982); John Dykstra received one for Spider-Man 2 in 2004; Alan Ladd Jr. won an Academy Award for Best Picture in 1996 for Braveheart; and of course Lucas was given what is perhaps the industry’s most coveted honor, the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, in 1992.

Sadly, John Barry died shortly after making Star Wars, while at work on the first of the sequels, on June 1, 1979. And Adam Beckett, who was by all accounts a brilliant animator, died tragically in a fire in 1978. Of course several other Star Wars veterans have since passed away.

As for the future of cinema, Lucas’s vision of a special effects palette that would allow filmmakers as much freedom of imagination as writers and painters coincided with Dykstra’s 1978 prediction: “The next step is digital, because then you can do anything you want.”

And while he wouldn’t direct again for two decades, Lucas dedicated years of his life and millions of his dollars in pursuit of that digital goal, helping in the process to create digital editing, sound, and cameras, as well as what has become Pixar Animation Studios.

“If one wants to know the future of the film industry, one goes up to San Francisco and visits George,” Martin Scorsese says. “It’s as simple as that.”

“I’m interested in cinema, the psychological process, why certain films work and others

don’t. Film is magic. That’s all it is. You’re sitting there with one hand doing one thing, while you’re

fooling the audience with the other hand.”

—George Lucas

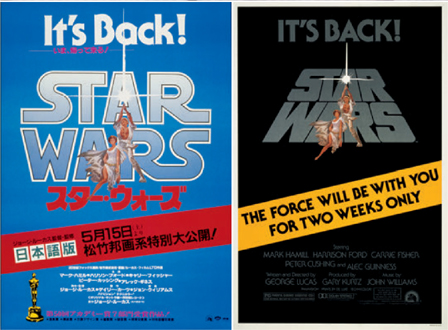

In 1979 a Japanese poster touted Star Wars’ Oscars and a sneak preview of The Empire Strikes Back, the first sequel (left); in 1981 a U.S. poster (right) signals another revival—one of many that would continue unabated for decades …